Introduction to the story of Sieges

(19th Century Print)

French capture of Saigon, 17 Feb 1859.

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or by a well-prepared assault. This derives from sedere, latin for “to sit”. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characterized by one party holding a strong, static, defensive position. Consequently, an opportunity for negotiation between combatants is not uncommon, as proximity and fluctuating advantage can encourage diplomacy.

A siege occurs when an attacker encounters a city or fortress that cannot be easily taken by a quick assault, and which refuses to surrender. Sieges involve surrounding the target to block the provision of supplies and the reinforcement or escape of troops (a tactic known as “investment”). This is typically coupled with attempts to reduce the fortifications by means of siege engines, artillery bombardment, mining (also known as sapping), or the use of deception or treachery to bypass defenses.

Failing a military outcome, sieges can often be decided by starvation, thirst, or disease, which can afflict either the attacker or defender. This form of siege can take many months or even years, depending upon the size of the stores of food the fortified position holds.

The attacking force can circumvallate the besieged place, which is to build a line of earth-works, consisting of a rampart and trench, surrounding it. During the process of circumvallation, the attacking force can be set upon by another force, an ally of the besieged place, due to the lengthy amount of time required to force it to capitulate. A defensive ring of forts outside the ring of circumvallated forts, called contravallation, is also sometimes used to defend the attackers from outside.

Ancient cities in the Middle East show archaeological evidence of having had fortified city walls. During the Wrring States era of ancient China, there is both textual and archaeological evidence of prolonged sieges and siege machinery used against the defenders of city walls. Siege machinery was also a tradition of the ancient Greco-Roman world. During the Renaissance and the early modern period, siege warfare dominated the conduct of war in Europe. Leonardo da Vince gained as much of his renown from the design of fortifications as from his artwork.

Medieval campaigns were generally designed around a succession of sieges. In the Napoleonic era, increasing use of ever more powerful cannon reduced the value of fortifications. In the 20th century, the significance of the classical siege declined. With the advent of mobile warfare, a single fortified stronghold is no longer as decisive as it once was. While traditional sieges do still occur, they are not as common as they once were due to changes in modes of battle, principally the ease by which huge volumes of destructive power can be directed onto a static target. Modern sieges are more commonly the result of smaller hostage, militant, or extreme resisting arrest situations. (Duffy, Christopher. Siege Warfare: Fortress in the Early Modern World, 1494–1660. Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1996)

Before Fortresses

Since the beginning of time, man has sought to defend himself and his family by finding a shelter or building a strong fortification. In equal measure and determination there have been those who have sought to overcome these defenses, which generally consisted of three different methods of protective works. The earliest and most simple field fortifications often consisted of stakes, stones, ditches, abatis (an obstacle comprised of cut trees with their branches facing the enemy), and other common obstacles constructed just before a battle began and which were primarily only intended for temporary or immediate use during a battle. The techniques used often mirrored the basic techniques used by early hunters, who built obstacles whose design and implementation were derived from simple but effective pits and traps which had been used to catch animals. As attack methods grew in sophistication, more ingenious ideas and methods of defense came to be employed.

