Sieges, Part 6, Cities, Forts and Big Guns

Siege of Paris, 1870-1871

The Siege of Paris, lasting from 19 September 1870 to 28 January 1871, and the consequent capture of the city by Prussian forces, led to French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War and the establishment of the German Empire as well as the Paris Commune.

The Siege of Paris, 1870-1871, painting by Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier.

As early as August 1870, the Prussian 3rd Army led by Crown Prince Frederick of Prussia (the future Emperor Frederick III), had been marching towards Paris. The army was recalled to deal with French forces accompanied by Napoleon III. These forces were crushed at the Battle of Sedan, and the road to Paris was left open. Personally leading the Prussian forces, King William I of Prussia, along with his chief of staff Helmuth von Moltke, took the 3rd Army and the new Prussian Army of the Meuse under Crown Prince Albert of Saxony, and marched on Paris virtually unopposed. In Paris, the Governor and commander-in-chief of the city’s defenses, General Louis Jules Trochu, assembled a force of 60,000 regular soldiers who had managed to escape from Sedan under Joseph Vinoy or who were gathered from depot troops. Together with 90,000 Mobiles(Territorials), a brigade of 13,000 naval seamen and 350,000 National Guards, the potential defenders of Paris totalled around 513,000 personnel. The compulsorily enrolled National Guards were, however, untrained.

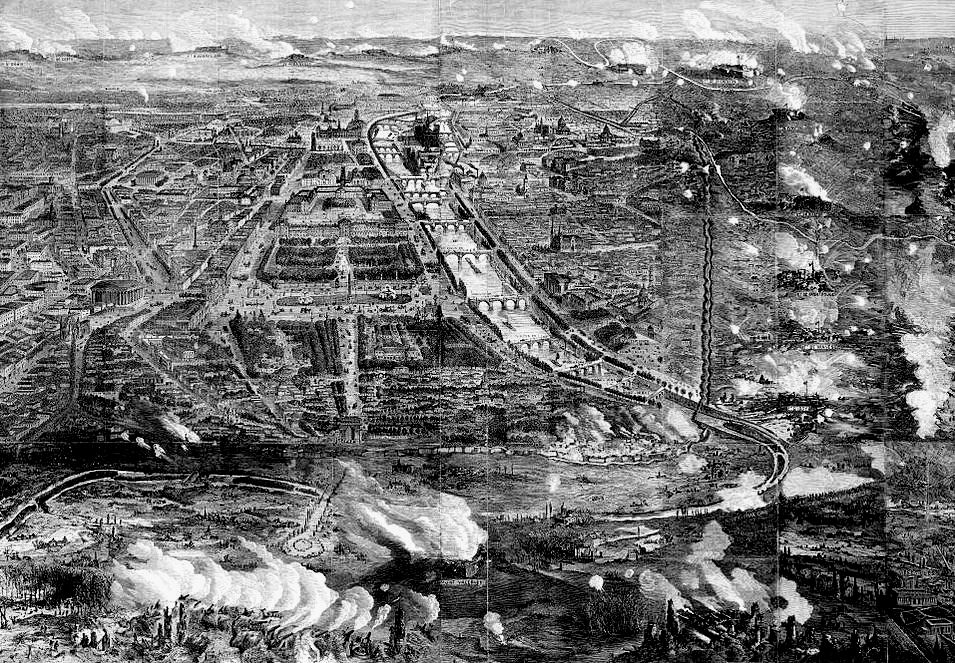

The Prussian armies quickly reached Paris, and on 15 September Moltke issued orders for the investment of the city. Crown Prince Albert’s army closed in on Paris from the north unopposed, while Crown Prince Frederick moved in from the south. On 17 September a force under Vinoy attacked Frederick’s army near Villeneuve-Saint-Georges in an effort to save a supply depot there, but it was eventually driven back by artillery fire. The railroad to Orleans was cut, and on the 18th Versailles was taken, and then served as the 3rd Army’s and eventually Wilhelm’s headquarters. By 19 September the encirclement was complete, and the siege officially began. Responsible for the direction of the siege was General (later Field Marshal) von Blumenthal.

Prussia’s chancellor Otto von Bismarck suggested shelling Paris to ensure the city’s quick surrender and render all French efforts to free the city pointless, but the German high command, headed by the king of Prussia, turned down the proposal on the insistence of General von Blumenthal, on the grounds that a bombardment would affect civilians, violate the rules of engagement, and turn the opinion of third parties against the Germans, without speeding up the final victory. It was also contended that a quick French surrender would leave the new French armies undefeated and allow France to renew the war shortly after. The new French armies would have to be annihilated first, and Paris would have to be starved into surrender.

Trochu had little faith in the ability of the National Guards, which made up half the force defending the city. So instead of making any significant attempt to prevent the investment by the Germans, Trochu hoped that Moltke would attempt to take the city by storm, and the French could then rely on the city’s defenses. These consisted of the 33 km (21 mi) Thiers wall and a ring of 16 detached forts, all of which had been built in the 1840s. Von Moltke never had any intention of attacking the city and this became clear shortly after the siege began. Trochu changed his plan and allowed Vinoy to make a demonstration against the Prussians west of the Seine. On 30 September Vinoy attacked Chevilly with 20,000 soldiers and was soundly repulsed by the 3rd Army. Then on 13 October the II Bavarian Corps was driven from Châtillon but the French were forced to retire in face of Prussian artillery.

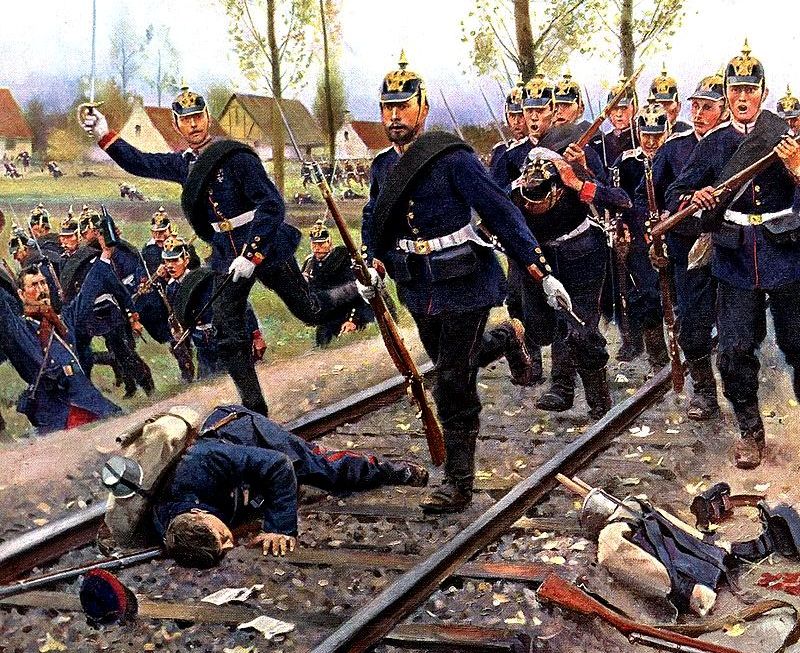

Kompagnie des Kaiser-Alexander-Garde-Grenadier-Regiments Nr. 1 attacking near Le Bourget,on 30 Oct 1870, painting by von Carl Röchling.

General Carey de Bellemare commanded the strongest fortress north of Paris at Saint Denis. On 29 October de Bellemare attacked the Prussian Guard at Le Bourget without orders, and took the town. The Guard actually had little interest in recapturing their positions at Le Bourget, but Crown Prince Albert ordered the city retaken anyway. In the battle of Le Bourget the Prussian Guards succeeded in retaking the city and captured 1,200 French soldiers. Upon hearing of the French surrender at Metz and the defeat at Le Bourget, morale in Paris began to sink. The people of Paris were beginning to suffer from the effects of the German blockade. Hoping to boost morale Trochu launched the largest attack from Paris on November 30 even though he had little hope of achieving a breakthrough. Nevertheless, he sent Auguste-Alexandre Ducrot with 80,000 soldiers against the Prussians at Champigny, Créteil and Villiers. In what became known as the battle of Villiers the French succeeded in capturing and holding a position at Créteil and Champigny. By 2 December the Württember Corps had driven Ducrot back into the defenses and the battle was over by 3 December.

On 19 January a final breakout attempt was aimed at the Château of Buzenval in Rueil-Malmaison near the Prussian Headquarters, west of Paris. The Crown Prince easily repulsed the attack inflicting over 4,000 casualties while suffering just over 600. Trochu resigned as governor and left General Joseph Vinoy with 146,000 defenders.

During the winter, tensions began to arise in the Prussian high command. Field-Marshal Helmuth von Moltke and General Leonhard, Count von Blumenthal who commanded the siege, were primarily concerned with a methodical siege that would destroy the detached forts around the city and slowly strangle the defending forces with a minimum of German casualties.

But as time wore on, there was growing concern that a prolonged war was placing too much strain on the German economy and that an extended siege would convince the French Government of National Defence that Prussia could still be beaten. A prolonged campaign would also allow France time to reconstitute a new army and convince neutral powers to enter the war against Prussia. To Bismarck, Paris was the key to breaking the power of the intransigent republican leaders of France, ending the war in a timely manner, and securing peace terms favourable to Prussia. Von Moltke was also worried that insufficient winter supplies were reaching the German armies investing the city, as diseases such as tuberculosis were breaking out amongst the besieging soldiers. In addition, the siege operations competed with the demands of the ongoing Loire Campaign against the remaining French field armies.

(Braquehais, Bruno)

French gunners during the siege of Paris, 1870.

(Harper & Brothers)

Pictorial map of the city of Paris and its environs during the siege, 1870.

On 5 January, on Bismarck’s advice, the Germans fired some 12,000 shells into the city over 23 nights in an attempt to break Parisian morale. About 400 perished or were wounded by the bombardment which, “had little effect on the spirit of resistance in Paris.” Due to a severe shortage of food, Parisians were forced to slaughter whatever animals were at hand. Rats, dogs, cats and horses were the first to be slaughtered and became regular fare on restaurant menus. Once the supply of those animals ran low, the citizens of Paris turned on the zoo animals residing at Jardin des plantes. Castor and Polux, the only pair of elephants in Paris, were slaughtered for their meat.

On 25 January 1871, Wilhelm I overruled von Moltke and ordered the field-marshal to consult with Bismarck for all future operations. Bismarck immediately ordered the city to be bombarded with large-caliber Krupp siege guns. This prompted the city’s surrender on 28 January 1871. Paris sustained more damage in the 1870–1871 siege than in any other conflict.

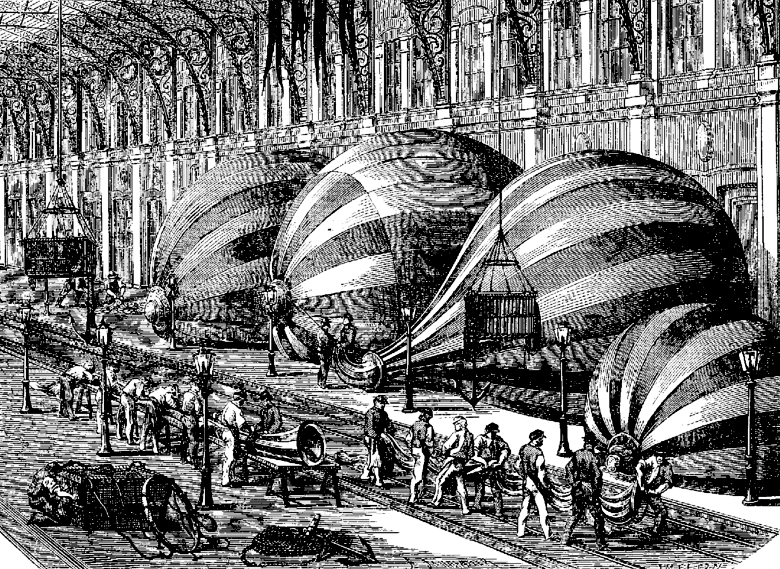

Balloon mail was the only means by which communications from the besieged city could reach the rest of France. The use of balloons to carry mail was first proposed by the photographer and balloonist Felix Nadar, who had established the grandiosely titled No. 1 Compagnie des Aérostatiers, with a single balloon, the Neptune, at its disposal, to perform tethered ascents for observation purposes. However the Prussian encirclement of the city made this pointless, and on 17 September Nadar wrote to the Council for the Defence of Paris proposing the use of balloons for communication with the outside world: a similar proposal had also been made by the balloonist Eugene Godard.

Construction of balloons at the Gare d’Orleans, 1870, engraving by Louis Figuier.

The first balloon launch was carried out on 23 September, using the Neptune, and carried 125 kg (276 lb) of mail in addition to the pilot. After a three-hour flight it landed at Craconville, 83 km (52 mi) from Paris. Following this success a regular mail service was established, with a rate of 20 centimes per letter. Two workshops to manufacture balloons were set up, one under the direction of Nadar in the Elys?e-Montmartre dance-hall (later moved to the Gare du Nord and the other under the direction of Godard in the Gare d’Orleans. Around 66 balloon flights were made, including one that accidentally set a world distance record by ending up in Norway. The vast majority of these succeeded: only five were captured by the Prussians, and three went missing, presumably coming down in the Atlantic or Irish Sea. The number of letters carried has been estimated at around 2.5 million. Some balloons also carried passengers in addition to the cargo of mail, most notably Leon Gambetta, the minister for War in the new government, who was flown out of Paris on 7 October. The balloons also carried homing pigeons out of Paris to be used for a pideon post. This was the only means by which communications from the rest of France could reach the besieged city. A specially laid telegraph cable on the bed of the Seine had been discovered and cut by the Prussians on 27 September. Couriers attempting to make their way through the German lines were almost all intercepted and although other methods were tried including attempts to use balloons, dogs and message canisters floated down the Seine, these were all unsuccessful.

The departure from Paris of Leon Gambetta on the balloon l'”Armand-Barbès” on 7 Oct 1870, painting by Jules Didier and Jacques Guiaud.

The French defeat was followed by a popular uprising and the establishment, in March 1871, of the Paris Commune, a revolutionary government formed in accordance with anarchist and socialist principles. The Commune was bloodily suppressed in May 1871 by French troops under the government of Adolphe Thiers. During the brief period in which the communards controlled Paris, they dismantled the imperial column in the Place Vendôme. The suppression of the Commune resulted in further extensive damage to the city, as the communards set fire to the Tuileries Palace, the Louvre, and other buildings, and as desperate fighting between the communards and counterrevolutionary forces destroyed or damaged many other structures.

Battle of Rorkes Drift, 1879

The South African landscape has seen more than its share of battles and sieges. On 22 January 1879, the Battle of Rorkes Drift was fought during the Zulu-British War. Chief Cetewayo with more than 4,000 Zulus attacked northern Natal. Lt John Chard of the Royal Engineers with 140 troops fought off Cetewayo’s tribesmen killing 400 and taking 25 casualties of his own. As a result, eleven Victoria Crosses were awarded, more than for any other single action ever fought.[259]

Painting by Alphonse de Neuville of the Battle of Rorke’s Drift which took place in Natal during the Anglo-Zulu War in 1879.

