Sieges, Part 5, Invasions and Civil Wars

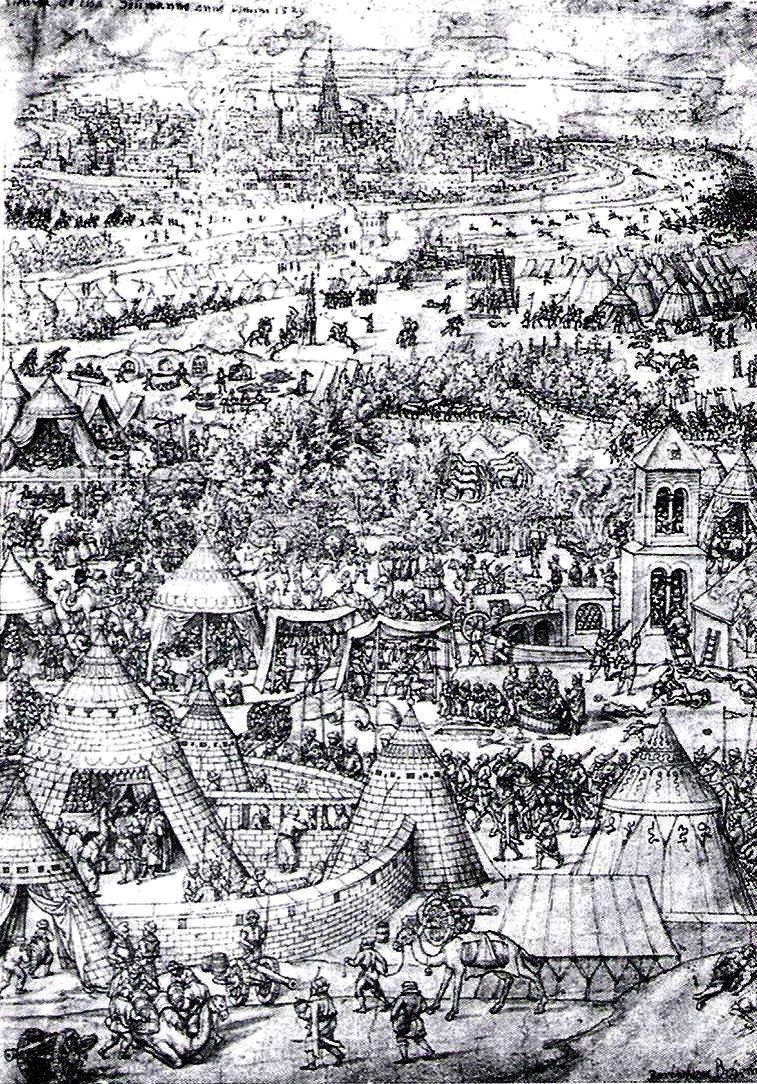

Siege of Vienna, 1526

In 1526 Suleiman the sultan invaded Europe marching from Constantinople to the Danube and gaining considerable success against the army of King Louis of Hungary. Much of his success was due to his massed use of artillery. Suleiman annexed the kingdom, and in view of this success embarked on a second invasion in 1529 with an army estimated at 120,000 troops and 20,000 baggage camels. Realizing that the medieval walls of Vienna targeted by the sultan were not impregnable, Ferdinand, the archduke of Austria, was determined to rely on his troops rather than masonry. His force was augmented by Spanish infantry sent by Charles from his army in Italy, and veteran German infantry regiments making up the remainder of his garrison of about 20,000.

Siege of Vienna, contemporary 1529 engraving of clashes between the Austrians and Ottomans outside Vienna by Bartel Behmam.

The Turks spread out on both sides of the Danube, but before they could move their 300 guns into position a sortie of 2,500 defenders inflicted a sharp defeat on advance posts. This blow was followed only three days later by a surprise attack of Spanish units which added to the casualties of the besieging forces. From this point onwards, the defenders continued to take away the initiative from their attackers at every opportunity. Ferdinand’s engineers proved so successful at counter-mining that many of the enemy’s mine-heads were detected and blown up before they could do any harm. Whenever a breach was opened, the garrison threw up new works while beating off the sultan’s storming parties. Finally a great Christian sortie of 8,000 men fell upon the invaders at dawn one morning with enormous destruction of Turkish troops and material. The adage that “the best defence is a vigorous attack”, has seldom been put to better effect.

As a last resort, Suleiman ordered a general storm of Vienna. His men, by now dispirited by the numerous past reverses, were unable to make any headway against the Spanish and German arquebuses. The assault failed with heavy losses, and that night the Ottoman host began a retreat which became one of the catastrophes of military history. Snow fell in October, weeks earlier than expected in the Danube country. Horses and camels floundered to their deaths in roads resembling morasses, while Austrian horsemen hung on the flanks of the beaten army to cut off stragglers. The sultan’s entire transport had to be burned, and most of his artillery was destroyed or captured before the shrunken remnant reached Constantinople in December. The outstanding defence of Vienna in 1529 may be considered the first great turning point in the struggle between Muslims and the Christian world. It did not deter Suleiman from conducting a third invasion in 1532, but this time he discretely avoided Vienna.

Siege of Vienna, 1683

Ottoman Siege of Vienna, 1683.

Well-placed and utilized artillery could often offset seemingly overwhelming numerical forces set against an opposing side. The lack of it could also change the tide in a siege where relief could arrive at any time. At the siege of Vienna in 1683, a coalition of Polish, German, and Austrian forces faced a much larger Turkish army of about 15,000 Tatars. The Turkish forces were led by a relatively unspectacular general, the Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa. From the month of March the Turks prepared to launch an attack on the Hapsburg capital of Vienna, and had gathered their forces together to conduct the advance fairly efficiently. By June, the Turks had invaded Austria, and on 14 July 1683, they reached Vienna, where they began to lay siege to the great city. The Turks were inadequately equipped with artillery, which caused the siege to drag out. Although the defenders resisted effectively, their food supply and ammunition stocks became depleted. As the siege wore on, the Turks managed to affect a number of breaches in Vienna’s walls but the barricades erected by the defenders hindered their efforts.

Siege of Vienna, 1683, painting.

In an early version of the NATO and Warsaw Pact treaties that were formed during the Cold War, Austrian King Jan III Sobieski (1674-1696) had signed the Treaty of Warsaw with the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold earlier that year on 31 March 1683. In the terms of the treaty, each of the co-signers agreed to come to the other’s aid if the Turks attacked either Krakow or Vienna. With the Turkish attack clearly underway, Sobieski proceeded to march to Vienna with an army of about 30,000 men, where he joined his forces with the Austrians and Germans. Sobieski launched a mounted attack against the weakest point in the Turkish lines, using his “husaria,” (Polish Hussars) on 13 September, completely surprising Kara Mustafa and causing heavy losses. It is claimed that this victory prevented Europe from being dominated by the Ottoman Turks and halted further invasions from their domain. It also secured Christianity as the main religion in Europe.[201]

Siege of Chittorgarh, 1567-1568

The City of Chittorgarh located in the State of Rajasthan in Western India, on the banks of river Gambhiri and Berach. Chittorgarh is home to the Chittor Fort, the largest fort in India and Asia. It was the site of three major sieges (1303, 1535 and 1567-1568) by Muslim invaders against its Hindu rulers who fought fiercely to maintain their independence. On more than one occasion, when faced with a certain defeat, the men fought to death while the women committed suicide by jauhar (mass self-immolation).

(Ssjoshi111 Photo)

Chittorgarh Fort. Originally called Chitrakuta, the Chittor Fort is said to have been built by Chitranga, a king of the local Maurya dynasty. The Guhila (Gahlot) ruler Bappa Rawal is said to have captured the fort in either 728 CE or 734 CE. In 1303, the Delhi Sultanate ruler Alauddin Khalji defeated the Guhila king Ratnasimha, and captured the fort. The fort was later captured by Hammir Singh, a king of the Sisodia branch of the Guhilas. Chittor gained prominence during the period of his successors, which included Rana Kumbha and Rana Sanga. In 1535, Bahadur Shah of Gujarat besieged and conquerd the fort. After he was driven away by the Mughal emperor Humayun, the Sisodias regained control of the fort. In 1567-68, the Mughal emperor Akbar besieged and captured the fort. (Paul E. Schellinger; Robert M. Salkin, eds. International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania, Routledge/Taylor & Francis, 1994)

Siege of Bijapur, 1686

On the 12th of September 1686, the Mughals under the command of Aurangzeb Alamgir conquered the great fort of Bijapur, thus ending the rule of the Adil Shahi dynasty.

(Yuvraj Chauhan Photo)

The legendary “Malik-i-Maidan” Gun is reported to be the largest piece of cast bronze ordnance in the world. The following inscription is engraved on the famous Malik-i-Maidan cannon: “There is one God, and no one besides him. In the 30th regnal year, equivalent to the year 1097 of the Hijra era, Shah Alamgir, the Ghazi, the Padshah who is the asylum of religion. He who administered justice and took the realm of kings”.

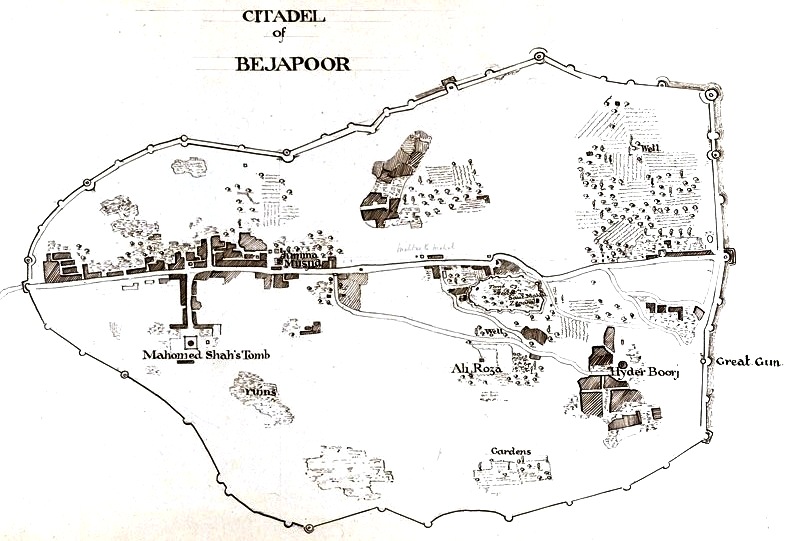

Map of Bijapur Fort.

The Siege of Bijapur began in March 1685 and ended in September 1686 with a Mughal victory. The siege began when the Aurangzeb dispatched his son Muhammad Azam Shah with a force of nearly 50,000 men to capture Bijapur Fort and defeat Sikander Adil Shah, the then ruler of Bijapur who refused to be a vassal of the Mughal Empire. The Siege of Bijapur was among the longest military engagements by the Mughals, lasting more than 15 months until Aurangzeb personally arrived to organize a victory.

In 1637, the young Prince Aurangzeb was the Subedar of Deccan, under the reign of his father the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan. He led a 25,000 strong Mughal Army to besiege Bijapur Fort and its ruler, Mohammed Adil Shah. The siege, however, was unsuccessful because the Adil Shahi dynasty sought peace with Shah Jahan, mainly through the cooperation of Dara Shikoh.

Ali Adil Shah II inherited a troubled kingdom. He had to face the onslaught of the Maratha led by Shivaji, who had fought and killed Afzal Khan, the most capable commander in the Bijapur Sultanate. The leaderless troops of Nijapur were consequently routed by Shivaji’s rebels. As a result, the Adil Shahi dynasty was greatly weakened mainly due to the rebellious Maratha, led by Shivaji and his son Sambhaji.

Sikandar Adil Shah was chosen to lead the Adil Shahi dynasty. He allied himself with Abdul Hasan Qutb Shah, and refused to become a vassal of the Mughal Empire. Angered by his refusal to submit to Mughal authority, Aurangzeb and the Mughal Empire declared war.

The Siege

In 1685, Aurangzeb dispatched his son Muhammad Azam Shah alongside Ruhullah Khan the Mir Bakshi (organizer) with a force of nearly 50,000 men to capture Bijapur Fort. The Mughal Army arrived at Bijapur in March 1685. Elite Mughal Sowars, led by Dilir Khan and Qasim Khan, surrounded and captured crucial positions around Bijapur Fort. After the encirclement was complete Prince Muhammad Azam Shah initiated siege operations by positioning guns around Bijapur Fort.

Bijapur Fort, however, was well-defended by 30,000 men led by Sikandar Adil Shah and his commander Sarza Khan. Attacks by Mughal gun batteries were repulsed by the large and heavy Bijapur guns such as the famous “Malik-i-Maidan“, which fired cannonballs 69-cm in diameter. Instead of capturing territories on open ground, the Mughals dug long trenches and carefully placed their artillery, but made no further advancements.

The Mughals could not cross through the 10-foot deep moat surrounding Bijapur Fort. Moreover, the 50-ft high 25-ft wide fine granite and lime mortar walls were almost impossible to breach. The situation for the Mughals worsened when Maratha forces led by Melgiri Pandit, under Maratha Emperor Sambhaji, blockaded food, gunpowder and weapon supplies arriving from the Mughal garrison at Solapur. The Mughals began to struggle on two front,s and became overburdened by the ongoing siege against Adil Shahi and the roving Maratha forces. Things worsened when a Bijapuri cannonball struck a Mughal gunpowder position causing a massive explosion into the trenches that killed 500 infantrymen.

In response to their hardships, Aurangzeb sent his son Shah Alam and his celebrated commander Abdullah Khan Bahadur Firuz Jang. Not wanting to permit the collapse of the Mughal Army outside Bijapur Fort, the Mughal commander Ghazi ud-Din Khan Feroze Jung I led a massive expeditionary reinforcement force to alleviate the hard-pressed Mughal Army, and drove out the Maratha forces. Abdullah Khan Bahadur Firuz Jang, a highly experienced Mughal commander positioned at the outpost of Rasulpur, routed a 6,000-strong infantry contingent led by Pam Naik, which had intended to carry supplies to Bijapur Fort during a night attack.

The Mughals regained control of the supply routes leading to Solapur, but no successful advancement was made into Bijapur Fort. The lengthy siege turned into a stalemate. Aurangzeb therefore personally gathered a massive army in July 1686 and marched slowly towards Bijapur Fort. On his arrival outside Bijapur Fort, he established encampments beside Abdullah Khan Bahadur Firuz Jang on 4 September 1686. Aurangzeb personally rode out inspiring his army of almost a 100,000 men to begin a full-scale assault. After eight days of intense fighting, the Mughals had successfully damaged the five gates of Bijapur Fort and collapsed substantial portions of the fortified walls, thus enabling them to breach the moat and conquer the city. They captured Sikandar Adil Shah and bound him in silver chains before presneting him to Aurangzeb.