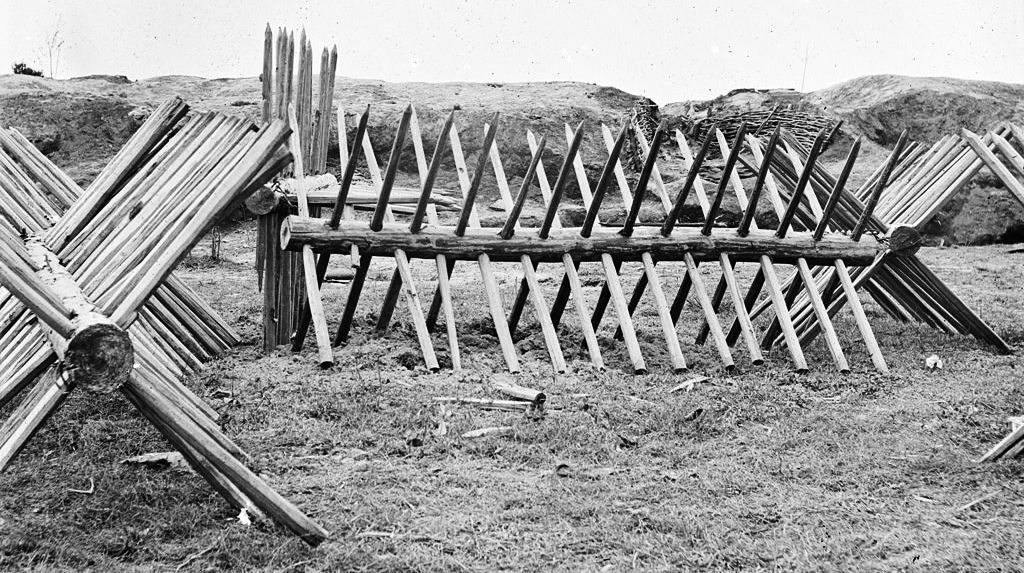

Sharpened stakes joined together to form a palisade came into increasing use, as well as traps set with a chevaux-de-frise (medieval defensive anti-cavalry measure consisting of a portable frame (sometimes just a simple log) covered with many projecting long iron or wooden spikes or spears). Improvements in the use of metallurgy contributed to the tools available to the defender, including such devices as the caltrop (shown above), a metal device which was formed from four iron spikes joined together in the form of a tetrahedron shape. Many of these devices would be thrown on the ground forward of a defensive position with the object of causing the attacker’s horse to stumble or fall, so unhorsing the rider or knight and rendering them more vulnerable in their cumbersome armor on the ground.

(Library of Congress Photo cwpb.02598)

Chevaux-de-frise used in the defence of the Confederate Fort Mahone at the Siege of Petersburg, Virginia, fought from 15 June 1864, to 2 April 1865, during the American Civil War. The campaign consisted of nine months of trench warfare in which Union forces commanded by Lieutenant-General Ulysses S. Grant assaulted Petersburg unsuccessfully and then constructed trench lines that eventually extended over 30 miles (48 km) from the eastern outskirts of Richmond, Virginia, to around the eastern and southern outskirts of Petersburg. Petersburg was crucial to the supply of Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s army and the Confederate capital of Richmond. Numerous raids were conducted and battles fought in attempts to cut off the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad. Many of these battles caused the lengthening of the trench lines. Lee finally gave in to the pressure and abandoned both cities in April 1865, leading to his retreat and surrender at the Appomattox Court House. The Siege of Petersburg foreshadowed the trench warfare that was common in the First World War, earning it a prominent position in military history.