Siege of Mafeking, 1899

Firepower alone however, was rarely sufficient to protect or defeat a fortress. During the Boer War in 1899-1902 both sides brought heavy long-range artillery into the field. The British eventually won the war by carrying out punitive expeditions based on chains of blockhouses, although the firepower of modern arms enabled the Boers to resist for two and a half years.[260]

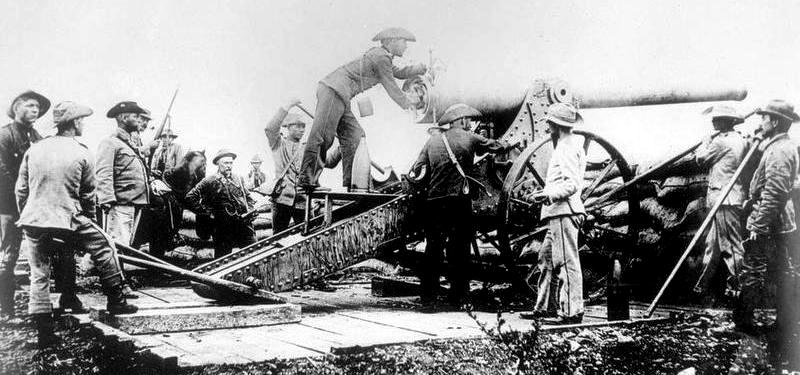

General Piet Cronje’s 94-pounder Creusot “Long Tom” gun, in service during the siege of Mafeking, South Africa, in 1899.

General Piet Cronje’s 94-pounder Creusot“Long Tom” gun firing on the British forces during the siege of Mafeking, South Africa, in 1899.

In 1899, the town of Mafeking in South Africa held by British forces came under siege by the Boer army.[261] Mafeking is situated upon the long line of railway, which connected Kimberley in the south with what was then known as Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) in the north. It served as the main depot for the western Transvaal on one side, and the starting-point for all attempts to cross upon the Kalahari Desert on the other, with the Transvaal border sited within a few miles of it. It was not clear to the defenders why the town should have been held since it had no natural advantages to aid in its defense, and lay exposed in a widespread plain. Looking at a map, an attacker would quickly determine that the rail lines could easily be cut in places both north and south of the town, and the garrison was isolated some 250 miles from any reinforcements. The Boers clearly had the strength in men and guns to seize the town if and when they chose to do so. The unanticipated variable would be the extraordinary tenacity and resourcefulness of the defending commander, Colonel Baden-Powell. “Through his exertions the town served as a bait to the Boers, and occupied a considerable force in a useless siege at a time when their presence at other seats of war might have proved disastrous to the British cause.”

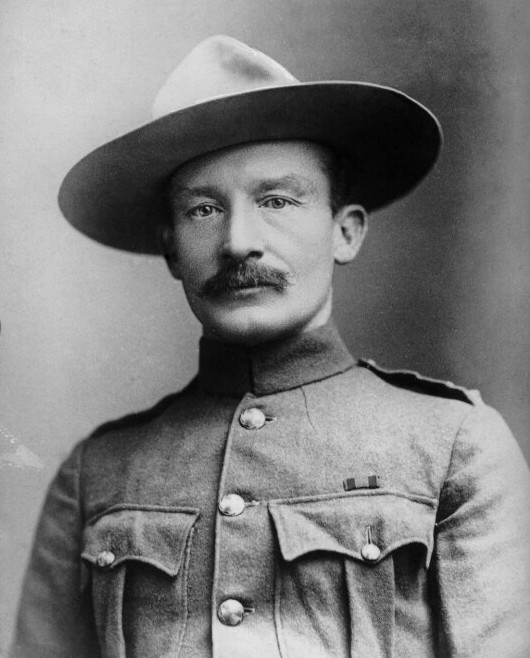

LCol Robert S.S. Baden-Powell, South Africa, 1896.

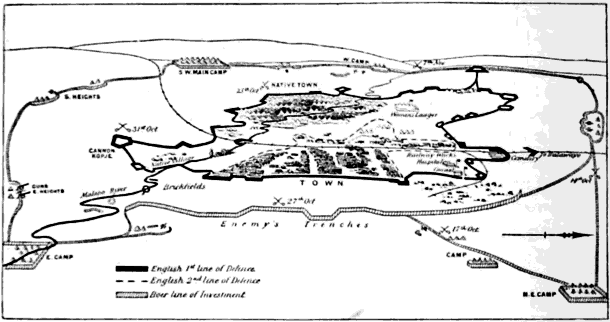

The Siege of Mafeking. Topographical Sketch showing the British and Boer Positions. From a sketch by a British officer brought by runner to Buluwayo.

(The Graphic, Photo)

Boer riflemen at Makefing.

Colonel Baden-Powell was the kind of soldier who was exceedingly popular with the British public. A skilled hunter and an expert at many games, there was always something of the sportsman in his keen appreciation of war. In the Matabele campaign he had out-scouted the opposition’s scouts and enjoyed himself tracking them through their native mountains, often alone and at night, trusting to his skill to save him from their pursuit. He would prove to be as difficult to outwit, as it was to outfight him. He was also blessed with a curious sense of humor, meeting the Boers head on with bluffs and jokes which were as disconcerting to them as his wire entanglements and his rifle-pits. It has also been said that he had that “magnetic quality by which the leader imparts something of his virtues to his men.”

Even before the formal declaration of war, Baden-Powell had been well aware of the precarious state of defenses at Mafeking and had taken steps to prepare for the worst by provisioning the town. The garrison of the town consisted of irregular troops, 340 of the Protectorate Regiment, 170 Police, and 200 volunteers, as well as the Town Guard, who included the able-bodied shopkeepers, businessmen, and residents, numbering 900 men. Their artillery consisted of just two 7-pounder guns and six machine guns. Under the able direction of Colonel Vyvyan and Major Panzera who planned the defenses, Mafeking soon began to take on the appearance of a fortress.

The Boers arrived on 13 October, and were met by two truckloads of dynamite sent out by Baden-Powell. The attackers fired on them blowing them to pieces. By 14 October, British pickets, which had been sited around the town, were driven behind their defenses. As they began their withdrawal, the defenders sent out an armoured train and a squadron of a unit known as the “Protectorate Regiment,” to support the pickets and drove the Boers way from them. A few of the Boers later doubled back and interposed themselves between the British and Mafeking. In response, two fresh troops were sent out from the garrison equipped with a 7-pounder cannon which was used to effectively fire enough high-explosive shrapnel to drive them off. The garrison lost two killed and fourteen wounded, but they inflicted considerable damage on the Boers.

On 16 October the Boers stepped up their siege efforts, and brought two 12-pounder guns to bear on Mafeking. They also managed to seize the garrison’s outside water supply, although in anticipation of this, the garrison had already dug wells. Before 20 October, 5,000 Boers, under their formidable leader, General Cronje, had surrounded the town. He sent the garrison a message, which read, “Surrender to avoid bloodshed.” In response, Baden-Powell asked, “When is the bloodshed going to begin?” After the Boers had been shelling the town for some weeks the light-hearted Colonel sent out another message telling Cronje, “if the shelling went on any longer he should be compelled to regard it as equivalent to a declaration of war.” (Cronje’s reply has not been reported).

The town’s defenses contained some major drawbacks. For one, there were only about 1,000 men to defend a protective wall of five or six miles in circumference against a determined attacker who could assault at any point and time at his convenience. To cope with this, the defenders devised an ingenious system of small forts, each of which held from ten to forty riflemen, protected with bomb-proof shelters and covered ways. The central bomb-proof shelter was connected by a telephone line, which ran out to all the outlying forts, which reduced the risk and manpower in the form of runners. An alarm system was rigged using a system of bells within each quarter of the town. These were rung when an incoming shell was observed in time to enable the inhabitants to get to shelter. The defenders also made use of an armoured train, which they camouflaged with green paint, covered it with scrub, and kept hidden in the clumps of bushes which surrounded the town.

The Boers began a heavy bombardment of the town on 20 October, and kept it up with brief intervals for seven months. The Boers had brought an enormous gun across from Pretoria, which fired a 96-pound shell, and this, with many smaller pieces, kept up a nearly continuous fire on the town, although little was achieved. As the Mafeking guns were too weak to adequately return the Boer fire, Colonel Baden-Powell determined that a more suitable response would be to conduct a fighting patrol or sortie. On the evening of 27 October, about 100 men under Captain FitzClarence moved out against the Boer trenches with instructions to use only their bayonets. The mission was successful and the Boer position was overrun with many of the Boers being bayoneted before they could disengage themselves from the tarpaulins, which covered them. The British lost six killed, eleven wounded, and two prisoners, with the Boer losses slightly higher.

On 31 October, the Boers launched an attack on Cannon Kopje, a small fort and eminence to the south of the town defended by Colonel Walford, of the British South African Police, with 57 of his men and three small guns. The attack was repelled with heavy loss to the Boers. The British casualties were six killed and five wounded.

This experience seems to have caused the Boers to rethink their strategy, and no further expensive attempts were made to rush the town. For the next few weeks the siege degenerated into a blockade. About this time, Cronje was recalled to deal with a more important task, and the siege was taken over by Commandant Snyman. The Boers continued to use their great gun to fire its huge shells into the town, but the defenders boardwood walls and corrugated iron roofs reduced the impact of the bombardment. On 3 November the garrison sent out a sortie to storm a position called “the Brickfields,” which had been held by the enemy’s sharpshooters. Another small harassing sally ventured out on 7 November.

On 18 October, Colonel Baden-Powell sent a message to Commandant Snyman that he could not take the town by biting and looking at it. At the same time he dispatched a message to the Boer forces generally, advising them to return to their homes and their families. Some of the commandos had gone south to assist Cronje in his stand against Methuen, and the siege stagnated until 26 December when the garrison launched a casualty intensive sortie against the Boers. This attack was made against one of the Boer forts on the north. The Boers may have had some idea of what was coming, because the fort had been strengthened to the point where it could not be taken without the use of scaling ladders. The attacking force consisted of two squadrons from the Protectorate Regiment and one of the Bechuanaland Rifles, backed up by three guns. 53 out of the 80-man attacking force were killed and wounded, (25 killed, 28 wounded).

Such losses could not be sustained, and from then on, Colonel Baden-Powell chose to hold on until he could be relieved by the British forces under Plumer who could arrive from the north, or under Methuen who could drive up from the south. The siege settled down into a monotonous series of sporadic shelling by the Boers through the months of January and February. A truce was usually observed on Sunday, and the snipers who had exchanged rifle-shots all week gave only cat-calls and occasionally good-humored chaff. In spite of the humour, however, there was no neutral camp for women or sick, and the Boer guns kept up their fire against the inhabitants inside Mafeking in order to bring pressure upon the defenders to surrender.

In the midst of the siege, the defenders held a Jubilee ball, presided over by the Colonel, which was briefly interrupted by a Boer attack. The defenders also endeavored to keep up sports matches to maintain morale. (Apparently their Sunday cricket matches so shocked Snyman that he threatened to fire upon it if they were continued).

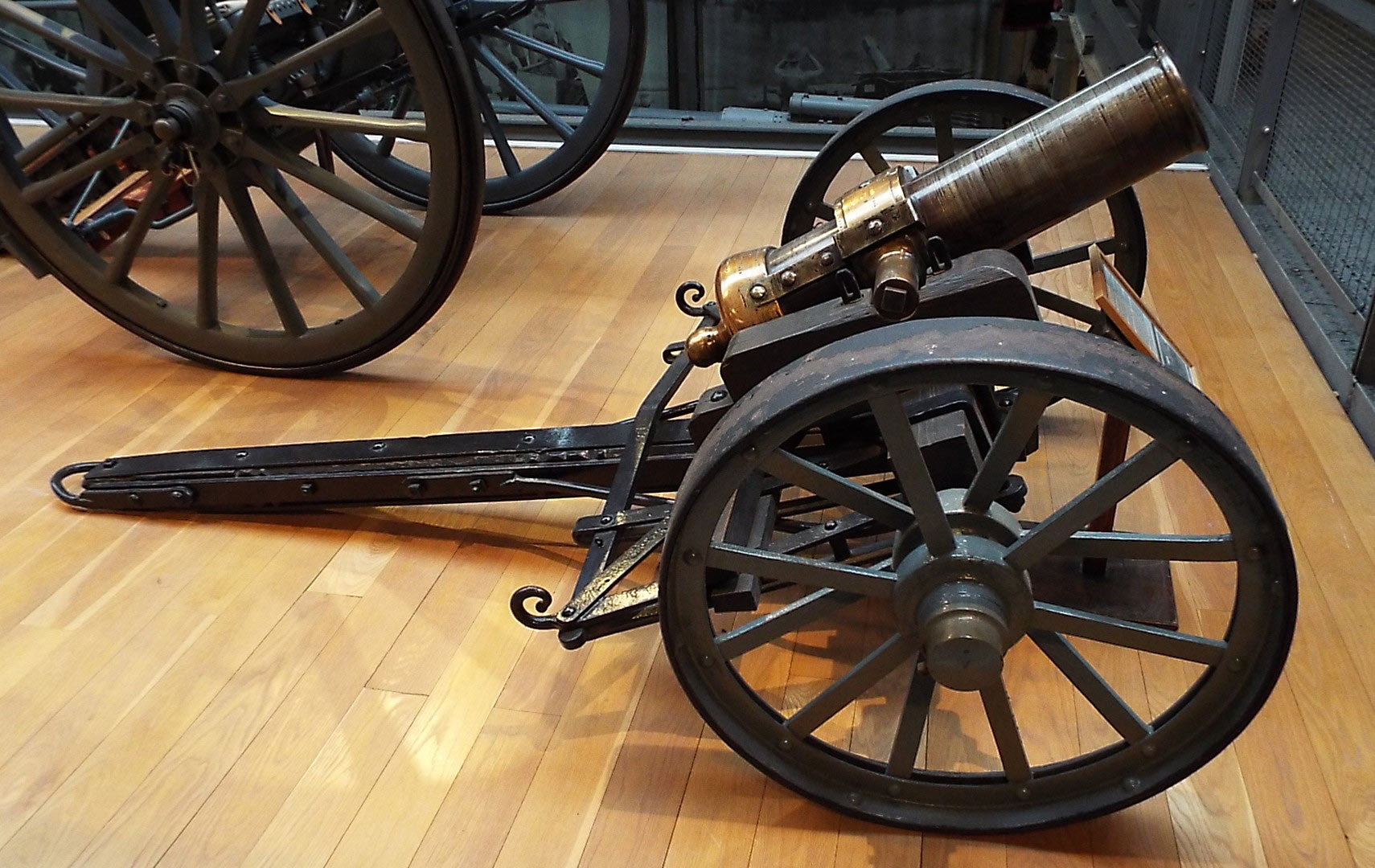

In spite of limited resources, an ordnance factory was put into operation in Mafeking, formed in the railway workshops, and conducted by two men named Connely and Cloughlan, of the Locomotive Department. Daniels, of the police, supplemented their efforts by making both powder and fuses. The factory turned out shells, and eventually constructed a 5.5-in. smooth-bore gun, which fired a round shell with great accuracy to a considerable range.

(Firepower Museum Photo)

British 5.5-inch Smoothbore “Wolf” Gun, built during the Siege of Mafeking.

The Boers constructed a series of trenches, which moved forward through the month of April 1900. When the trenches came within range, both sides resorted to throwing hand-grenades on each other, with a number being launched by Sergeant Page of the Protectorate Regiment. At times the numbers of the besiegers and their guns diminished, due to forces being detached to prevent the advance of Plumer’s relieving column from the north. The Boers who remained held their counter-forts, which the British defenders were unable to storm.