Aftermath

Sikandar Adil Shah had suffered many wounds and ultimately died on 12 September 1686, resulting in the end of the Adil Shahi dynasty. Aurangzeb then appointed Syed Mian (father of the Sayyid brothers) as the first Mughal Subedar of Bijapur.

The Mughals had annexed and conquered a weakened Bijapur, but their control of the region began to weaken after the death of Bahadur Shah I in 1712. The Nawabs in the region declared their independence after a few decades. Eventually, after 1753, the Marathas occupied much of Bijapur. (Hugh Chisholm, Editor, Bijapur. Encyclopaedia Britiannica (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, 1911)

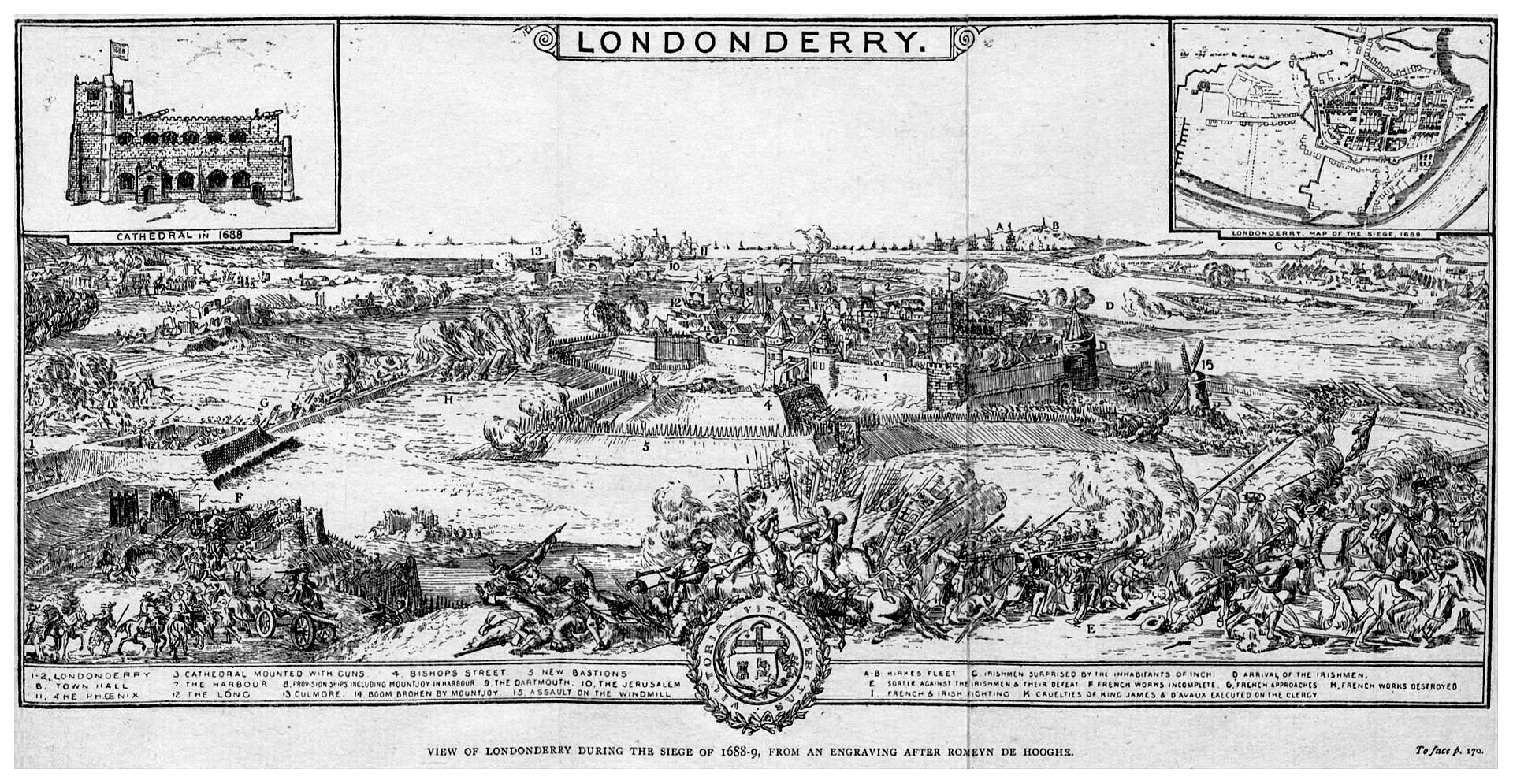

Siege of Londonderry, 1688

In December 1688, the town of Londonderry (also known as Derry) declared its gates closed to James II, then fighting to regain the throne of England that he had lost in the ‘Glorious Revolution’, a bloodless coup d’etat in which William of Orange had been invited to become king.

On 13 April 1689 James came to the gates of Londonderry and called on the city to surrender. But thirteen apprentice boys ran to the city gates and shut them in the face of his army.

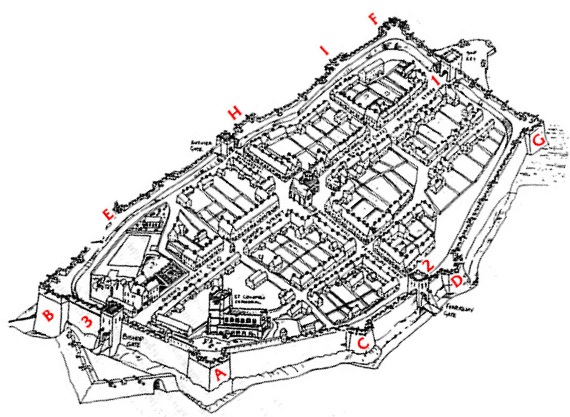

Londonderry fortification diagram showing the 17th century walls.

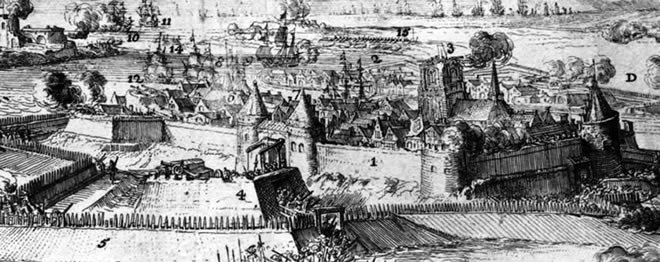

Londonderry, oblique view engraving from the era of the sieges.

A siege began which lasted until 28 July, a total of 105 days. It was a brutal affair, fully in keeping with the standards of seventeenth century warfare. Thousands died as James’s army rained down cannon balls and mortars on the town. Disease and famine also took a terrible toll, among the attacking soldiers as well as the townsfolk. Eventually, an English ship called the Mountjoy managed to break through a boom which had been set up across the river Foyle by the besieging army and relieved the town.

The armed merchant ships Mountjoy and Phoenix break through the defensive boom to relieve the Siege of Derry. (James Grant)

Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, Seigneur de Vauban and later Marquis de Vauban (1 May 1633 – 30 March 1707)

Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, a Marshal in the army of Louis XIV, was a member of the French bourgeoisie who made important contributions to the field of engineering and in the application of science to warfare. Vauban devised a method of siege that involved a geometric advancement of trenchworks and approaches that moved from parallel to parallel against enemy fortifications that was highly successful. The widespread adoption of his practical solutions to the problems of siege warfare resulted in a remarkable order by Louis XIV to commanders of all French fortifications. The king ruled that should a fortress commander come under attack by an enemy using Vauban’s methods of siege, the commander might honorably surrender once an initial breach had been made in his citadel and he had repulsed one assault.[202] In effect, Vauban’s methods of siegecraft virtually guaranteed the successful completion of an assault on the defense-works and fortifications in existence at that time, and indeed for many years to follow after his death.[203]

The sciences of artillery ballistics and the design of fortifications that could withstand artillery projectiles had both been making rapid advances. Artillery had long since negated the existing defenses of the old high-walled medieval castles that had been designed to withstand early siege methods. Fortress design had become highly standardized. Low-silhouette gun platforms would be laid out to conform to the conventional pattern of a polygonal bastion. The bastions would in turn be adapted to the contours of the terrain and the dimensions of the site to be defended. Heavy inner ramparts were designed into fortifications, with a parapet for the mounting of additional guns. A broad ditch would be dug outside the walls, followed by the construction of an outer rampart called a “glacis.” This would consist of a wall with an open, gentle slope up which an attacking force would have to advance while being continuously exposed to the defenders fire. The key element in the layout of these fortifications, consisted in the positioning of outlying bastions. These were designed so that they placed every potential axis of attack not only under direct fire, but also under mutually supporting crossfire. The design of the bastions had therefore come to be a matter of applying standard geometric rules, formulated largely by Blaise, Comte de Pagan, who was a mathematical theorist rather than a practicing engineer.[204]

Blaise François, Comte de Pagan, engraving. (Charles Perrault, Les Hommes illustres qui ont paru en France pendant ce siècle, Paris, 1696)

Although Vauban studied and made use of Pagan’s idea’s, he proceeded to develop several specific and separate ideas of his own in his designs of fortifications. One of these was to build ramparts of earth rather than of stone. He had sound reasons for this, based on his personal observation of cannon-fire. Stone ramparts shattered stone cannonballs, causing them to break-up and shoot off dangerous fragments. Earth walls, which could absorb the impact of incoming rounds, were therefore safer, and had the added advantages of being cheaper and more easily built. Secondly, he designed angled rather than rounded bastions, therefore making it possible for all parts of defended walls to be covered by enfilade fire against attackers. These ideas had already been applied to some extent in the wars since the mid-sixteenth century, but no one thus far had thought them out and applied them to their fullest extent. Vauban’s methods transformed this branch of warfare into a geometric exercise, with the result that his defenses eventually became too formidable to allow frontal assaults by irreplaceable soldiers. In a logical extension of his methods, he always made the best use of the ground to assist and expand the depth of his defensive network.[205]

Vauban adhered to simple basic principles in his fortifications, but followed no set design.[206] He retained the traditional ground plan for a fortress, which consisted of an inner enclosure, a rampart, a moat and an outer rampart. Existing fortresses could last intact only until the main body of their fortifications had been breached, and the result of a siege was thus in large part a question of which side could hold out the longest. To counter this problem, Vauban endeavored to extend the fortification of his outworks as far as possible. He thus compelled the enemy to begin his siege operations at a distance, and multiplied the obstacles in his way so that the difficulties in gaining ground never ceased. If the outworks should fall to the enemy, they were still commanded by fire from the main central works.[207]

Vauban’s geometrical skill and practical eye for ground enabled him to design fortifications in such a way that every wall facing outwards was flanked and supported by additional works behind and beside it. The basic element in these designs, multiplied and varied in scale, was a large outward-pointing triangle with its inner side missing.[208] The outward point made a difficult target for the enemy to breach and thus forced him to concentrate his forces vulnerably. Each outward-facing wall of the triangle was so angled as to cover the area of wall between it and the face of the next salient (a piece of land or section of fortification that juts out to form an angle). This was the principle of the great bastions on every angle of the main polygon. The large bastions were interspersed with smaller ones along the curtain wall, close enough together for each to be able to cover the next with small-arms fire. Other triangles, widely varying in size, called “ravelins,” (a triangular fortification or detached outwork, located in front of the innerworks of a fortress), or “demi-lunes” (half-moons), if they were actually crescent shaped, stood in a dry moat. The demi-lunes projected farther forward in such a manner that they covered each other, as well as being covered from behind. Repeated complexes of fortifications of this type often extended 300 yards from the central rampart, and made powerful obstacles to a siege.[209]

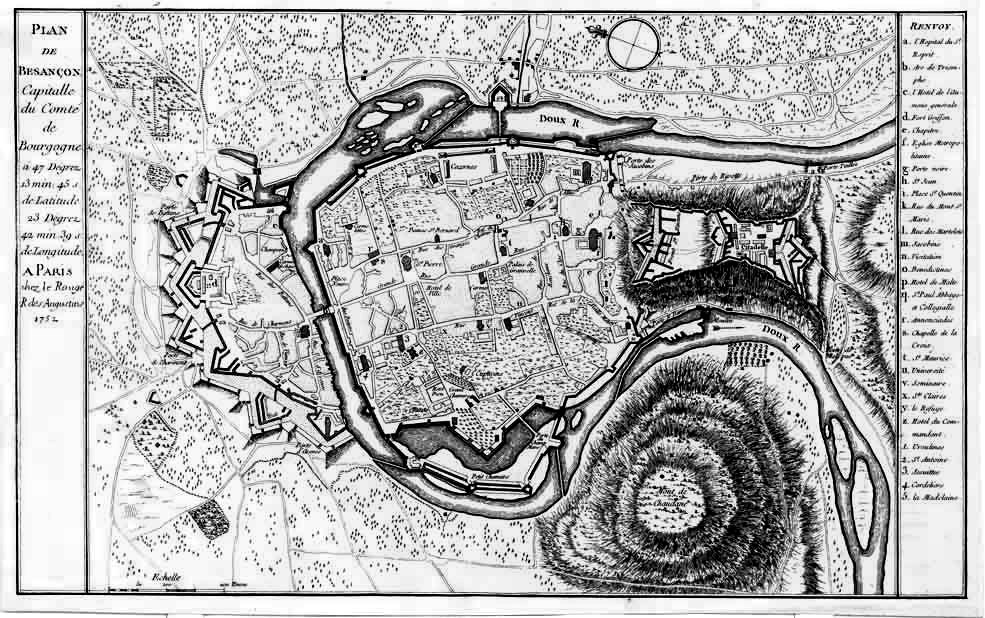

The forts designed by Vauban for Louis XIV have come to be divided by historians into three stages of development. An examination of specific details found in several key fortresses of his design follows, including Lille, Arras, Besançon, Belfort, Landau, Neuf Brisach and Louisbourg.

Besançon fortifications designed by Vauban.

(Photo du comité régional du tourisme de Franche Comté)

Citadel of Besançon, fortifications designed by Vauban. This 17th-century fortress stands in Franche-Comté, France. It is one of the finest masterpieces of military architecture designed by Vauban. The Citadel occupies 11 hectares (27 acres) on Mount Saint-Etienne, one of the seven hills that protect Besançon, the capital of Franche-Comté. Mount Saint-Etienne occupies the neck of an oxbow formed by the river Doubs, giving the site a strategic importance that Julius Caesar recognised as early as 58 BC. The Citadel overlooks the old quarter of the city, which is located within the oxbow, and has views of the city and its surroundings.