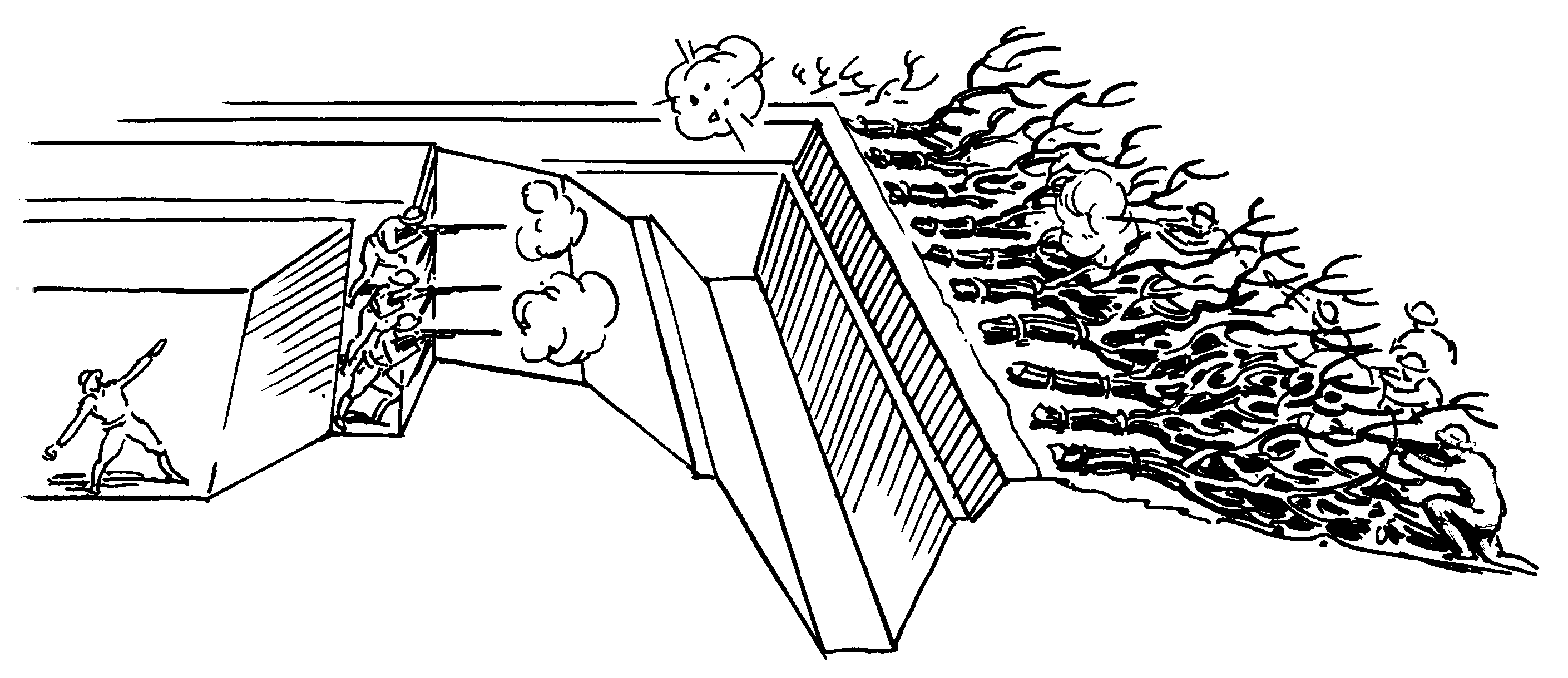

Abatis arrangment.

The use of stakes led in turn to the construction of more complex fortifications made of wood, as well as the idea of making them portable. William the Conqueror’s Norman troops, for example, brought pre-fabricated wooden castles with them when they landed in England in 1066, and the first thing they did on arrival was to erect one of them on the beach. The aim of these fortifications, and the reason they were initially effective, was to divide an attacker’s attention between trying to overcome them while simultaneously trying to keep his own forces protected.