The northern British force had a difficult task fighting the Boers, but they were eventually strengthened by the relieving column, and began making their way to Mafeking. This force was originally raised for the purpose of defending Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), and it consisted of pioneers, farmers, and miners and other volunteers, many of whom were veterans of the native wars. The men of the northern and western Transvaal whom they were called upon to face, the burghers of Watersberg and Zoutpansberg, were tough frontiersmen living in a land where a “dinner was shot, not bought.” Sir Arthur Conan Doyle described them as “shaggy, hairy, half-savage men, handling a rifle as a medieval Englishman handled a bow, and skilled in every wile of veldt craft, they were as formidable opponents as the world could show.”

When the war first broke out, the British leadership in Rhodesia sought to save as much as possible of their railway line, which was kept them in contact with the south. For this reason, an armored train was dispatched just three days after the expiration of the Boer ultimatum to the British, to a point four hundred miles south of Bulawayo, where the frontiers of the Transvaal and of Bechuanaland join. Colonel Holdsworth commanded this small British force. About 1,000 Boer commandos attacked the train, but were driven back with a number being killed. The train then pressed on as far as Lobatsi, where it found the bridges destroyed. At this point the commander directed it to return to its original position. As it did so, it was attacked again by the Boer commandos, but escaped capture and destruction a second time. From then until the New Year the line was kept open by an effective system of patrolling to within a hundred miles or so of Mafeking. Skirmishes continued with a successful British attack on a Boer laager at Sekwani being carried out on 24 November. Colonel Holdsworth approached the Boer laager and attacked in the early morning with a force of 120 frontiersmen, killing or wounding a number of the Boers and scattering the rest. Other British forces were engaged in similar tactics elsewhere on the northern frontier.

About this time, Colonel Plumer had taken command of the small army, which was operating from the north along the railway line with Mafeking for its objective. Plumer was an officer with considerable experience in African warfare. Conan Doyle described him as, “a small, quiet, resolute man, with a knack of gently enforcing discipline upon the very rough material with which he had to deal.” With his weak force, which never exceeded a thousand men, and was usually from six to seven hundred, he had to keep the long line behind him open, build up the besieged railway in front of him and gradually creep onwards in face of a formidable and enterprising enemy. He kept his headquarters for some time at Gaberones, about 80 miles north of Mafeking, and kept up precarious communications with the besieged garrison. In the middle of March he advanced as far south as Lobatsi, which is less than fifty miles from Mafeking; but the Boers proved to be too strong for him, and Plumer had to drop back again with some loss to his original position at Gaberones.

Gathering his forces for another push, Plumer again came south, and this time made his way as far as Ramathlabama, within a day’s march of Mafeking. Unfortunately, he only had 350 men with him, which was not enough to press through to the garrison. Plumer’s relieving force was fiercely attacked by the Boers and driven back on to their camp with a loss of 12 killed, 26 wounded, and 14 missing. Although some of Plumer’s men were dismounted, he managed to extricate them safely while under attack by an aggressive mounted enemy. His force withdrew again to near Lobatsi, and collected itself for another effort.

While this was taking place, the defenders of Mafeking kept up a spirited and aggressive defense. Its riflemen maintained an accurate and deadly fire on the Boer gun crews, forcing them to move their biggest gun further away from the town. The siege had now dragged on for six months. In spite of being a small tin-roofed village, Mafeking had become a prize of victory, a symbol that would become a necessity for one side or the other to gain in order to demonstrate its supremacy in the South African conflict. Something had to be done to break the stalemate.

The Boer besiegers increased their ranks and added to the number of guns laying fire on Mafeking. On 12 May the Boer’s launched a dawn attack with about 300 volunteers under Commander Eloff. They had crept around to the west side of the town at a point furthest the lines of the besiegers. At the first rush they penetrated into the native quarter, which they immediately set on fire. The first large building they seized was the barracks of the Protectorate Regiment, which was held by Colonel Hore and about 20 of his officers and men. The Boers quickly sent an exultant message by telephone to Baden-Powell to tell him that they had it. The Boers held two other positions within the lines, one a stone kraal and the other a hill, but their reinforcements were slow in arriving, and they were immediately isolated by the defenders and cut off from their own lines.

The Boers had successfully penetrated the town but were still far from being able to take it. The British for their part spent the day squeezing a cordon around the Boer positions, hemming them in without rushing them and incurring casualties, but making it impossible for the Boer commandos to escape from them. Although a few burghers slipped away in twos and threes, the main body found itself trapped in a fire-sack swept with rifle fire. Recognizing the hopelessness of their position, at seven o’clock in the evening Eloff with 117 men laid down their arms. Their losses had been 10 killed and 19 wounded. It is not known why these men were not reinforced once they had gained entry, but if they had been, it is possible the attack would have been successful. Colonel Baden-Powell, with his characteristic sense of humor introduced himself to Commander Eloff, saying, “Good evening, Commandant, won’t you come in and have some dinner?” The prisoners, who were comprised of burghers, Hollanders, Germans, and Frenchmen, were apparently then treated to as good a supper as the destitute larders of the town could furnish.

Eloff’s attack was the last, though by no means the worst of the attacks, which the garrison had to face. The siege ended with the British having lost six killed and ten wounded. On 17 May 1900, five days after Eloff’s unsuccessful assault, the defenders of Mafeking were relieved. Colonel Mahon, a young Irish officer who had made his reputation as a cavalry leader in Egypt, had started early in May from Kimberley with a small but mobile force consisting of the Imperial Light Horse (brought in from Natal for the purpose), the Kimberley Mounted Corps, the Diamond Fields Horse, some Imperial Yeomanry, a detachment of the Cape Police, and 100 volunteers from the Fusilier brigade, with M battery horse artillery and pom-poms, some 1,200 men in all.

Mahon with his men struck round the western flank of the Boers and moved rapidly to the northwards. On 11 May, he had fought a short engagement with the Boers who had opened fire at short range on the Imperial Light Horse, who led the column. A short engagement ensued, in which the casualties amounted to 30 killed and wounded, but which ended in the defeat and dispersal of the Boers, whose force was certainly very much weaker than the British. On 15 May the relieving column arrived without further opposition at Masibi Stadt, twenty miles to the west of Mafeking.

In the meantime Plumer’s force in the north had been strengthened by the addition of C Battery of four 12-pounder guns of the Canadian Artillery under Major Eudon and a body of Queenslanders. These forces had been part of the small army which had come with General Carrington through Beira, and after a detour of thousands of miles, arrived in time to form a portion of the relieving column. These contingents had been assembled after taking long railway journeys, and then being conveyed across thousands of miles of ocean to Cape Town. From here they had covered enormous additional distances by rail and coach to Ootsi, and then conducted a 100-mile forced march to their battlefield positions. With these reinforcements and with his own hardy Rhodesians, Plumer pushed on and the two columns reached the hamlet of Masibi Stadt within an hour of each other. Their united strength was far superior to anything which Snyman’s force could place against them.

Although the Boers put up a stiff resistance, they were eventually forced to withdraw past Mafeking and took refuge in the trenches on the eastern side. At this point, Baden-Powell sallied out of the garrison, and, supported by the artillery fire from the relieving column, drove them from their shelter. The Boers still managed to escape with all of their guns except for one small cannon. They did leave a number of wagons and a considerable quantity of supplies.

The relieving force ended a siege of an open town which contained no regular soldiers and inadequate artillery against a numerous and enterprising enemy with very heavy guns. The defense of Mafeking took place during the opening months of the war, and held up a Boer force of between 4,000 and 5,000 commandos. If these forces had been available at other points in the British line, the losses might well have been unsustainable. The Boers kept 2,000 men and eight guns, (including one of the four big Creusots in their arsenal) on the siege lines. It prevented the invasion of Rhodesia, at a cost of 200 British lives, with Boers taking an estimated 1,000 casualties. In Arthur Conan Doyle’s words, “critics may say that the enthusiasm in the empire was excessive, but at least it was expended over worthy men and a fine deed of arms.”[262]

Liège, 1914

The Battle of Liège (Bataille de Liège) was the opening engagement of the German invasion of Belgium and the first battle of the First World War. The attack on Liège, a town protected by the Fortified position of Liège, a ring of fortresses built from the late 1880s to the early 1890s, began on 5 August 1914 and lasted until 16 August, when the last fort surrendered. The siege of Liège may have delayed the German invasion of France by 4–5 days. Railways in the Meuse river valley needed by the German armies in eastern Belgium were closed for the duration of the siege and German troops did not appear in strength before the Fortified Position of Namur at the confluence of the Sambre and Meuse rivers until 20 August.

Belgian military planning was based on an assumption that other powers would expel an invader. Belgian troops were to be massed in central Belgium, in front of the National redoubt of Belgium ready to face any border, while the Liège fortress ring and the Namur fortress ring were left to secure the frontiers.

Belgian troops in top hats, defending a Herstal suburb, just north-east of Liège, Belgium, August 1914.

On 2 Aug 1914, the German government sent an ultimatum to Belgium, demanding passage through Belgian territory (in order to outflank French defences), as German troops crossed the frontier of Luxembourg. On 3 August the Belgian Government refused German demands and the British Government guaranteed military support to Belgium, should Germany invade. Germany declared war on France and the British government ordered general mobilisation. On 4 August the British government sent an ultimatum to Germany and declared war on Germany at midnight on 4/5 August. Belgium severed diplomatic relations with Germany and Germany declared war on Belgium. German troops crossed the Belgian frontier and attacked Liège.

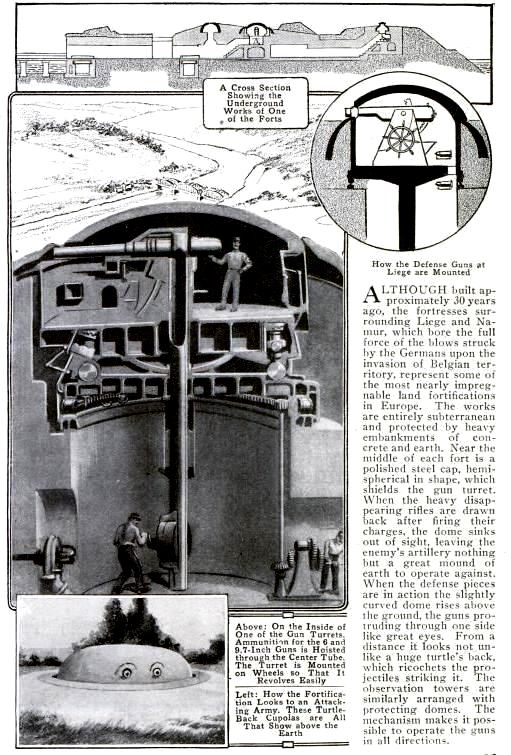

Liège Forts

Liège is situated at the confluence of the Meuse, which at the city flows through a deep ravine and the Ourthe, between the Ardennes to the south and Maastricht (in the Netherlands) and Flanders to the north and west. The city lies on the main rail lines from Germany to Brussels and Paris, which Schlieffen and Moltke planned to use in an invasion of France. Much industrial development had taken place in Liège and the vicinity, which presented an obstacle to an invading force. The main defences were a ring of twelve forts 6–10 km (3.7–6.2 mi) from the city, built in 1892 by Henri Alexis Brialmont, the leading fortress engineer of the nineteenth century. The forts were sited about 4 km (2.5 mi) apart to be mutually supporting but had been designed for frontal, rather than all-round defence.

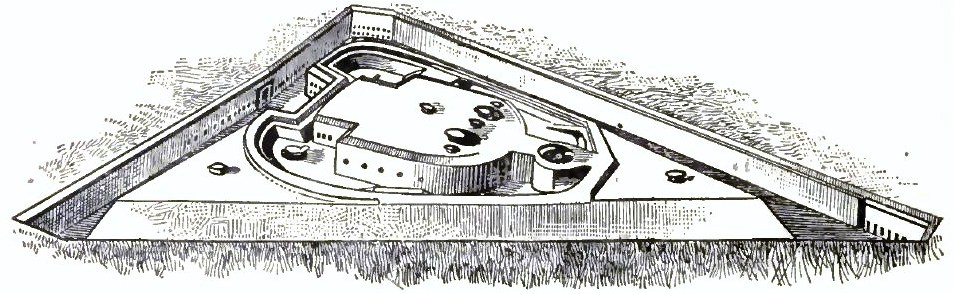

Triangular Brialmont fort, 1914.

Pentagonal Brialmont fort, 1914.

(Internet Archive Book Image)

Drawings illustrating the external appearance and internal structure of the Cupola Forts of Liège.

(Popular Mechanics Magazine Image, October 1914)

Drawings of Belgian Cupola Forts.

The forts were five large triangular (Barchon, Fléron, Boncelles, Lancin, and Pontisse), four small triangular (Evegnée, Hollogne, Lantin and Liers) and two small square forts (Chaudfontaine and Embourg). The forts were built of concrete, with a surrounding ditch and barbed-wire entanglements; the superstructures were buried and only mounds of concrete or masonry and soil were visible. The large forts had two armoured turrets with two 210 mm (8.3 in) guns each, one turret with two 150 mm (5.9 in) guns and two cupolas with a 210 mm (8.3 in) howitzer each. Four retractable turrets contained a 57 mm (2.2 in) quick-firer each, two before the citadel and two at the base. A retractable searchlight was built behind the 150 mm turret with a range of 2–3 km (1.2–1.9 mi). Small forts had a 210 mm (8.3 in) howitzer cupola and three of the quick-firers. The heavy guns and quick-firers used black powder ammunition, long superseded in other armies, which raised clouds of smoke and obscured the view of the fortress gunners. The 150 mm (5.9 in) guns had the greatest range at 8,500 m (9,300 yd) but the black powder smoke limited the realistic range to about 1,500 m (1,600 yd). The forts contained magazines for the storage of ammunition, crew quarters for up to 500 men and electric generators for lighting. Provision had been made for the daily needs of the fortress troops but the latrines, showers, kitchens and the morgue had been built in the counterscarp, which could become untenable if fumes from exploding shells collected, because the forts were ventilated naturally.

(Demis illustration)

Map of fortresses around Liege in Belgium. Blue indicates forts constructed 1888-1891; those in red were constructed in the 1930s.

The forts could communicate with the outside by telephone and telegraph but the wires were not buried. Smaller fortifications and trench lines in the gaps between the forts had been planned by Brialmont but had not been built. The fortress troops were not at full strength and many men were drawn from local guard units, who had received minimal training due to the reorganisation of the Belgian army begun in 1911, which was not due to be complete until 1926. The forts also had ca. 26,000 soldiers and 72 field guns of the 3rd Infantry Division and 15th Infantry Brigade to defend the gaps between forts, c. 6,000 fortress troops and members of the paramilitary Garde Civique, equipped with rifles and machine-guns. The garrison of c. 32,000 men and 280 guns, was insufficient to man the forts and field fortifications. In early August 1914, the garrison commander was unsure of the troops which he would have at his disposal, since until 6 August it was possible that all of the Belgian army would advance towards the Meuse.

The terrain in the fortress zone was difficult to observe from the forts because many ravines ran between them. Interval defences had been built just before the battle but were insufficient to stop German infiltration. The forts were also vulnerable to attack from the rear, the direction from which the German bombardments were fired. The forts had been designed to withstand shelling from 210-mm (8.3 in) guns, which in 1890, were the largest mobile artillery in the world but the concrete used was not of the best quality and by 1914 the German army had much larger 420-mm howitzers, (L/12 420-mm (17-in) M-Gerät 14 Kurze Marine-Kanone) and Austrian 305-mm howitzers (Mörser M. 11). The Belgian 3rd Division (Lieutenant-General Gérard Léman) along with the attached 15th Infantry Brigade defended Liège. The division comprised five brigades and various other formations with c. 32,000 troops and 280 guns.