Vauban’s first system was essentially the same as that devised by Blaise Françoise, Comte de Pagan (1604-1665), who was another practical soldier with an equally remarkable career. In spite of having been blinded in battle, Pagan achieved the rank of Maréchal-de-Camp, as well as having written a book advocating a new order in which works should be constructed. In Pagan’s opinion the bastions were the most important features against which the main force of an attack would fall, and therefore the integrity of this work depended on its being sited correctly. Once the works had been sited they could then be connected by ramparts in such a way as to give whatever space was necessary inside the walls, and not inside the bastion salients. Pagan strengthened his works by fortifying outwards. He later proposed a second method in which he converted the ravelins and counterguards into a continuous protective envelope around the work, echoing the bastioned shape and furnished with three-tier batteries at every flanking angle. A second wet ditch was placed in front of this envelope, protected by more ravelins and then the usual covered way and glacis. The only fortress in existence today attributable to Pagan is that of Blaye, on the Gironde. Construction of Blaye according to Pagan’s designs began in 1652 and was completed in 1685 by Vauban, thus forming an interesting link between two successive masters.[210] The major modifications that were to make Vauban the most renowned of military engineers came late in his career, after he had already constructed most of his fortresses.

(Eremeev Photo)

Ravelin Peter (1708) and access bridge, Petersberg Citadel, Erfurt, Germany.

(Author Photo)

Entrance to Petersberg Citadel, Erfurt, Germany.

Blaye Citadel, plan view, 1752.

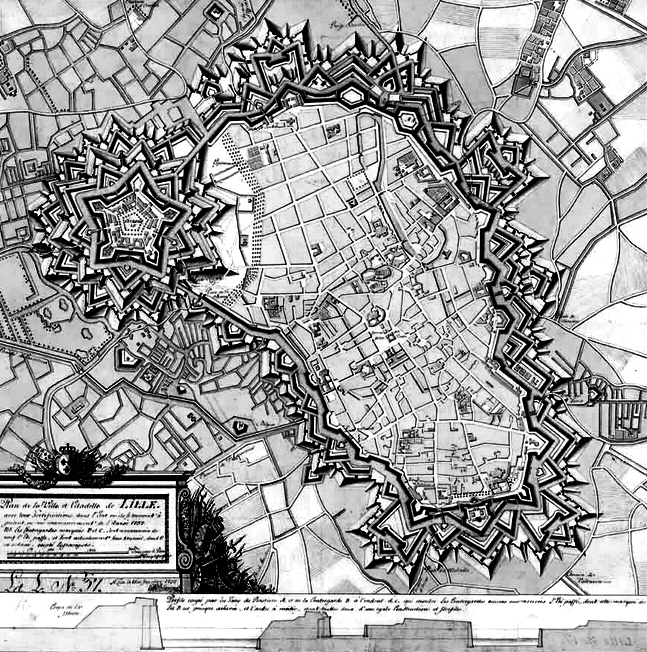

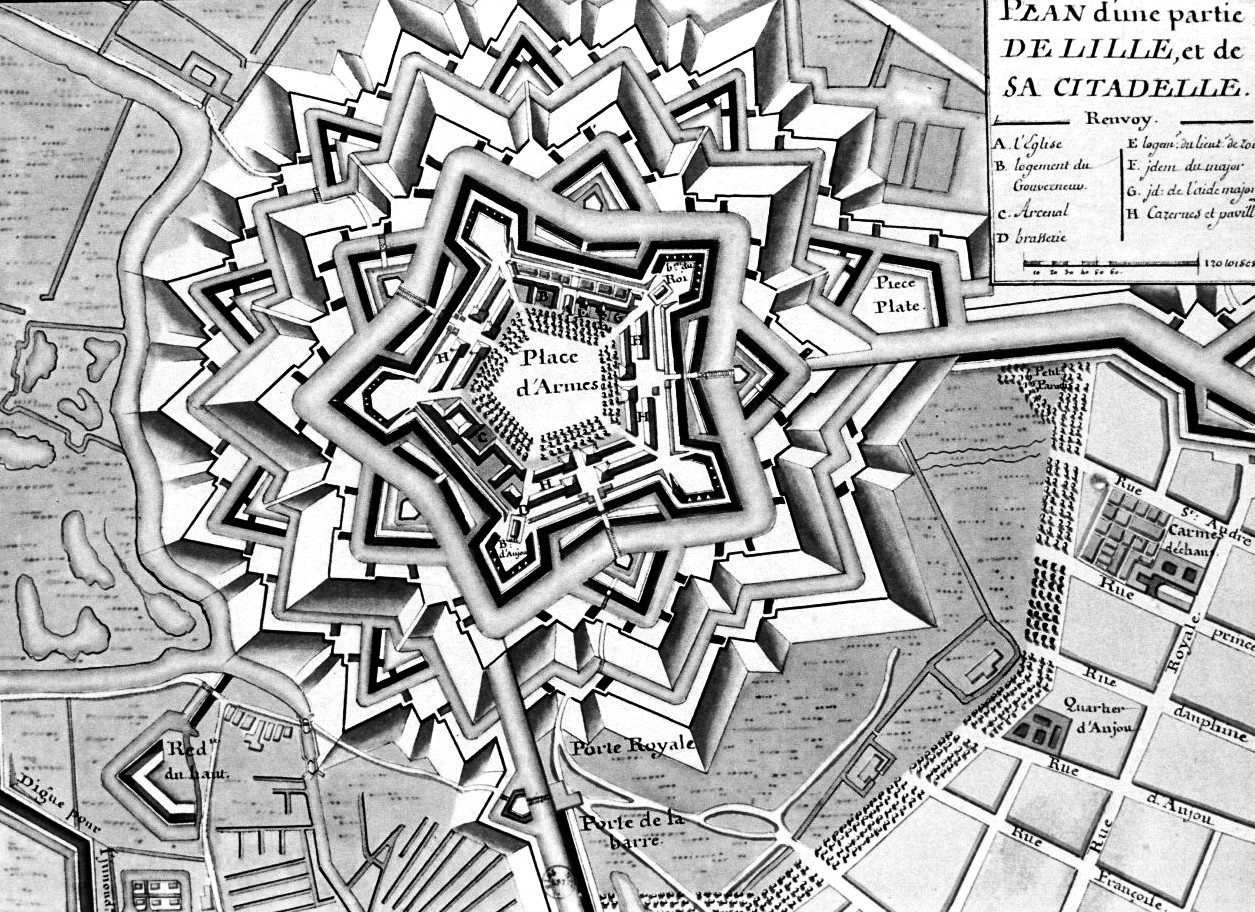

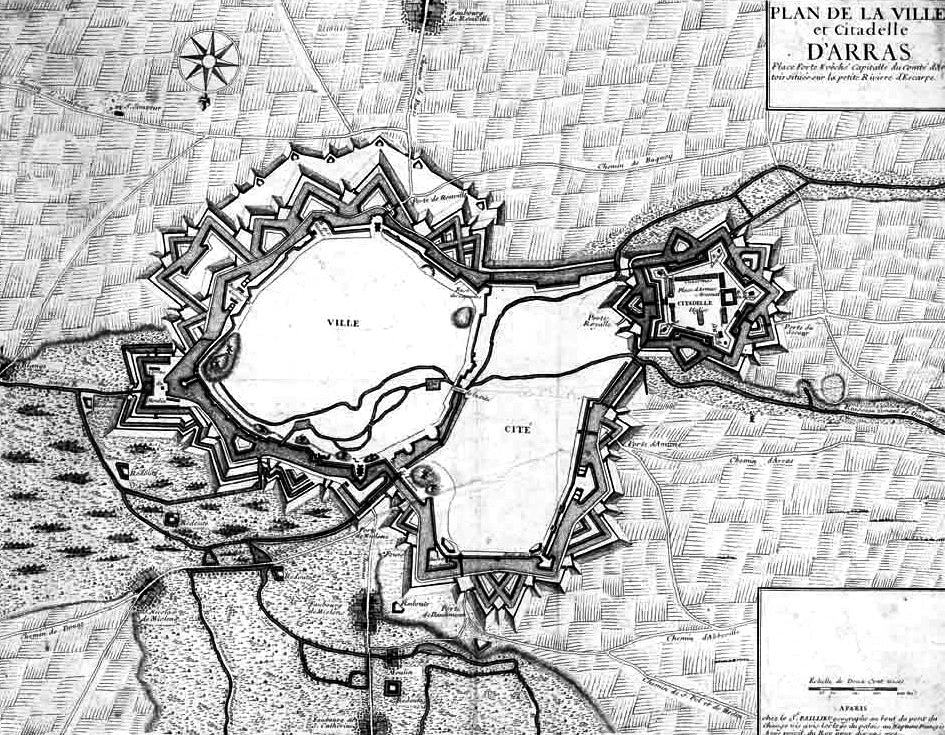

When French forces seized Flanders in 1667, the situation created the necessity to strengthen fortifications or add citadels at strategic places in, or adjacent to, the disputed territory. The citadels at Arras and Lille were thus the first major projects undertaken by Vauban, along with the strengthening of other town fortifications.[211] The resulting construction produced specific and identifiable elements that were to characterize most of his later fortifications.[212] Lille, however, was highly regarded as one of the engineer’s finest works, a classic example of a “bastioned” defence.[213]

The fortification of Lille, France, designed by Vauban in 1709.

The Citadel of Lille, detailed view, designed by Vauban in 1709.

As an example of Vauban’s “first” system, the citadel of Lille was laid out on a perfect pentagon, each front (measured from one flanked angle to the next), being 300 metres long and the curtains between bastions being half that length. The bastions are large and spacious, with straight flanks set at an obtuse angle (106 degrees) to the curtains in accordance with Pagan’s concepts. There are no right angles to be seen in the fortification.[214] The outworks Vauban placed in the ditch before the curtains were an innovation of his. Instead of the “fausse-braye” so widely favored at the time, he introduced a variant he called a “tenaille.”

Vauban’s tenaille was a low, parapetted work built along the prolongation of the lines of defence works from the faces of the adjacent bastions and which formed a re-entrant angle where the lines intersected midway along the curtain. The resulting defence works thus presented an obstacle in the form of a shallow V in front of the curtain, so that an enemy gaining the “covered way” of the glacis would find an additional area behind which the defence could continue a spirited resistance with small arms. In addition, the work masked the base of the curtain and adjacent flanks from enemy batteries. The function of the tenaille was essentially the same as that of the fausse-braie, but Vauban had detached these works from the base of the rampart and advanced them into the ditch, aligning them along the line of defence. He thereby achieved more efficient flanking fire, as defenders would be augmenting the fire from the faces of the adjacent bastions instead of simply firing straight out from the curtain. At the same time, he lessened the likelihood of debris from the parapets on the main “enceinte” collapsing onto the heads of the defenders below after an artillery strike. Vauban was convinced of the utility of additional defence in this location, and situated tenailles of one form or another in all of his fortresses whenever possible.[215]

Vauban’s use of defence in depth was well advanced even in his earliest fortifications, when he endeavored to present to the enemy a series of obstacles, each of which had to be overcome in turn before reaching the main body of the place under attack. At Lille for example, the “practitioner” initially placed a “demi-lune” on each front before the tenaille and the curtain. For greater resistance, each demi-lune contained in its gorge a redoubt (a fort or fort system usually consisting of an enclosed defensive emplacement outside a larger fort, usually relying on earthworks, although some are constructed of stone or brick), separated from the larger work by a small branch of the ditch. In addition, beyond the 40-metre wide flooded ditch and the glacis, he added another wet ditch. In the re-entrants of this advanced ditch on all fronts except the two covered by the town itself, were placed seven small demi-lunes or lunettes (a half-moon shaped space, either filled with recessed masonry or void), in total. Finally, an additional covered way and glacis encircled the entire site.[216]

Vauban surveyed the site not only from the point of view of an engineer, but from his observations as a soldier of what might work and what did not. For the main enceinte for example, he calculated that an escarp inclined to a “batter” of one in five would retain the 12-metre high earthen rampart if counterforts spaced at 18 pieds (5.8 metres) were used and the top of the escarp was 4 1/2 pieds (1.4 metres) thick. The base of the wall, the angles and the cordon were all in dressed stone, as were the gateways. The revetments were all in brick. In the interior, the buildings were similarly furnished with dressed stone surrounds and brick walls. From the parapets, the defence commanded the tenailles, demi-lunes, covered ways and glacis. From the tenailles, the ditch, covered way and the rear of the demi-lunes could be swept. From the demi-lunes, fire could be directed into the advanced works. In reverse, however, each successive work masked the next, so that only the parapet of the main enceinte was visible. Lille therefore exemplifies Vauban’s concerns with the practical aspects of construction of his fortifications.[217]

The citadel of Lille was built on a site never previously used for fortifications, in an area of perfectly flat, open ground, permitting a “textbook symmetry” rarely found in Vauban’s works. Regular fortifications were held to be preferable, as they were equally strong all around. Engineers however, would more often than not be confronted with an existing enceinte to be strengthened or unfavorable terrain to be fortified. Simple geometry was not enough in situations that were by definition, exceptions to the rules. This problem was not new to Vauban, and he knew that his predecessor Pagan also had to deal extensively with designs for irregular fortifications.[218]

Vauban’s methods were not only developed from Pagan’s principles, but expanded upon whenever the opportunity presented itself. For example, in designing the new defenses for the town of Ath, similar dispositions of “fronts” to those of Lille were employed, using six sides of an irregular heptagon. On the seventh side, however, he imposed a modification on the existing town and walls. The straight curtain in which the medieval castle was set was too long to be treated as a single front, so Vauban constructed a flat bastion around the castle midway along the curtain wall. An outer ditch was added to the front of this wall, and a horn-work was added to cover a potential weak point where the River Dendre entered the town.[219]

During this same period, Vauban built the citadel at Arras and improved the town’s defenses. The most striking difference between Lille and Arras is that, in Arras, he designed his bastions with orillons and retired flanks.[220]

The Citadel of Arras, plan view of the fortifications designed by Vauban.