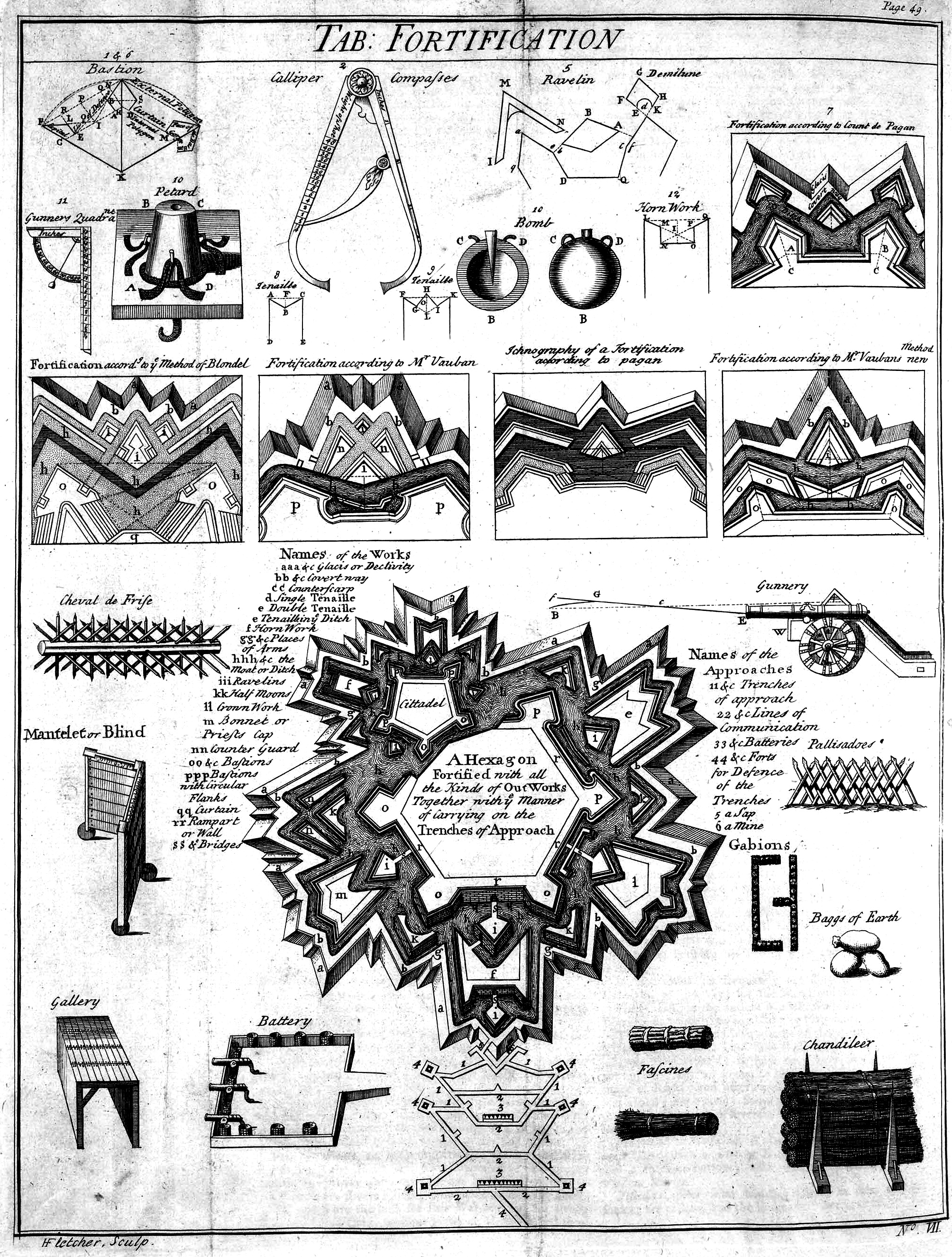

Table of fortification diagrams.

Fortifications, both temporary and long-term, have helped to decide the outcome in a number of very famous battles, including those at Crécy in 1346, Poitiers in 1356, and Agincourt in 1415.[3] In each of these specific battles, English archers fired their arrows from behind a protective shield of sharpened wooden stakes angled to face the assaulting French knights. Since the idea was effective, it remained little changed for centuries, and in fact variations on wooden stakes were used in Vietnamese defense works in the 1960s and 70s.

(Chapter CXXIX of Jean Froissart’s Chronicles, 15th century)

Battle of Crécy, 1346

The Battle of Crécy took place on 26 August 1346 in north-east France between a French army commanded by King Philip VI and an English army led by King Edward III. The French attacked the English while they were traversing northern France during the Hundred Years’ War resulting in an English victory and heavy loss of life among the French.

The English army had landed in the Cotentin Peninsula on 12 July. It had burnt a path of destruction through some of the richest lands in France to within 2 miles (3 km) of Paris, sacking many towns along the way. The English then marched north, hoping to link up with an allied Flemish army which had invaded from Flanders. Hearing that the Flemish had turned back, and having temporarily outdistanced the pursuing French, Edward had his army prepare a defensive position on a hillside near Crécy-en-Ponthieu. Late on 26 August the French army, which greatly outnumbered the English, attacked.

During a brief archery duel a large force of French mercenary crossbowmen was routed by Welsh and English longbowmen. The French then launched a series of cavalry charges by their mounted knights. These were disordered by their impromptu nature, by having to force their way through the fleeing crossbowmen, by the muddy ground, by having to charge uphill, and by the pits dug by the English. The attacks were further broken up by the effective fire from the English archers, which caused heavy casualties. By the time the French charges reached the English men-at-arms, who had dismounted for the battle, they had lost much of their impetus. The ensuing hand-to-hand combat was described as “murderous, without pity, cruel, and very horrible”. The French charges continued late into the night, all with the same result: fierce fighting followed by a French repulse.

Other accounts report that Genoese crossbowmen had led the assault, but they were soon overwhelmed by King Edward’s 10,000 longbowmen, who could reload faster and fire much further. The crossbowmen had then retreated and the French mounted knights attempted to penetrate the English infantry lines. In charge after charge, the horses and riders were cut down in the merciless shower of arrows. At nightfall, the French finally withdrew. Nearly a third of their army lay slain on the field, including King Philip VI’s brother, Charles II of Alencon (1297-1346); his allies King John of Bohemia (1296-1346) and Louis of Nevers (1304-46); and some 1,500 other knights and esquires. King Philip was wounded but survived. English losses were considerably lower.

The English then laid siege to the port of Calais. The battle crippled the French army’s ability to relieve the siege; the town fell to the English the following year and remained under English rule for more than two centuries, until 1558. Crécy established the effectiveness of the longbow as a dominant weapon on the Western European battlefield.