In the morning of 5 August, Captain Brinckman, the German Military Attaché at Brussels, met the Governor of Liège under a flag of truce and demanded the surrender of the fortress. Léman refused and an hour later, German troops attacked the east bank forts of Chaudfontaine, Fleron, Evegnée, Barchon and Pontisse, while an attack on the Meuse, below the junction with the Vesdre, failed. A party of German troops managed to get between Fort de Barchon and the river Meuse but was forced back by the Belgian 11th Brigade. From the late afternoon into the night, the German infantry attacked in five columns, two from the north, one from the east and two from the south. The attacks were supported by heavy artillery but the German infantry were repulsed with great loss. The attack at the Ourthe forced back the defenders between the forts, before counter-attacks by the 12th, 9th and 15th Brigades checked the German advance. Just before dawn, a small German raiding party tried to abduct the Governor from the Belgian headquarters in Rue Ste. Foi. Alarmed by gunfire in the street, Léman and his staff rushed outside and joined the guard platoon fighting the raiding party, which was driven off with twenty dead and wounded left behind.

German cavalry moved south from Visé to encircle the town; German cavalry patrols had been operating up to 20 km (12 mi) west of Liege, leading Léman to believe that the German II Cavalry Corps was encircling the fortified area from the north, though in fact the main body of that force was still to the east and did not cross the Meuse until 8 August, when the reservists had arrived. Believing he would be trapped, Léman decided that the 3rd Infantry Division and 15th Infantry Brigade should withdraw westwards to the Gete, to join the Belgian field army.

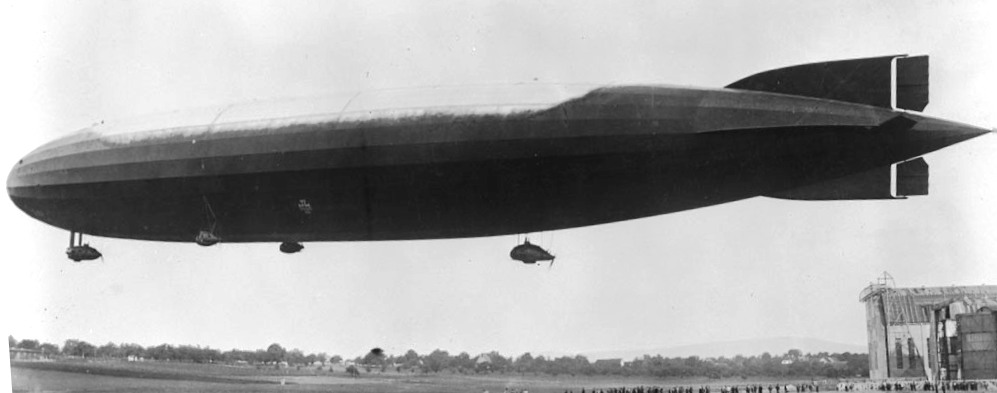

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 5013167)

German Zeppelin L-53 shot down on 11 August 1918, by Stuart Douglas Culley.

On 6 August, the Germans carried out the first air attack on a European city, when a Zeppelin (LZ 21 Class N, Z VI) airship bombed Liège and killed nine civilians. The airship’s inadequate lift kept it at low altitude so that bullets and shrapnel from defending fire holed the gasbags. The ship limped back to Cologne but had to be set down in a forest near Bonn, completely wrecking it.

Léman believed that units from five German corps confronted the defenders and assembled the 3rd Division between forts Loncin and Hollogne to begin the withdrawal to the Gete during the afternoon and night of 6/7 August. The fortress troops were concentrated in the forts, rather than the perimeter and at noon, Léman set up a new headquarters in Fort Loncin, on the western side of the city. German artillery bombarded the forts and Fort Fléron was put out of action when its cupola-hoisting mechanism was destroyed by the bombardment. On the night of 6/7 August German infantry were able to advance between the forts and during the early morning of 7 August, Ludendorff took command of the attack, ordered up a field howitzer and fought through Queue-du-Bois to the high ground overlooking Liège and captured the Citadel of Liege. Ludendorff sent a party forward to Léman under a flag of truce to demand surrender but Léman refused.

Bülow gave command of the siege operations at Liège to General Karl von Einem, the VII Corps commander with the IX and X Corps under his command. The three corps had been ordered to advance over the Belgian border on 8 August. At Liège, on 7 August, Emmich sent liaison officers to make contact with the brigades scattered around the town. The 11th Brigade advanced into the town and joined the troops there on the western fringe. The 27th Brigade arrived by 8 August, along with the rest of the 11th and 14th brigades. Fort Barcheron fell after a bombardment by mortars and the 34th Brigade took over the defence of the bridge over the Meuse at Lixhe. On the southern front the 38th and 43rd Brigades retreated towards Theux, after a false report that Belgian troops were attacking from Liège and Namur. On the night of 10/11 August Einem ordered that Liège be isolated on the eastern and south-eastern fronts by the IX, VII and X corps as they arrived and allotted the capture of forts Liers, Pontisse, Evegnée and Fléron to IX Corps and Chaudfontaine and Embourg to VII Corps as X Corps guarded the southern flank.

Before the orders arrived, fort Evegnée was captured after a bombardment. IX Corps isolated fort Pontisse on 12 August and began a bombardment of forts Pontisse and Fléon during the afternoon, with 380-mm (15- in) coastal mortars and Big Bertha 420-mm (17-in) siege howitzers. The VII Corps heavy artillery began to fire on fort Chaudfontaine, fort Pontisse was surrendered and IX Corps crossed the Meuse to attack fort Liers. Fort Liers fell in the morning of 14 August and the garrison of fort Fléron surrendered in the afternoon, after a Minenwerfer bombardment. The X Corps and the 17th Division were moved to the north and VII Corps to the south of the Liège–Brussels railway and on 15 August, a bombardment began on the forts to the west of the town. Fort Boncelles fell in the morning and fort Lantin in the afternoon; fort Loncin was devastated by the 420-mm guns and Léman was captured. Forts Hollogne and Flémalle were surrendered on the morning of 16 August after a short bombardment.

German soldiers in a car wait for Belgian attack, on the streets of Liège, Aug 1914.

German troops at Place Saint Lambert, Liège, Aug 1914. (Bibliothèque Ulysse Capitaine Photo)

By the morning of 17 August, the German 1st Army, 2nd Army and 3rd Army were free to resume their advance to the French frontier. The Belgian field army withdrew from the Gete towards Antwerp from 18–20 August and Brussels was captured unopposed on 20 August. The siege of Liège had lasted for eleven days, rather than the two days anticipated by the Germans. For 18 days, Belgian resistance in the east of the country had delayed German operations, which gave an advantage to the Franco-British forces in northern France and in Belgium.

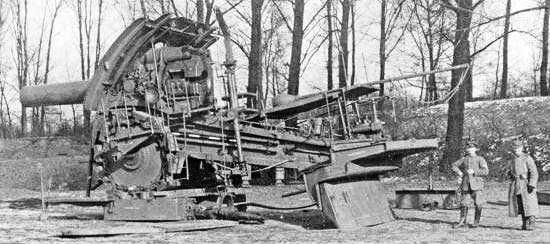

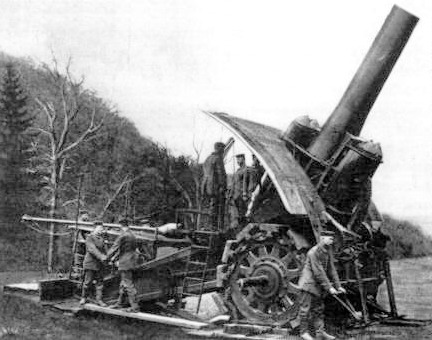

Big Bertha (Dicke Bertha, ‘Fat (or heavy) Bertha’) is the name of a type of super-heavy siege artillery developed by the armaments manufacturer Krupp in German and used in both the First and Second World Wars.

Big Bertha (Dicke Bertha, ‘Fat (or heavy) Bertha’) is the name of a type of super-heavy siege artillery developed by the armaments manufacturer Krupp in Germany and used in both the First and Second World Wars. Its official designation was the L/12, Type M-Gerät 14 (M-Equipment 1914) Kurze Marine-Kanone (“short naval gun”, a name intended to conceal the weapon’s real purpose). Its barrel diameter calibre was 420-mm (16.5-in)

The M-Gerät 14 howitzer was a road-mobile weapon mounted on a two-wheeled field type carriage of conventional construction. It used a conventional Krupp sliding-wedge breech, and fired shells of around 830 kg. Fully assembled it weighed 43 tons. Special steel “mats” were developed, onto which the wheels were driven, with a steel aiming arc at the rear of the carriage that allowed limited traverse. This aiming arc was fitted with a massive “spade” that was buried in the ground and which helped anchor the weapon. To prevent the weapon bogging down in muddy roads the guns were equipped with Radgürteln, feet attached to the rim of the wheels to reduce ground pressure. Krupp and Daimler developed a tractor for the Bertha, though Podeus motor ploughs were also used to tow the guns, which were broken down into five loads when on the road.

Only two operational M-Gerät were available at the beginning of the First World War, although two additional barrels and cradles had apparently been produced by that time. The two operational M-Geräte formed the Kurze Marine Kanone Batterie (KMK) No. 3; the 42 cm contingent contained four additional Gamma Geräte organized in two batteries, and one more Gamma became operational two weeks into the war as “half-battery”. They were used to destroy the Belgian forts at Liège, Namur and Antwerp, and the French fort at Maubeuge, as well as other forts in northern France. Bertha proved very effective against older constructions such as the Belgian forts designed in the 1880s by Brialmont, destroying several in a few days. The first wartime shot of an M-Gerät was fired against Fort Pontisse on the outskirts of Liege on 12 August 1914. The most spectacular success was against the nearby Loncin, which exploded after taking a direct hit to its ammunition magazine. The concrete used in the Belgian forts was of poor quality, and consisted of layers of concrete only, with no steel reinforcement.

(Rama Photo)

Model of the road-mobile “M-Gerät” (M-device) in the Paris Army Museum.

Big Bertha gained a strong reputation on both sides of the lines due to its early successes in smashing the forts at Liege. The German press went wild with enthusiasm and declared the Bertha a Wunderwaffe. Later during the German assault upon Verdun in February 1916, it proved less effective, as the newer construction of this fort, consisting of concrete reinforced with steel, could mostly withstand the large semi-armour-piercing shells of the Berthas. Only Fort Vaux was severely damaged during this event, when the shells destroyed the fort’s water storage supply, leading to the surrender of the fort.

A total of 12 complete M-Gerät were built; besides the two available when the war started, 10 more were built during the war. This figure does not include additional barrels; two extra barrels were already available before the war started, and possibly up to 20 barrels were built, though some sources state 18. As the war ground on, several Berthas were destroyed when their barrels burst due to faulty ammunition. Later in the Great War, an L/30 30.5-cm barrel was developed and fitted to some Bertha carriages to provide longer-range with lighter fire. These weapons were known as the Schwere Kartaune or Beta-M-Gerät.

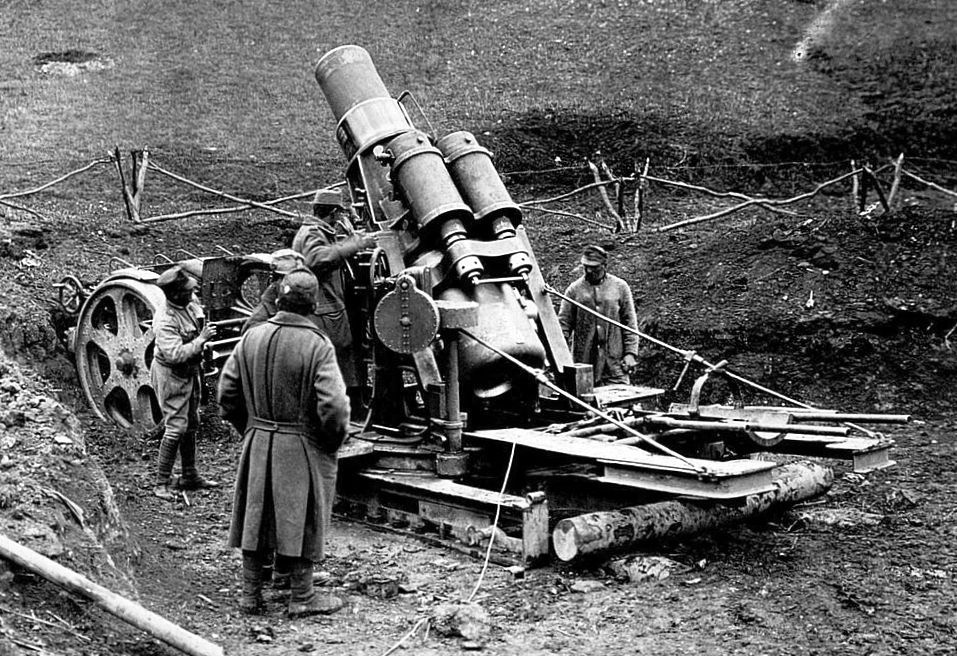

(Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Photo)