Vauban made liberal use of orillons throughout his fortifications for the next 20 years following the design of Lille and Arras, but only rarely used casemates, and then only under exceptional circumstances. He instead designed solid retired flanks that permitted artillery fire from the parapet level only. Such flanks were built on a graceful arc that permitted the defenders more room to maneuver. In order to gain additional room, Vauban modified his design of the curtain wall without leaving a continuous straight line to directly join the flank. Instead, a short distance before the junction, he angled the curtain slightly back. This break or “brisure” kept the entire curve of the flank unobstructed. It has been said (by Muller) that this was Vauban’s only original design element. Vauban may have been influenced in this by Pagan, since he later completed Pagan’s citadel of Blaye where curved flanks are in evidence. Whatever the inspiration, Vauban rapidly introduced this design (in the true style of a sound practitioner), on all the frontier strongholds of France, and it is therefore the one most readily identified with the great engineer.[221] There are still several well-preserved partial fronts designed by Vauban in existence.[222] Many of Vauban’s fortresses still stand, and are a visible reminder of the lasting qualities that helped to make his fortresses as nearly impregnable as the engineering of the age would allow.[223]

It is difficult to get an exact figure for the number of fortresses connected with Vauban’s name, as the figures vary from author to author. Dupuy, for example, has stated that Vauban built 33 new fortresses, and remodeled 300 others. Goetz and Hogg have both indicated that he worked on 160, and Koch states that Vauban built 90 fortresses.[224] All those that are presently associated with this remarkable engineer however, have been constructed on the basis of precise mathematical calculations and usually contain a practical layout of depots, arsenals and storage of supplies which would in turn provide a very secure base for offensive operations.[225]

The second of Vauban’s systems began to appear in 1682, and was used for the first time at Belfort and then later at Besançon. Being a practical engineer, Vauban took note of deficiencies in his first system and improved on it. The second system was therefore devised in a logical and practical extension of the first. He retained the use of a basic polygon structure, but the curtain walls in the regions between the bastions were lengthened. The bastions themselves were replaced at both sites by a small work or tower at the angles, these in turn being covered by so-called detached bastions constructed in the ditch.[226]

Before the innovation of Vauban’s second system, the outlying bastions all remained attachments of the main enclosure, or the “main enceinte.” If any of them fell, the citadel itself was immediately threatened. Vauban’s replacement of the bastions at the angles of the polygon with these small works or towers that were themselves covered by detached bastions, forced an assailant to work his way through them. Even then, an attacker would still not be in a position to threaten the principal defensive works.[227]

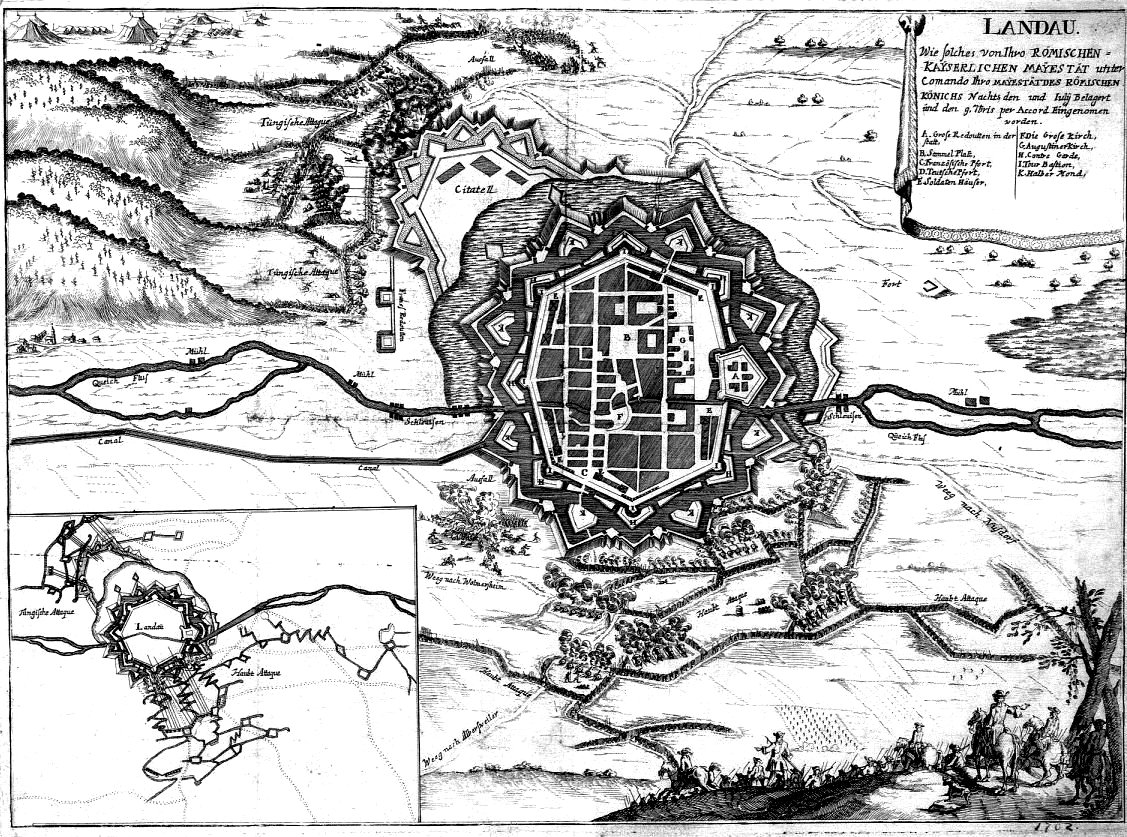

Another fortress most commonly classified as belonging to Vauban’s second system is that of Landau, which is comparable in size and scope to Belfort. The most striking characteristic of both of these fortresses is the fragmentation of the design of the enceinte. Small masonry gun towers or “tours bastionnes” project from the curtain walls, while expansive faces and flanks that typify Vauban’s bastions have been detached from the enceinte and placed before the towers. This design is somewhat like the face-covers or counterguards Pagan had originally proposed. The size of these works, together with the fact that they were designed with true flanks, resulted in their being referred to as “bastions detacheés,” or “bastions a contregarde,” rather than face-covers.

The problem of commanding heights is of fundamental concern to all military engineers and throughout his career, Vauban made masterly use of heights when attacking a place. Vauban fortified places in mountainous districts such as Mont Louis in the Pyrenees, Briançon, and Mont Dauphin and Château Queyras on the Savoy frontier.[228] He also made every attempt to minimize the danger when fortifying places where he had no choice in the selection of the terrain.[229] Concerning hill fortifications, Vauban commented for example, that “the frontier of the Savoy was so extremely hilly that I was obliged to invent a new system of fortifications so to take advantage of it.” He also mentioned Colmar, Entrevaux and Guillames as being “situated in hilly country and commanded from far and near by surrounding high ground, (and therefore) only the method of fortifying with tower bastions should be followed.” He used “tours bastionneés” in the Alpine region, for example, but developed a completely different arrangement in the Pyrenees.

In the valley of the Tet, on the route from Roussillon to the pass into Spain, lies the formerly Spanish town of Ville-franche-de-Conflènt, fortified since medieval times and improved by Vauban after his inspection in 1669. Describing the place, he wrote that it was “tightly hemmed in by surrounding high mountains with steep slopes so close that even the most distant was within sling-shot”, but because of the sharp inclines and extreme height of the mountains, no artillery could be brought to bear. However, outcrops afforded “positions for musketry, from which anyone showing his nose in the streets could be picked off like a sitting duck.”

(Makinal Photo)

Ville-franche-de-Conflènt, view of the town from Fort Liberia. The original town dates from 1098, and was fortified because of its strategic position in lands that changed hands between French and Spanish occupation. In 1374, Villefranche resisted the siege of Jaume III the son of last King of majorca. In July 1654, the French captured the city after eight days, and the troops of Louis XIV took Puigcerda from the Spaniards. The town was part of the program of construction and improvement of outlying French defences through 1707 by Marshla Vauban.

To afford adequate protection for the defenders of fortifications in hilly terrain, Vauban ensured that normally exposed parapets were roofed over in the most vulnerable sectors, so that bastions and curtains assumed the appearance of a medieval “chemin de ronde,” or covered street. At the Northeast angle of the town of Ville-franche-de-Conflènt for example, the parapets of the Bastion du Roi were extremely high in relation to the terreplein they covered. This gave the gunners manning the embrasures maximum protection. Masonry traverses bisecting the bastions were included to reduce the risk of enfilading fire sweeping across one flank and taking defenders of the other flank in the rear. This worked well in this fortress, but Vauban did not repeat the idea in any others.[230]

(A1AA1A Photo)

Ville-franche-de-Conflènt fortification.

Vauban continued to make further revolutionary improvements to his method of defence in depth. In all previous cases, adaptation of fortifications to mountainous terrain had been through projecting crown works or horn works, and when this was done, the main line was directly affected. Vauban gained flexibility by adapting his designs to the terrain without imperiling the main line of defence.[231]

Fortress of Belfort, plan view of the fortifications designed by Vauban.

The fortresses of Belfort and Landau both used towers and detached bastions to replace the conventional bastions. Tower bastions were actually first introduced when they were added to the existing enceinte at Besançon, years earlier. There, and at Villefranche, Vauban’s task was to improve the existing defenses of a town. Its medieval walls were built on the river’s edge, and were within range of commanding heights. On the limited ground available on two fronts, squat, compact artillery towers were built.

One of the criticisms of Vauban’s tower bastions was that they were too vulnerable to artillery fire. The towers at Besançon were commanded by heights that Vauban was careful to fortify, but if these had fallen into enemy hands, the towers could have been bombarded with ease. It is therefore unlikely that Vauban the practitioner considered his towers as offering improved defence against artillery, and thus the local constraints at Besançon may have been the immediate reason behind his new approach. Although the situation at Villefranche was better since artillery could not readily be brought into action except in the pass, Vauban would likely have employed tower and detached bastions had he considered them effective alternatives to standard bastions at the time.[232]

Fortress of Landau, plan view of the fortifications designed by Vauban. This fortress came under siege in 1702.

After the construction at Besançon, Vauban favored further experimentation along the same lines. At Belfort, the limitations on design are less apparent, and could have been resolved by a series of strong outworks such as he had already used at Arras or Bayonne. The change in approach is even more marked in the defences of Landau, where clear details of Vauban’s second system can be seen in the plan of the fortress, such as his use of tower bastions on the main enceinte protected by detached bastions or counter-guards. The intervening tenailles cover the curtains, which rise from a wet ditch. Demi-lunes are located in advance of the tenailles on all fronts, and a wet outer ditch surrounds the place at the foot of the glacis. Two large horn-works in the conventional manner with fronts comprised of two half-bastions with orillons and retired, curving flanks are located south of the town. An additional outer perimeter of detached redoubts was placed beyond the glacis, as discovered by attacking forces during four sieges made on the site during the War of Spanish Succession. These works, shaped like demi-lunes and open at the rear so that they would be exposed to defensive fire if taken by the enemy, demonstrate Vauban’s increased preoccupation with defence in depth. Here again, he deliberately placed as many obstacles in series in the way of an attacker, well before the main body of the fort could be reached. It has also been suggested by the engineer Lazard, that Vauban developed his second system as a means of countering the effects of ricochet fire.[233]

Vauban’s unconventional designs were not entirely impregnable, in spite of the strengths of the bastioned system of fortification. Landau for example, changed hands often during the War of the Spanish Succession, being taken by the Allies in 1702, recaptured by the French in 1703, taken again by the Allies in 1704, and finally recaptured by the French in 1703. These battles demonstrated that no fortress or system could be considered impregnable, and Vauban’s successors did not attempt to emulate his second or third systems. He had, however, spent a lifetime providing the country with a formidable barrier of fortresses along every frontier and exposed coastline, a barrier that, in spite of all the wars, had held. It was thanks to the holding power of Vauban’s fortifications (and to the generalship of Villars), that France secured very reasonable terms at the final Treaty of Utrecht in 1713.[234] When peace came, the French frontiers were still secure.[235]

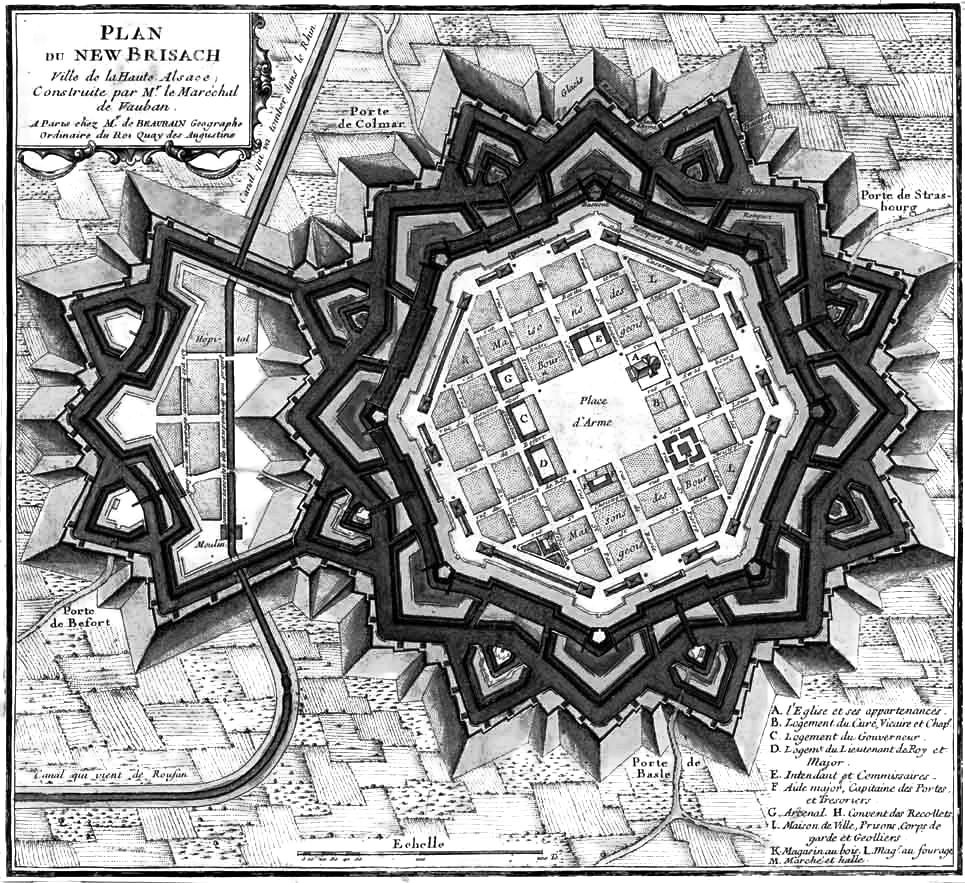

Neuf Brisach, France, plan view of the fortifications desinged by Vauban.

(Luftfahrer Photo)

Neuf Brisach, France, aerial view.

Neuf Brisach was intended to guard the border between France and the Holy Roman Empire, subsequently the German states. It was built after the Treasty of Ryswick, in 1697, that resulted in France losing the town of Brisach, on the opposite bank of the Rhine. The town’s name means New Breisach.

Vauban’s third system consists in fact, of a single fortress, that of Neuf-Breisach in Alsace. It was designed in 1697, and not completed until 1708, a year after Vauban’s death. It was the last major work he designed, and although he used the same basic principles introduced at Belfort and Landau, the practitioner side of him led him to the increase the scale of almost all elements of this major new fortress. Everything was made larger than in his previous designs, including the towers, or “tours bastionées” at the angles of the fortress, covered by detached bastions.[236]

In this scheme the curtain is modified in shape to permit an increased use of cannon in defence, and the towers, the detached bastions, and demi-lunes are all increased in size.[237] The differences are in detail only, an additional flank being provided on the curtains by adding re-entrant angles. In plan, the enceinte gives the appearance of a series of shallow bastions with the towers located at the flanked angles. Casemates were provided in the small flanks thus created. The demi-lunes were made stronger by the inclusion of a detached redoubt in each gorge. In profile, the counter-guards or detached bastions are seen to be demi-riveted. The masonry escarp is only as high as the level of the covered way. The rampart above is of sloped earth with a line of pickets and a quickset hedge at the foot of the slope. Detached works beyond the glacis are absent and none were needed.[238]

Neuf Breisach was an entirely new place, built on the flat, open land that was the old floodplain of the Rhine River. Vauban selected the site at some distance from the river in order to keep the fort out of range of guns on the higher ground of Alt-Brisach. Vauban had submitted three schemes to the King, who after close study approved the third one. This design provided an octagon fort with bastioned towers in the angles, detached bastions, tenailles, demi-lunes, and with a moat filled from the Rhine. (The estimated cost was 4,048,875 livres, and it was not completed until 1708).[239] No earlier defenses had to be considered, nor were any constraints imposed by the lie of the land. All of the experience and expertise at Vauban’s disposal were given free reign in the layout and design of his third system. Defence in depth and the formidable array of barriers at Neuf Breisach were the culminating result.[240]

In essence, the third system was only a modification of the second. Although it was used for only a single work, Neuf-Breisach is considered the great masterpiece of Vauban.[241] This should be considered from the point of view that during a half century of ceaseless effort, Vauban conducted nearly fifty sieges and drew the plans for well over a hundred fortresses and harbor installations. For example, during the interval between the cessation of French hostilities with Spain in 1659 and Louis XIV’s first “War of Conquest” in 1667, Vauban worked to repair and improve numerous fortifications of the kingdom under the direction of Clerville.