(King John at the Battle of Poitiers, Eugène Delacroix)

Battle of Poitiers, 1356

The Battle of Poitiers was a major English victory in the Hundred Year’s War. It was fought on 19 September 1356 in Nouaillé, near the city of Poitiers in Aquitaine, western France. Edward, the Black Prince, led an army of English, Welsh, Breton and Gascon troops, many of them veterans of the Battle of Crécy. They were attacked by a larger French force led by King John II of France, which included allied Scottish forces. The French were heavily defeated; an English counter-attack captured King John II along with his youngest son and much of the French nobility.

The effect of the defeat on France was catastrophic, leaving Dauphin Charles to rule the country. Charles faced populist revolsts across the kingdom in the wake of the battle, which had destroyed the prestige of the French upper-class. The Edwardian phase of the war ended four years later in 1360, on favourable terms for England.

Poitiers was the second major English victory of the Hundred Year’s War. Poitiers was fought ten years after the Battle of Crécy (the first major victory), and about half a century before the third, the Battle of Agincourt (1415). The town and battle were often referred to as Poictiers in contemporaneous recordings.

(Morning of the Battle of Agincourt, 25th October 1415, Sir John Gilbert)

Battle of Agincourt, 1415

The Battle of Agincourt was one of the English victories in the Hundred Year’s War. It took place on 25 October 1415 (Saint Crispin’s Day near Azincourt, in northern France. England’s unexpected victory against the numerically superior French army boosted English morale and prestige, crippled France, and started a new period of English dominance in the war.

After several decades of relative peace, the English had renewed their war effort in 1415 amid the failure of negotiations with the French. In the ensuing campaign, many soldiers died from disease, and the English numbers dwindled; they tried to withdraw to English-held Calais but found their path blocked by a considerably larger French army. Despite the disadvantage, the following battle ended in an overwhelming tactical victory for the English.

King Henry V of England led his troops into battle and participated in hand-to-hand fighting. King Charles VI of France did not command the French army himself, as he suffered from psychotic illnesses and associated mental incapacity. Instead, the French were commanded by Constable Charles d’Albret and various prominent French noblemen of the Armagnac party. This battle is notable for the use of the English longbow in very large numbers, with the English and Welsh archers comprising nearly 80 percent of Henry’s army.

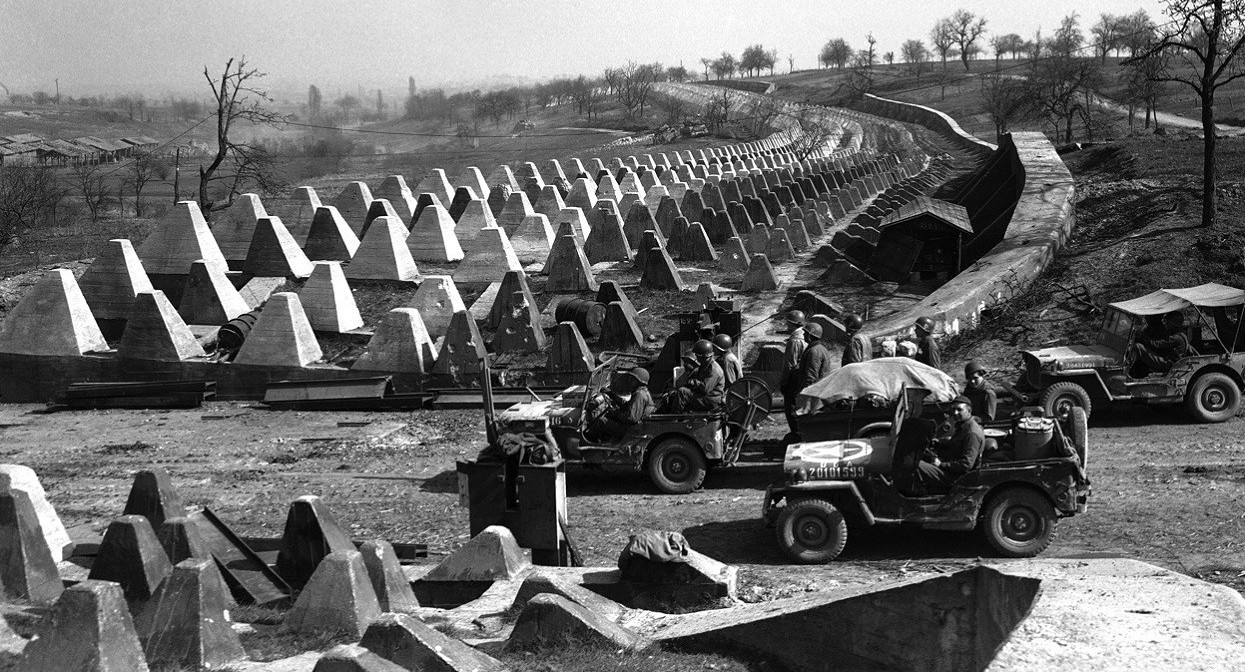

(US Army Photo)

“Dragon’s teeth” concrete tanks traps from the Second World War on the Siegefried Line, Germany.