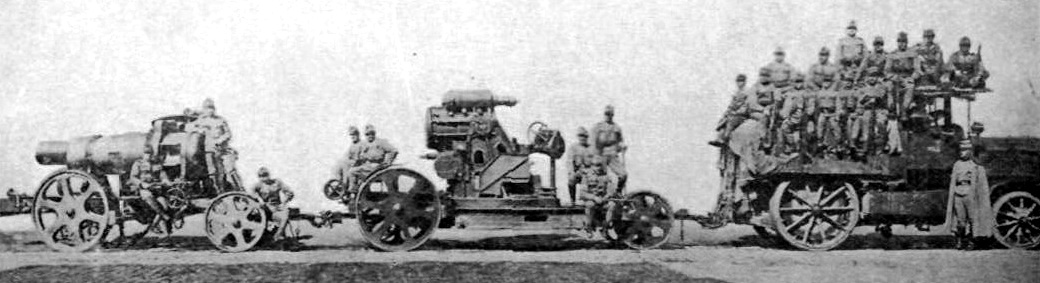

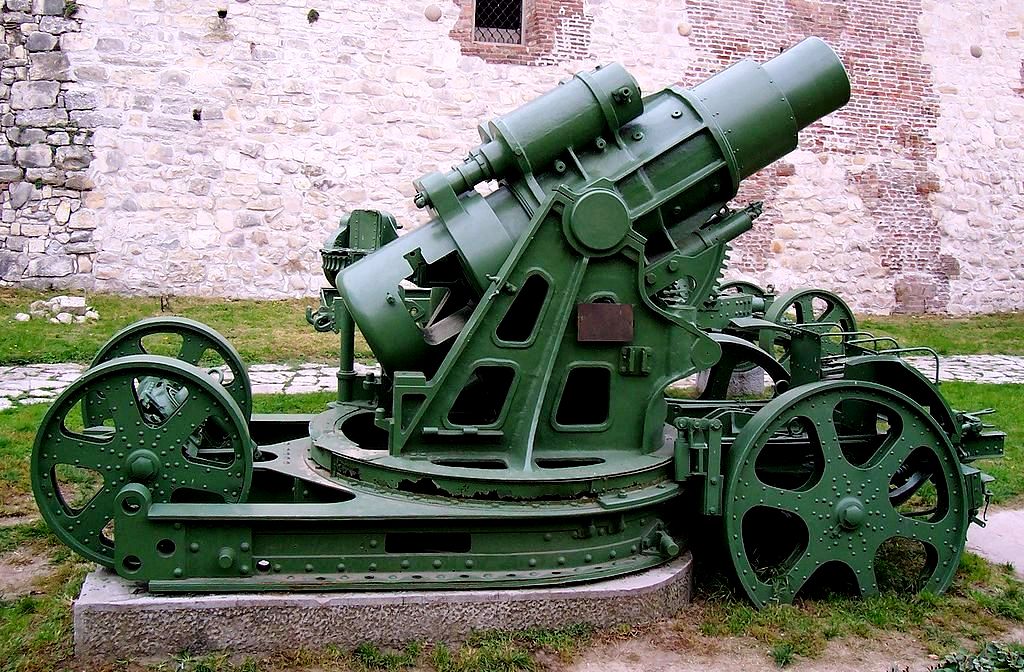

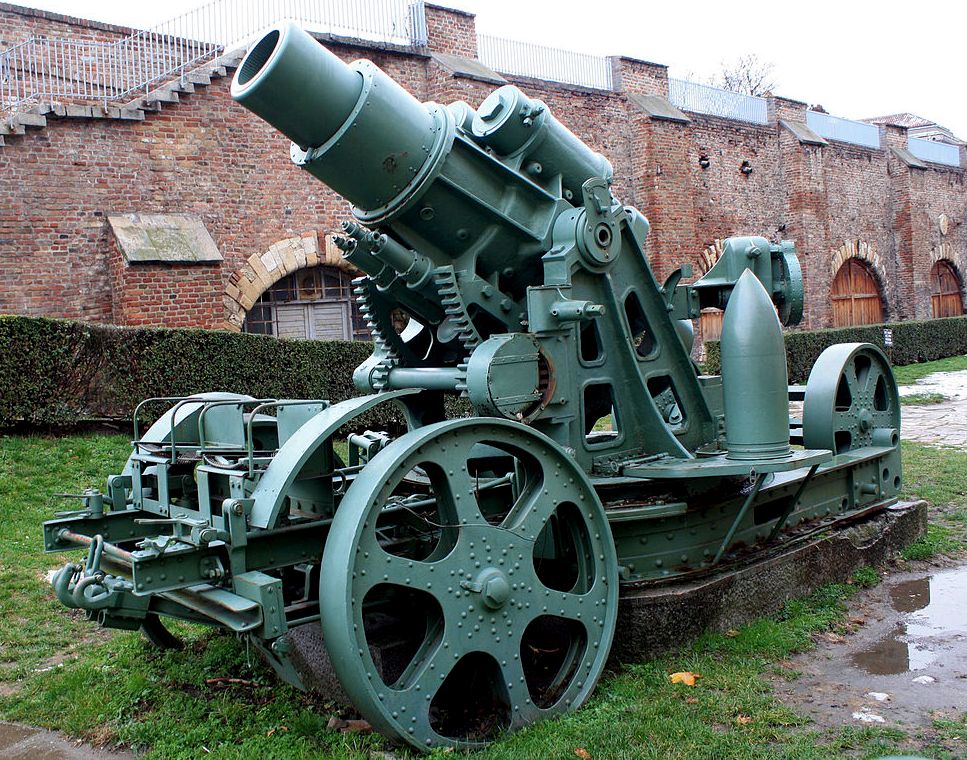

The Škoda 30.5 cm Mörser M.11 was a siege howitzer produced by Škoda Works and used by the Austro-Hungarian Army during the First World War and by the German Army in the Second World War. The weapon was able to penetrate 2 m (6 ft 7 in) of reinforced concrete with its special armour-piercing shell, which weighed 384 kg (847 lb). The weapon was transported in three sections by a 100-horsepower 15 ton Austro-Daimler road tractor M.12. It broke down into barrel, carriage and firing platform loads, each of which had its own trailer. It could be assembled and readied to fire in around 50 minutes.

Austro-Hungarian Škoda 30.5 cm Mörser M.11 barrel, body, being towed by a motor tractor, together with its complete crew, ca 1914.

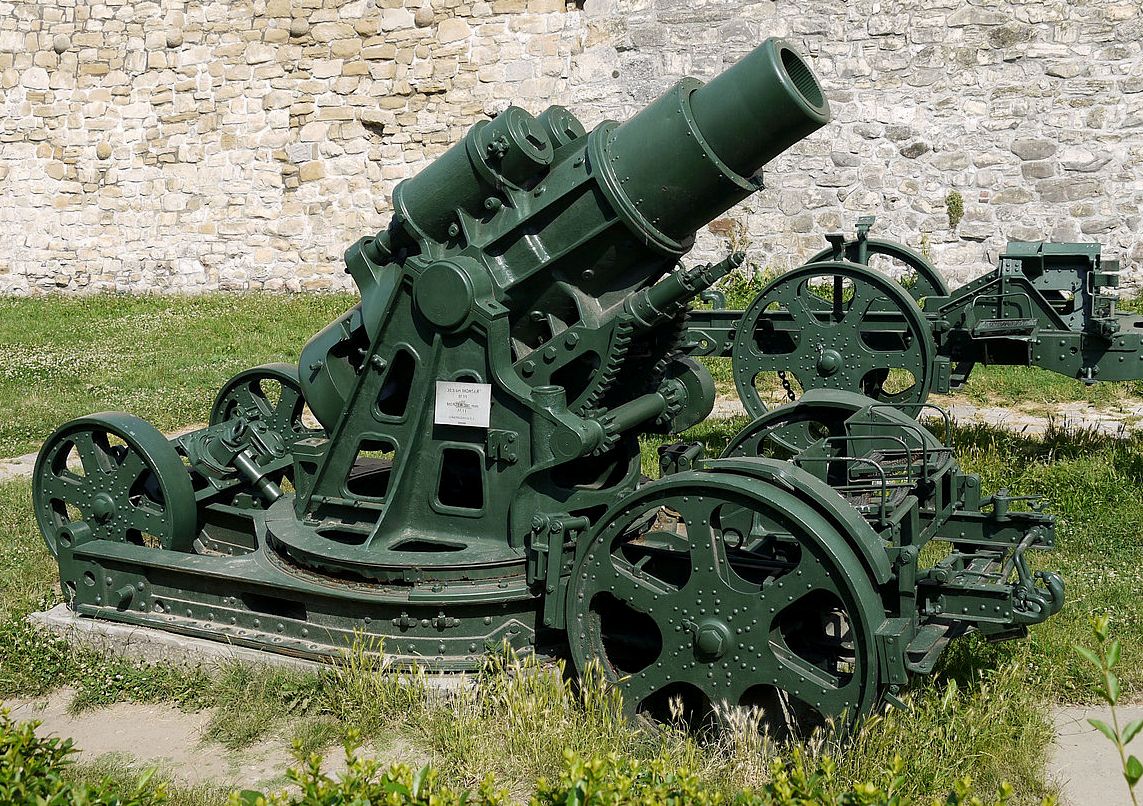

(Salix39 Photo)

(Nikola Smolenski Photo)

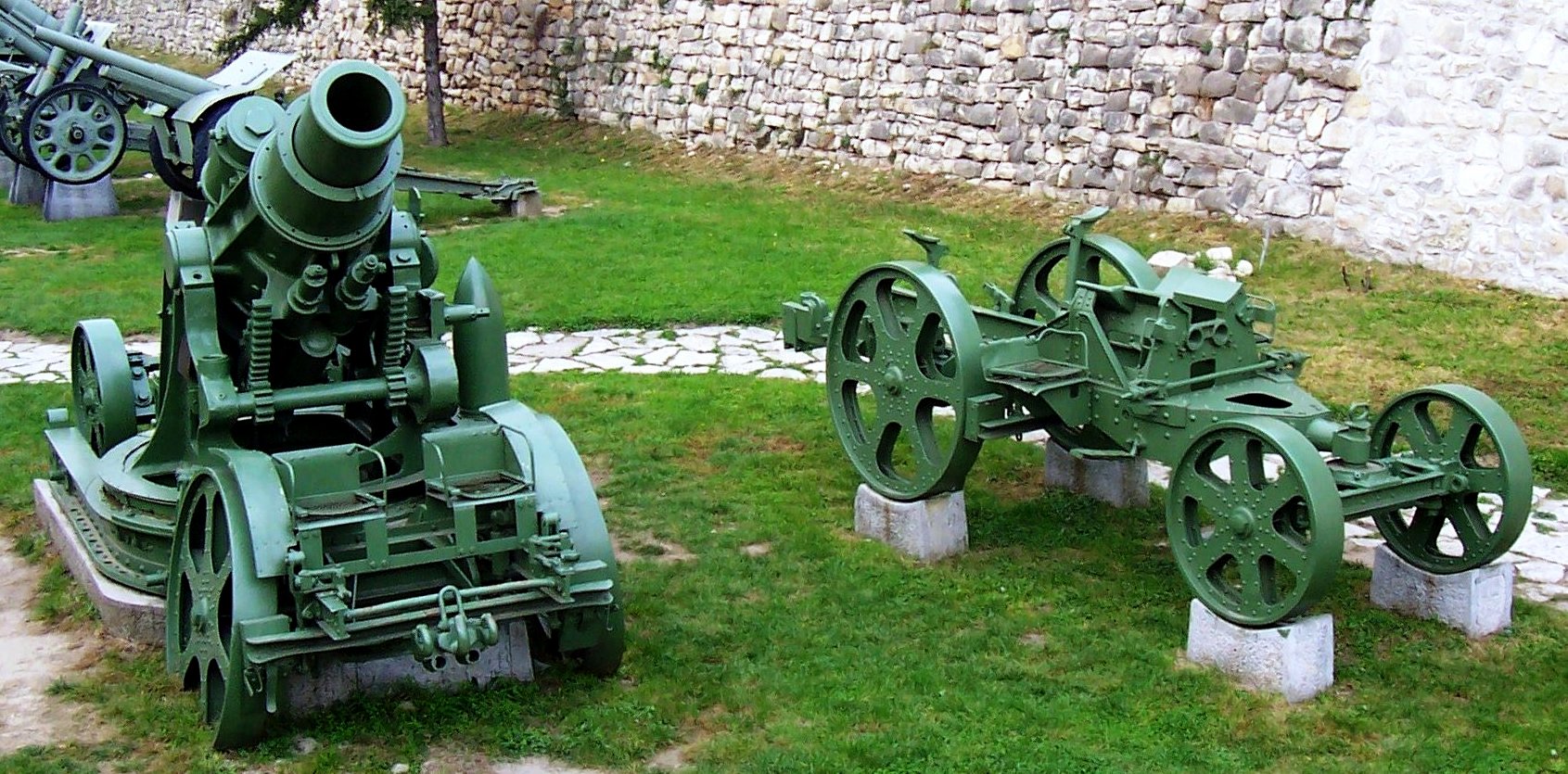

(Nikola Smolenski Photo)

Škoda 30.5 cm Mörser M.11 howitzer with its transport cart. For transport the barrel would be removed from the body and placed on the cart. This one is on display at the Belgrade Military Museum, Serbia.

(Sr?an Popovi? Photo)

Škoda 30.5cm Mörser M.11used by Austro-Hungarians during the Siege of Belgrade in the First World War and by the Yugoslav Royal Army postwar, part of Belgrade Military Museum outer exhibition at Kalemegdan fortress.

The mortar could fire two types of shell, a heavy armour-piercing shell with a delayed action fuse weighing 384 kg, and a lighter 287 kg shell fitted with an impact fuze. The light shell was capable of creating a crater 8 meters wide and 8 meters deep, as well as killing exposed infantry up to 400 m (440 yd) away. The weapon required a crew of 15–17, and could fire 10 to 12 rounds an hour. After firing, it automatically returned to the horizontal loading position.

Eight Mörsers were loaned to the German Army and they were first fired in action on the Western Front at the start of the First World War. They were used in concert with the Krupp 42-cm howitzer (Big Bertha) to destroy the rings of Belgian fortresses around Liège, Namur and Antwerp (Forts Koningshooikt, Kessel and Broechem). While the weapon was used on the Eastern, Italian and Serbian fronts until the end of the war, it was only used on the Western front at the beginning of the war.

Photograph of the destroyed fortification at Liège after it was struck by a shell from the Krupp siege gun. (“Popular Mechanics” Magazine Photo, November 1914)

The effect of German and Austrian super-heavy artillery on French and Belgian fortresses in 1914, led to a loss of confidence in fortifications; much of the artillery of fortress complexes in France and Russia was removed to reinforce field armies. At the Battle of Verdun in 1916, the resilience of French forts proved to have been underestimated.

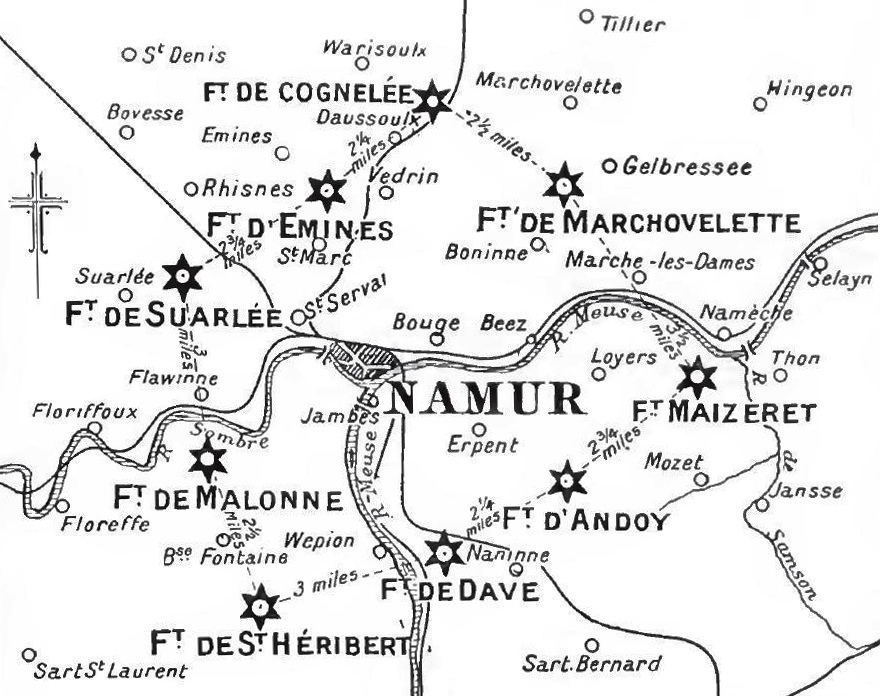

Map of the Fortresses defending Namur, ca 1914.

Siege of Namur

On 5 August the 4th Division at the Fortified Position of Namur, received notice from Belgian cavalry that they were in contact with German cavalry to the north of the fortress. More German troops appeared to the south-west on 7 August. OHL had, on the same day, ordered the 2nd Army units assembled near the Belgian border, to advance and send mixed brigades from the IX, VII and X corps to Liège immediately. Large numbers of German troops did not arrive in the vicinity of Namur until 19–20 August, too late to forestall the arrival of the 8th Brigade, which having been isolated at Huy, had blown the bridge over the Meuse on 19 August and retired to Namur. During the day the Guards Reserve Corps off the German 2nd Army arrived to the north of the fortress zone and the XI Corps of the 3rd Army, with the 22 Division and the 38th Division, arrived to the south-east.

A siege train including one Krupp 420 mm (17- in) howitzer and four Austrian 305 mm (12- in) mortars, accompanied the German troops and on 20 August, Belgian outposts were driven in; next day the German super-heavy guns began to bombard the eastern and south-eastern forts. The Belgian defenders had no means of keeping the German siege guns out of range or engaging them with counter-battery fire, by evening two forts had been seriously damaged and after another 24 hours the forts were mostly destroyed. Two Belgian counter-attacks on 22 August were defeated and by the end of 23 August, the northern and eastern fronts were defenceless, with five of the nine forts in ruins. The Namur garrison withdrew at midnight to the south-west and eventually managed to rejoin the Belgian field army at Antwerp; the last fort was surrendered on 25 August 1914.