The War of Devolution (1667–68) saw the French armies of Louis XIV overrun the Habsburg-controlled Spanish Netherlands and the Free County of Burgundy, only to be pressured to give most of it back by a Triple Alliance of England, Sweden and the Dutch Republic, in the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle. The painting by Charles Le Brun shows Louis XIV visiting a trench during the war.

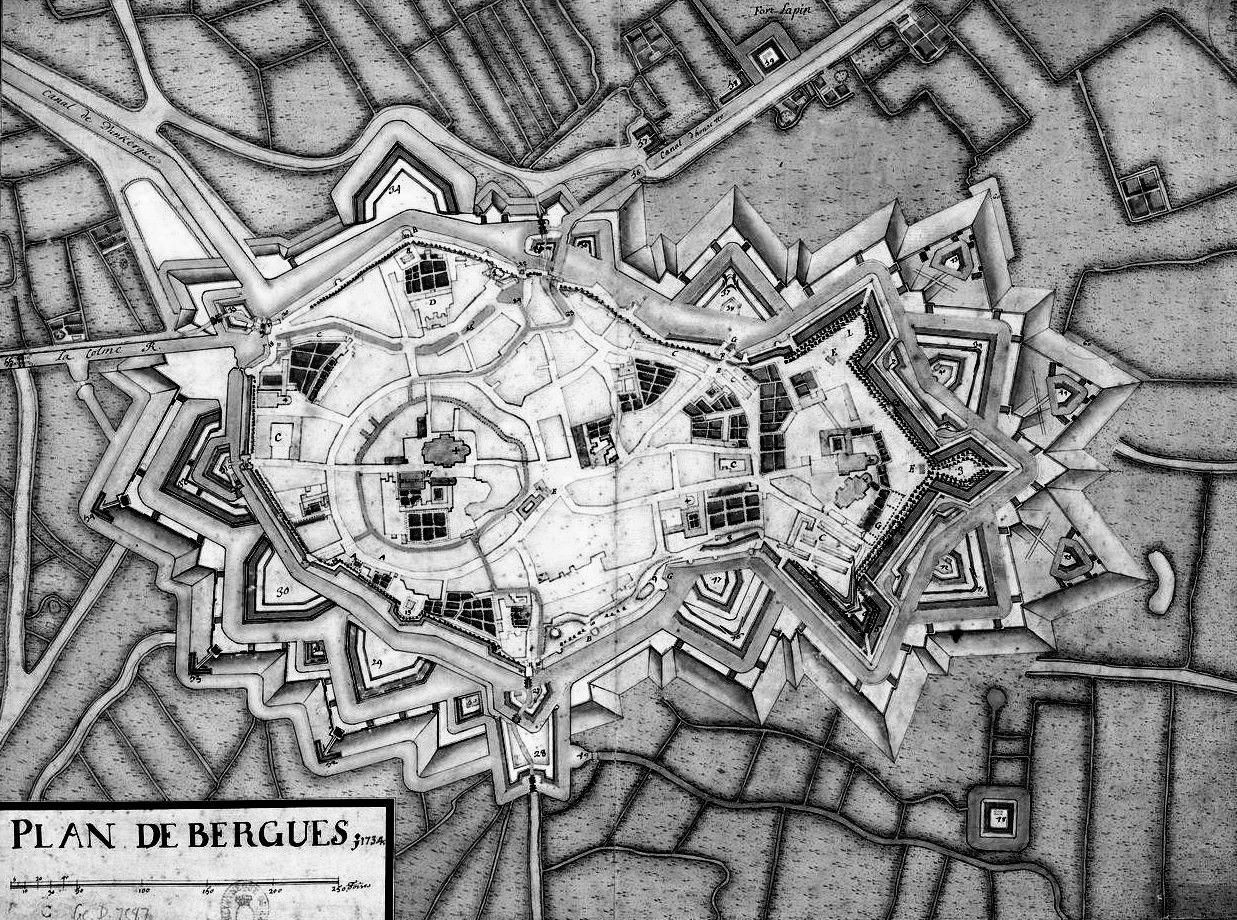

In 1667 Louis XIV attacked the Low Countries. It was during this brief “War of Devolution”, that Vauban so distinguished himself as a “master of siegecraft” and the other branches of his trade that Louvois noticed his distinct superiority to Clerville and made him virtual director, as commissaire general, of all the engineering work in his department. The acquisitions of the War of Devolution launched Vauban on his great building program. Important towns in Hainaut and Flanders were acquired, including Bergues, Furnes, Tournai, and Lille. These and many other important positions were then fortified according to one of the three systems developed by Vauban.[242]

Vauban’s systems of fortification evolved from his experience on the battlefield, and from the exercise of considerable common sense. The systems attributed to Vauban were categorized on the basis of regular fortifications, although the majority of Vauban’s works, adapted as they were to the terrain, were highly irregular.[243] He did not reinvent the wheel if it wasn’t necessary, and as noted, his first system was primarily based on a trace originally designed by Pagan, almost without modification. The outlines of these early fortification designs were, whenever possible, regular polygons, i.e.: octagonal, quadrangular, and even roughly triangular, as at Kenoque.

Bastions were still the key to the defensive system, though they tended to be smaller than those of Vauban’s predecessors. Except for the improvements of detail and the greater use of detached exterior defenses, little had altered since the days of Pagan.[244] All works with recognizable bastions, whether having straight flanks or curved one with orillons, were classed in the first system. Within this system, considerable variances in the lengths of fronts, curtains, faces and flanks occur according to the dictates of the terrain. Vauban did not decree specific dimensions. The same holds true for the plans in profile, as the low, earth-topped, tree lined ramparts as seen in the fortress at Bergues, are adapted to the flat, inundated meadowlands of the Low Countries and bear no resemblance to the multi-tiered effect created by the defenses of the citadel at Besançon, in the foothills of the Jura.[245]

Fortress of Bergues, plan view of the fortifications designed by Vauban.

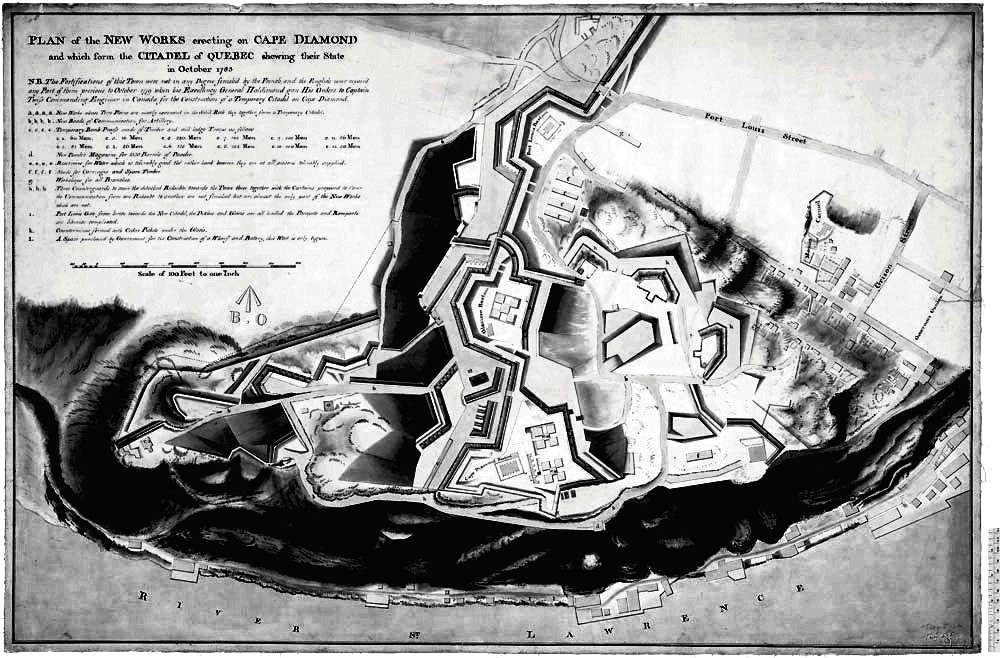

Vauban received and evaluated considerable information concerning the colonies of France including Canada, from some of the administrators and officers that he knew there, and from engineers that were sent there following his recommendation.[246] Vauban also examined all plans of fortifications for New France, corrected them and sometimes executed changes to the drawings sent to him for review.[247] His correspondence with people in New France covered a great variety of subjects ranging from fortification to recommendations for town planning. For example, the work on the redoubt at Cape Diamond, Quebec, was carried out by Gedeon de Catalogne, under the direction of Marshal Vauban.[248] This fortification held dozens of guns and was built with solid earthworks faced with stone, which girdled the city from the Cape to St. Charles. Quebec as a fortress was considered impregnable, partly because it had been modeled on Vauban’s pattern of fortifications.[249]

Cape Diamond, Quebec, plan view of the fortifications, 1783. (Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4128628)

(Caporal David Robert, Musée Royal 22e Régiment Photo)

Aerial view of la Citadelle de Québec, 9 Sep 2011.

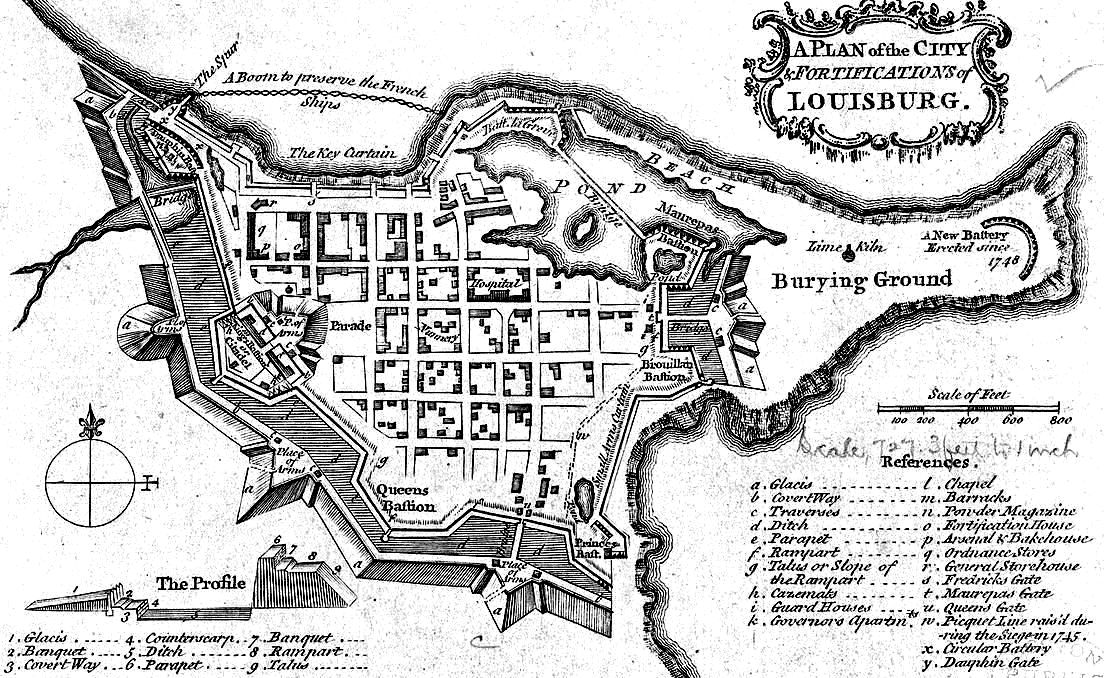

The star-shaped stronghold of Louisbourg sited in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, is in many respects the final memorial to the Marquis de Vauban.[250] Two of Vauban’s pupils, Verville and Verrier, made extensive use of Vauban’s ideas and designs to make the fortress of Louisbourg one of the greatest strongholds of New France.

Louisbourg, plan view of the fortifications, 1758.

The fortress of Louisbourg is built on a narrow headland, with water on three sides. The sea itself provides a moat, and on nine days out of ten the surf pounds hard on the rock-strewn shore. There is a string of shoals and islands that reduces the harbor entrance to a mere 400 yards, and which offers positions for gun emplacements that command the roadstead and the only channel into the harbor. The landward side was very marshy in its day, and would have severely impeded the movement of any heavy artillery that an enemy might try to drag onto the low hillocks that rise up over half a mile away. Built using Vauban’s principles, the walls were ten feet thick and faced with fitted masonry that rose thirty feet behind a steep ditch. This in turn was fronted by a wide glacis, with an unobstructed sloping field of fire that could be raked at point-blank range with cannon and musket shot. In places where the often-violent seashore itself was the first line of defence, additional earthworks and sometimes ponds and palisades were deemed to be sufficient. Enough gun emplacements for 148 cannon, including 24 and 42-pounder’s, jutted from the walls, enabling all-round fire, or massive concentrations at danger points. Covered ways gave shelter to the defenders against bomb splinters.[251]

In the end, following two sieges, Louisbourg was considered such a threat by the English that it had to be destroyed.[252] The characteristic outlines of the plan of this fortress, which was strongly influenced by the concepts of Vauban, have become more discernible during the continuing restoration of this remarkable fortress in present day Nova Scotia. The sieges that overcame it are discussed in the following chapter.

Louisbourg, 1745

Serendipity sometimes has a role to play in the successful outcome of a siege. During the first siege of Louisbourg on 28 May 1745, the combined forces of William Pepperell and Admiral Warren lacked the heavy cannon needed to reduce the fortifications of the Gabarus island battery blocking access to the harbor defenses. This was due to poor and hasty planning, and should have caused the siege to end in failure. During a reconnaissance by a landing party however, a sharp eyed man looking down into the clear water saw what incredibly appeared to be a whole battery of guns half hidden in the sand below. This is exactly what it was, ten bronze cannon which had slid from the deck of a French Man-o’-War years earlier and had been left in the water by the profligate Governor. The men swiftly raised the guns, scoured them off, hoisted them onto the headland and were soon blasting shot across the half-mile gap onto the French battery. When one shot finally hit the island’s powder magazine, the French commander d’Aillebout had to surrender. With this vital position in hand the siege was then brought to a successful conclusion, having lasted 46 days.

(F. Stephen)

English landing on Cape Breton Island to attack the fortress of Louisbourg in 1745.

After Louisbourg’s surrender and occupation, Admiral Warren put the French flag back up. Thus, French ships kept sailing into Louisbourg’s harbour, including one carrying a cargo of gold and silver bars. 850 guinea’s was given to every sailor as prize money.[253]

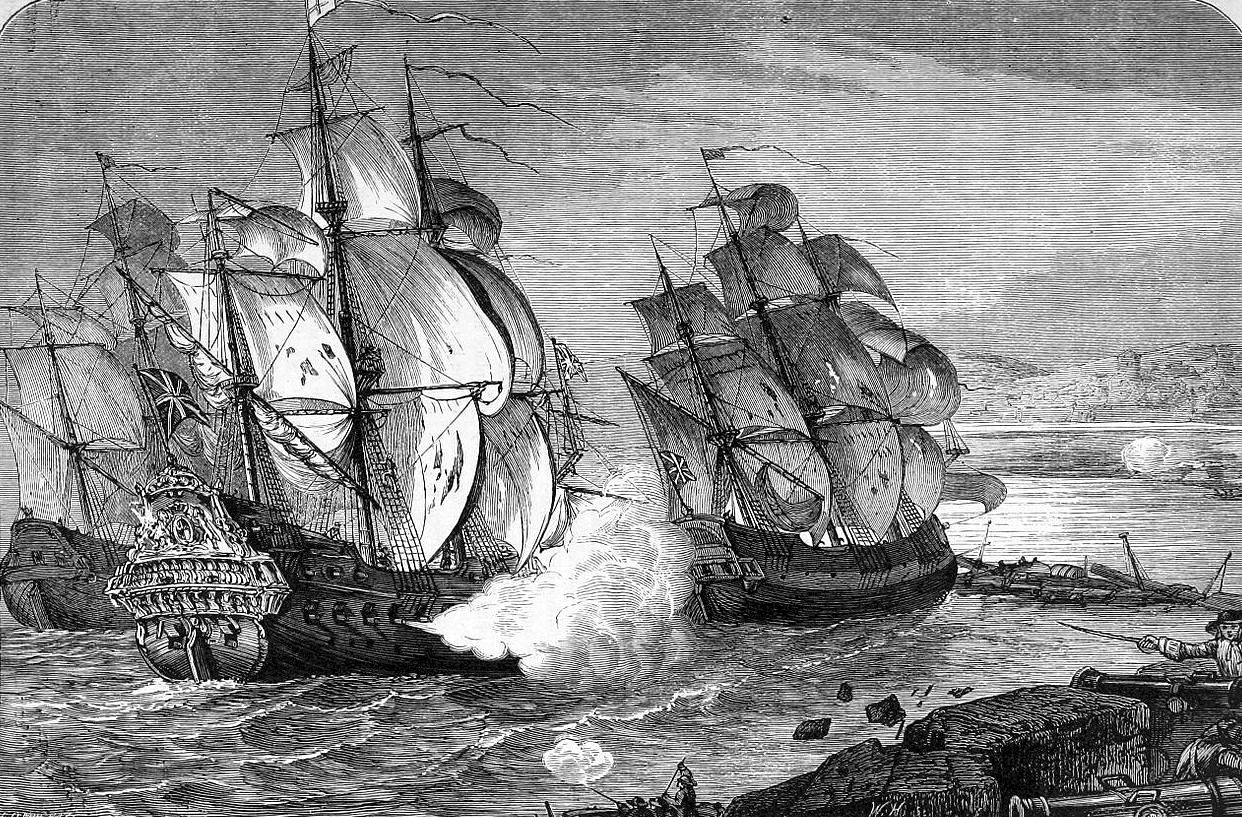

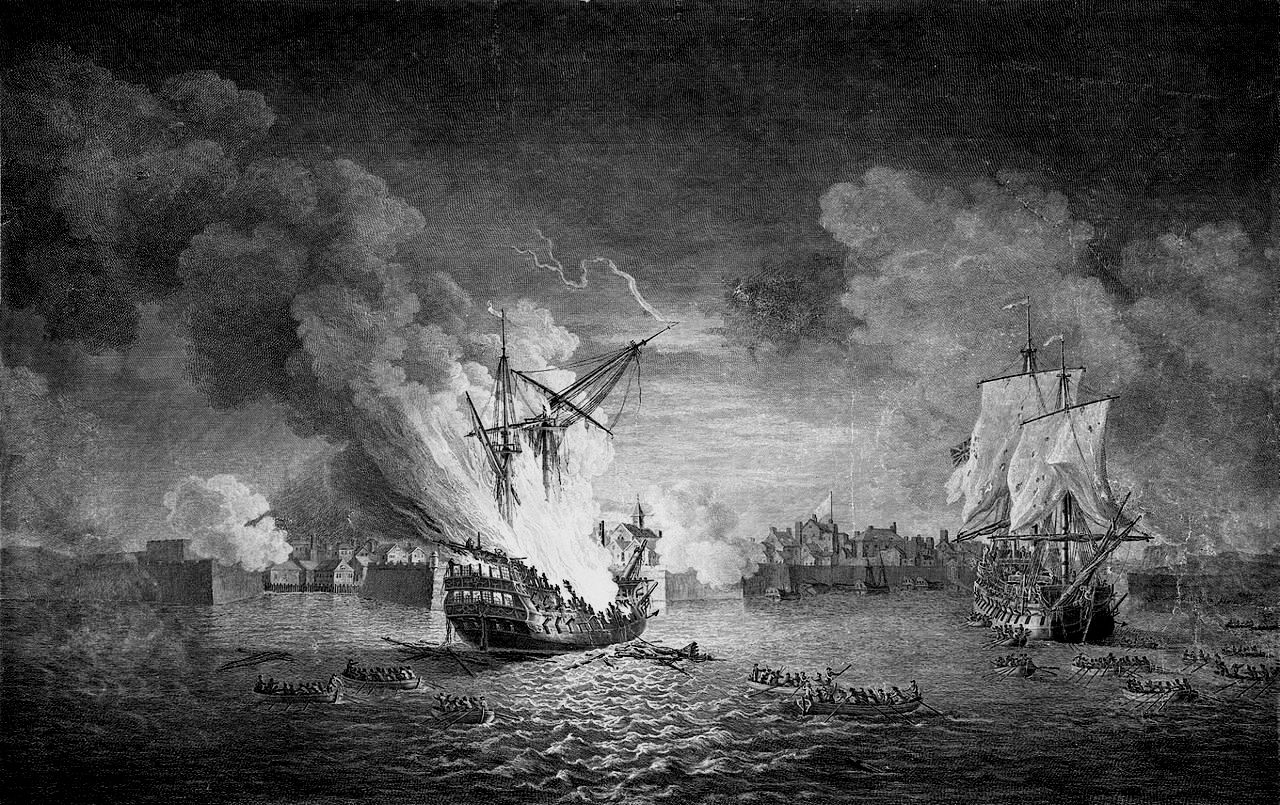

Engraving made after a painting by Richard Paton. Burning of the French ship Prudent 74 guns and capture of Bienfaisant 64 guns during the siege of Louisbourg in 1758.

(Thomas Nelson)

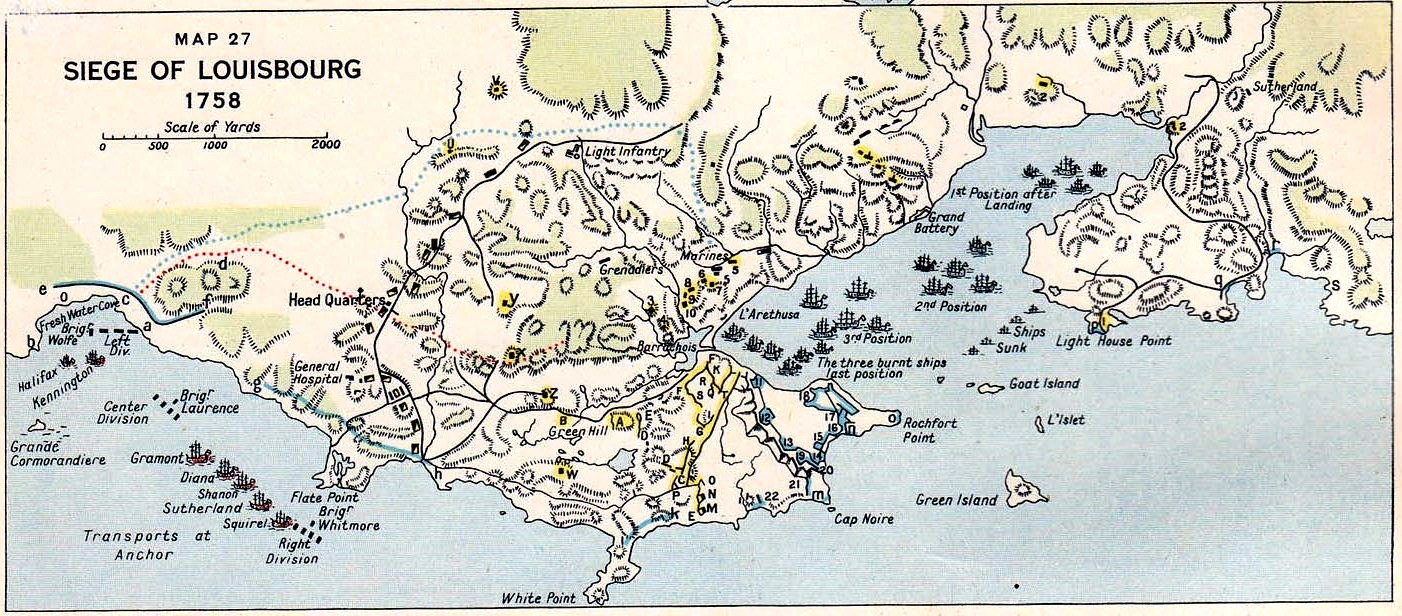

Map of the siege of Louisbourg, 1958.

Siege of Louisbourg, 1758

The second siege of Louisbourg was more orthodox in example, and was fought 1-26 July 1758. The French forces of Governor Augustin de Droucourt defended the fortress with 3,080 men and 219 cannon against the combined forces of Major General Amherst and Admiral Boscawen. With 25,000 men and 1,842 guns afloat, some 200 ships left England in February 1758 with orders to take Canada. James Wolfe was one of the three brigade commanders onboard. The force conducted amphibious training in Halifax before sailing to Louisbourg where a 49-day siege was successfully carried out. The fortress was bombarded in a well-planned and concerted manner, to the point where the defenders were left with only three cannon able to fire, at which point Governor Augustin surrendered. Shortly afterwards, the task force set off to take Quebec, which fell to Wolfe on 13 September 1759.[254]

Surrender of Louisbourg, 1758.

Siege of Yorktown, 1781

The Siege of Yorktown began on 29 Sep and ended on 19 Oct 1781 aat Yorktown, Virginia. It was a decisive victory by a combined force of American Continental Army troops led by General George Washington and French Army troops led by the Comte de Rochambeau over a British Army commanded by British peer and Lieutenant-General Charles Cornwallis. As the culmination of the Yorktown campaign, the siege proved to be the last major land battle of the American Revolutionary War in the North American theatre, as the surrender by Cornwallis, and the capture of both him and his army, prompted the British government to negotiate an end to the conflict. The battle boosted faltering American morale and revived French enthusiasm for the war, as well as undermining popular support for the conflict in Great Britain.

In 1780, approximately 5,500 French soldiers landed in Rhode Island to assist their American allies in operations against British-controlled New York City. Following the arrival of dispatches from France that included the possibility of support from the French West Indies fleet of the Comte de Grasse, Washington and Rochambeau decided to ask de Grasse for assistance either in besieging New York, or in military operations against a British army operating in Virginia. On the advice of Rochambeau, de Grasse informed them of his intent to sail to the Chesapeake Bay, where Cornwallis had taken command of the army. Cornwallis, at first given confusing orders by his superior officer, Henry Clinto, was eventually ordered to build a defensible deep-water port, which he began to do in Yorktown, Virginia. Cornwallis’ movements in Virginia were shadowed by a Continental Army force led by the Marquis de Lafayette.

The French and American armies united north of New York City during the summer of 1781. When word of de Grasse’s decision arrived, both armies began moving south toward Virginia, engaging in tactics of deception to lead the British to believe a siege of New York was planned. De Grasse sailed from the West Indies and arrived at the Chesapeake Bay at the end of August, bringing additional troops and creating a naval blockade of Yorktown. He was transporting 500,000 silver pesos collected from the citizens of Havana, Cuba, to fund supplies for the siege and payroll for the Continental Army. While in Santo Domingo, de Grasse met with Francisco Saavedra Sangronis, an agent of Carlos III of Spain. De Grasse had planned to leave several of his warships in Santo Domingo. Saavedra promised the assistance of the Spanish navy to protect the French merchant fleet, enabling de Grasse to sail north with all of his warships. In the beginning of September, he defeated a British fleet led by Sir Thomas Graves that came to relieve Cornwallis at the Battle of the Chesapeake. As a result of this victory, de Grasse blocked any escape by sea for Cornwallis. By late September Washington and Rochambeau arrived, and the army and naval forces completely surrounded Cornwallis.

After initial preparations, the Americans and French built their first parallel and began the bombardment. With the British defense weakened, on 14 Oct1781 Washington sent two columns to attack the last major remaining British outer defenses. A French column under Wilhelm of the Palatinate-Zweibrücken took Redoubt No. 9 and an American column under Alexander Hamilton took Redoubt No. 10. With these defenses taken, the allies were able to finish their second parallel. With the American artillery closer and its bombardment more intense than ever, the British position began to deteriorate rapidly and Cornwallis asked for capitulation terms on 17 Oct. After two days of negotiation, the surrender ceremony occurred on 19 Oct; Lord Cornwallis was absent from the ceremony. With the capture of more than 7,000 British soldiers, negotiations between the United States and Great Britain began, resulting in the Treaty of Paris of 1783. (Alden, John. A History of the American Revolution. New York: Da Capo Press, 1969)

Yorktown, surrender of British forces, 1781. This painting by John Trumbull depicts the forces of British Major General Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis (1738-1805) (who was not himself present at the surrender), surrendering to French and American forces after the Siege of Yorktown (September 28 – October 19, 1781) during the American Revolutionary War. The central figures depicted are Generals Charles O’Hara and Benjamin Lincoln.

Siege of Gibraltar, 1782

Gibraltar is a British Overseas Territory located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula. It has an area of 6.7 km2 (2.6 sq mi) and is bordered to the north by Spain. The landscape is dominated by the Rock of Gibraltar at the foot of which is a densely populated city area, home to over 30,000 people.