(Edmonds, J.E. (1926). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914: Mons, the Retreat to the Seine, the Marne and the Aisne August–October 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents, by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan)

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3329046)

One of the Forts of Namur showing emplacements destroyed, November 1918.

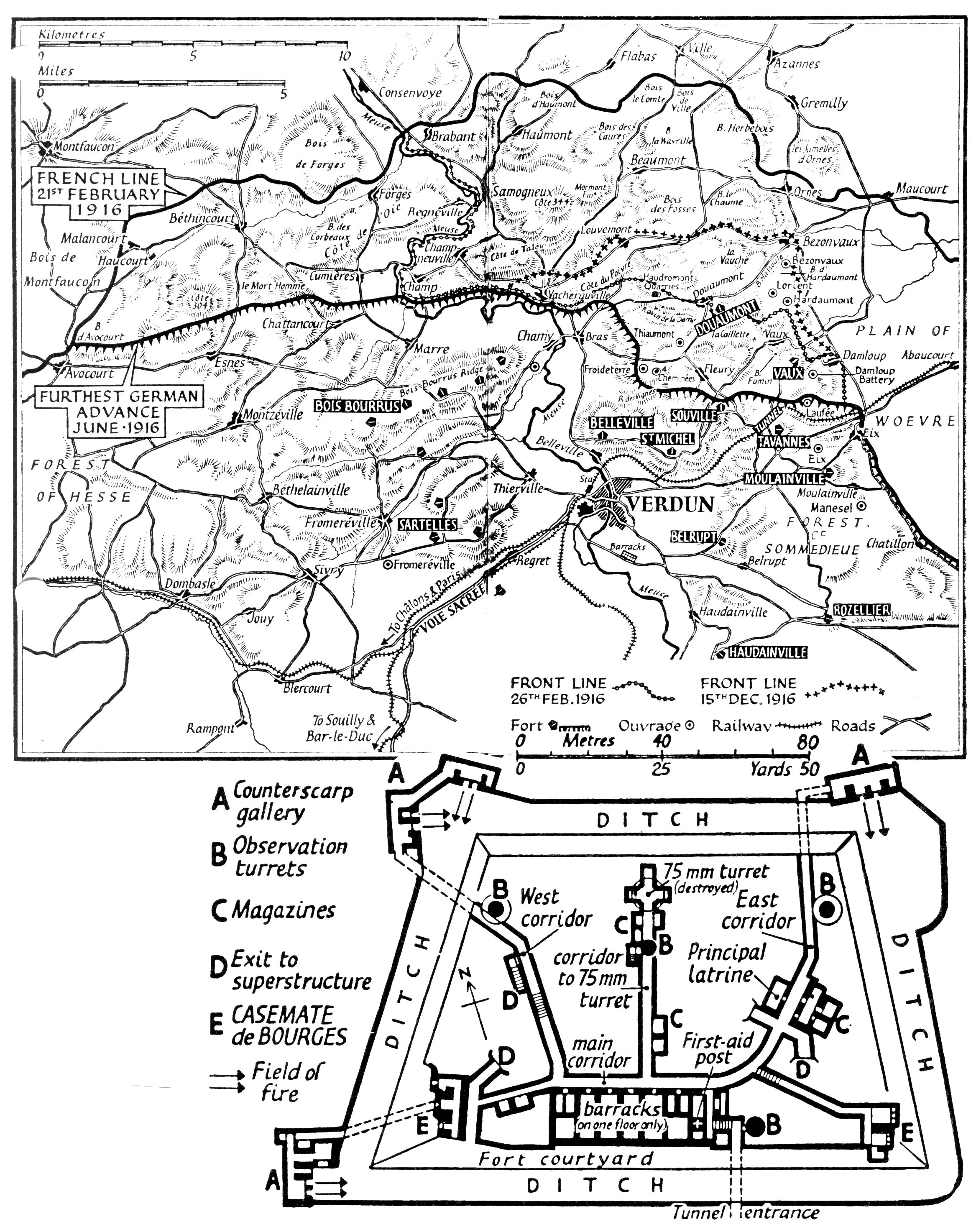

Verdun, 1916

(Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R29963)

During the First World War, Germany’s General Falkenhayn drafted a plan designed to indirectly strike at Britain by striking a blow at one of her allies.[263] He examined France, and looked for a seemingly impregnable place that could be assaulted on a narrow front with powerful artillery support. He chose the fortress of Verdun. It had originally served as a barrier across the wooded valley of the river Meuse, and Vauban had designed its enceinte. It was strengthened in the 1870s when a circle of forts was erected, and 1855 when another fort was built about five miles outside of town. Subsequently reinforced with steel and concrete, these detached forts put a strong defensive ring around Verdun itself, making it a fairly difficult fortress to assault. For this reason the allies had great difficulty determining what Falkenhayn’s intentions were, as he assembled a huge force on the western front in 1916. 32 divisions were arrayed against the British lines, and another 14 (later increased to 30) divisions were placed opposite Verdun.

It was Falkenhayn who had sanctioned the first use of gas at Ypres, advocated unrestricted submarine warfare and promiscuous bombing of built up areas in reprisal for Allied air raids. Ruthless he may have been, but his strategic appreciation’s were said to have been brilliant, and much of the credit for bringing Germany up out of the low point of disaster on the Marne belongs to Falkenhayn. He had a seemingly limitless capacity for work, and drove himself and his staff to great lengths. He would prove to be a formidable opponent.[264]

Marshal Petain who commanded the 2nd French Army organized the defense of the fortress. Generals Nivelle and Mangin led the defenders, although the actual commander of Verdun was General Herr. The French forces were aware that something was coming on 16 January 1916, but apart from moving reserve forces forward, took no action. The Germans put in a dummy attack at Lihons, but the real assault was preceded by a prolonged bombardment by German batteries east, west and north of the Verdun salient shelling the French positions along a 25-mile front. With only two army corps to hold back seven, the French had to take advantage of the ground. The engineers had added a number of protecting tunnels where the defenders could keep out of range of flame-throwers, deep saps in the woods with reliable cover against flying shrapnel, wire entanglements, land mines and forbidding barriers loaded with high explosive ready to go off at the first intruders touch.

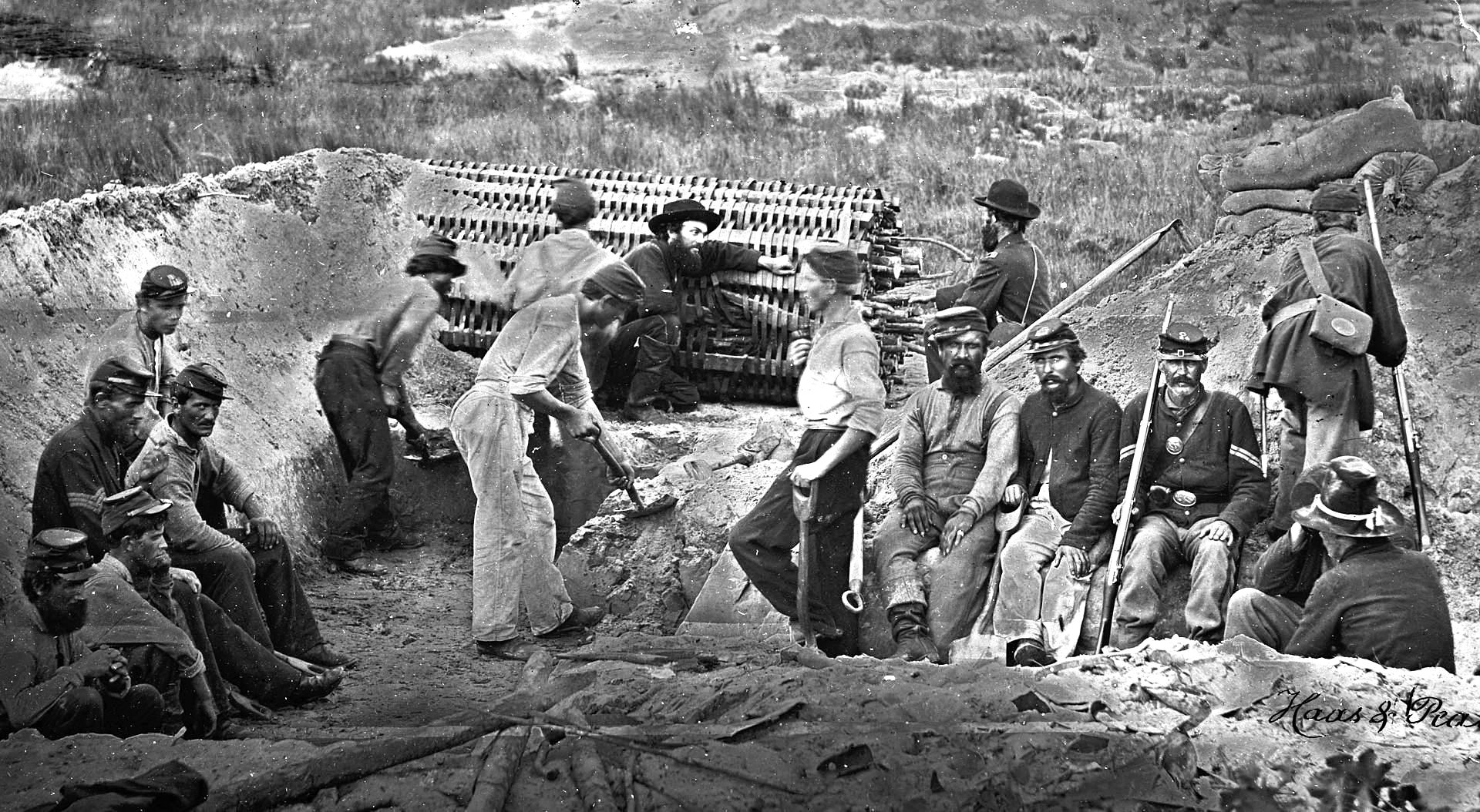

Sapping

Sapping is a term used in siege operations to describe any trench excavated near an attacked, defended fortification, under defensive small arms or artillery fire. The trench, referred to as a “sap”, is intended to advance a besieging army’s position in relation to the works of an attacked fortification. The sap is excavated by brigades of trained soldiers, often called sappers. The sappers dig the trenches or specifically instruct the troops of the line to do so.

By using the sap (trench) the besiegers could move closer to the walls of a fortress, without exposing the sappers to direct fire from the defending force. To protect the sappers, trenches were usually dug at an angle in zig-zagged pattern (to protect against enfilading fire from the defenders) and at the head of the sap a defensive shield made of gabions (or a mantlet) could be deployed.

Once the saps were close enough, siege engines or guns could be moved though the trenches and got closer to the fortification From this closer firing point, to fire at the fortification. The goal of firing is to batter a breach in the curtain walls, to allow attacking infantry to get past the walls . Prior to the invention of large pieces of siege artillery, miners could start to tunnel from the head of a sap to undermine the walls. A fire or gunpowder would then be used to create a crater into which a section of the fortifications would fall creating a breach.

(Library of Congress Photo)

Union troops of the 1st New York Volunteer Engineer Regiment digging a sap with a sap roller on Morris Island, 1863.

(Bundesarchiv Photo)

German soldiers with periscope in a trench on the Western Front, ca 1916.

After the heavy bombardment, the Germans concentrated heavy howitzers on a small sector of entrenchments near Brabant and the Meuse. 12” shells exploding fairly close together quickly blasted the trenches out of existence. Then the other end of the front was subjected to the same bombardment, followed next by the target of Cannes wood in the center of the Verdun salient. The Germans were attempting to capture the first lines of trenches without using infantry until they could move reconnaissance patrols forward. The French however, had sited their machine-gunners and a number of light guns in concealed positions some distance away from the front line trenches. The German patrols were mown down and the main attack made very little progress.

Through persistent attacks, the Germans gradually wore down the French opposition and broke up their defensive works for a depth of three or four miles, driving the defenders out of Brabant and Haumont. The French lost Herbois wood on the right of the line, but managed to hold on to Hill 351. The slaughter in the Maucourt sector was particularly appalling, with large numbers of dead and wounded between Ornes and Vaux.

After heavy fighting on the left and in the center of the salient, the French forces near the Meuse attempted a counter-attack, but were forced to withdraw under accurate German shellfire. They withdrew to the Cote du Poivre (Pepper Hill), generally acknowledged to be the key to the defense system of Verdun. At this point, if the Germans had been able to advance to a position parallel to the Meuse, thousands of French troops would have been surrounded. French artillery fire under the command of General Herr halted the German advance at Vacherauville, just below the vital Pepper Hill.

More troops from both sides were moved up to reinforce their forward positions under the cover of February snows and mists. In spite of General Herr’s successful defense on Pepper Hill, he was relieved of his command on the recommendation of General Castelnau, the French Chief of Staff, by Joffre. An engineering officer expert at the handling of heavy artillery, Henri Philippe Petain, replaced him. Petain took on the task of reorganizing the defenses of Verdun.

(Photographisches Bild-und-Film-Amt)

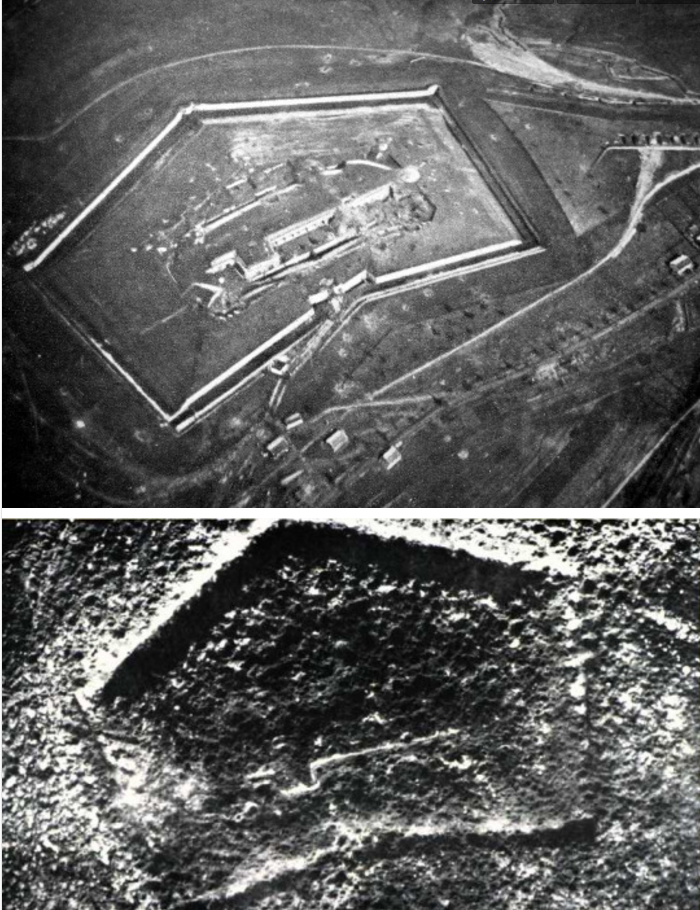

Fort Douamont early in the war, and after the bombardment, late 1916.

The Germans managed to capture the great armoured fort of Douaumont, the north-eastern pillar of the defenses of Verdun without having to fight for it, opening the way to Verdun itself. Not anticipating this “gift” the Germans did not follow up the initial opportunity it presented, and the delay allowed the French forces to throw extra bridges across the Meuse and to bring in relief divisions and more guns. Petain rotated his fresh troops, placing them where and when they could do the most good rather than jamming them into the congestion of Verdun all at once.