In 1704, Anglo-Dutch forces captured Gibraltar from Spain during the War of the Spanish Succession on behalf of the Habsburg claim to the Spanish throne. The territory was ceded to Great Britain in perpetuity under the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. During the Second World War it was an important base for the Royal Navy as it controlled the entrance and exit to the Mediterranean Sea, which is only 8 miles (13 km) wide at this naval “choke pont”. It remains strategically important to this day, with half the world’s seaborne trade passing through the strait

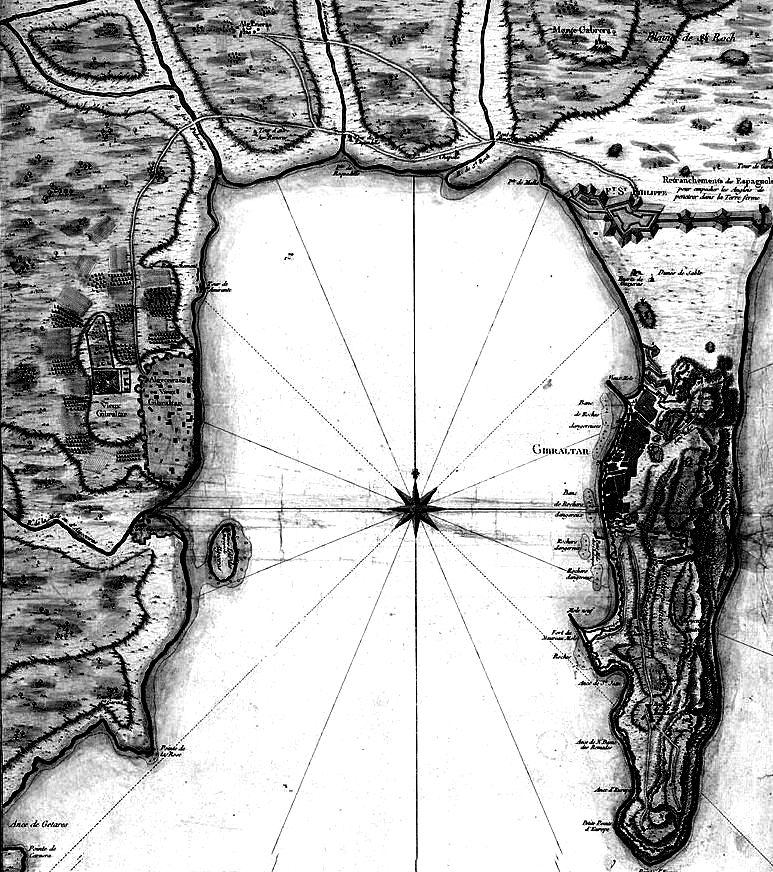

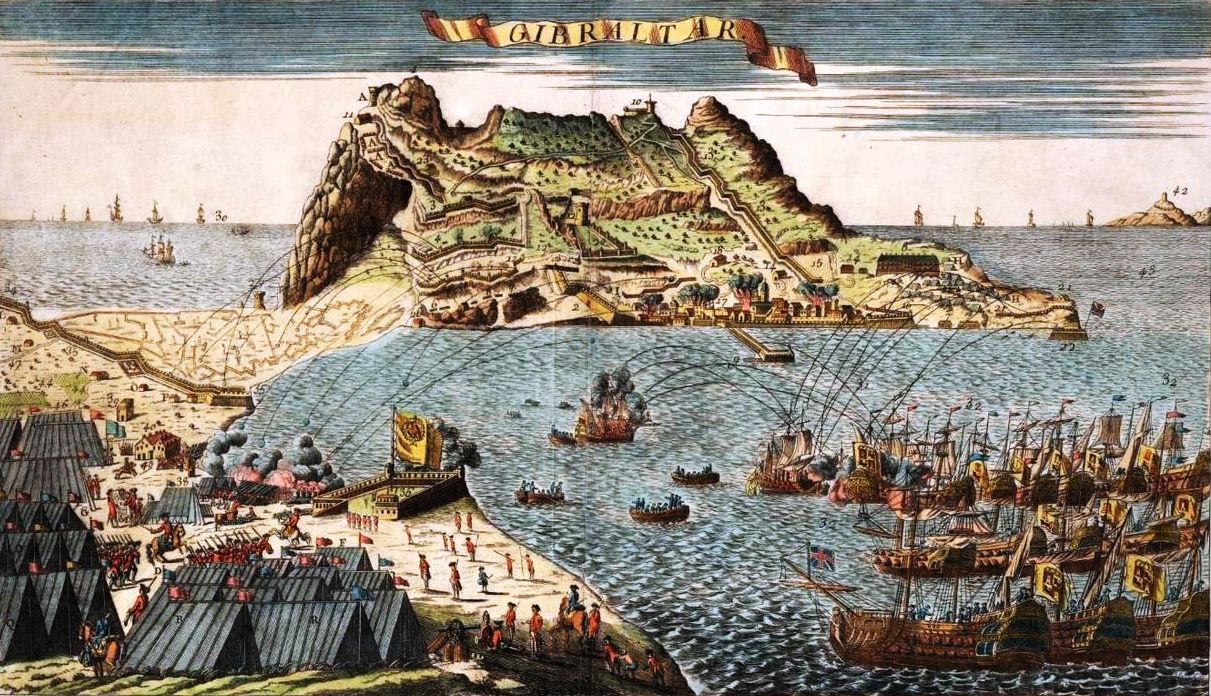

The siege of Gibraltar by the Spanish in July 1782, demonstrated that old artillery tactics from the 15th century could be successfully adapted to more modern times. The British garrison on Gibraltar had successfully held out for three full years, when the Spanish tried a new siege method. They built ten ships armored six feet thick with green timbers reinforced by iron, cork and raw hides. Mounting heavy siege artillery on these gunboats, they anchored near the British works and began a harsh pounding of Gibraltar’s defenses. Ordinary round shot buried themselves harmlessly in the wooden armor, but the garrison had been experimenting with cannon balls heated in furnaces. The shore guns changed to red-hot shot, and after 8,300 rounds the grand assault failed with every Spanish ship blown up or burnt down to the water line. Although the siege lasted seven more months, “the Rock” was never again in serious danger.[255]

Gibraltar and Bay map, 1750.

Panoramic view of Gibraltar under siege from Spanish fleet and land positions in foreground, created in 1778.

(Steve Photo)

An aerial photo of Gibraltar after take-off from the Rock, looking north-west towards San Roque, 23 Aug 2011.

Siege of the Alamo, 1836

The Battle of the Alamo (23 Feb – 6 March 1836) was a pivotal event in the Texas Revolution. Following a 13-day siege, Mexican troops under President General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna launched an assault on the Alamo Mission near San Antonio de Béxar (modern-day San Antonio, Texas), killing all of the Texian defenders. Santa Anna’s cruelty during the battle inspired many Texians, both Texas settlers and adventurers from the United States, to join the Texian Army. Buoyed by a desire for revenge, the Texians defeated the Mexican Army at the Battle of San Jacinto, on 21 April 1836, ending the revolution.

The siege of the Alamo took place during what is known as the Texan War of Independence. Texas had been a state of Mexico until American settlers north of the Rio Grande began agitating for independence. After losing San Antonio to the Texans during the Siege of the Bexar, Mexican General Antonio de Santa Anna was determined to retake this key location and at the same time impress upon the Texans the futility of further resistance to Mexican rule. With these goals in mind, Santa Anna marched into Texas with some 6,000 troops under his command. The vanguard of his army arrived in San Antonio about 23 February 1836. Some 145 Texans in the area took refuge in the fortified grounds of an old Spanish Franciscan mission that had been converted into a fort. It was known as Alamo, and at the time of the siege was under the joint command of the Commandant, William B. Travis (for the regular army), and James Bowie (for the volunteers). Famous American frontiersmen Davy Crockett and James Bonham were also participants in the battle.

Over the following two weeks, the Mexican forces continually strengthened to over 2000 troops. During the same period, a few reinforcements for the Texans answered Travis’ famous appeal for aid and managed to penetrate enemy lines and enter the Alamo grounds, bringing the total strength of the defenders to about 189 men.

After periodic bombardment, the siege ended on the morning of 6 March 1836, when the Mexicans stormed the Alamo fortress. During the battle, no quarter was given, and all of the Texan defenders were killed. Several non-combatants were spared, including Susanna Dickenson, the wife of one of the defenders, Susanna’s baby, and a servant of Travis. Partly to reinforce his goal of terrorizing colonists in Texas, Santa Anna released this small party to inform Texans of the fate of the defenders.

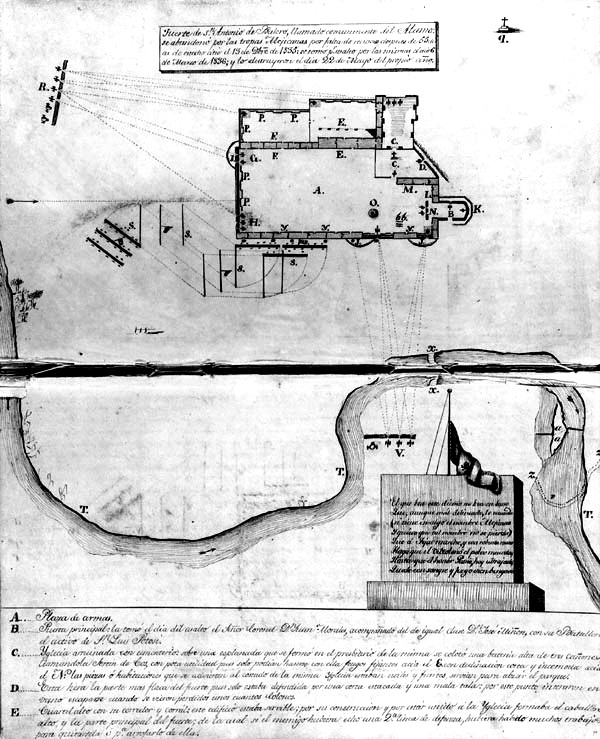

Plan of the Alamo, by José Juan Sánchez-Navarro, 1836. This manuscript map, part of an official military report on the fall of the Alamo, clearly shows where the Mexicans had positioned their cannons (at R and V) and the line of attack of troops under General Cos (S). (he Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin; CN 01579a)

(Robert Jenkins Onderdonk)

The Fall of the Alamo, Davy Crockett is wielding his rifle as a club against Mexican troops who have breached the walls of the mission.

Losses in the battle have been placed at 189 Texans against about 1,600 for the Mexicans. This was only the first of eight battles that Santa Anna would fight against American troops. He continued his march eastward, destroying American settlements that lay in his path, until he reached Galveston Bay five weeks later. In a convention at Washington on 2 March 1866, Texas had proclaimed its independence from Mexico. Sam Houston was named commander of the Army. On 21 April, Houston met Santa Anna’s 1,200 Mexicans along the western bank of the San Jacinto River near its mouth. In spite of being outnumbered, the Texans routed the Mexicans, and captured Santa Anna. He agreed to recognize the independence of Texas (although this agreement was later repudiated by the Mexican Congress). Texas would later be admitted to the United States on 29 December 1845.[256]

(Author Photo)

The Alamo as it appears today.

Siege of Lucknow, 1857

The Siege of Lucknow was the prolonged defence of the British Residency (a group of several buildings in a common precinct in the city of Lucknow). It served as the residence for the British Resident General who was a representative in the court of the Nawab. Construction took place between 1780 and 1800 AD. Between 1 July 1857 and 17 November 1857 the Residency was subject to the siege during the Indian Rebellion of 1857. After two successive relief attempts had reached the city, the defenders and civilians were evacuated from the Residency, which was then abandoned.

Engraving of The Residency in Lucknow, 1857.

The state of Oudh/Awadh had been annexed by the British East India Company and the Nawab Wajid Ali Shah was exiled to Calcutta the year before the rebellion broke out. This high-handed action by the East India Company was greatly resented within the state and elsewhere in India. The first British Commissioner (in effect the governor) appointed to the newly acquired territory was Coverley Jackson. He behaved tactlessly, and Sir Henry Lawrence, a very experienced administrator, took up the appointment only six weeks before the rebellion broke out.

The sepoys (Indian soldiers) of the East India Company’s Bengal Presidency Army had become increasingly troubled over the preceding years, feeling that their religion and customs were under threat from the evangelising activities of the Company. Lawrence was well aware of the rebellious mood of the Indian troops under his command (which included several units of Oudh Irregulars, recruited from the former army of the state of Oudh). On 18 April, he warned the Governor General, Lord Canning, of some of the manifestations of discontent, and asked permission to transfer certain rebellious corps to another province.

The flashpoint of the rebellion was the introduction of the Enfield rifle; the cartridges for this weapon were believed to be greased with a mixture of beef and pork fat, which was felt would defile both Hindu and Muslim Indian soldiers. On 1 May, the 7th Oudh Irregular Infantry refused to bite the cartridge, and on 3 May they were disarmed by other regiments.

On 10 May, the Indian soldiers at Meerut broke into open rebellion, and marched on Delhi. When news of this reached Lucknow, Lawrence recognised the gravity of the crisis and summoned from their homes two sets of pensioners, one of sepoys and one of artillerymen, to whose loyalty, and to that of the Sikh and some Hindu sepoys, the successful defence of the Residency was largely due.

On 23 May, Lawrence began fortifying the Residency and laying in supplies for a siege; large numbers of British civilians made their way there from outlying districts. On 30 May (the Muslim festival of Eid ul-Fitr), most of the Oudh and Bengal troops at Lucknow broke into open rebellion. In addition to his locally recruited pensioners, Lawrence also had the bulk of the British 32nd Regiment of Foot available, and they were able to drive the rebels away from the city.

On 4 June, there was a rebellion at Sitapur, a large and important station 51 miles (82 km) from Lucknow. This was followed by another at Faizabad, one of the most important cities in the province, and outbreaks at Daryabad, Sultanpur and Salon. Thus, in the course of ten days, British authority in Oudh practically vanished.

On 30 June, Lawrence learned that the rebels were gathering north of Lucknow and ordered a reconnaissance in force, despite the available intelligence being of poor quality. Although he had comparatively little military experience, Lawrence led the expedition himself. The expedition was not very well organised. The troops were forced to march without food or adequate water during the hottest part of the day at the height of summer, and at the Chinhat they met a well-organised rebel force, led by Barkat Ahmad with cavalry and dug-in artillery . Whilst they were under attack, some of Lawrence’s sepoys and Indian artillerymen defected to the rebels, overturning their guns and cutting the traes. His exhausted British soldiers retreated in disorder. Some died of heatstroke within sight of the Residency.

Lieutenant William George Cubitt, 13th Native Infantry, was awarded the Victoria Cross several years later, for his act of saving the lives of three men of the 32nd Regiment of Foot during the retreat. His was not a unique action; sepoys loyal to the British, especially those of the 13th Native Infantry, saved many British soldiers, even at the cost of abandoning their own wounded men, who were hacked to pieces by rebel sepoys.

As a result of the defeat, the detached turreted building, Machchhi Bhawan (Muchee Bowan), which contained 200 barrels (~27 t) of gunpowder and a large supply of ball cartridges, was blown up and the detachment withdrew to the Residency.

Lawrence retreated into the Residency, where the siege now began, with the Residency as the centre of the defences. The actual defended line was based on six detached smaller buildings and four entrenched batteries. The position covered some 60 acres (240,000 m2) of ground, and the garrison (855 British officers and soldiers, 712 Indians, 153 civilian volunteers, with 1,280 non-combatants, including hundreds of women and children) was too small to defend it effectively against a properly prepared and supported attack. Also, the Residency lay in the midst of several palaces, mosques and administrative buildings, as Lucknow had been the royal capital of Oudh for many years. Lawrence initially refused permission for these to be demolished, urging his engineers to “spare the holy places”. During the siege, they provided good vantage points and cover for rebel sharpshooters and artillery.

One of the first bombardments following the beginning of the siege, on 30 June, caused a civilian to be trapped by a falling roof. Corporal William Oxenham of the 32nd Foot saved him while under intense musket and cannon fire, and was later awarded the Victoria Cross. The first attack was repulsed on 1 July. The next day, Lawrence was fatally wounded by a shell, dying on 4 July. Colonel John Inglis of the 32nd Regiment took military command of the garrison. Major John Banks was appointed the acting Civil Commissioner by Lawrence. When Banks was killed by a sniper a short time later, Inglis assumed overall command.

About 8,000 sepoys who had joined the rebellion and several hundred retainers of local landowners surrounded the Residency. They had some modern guns and also some older pieces which fired all sorts of improvised missiles. There were several determined attempts to storm the defences during the first weeks of the siege, but the rebels lacked a unified command able to coordinate all the besieging forces.

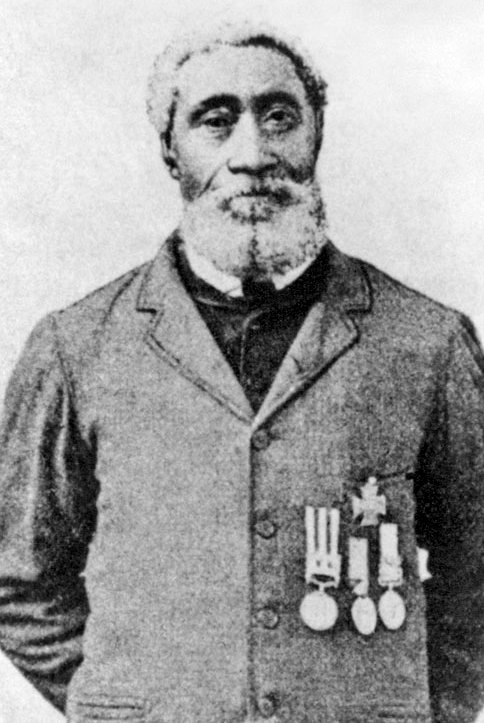

The defenders, their number constantly reduced by military action as well as disease, were able to repulse all attempts to overwhelm them. On 5 August an enemy mine was foiled; counter mining and offensive mining against two buildings brought successful results. Several sorties were mounted, attempting to reduce the effectiveness of the most dangerous rebel positions and to silence some of their guns. The Victoria Cross was awarded to several participants in these sorties: Captain Samuel Hill Lawrence and Private William Dowling of the 32nd Foot and Captain Robert Hope Moncrieff Aitken of the 13th Native Infantry. Also William Hall (Quartermaster) was awarded a Victoria Cross, because he bravely stayed his ground and shot the wall (under heavy cannon and musket fire) down when only him and a officer were still alive.

Captain of the Foretop, Quartermaster William Hall, VC.

“On the west of Lucknow stood a huge mosque, the Shah Najaf, from which issued a deadly hail of musket balls and grenades. The British had to take the mosque, but without scaling ladders and with a 6-metre wall to surmount, they had to breech the walls. They dragged the guns to within 350 metres of the wall, banging shell after shell at it, making little impact. The guns had to move closer.”

“The sailors dragged the guns up, sustaining heavy casualties in the process. The mosque walls were loopholed in such a way that the naval gunners were safe from fire at a certain point. But every shot from the big guns caused them to recoil back into the fire zone. Soon only Hall and one officer, Lt Thomas Young, who was wounded, were still standing to man their 24-pounder gun. Hall, now Number One on the gun, kept loading and firing, dragging it back after every recoil, over and over. Finally the wall was breached sufficiently to allow a number of Highlanders to scramble through and open the gate to admit the rest of the force. For his heroic actions that 16 November 1857, Hall was awarded the Victoria Cross. He served in the Royal Navy until 1876, then retired in Horton Bluff, Nova Scotia, where he lived until his death.”

The joint citation in the Gazette reads:

Lieutenant (now Commander) Young, late Gunnery Officer of Her Majesty’s ship ” Shannon,” and William Hall, “Captain of the Foretop,” of that Vessel, were recommended by the late Captain Peel for the Victoria Cross, for their gallant conduct at a 24-Pounder Gun, brought up to the angle of the Shah Nujjiff, at Lucknow, on 16 November 1857.

(In February 2010 Canada Post issued a commemorative stamp honouring Hall’s VC. On 26 June 2015 it was announced that the fourth ship in the Royal Canadian Navy’s Harry DeWolf class would be named for William Hall. The ship will be constructed at the Halifax Shipyards in Halifax.)

On 16 July, a force under Major General Henry Havelock recaptured Cawnpore, 48 miles (77 km) from Lucknow. On 20 July, he decided to attempt to relieve Lucknow, but it took six days to ferry his force of 1500 men across the Ganges River. On 29 July, Havelock won a battle at Unao, but casualties, disease and heatstroke reduced his force to 850 effectives, and he fell back.

Havelock managed to get a spy through to the Residency, telling them that 2 rockets would be fired at a certain time on the night when the relief force was ready to attack. There followed a sharp exchange of letters between Havelock and the insolent Brigadier James Neill who was left in charge at Cawnpore. Havelock eventually received 257 reinforcements and some more guns, and tried again to advance. He won another victory near Unao on 4 August, but was once again too weak to continue the advance, and retired.

Havelock intended to remain on the north bank of the Ganges, inside Oudh, and thereby prevent the large force of rebels which had been facing him from joining the siege of the Residency, but on 11 August, Neill reported that Cawnpore was threatened . To allow himself to retreat without being attacked from behind, Havelock marched again to Unao and won a third victory there. He then fell back across the Ganges, and destroyed the newly completed bridge. On 16 August, he defeated a rebel force at Bithur, disposing of the threat to Cawnpore.

Havelock’s retreat was tactically necessary, but caused the rebellion in Oudh to become a national revolt, as previously uncommitted landowners joined the rebels.

Havelock had been superseded in command by Major General Sir James Outram. Before Outram arrived at Cawnpore, Havelock made preparations for another relief attempt. He had earlier sent a letter to Inglis in the Residency, suggesting he cut his way out and make for Cawnpore. Inglis replied that he had too few effective troops and too many sick, wounded and non-combatants to make such an attempt. He also pleaded for urgent assistance. The rebels meanwhile continued to shell the garrison in the Residency, and also dug mines beneath the defences, which destroyed several posts. Although the garrison kept the rebels at a distance with sorties and counter-attacks, they were becoming weaker and food was running short.

Outram arrived at Cawnpore with reinforcements on 15 September. He allowed Havelock to command the relief force, accompanying it nominally as a volunteer until Lucknow was reached. The force numbered 3,179 and was composed of six British and one Sikh infantry battalions, with three artillery batteries, but only 168 volunteer cavalry. They were divided into two brigades, under Neill and Colonel Hamilton of the 78th Highlanders.

The advance resumed on 18 September. This time, the rebels did not make any serious stand in the open country, even failing to destroy some vital bridges. On 23 September, Havelock’s force drove the rebels from the Alambagh, a walled park four miles south of the Residency. Leaving the baggage with a small force in the Alambagh, he began the final advance on 25 September. Because of the monsoon rains, much of the open ground around the city was flooded or waterlogged, preventing the British making any outflanking moves and forcing them to make a direct advance through part of the city.

The force met heavy resistance trying to cross the Charbagh Canal, but succeeded after nine out of ten men of a Forlorn Hope were killed storming a bridge. They then turned to their right, following the west bank of the canal. The 78th Highlanders took a wrong turning, but were able to capture a rebel battery near the Qaisarbagh palace, before finding their way back to the main force. After further heavy fighting, by nightfall the force had reached the Machchhi Bhawan. Outram proposed to halt and contact the defenders of the Residency by tunnelling and mining through the intervening buildings, but Havelock insisted on an immediate advance. (He feared that the defenders of the Residency were so weakened that they might still be overwhelmed by a last-minute rebel attack.) The advance was made through heavily defended narrow lanes. Neill was one of those killed by rebel musket fire. In all, the relief force lost 535 men out of 2000, incurred mainly in this last rush.

By the time of the relief, the defenders of the Residency had endured a siege of 87 days, and were reduced to 982 fighting personnel. Originally, Outram had intended to evacuate the Residency, but the heavy casualties incurred during the final advance made it impossible to remove all the sick and wounded and non-combatants. Another factor which influenced Outram’s decision to remain in Lucknow was the discovery of a large stock of supplies beneath the Residency, sufficient to maintain the garrison for two months. Lawrence had laid in the stores, but died before he had informed any of his subordinates. (Inglis had feared that starvation was imminent.)

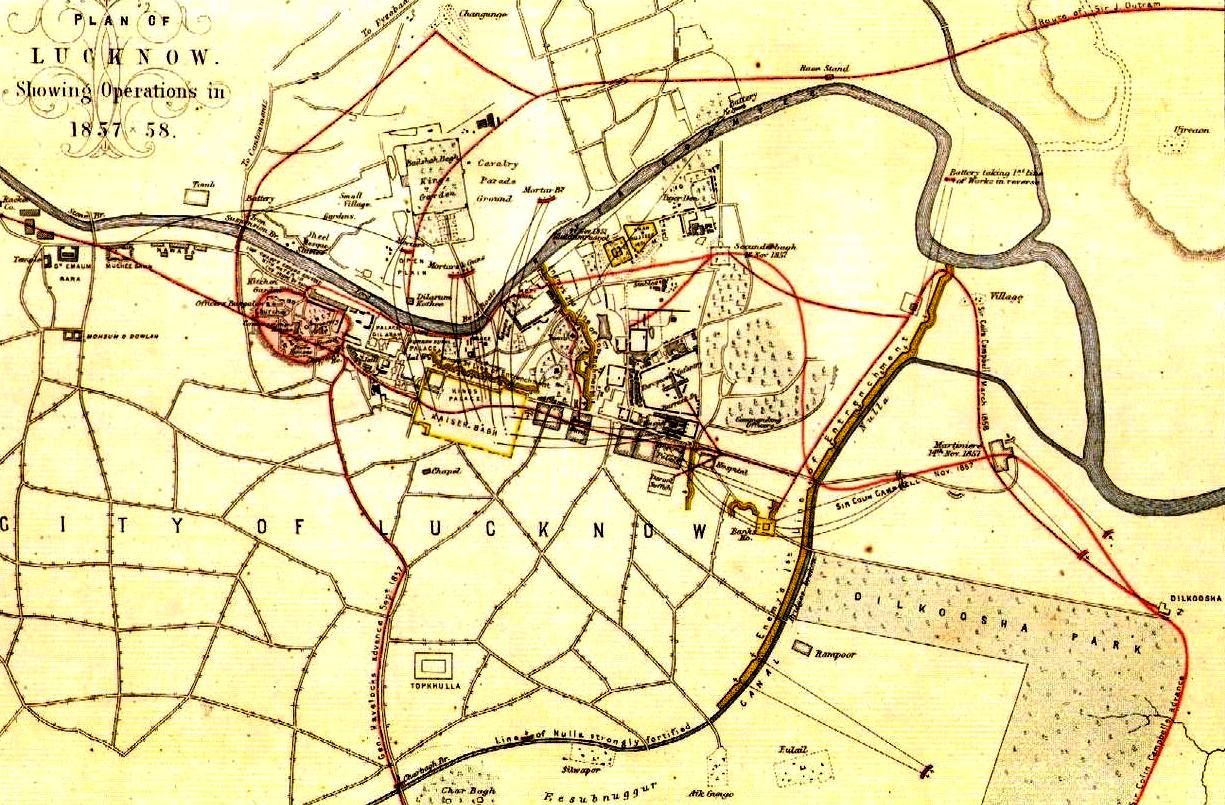

Map of the entrenched positions of the British garrison at Lucknow in 1857.

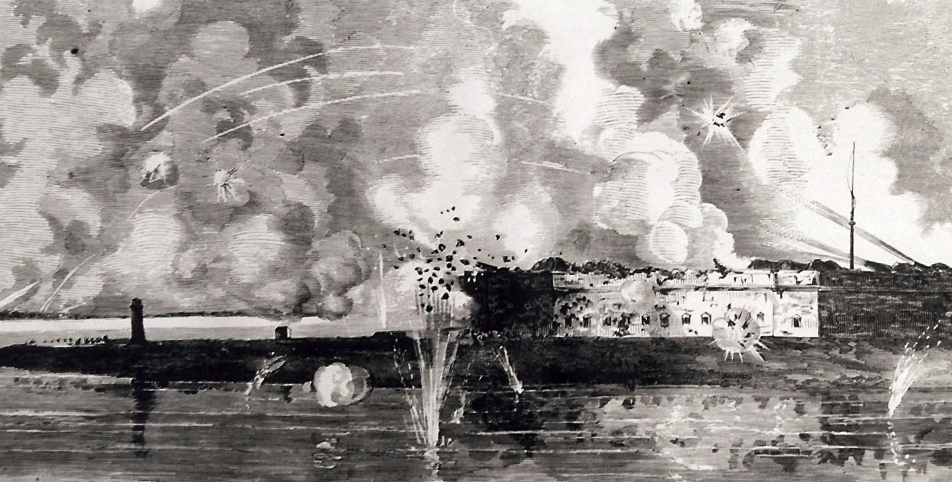

Instead, the defended area was enlarged. Under Outram’s overall command, Inglis took charge of the original Residency area, and Havelock occupied and defended the palaces (the Farhat Baksh and Chuttur Munzil) and other buildings east of it. Outram had hoped that the relief would also demoralise the rebels, but was disappointed. For the next six weeks, the rebels continued to subject the defenders to musket and artillery fire, and dug a series of mines beneath them. The defenders replied with sorties, as before, and dug counter-mines. Twenty-one shafts were sunk and 3,291 feet of gallery were constructed by the defenders. The enemy dug 20 mines: three caused loss of life, two did no injury, seven were blown in, and seven were tunnelled into and their galleries taken over.