The Germans, now held up on the Douaumont plateau, exerted pressure on their right, attempting to capture “The Mort Homme,” (Dead Man Hill). The French forces held on. At great cost, the attackers took Forges, Bois des Corbeaux and Cumieres wood. Petain in turn hurled in more reinforcements, and strengthened his positions on the long ridge of Dead Man Hill. In the lull that followed, Petain was promoted and transferred, being replaced at Verdun by General Nivelle.

Over the battlefield an enormous air battle was kept up. Outmatched 5 to 1, the French lack of air superiority over Verdun contributed to enormous losses sustained on the ground. The technology of airpower was beginning to exert its first great effect on fortification. Although the Germans had air superiority they failed to cut the French supply lines, which would have sealed Verdun’s fate.[265]

Map of the Battle of Verdun.

Sometimes the bravest efforts are overcome by the severest privations. Fort Vaux was one of the last forts to fall, in an isolated and heroic action. Shelled by heavy long range artillery known as Big Berthas, besieged, attacked by gas and fire, cut off from France, with nothing more imposing than machine guns for its defense, it had held off the weight of the Crown Prince’s army for a week. Even after the Germans had actually penetrated the fort, they had been unable to advance more than thirty or forty yards underground in five days of fighting. The garrison had suffered about 100 casualties against the German losses of 2,678 men and 64 officers. The men had fought well, but the fort had simply run out of water. A nearly impregnable fort had in the end been defeated by thirst.[266]

Falkenhayn continued to withdraw divisions from other theaters of war, especially the Russian front, in spite of recommendations that the German losses be cut and the remaining troops withdrawn. Unfortunately, Falkenhayn realized that if he broke off the engagement, the reinforced French armies, now over 500,000 strong, would immediately switch over to the offensive. If he persisted however, there was a strong chance that he would fail. The steady drain on German military strength therefore continued until it was obvious that the breakthrough attempt at Verdun had failed. The Germans losses eventually totaled 337,000 men including 100,000 killed, and for France 377,231 of which 162,308 were killed or missing. The figures have varied, but the generally accepted figure for the combined casualties of both sides is over 700,000.[267]

Neither side “won” at Verdun. Horne summed it up as an indecisive battle in an indecisive war, both of which were unnecessary. Neither the French nor the German army would ever fully recover from this battle, and from this point forward the main burden of the war on the Western Front fell on Britain.[268]

An indirect effect of Verdun on siege warfare was the lasting impression of the survivability of the French forts against heavy artillery. This in turn led France to develop a new wall, its famous Maginot Line. The misplaced idea of putting the nation’s complete trust in this wall led directly to the downfall of France in 1940.[269]

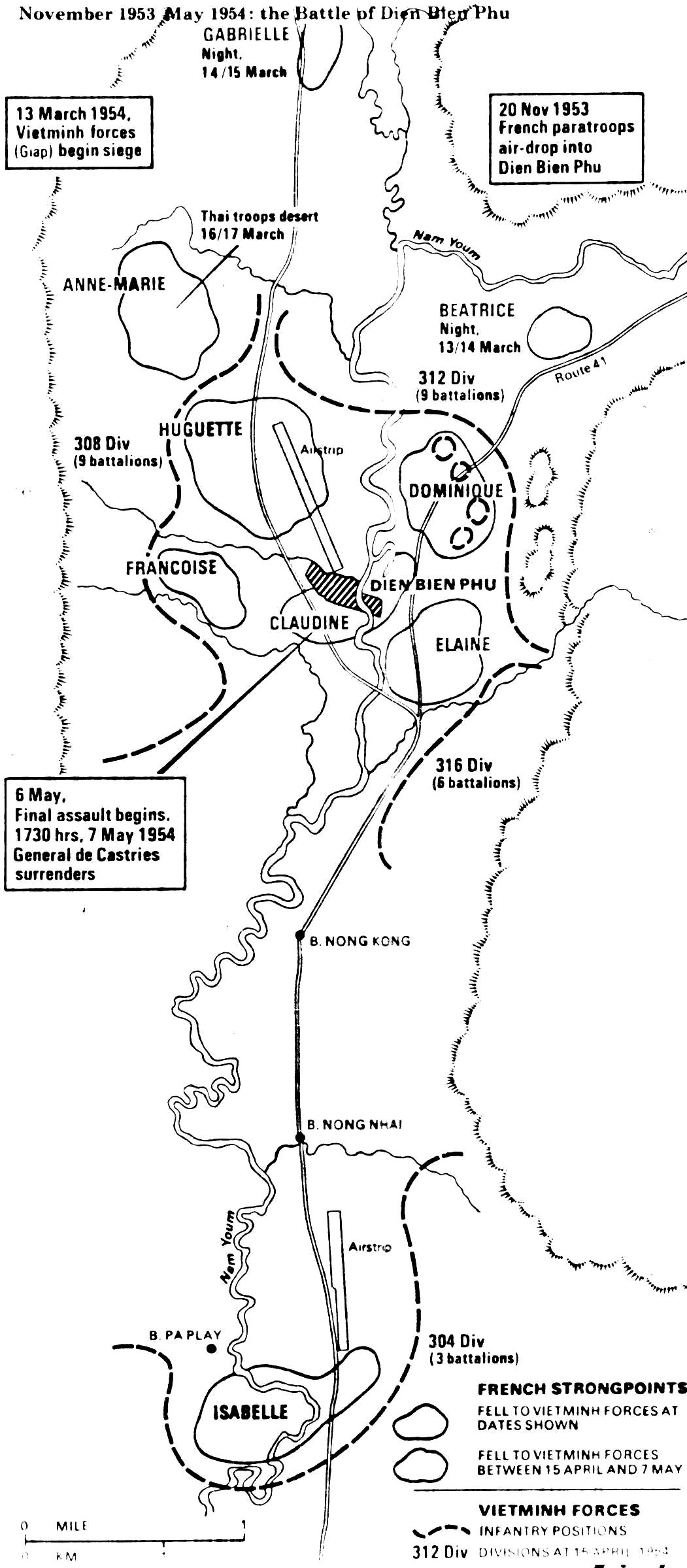

The Winter War, 1939-1940

The Winter War, also known as the First Soviet-Finnish War, was a war between the Soviet Union and Finland. The war began with a Soviet invasion of Finland on 30 November 1939, three months after the outbreak of the Second World War, and ended three-and-a-half months later with the Moscow Peace Treaty on 13 March 1940. Despite superior military strength, especially in tanks and aircraft, the Soviet Union suffered severe losses and initially made little headway. The League of Nations deemed the attack illegal and expelled the Soviet Union from the organization.

The Soviets made several demands, including that Finland cede substantial border territories in exchange for land elsewhere, claiming security reasons—primarily the protection of Leningrad, 32 km (20 mi) from the Finnish border. When Finland refused, the Soviets invaded. Most sources conclude that the Soviet Union had intended to conquer all of Finland, and use the establishment of the puppet Finnish Communist government and the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact’s secret protocols as evidence of this, while other sources argue against the idea of a full Soviet conquest. Finland repelled Soviet attacks for more than two months and inflicted substantial losses on the invaders while temperatures ranged as low as −43 °C (−45 °F). The battles focused mainly on Taipale in Karelian Isthmus, on Kollaa in Ladoga Karelia and on the Raate Road, in Kainuu, but there were also battles in Salla and Petsamo in Lapland. After the Soviet military reorganized and adopted different tactics, they renewed their offensive in February and overcame Finnish defences.

Hostilities ceased in March 1940 with the signing of the Moscow Peace Treaty in which Finland ceded 9% of its territory to the Soviet Union. Soviet losses were heavy, and the country’s international reputation suffered. Their gains exceeded their pre-war demands, and the Soviets received substantial territories along Lake Ladoga and further north. Finland retained its sovereignty and enhanced its international reputation. The poor performance of the Red Army encouraged German Chancellor Adolf Hitler to believe that an attack on the Soviet Union would be successful and confirmed negative Western opinions of the Soviet military. After 15 months of Interim Peace, in June 1941, Germany commenced Operation Barbarossa, and the Continuation War between Finland and the USSR began. (Wikipedia)

(Finnish Wartime Photograph Archive (SA-Kuva)

Dead Soviet soldiers and their equipment at Raate Road, Suomussalmi, after being encircled at the Battle of Raate Road, 1 January 1940.

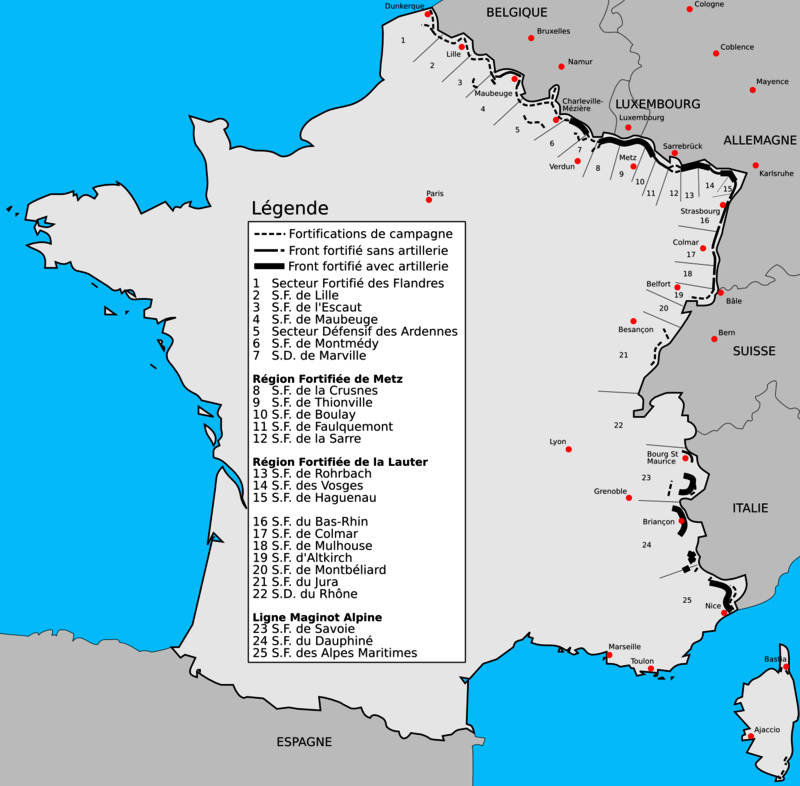

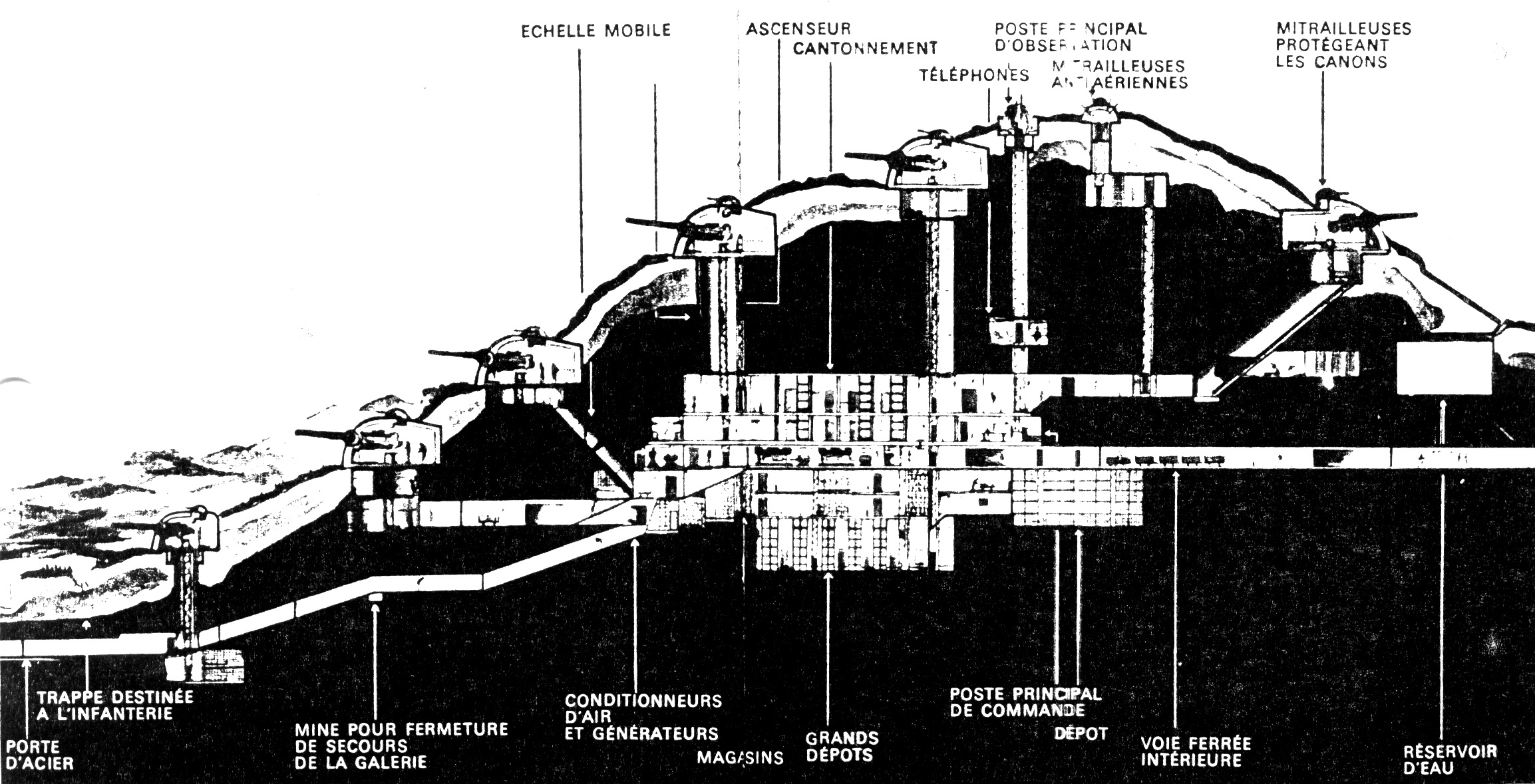

Maginot Line, 1939-1940

Map of the Maginot Line Defence system, 1939-1940.

Turret formations in a portion of the Maginot Line.

The end of the First World War saw the diminishing of experimentation and innovation in France as technology became increasingly more costly. Marshal Petain and General Debeney influenced their officer corps by their advocacy of the dogma of static prepared defenses. “Continuous prepared battlefields” on the frontiers and massed defensive artillery replaced maneuvers set around fortified regions. This new mode was systematized and symbolized by the construction of fixed fortifications from Switzerland to Luxembourg. This line was decided on by military commissions between 1922 and 1927, but always attributed to the war minister, Andre Maginot, who piloted the laws for its finance through parliament. Permanently garrisoned, the line was politically uncontentious by virtue of appearing strictly defensive. It was a prudent investment, for it afforded not only security to vulnerable industrial regions only recently recovered from Germany, but also protection for the two-week process of mobilization and concentration of the army’s reserves.[270]

Verdun may therefore have served its purpose in spite of the losses. Dupuy stated for example, that a defender’s chances of success are directly proportional to fortification strength, although he noted that others assert that like Verdun, defenses are attractive traps to be avoided at all costs. One of his key observations however, is that never in history has a defense been weakened by the availability of fortifications, and that defensive works always enhance combat strength. At the least they will delay an attacker and add to his casualties; at the best, fortifications will enable the defender to defeat the attacker. He noted that although the Maginot Line, the Mannerheim Line, the Siegfried Line, and the Bar Lev Line were overcome in battle, it was only because a powerful enemy was willing to make a massive and costly effort. In 1940, the Germans were so impressed by the defensive strength of the Maginot Line, that they bypassed it.[271]

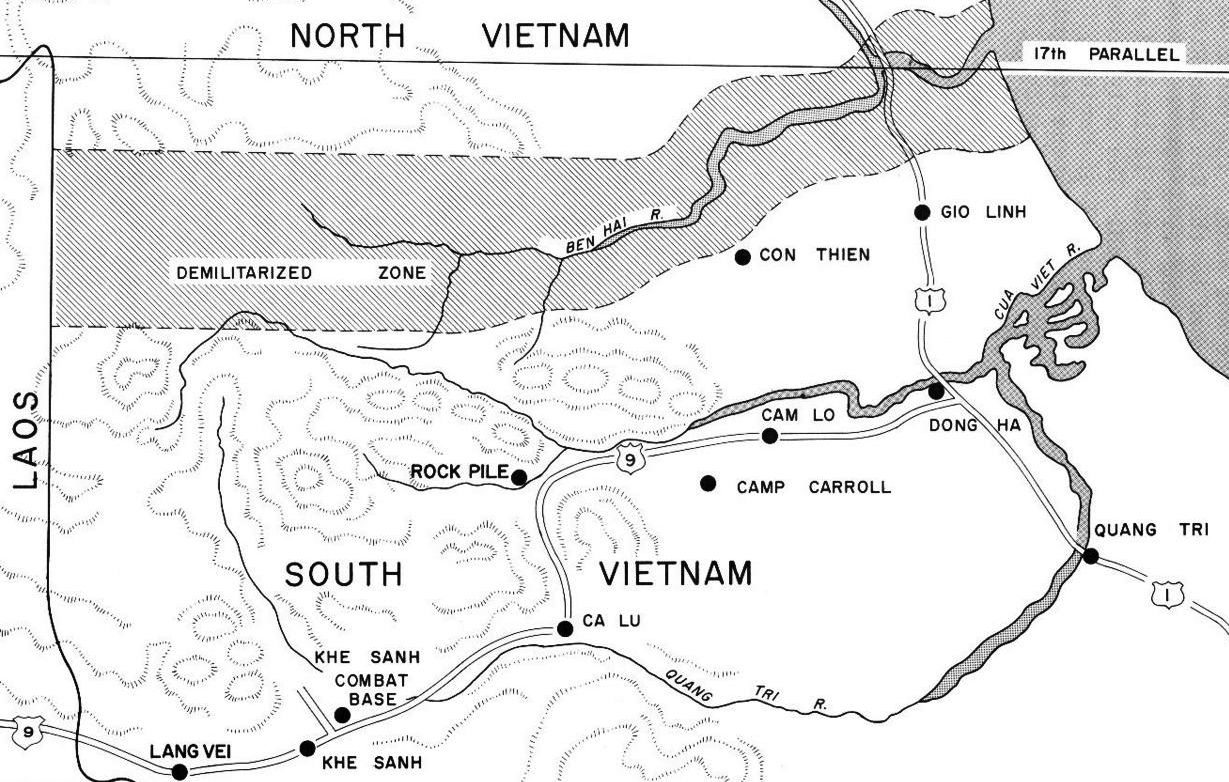

To further illustrate how quickly the times changed, Verdun fell in less than 24 hours on 14 May 1940, to the German Panzers, costing them less than 200 dead. Airborne forces had also played a key role in the German invasion, particularly in the attack launched against the Dutch fortress of Eban Emael and the Albert Canal bridges on 10 May 1940.[272]

Capture of Fort Eban Emael, 1940

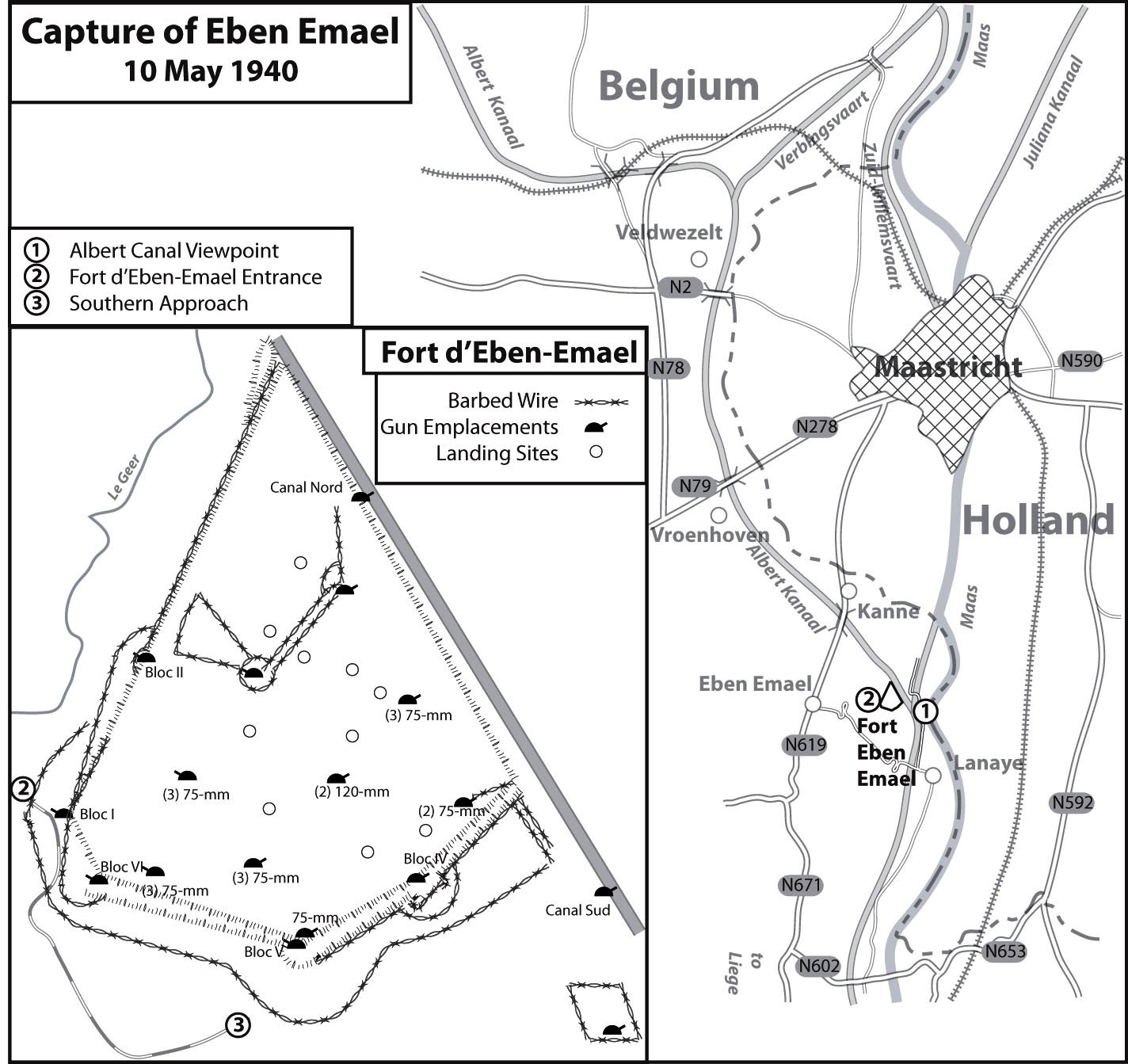

The German invasion of the Low Countries required that the Albert Canal and its extensive fortifications be captured in order to convince the Allies that the main German attack was to come through Belgium. The Belgians had built the canal after the First World War in order to deter any repetition of the 1914 German invasion.

(Romaine Photo)

Fort Eban Emael.

The key to this defensive system was the fortress of Eben Emael. Considered impregnable, and set on the west bank of the Canal, its guns were capable of dominating all crossing sites on the Mass river and the Albert Canal out to a range of 16 kilometers. Surrounded by carefully sited moats and anti-tank ditches, it had four rooftop casemates which could retract into the ground. The guns of the fortress were only part of the fort’s elaborate system of fire control, in which the firepower of Eben Emael was interlinked with the neighboring field works. The fortress was garrisoned with approximately 1200 officers and men, safely housed under 25 meters of concrete and well supplied with food, water and ammunition sufficient to withstand an indefinite siege.

Battle Map of Fort Eban Emael.

More importantly, the fort commanded the three bridges the Germans would need in their drive to outflank the French Maginot Line which lay to the north, and the complex of Belgian forts around Liege. The bridges over the canal at Canne, Vroenhofen and Veldwezelt were well defended, each having a garrison of an officer and 11 men with anti-tank guns and automatic weapons. Reinforcements were also close at hand.[273]

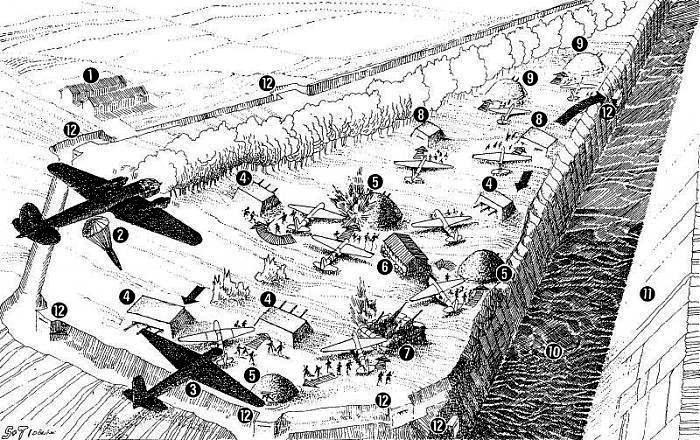

The Germans studied this formidable defensive system carefully, accumulating and collating detailed intelligence and interpreting the data with an eye to minute details. They built models and used them to devise special methods for its conquest. On the advice of Hanna Reitsch, a well-known aviatrix, Hitler agreed to the recommendation for a silent assault using troop-carrying gliders. Lieutenant-General Student confirmed the plan’s feasibility and nominated Hauptmann Walter Koch to carry it out.[274]

(Bundesarchiv Bild 101I-567-1519-18)

German DFS 230 Troop carrying glider.

(Bundesarchiv Photo)

German paratroops with a DFS-230 glider.

Hauptmann Walter Koch of the 1st Parachute Regiment made extensive use of a DFS-230 glider developed by General Student in training exercises, while a replica of the fortress at Eben Emael was constructed and subjected to different methods of demolition. Special 50 kg hollow charges were developed for piercing the reinforced concrete of the fortress. These charges would be placed by a team of 100 glider-borne sappers, who would land on the grassy roof of the fortress. Codenamed Granite, they were commanded by Lt Rudolf Witzig. Three assault groups codenamed Iron, Concrete and Steel were assigned to glide in and capture the key Albert Canal bridges. They were equipped with flamethrowers, machine guns, anti-tank sections, mortars and demolition teams. Trained to fight in small groups, Koch’s force was well prepared for the attack, which was set to go in one hour before dawn to achieve surprise.

Aircraft allocated to Assault Group Koch comprised 42 Ju-52 transports and glider tugs, and 42 DFS 230 gliders. Early on the morning of 10 May, the assault group set off from Koln-Wahn towards Maastricht, carrying a total of 493 officers and men.[275] Because surprise was essential, the operational plan called for the glider tugs to climb to a height over 8,200’ and release their gliders over Germany, allowing the gliders to fly silently to their objectives. Most of the gliders cast-off from their tugs over the fortress. Accurate landings at two of the bridge sites, Veldwezelt and Vroenhofen, resulted in total surprise and success, but at the third bridge at Canne, the German gliders had landed slightly too far away, and the Belgian defenders were able to hold off the attackers just long enough to obtain permission to destroy the bridge. The garrison blew it in the face of the German’s as they arrived.

Glider and paratroop landings at Eben Emael, illustration.

Surprise was crucial at Eban Emael, and it was also successfully gained. The nine gliders, streaming brake parachutes, skidded to a rest within 20 meters of landing. The sappers dashed out and began placing their deadly explosive charges on the inconspicuous roofs of the six most important casemates and 12 gun emplacements that threatened them and the bridges, detonating them as dawn came. The German engineers then entered and secured the top level of the fortress, effectively trapping the majority of the garrison in the rest of the fortress, from where they could do little damage.[276]

At first light, swarms of Luftwaffe dive?bombers appeared overhead, sealing off all reinforcement routes to the stricken fortress. Paratroops arrived in the daylight to reinforce the assailants. Swarms of dummy parachutists were also dropped to the west to further confuse the defense.

Elements of the 4th Panzer Division fought across the Mass River and made contact with the paratroopers and glider infantry at Veldwezelt at 1430. All through the night of 10 May, the Germans continued to batter away with their explosives, and at 1230 hours of the 11th of May 1940, the fort surrendered. Sixty of its garrison had been killed and 40 wounded and over 1,000 men marched out to be taken prisoner. The entire German force had lost only 6 men killed and 19 wounded. Hitler personally decorated Hauptman Koch’s special force, and the unit was later expanded into an airborne assault regiment.[277]

The loss of this “impregnable” fortress, led to the subsequent German successes against the Belgian army and its capitulation on 28 May 1940.[278] Dutch, French and British forces were then driven into the sea, which in turn led to an armistice with France on 17 June 1940. Airborne forces had made a difference, and they would see more use as the war progressed, particularly during the Normandy invasion of 6 June 1944.

Siege of Tobruk, 1941

During the Second World War, Allied forces, mainly the Australian 6th Division, captured the Libyan port city of Tobruk on 22 January 1941. The Australian 9th Division (“The Rats of Tobruk”) pulled back to Tobruk to avoid encirclement after actions at Er Regima and Mechili and reached Tobruk on 9 April 1941 where prolonged fighting against German and Italian forces followed. Although the siege was lifted after 241 days by Operation Crusader in November 1941, a renewed offensive by Axis forces under General Erwin Rommel the following year resulted in Tobruk being captured in June 1942 and held by the Axis forces until November 1942, when it was recaptured by the Allies.

(IWM Photo E 4792)

Australian troops occupy a front line position at Tobruk, 13 Aug 1941. Between April and December 1941 the Tobruk garrison, comprising British, Australian and Polish troops, was besieged by Rommel’s forces. It fell to the Germans after the battle of Gazala on 21 June 1942 but was recaptured five months later.

Siege of Leningrad, 1942

Medieval sieges tended to last less than 40 days (the length of service owed by serfs to their overlords). In later years a determined attacker would stay until the fort, castle or city either fell or was relieved. During the Second World War, German forces kept the city of Leningrad under siege for 900 days. For the people of this city, today known once again as St. Petersburg, the Blokada (the Siege) of Leningrad is an important part of their heritage and for the older generations it brings memories that they will never forget.

(Soviet Army Photo)

Russians soldiers in the trenches, defending Leningrad.

German troops approached Leningrad within two and a half months of their invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941.[279] By 8 September 1941 they had outflanked the Red Army and had fully encircled Leningrad, at which point the siege began. The siege lasted from 8 September 1941 through to 27 January 1944, roughly 900 days. (In contrast, the siege of Moscow lasted only from 2 October to 5 December 1941).

(Boris Kudoyarov Photo, RIAN Archive)

Soviet anti-aircraft gunners defending Leningrad.

(Boris Kudoyarov Photo, RIAN Archive)

Soviet machinegunners defending Leningrad.