Early fortifications could be by-passed and “picketed” – a term we use in present day service when a commander directs his mechanized formation of tanks and armoured vehicles to surround and guard a defended enemy position while the rest of the military formation presses on to its objective. In ancient times, the way to prevent a fortress from being outflanked was to build a continuous wall, such as the 400-mile long Limes Germanicus constructed by the Romans across southern Germany in the 2nd century; the Byzantine Wall erected to protect Constantinople; or the more than 5000-mile long Great Wall of China; and the complicated concrete defenses of France’s Maginot Line.[4]

(Jakob Halun Photo)

Great Wall of China, Jinshanling.

The drawbacks to these extended lines of defensive walls were many, including the labor, time and expense required to build them, and more so, the troops required to man them to maintain the defenses which is reason for their construction in the first place. Constant patrolling was required as well as regular rotations of the personnel manning the signal towers and garrisons stationed at intervals along these walls. Eventually, siege techniques were designed to overcome even the most elaborate walls and complexes of fortifications. For practical purposes, early defensive strongpoints evolved to a form of closed ring or “enceinte” to use the French term.

Enceintes protected fortresses, citadels, castles and in some cases entire cities and came to serve as a point of refuge for the population in the surrounding area. The earliest indication of this practice is the stone fortifications which encircled the city of Jericho, which date to about 7000 BC.[5] The Sumerian cities of Ur and Lagash in Mesopotamia have foundations which braced impressive structures dating back to 3500 BC. These buildings rose high above the irrigated flood-plain of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. The Egyptians may have built similar fortifications in the era of the Old Kingdom (2500-1500 BC).[6]

Sargon of Akkad (2371-2316 BC) destroyed the city of Kazalla and made a specific point of wrecking the walls of cities he captured. His warriors rushed the cities gates or they built a sloping rampart of earth as high as the city wall and swarmed over them taking the cities by storm.[7]

Siege of Jericho, ca. 1405/1406 BC

The fortifications at Jericho under the command of a Canaanite, were located on a plain just west of the Jordan River at the site of Tel es-Sultan in present day Israel. In 1405 BC, they were successfully besieged by Hebrew forces under the command of Joshua. The Hebrew destruction of Jericho cleared the first major obstacle to settlement in the “Promised Land”. The twelve tribes of Israel had left Egypt in a mass exodus 40 years earlier. On their approach to Jericho, the Hebrews initially engaged in a battle with the Amorite Kings Sihon and Og, defeating their forces (Joshua 2:9b-10). This victory gave them clear access to the Jordan River north of the Dead Sea. An earthquake blocked the riverbed upstream, facilitating an easy crossing for them.

Joshua sent two of his scouts (spies) into Jericho, even though they should have been visible as the Hebrews would have been within 8 km (5 miles) from the city at their river crossing. They were hidden by an Innkeeper named Rahab and escaped capture. Jericho was a well-established town built around the spring of Ain es-Sultan, in the Plain of Jericho, with excellent crops well-watered, but surrouned by barren land. Modern excavations of the site indicate Jericho was defended by a 4 to 5 metre (1-15 feet) high retaining wall topped with a mud brick wall 7 to 8 metres (20-26 feet) high and 2 metres (6 feet) thick. A second wall of mud bricks was raised outside the retaining wall. Rahab lived between the walls.

Joshua had intructed his soldiers to form up and walk to city’s walls and march around them and then return to the river site. They were to do this for six days, and no sound was to come from the marchers. This may have led the defenders to think they might escape an eventual assault, although each day they manned the walls, prepared for it. The soldiers paraded in full battledress, and carried the Ark of the Covenant in their processions around the walls. The orders changed on the seventh day, and the parade encircled the city walls seven times. The soldiers halted after the last circuit, faced the walls, their priests blew trumpets made of ram’s horns, and all shouted simultaneously. The walls suddenly collapsed, likely due to a well-timed earthquake similar to the one that had dammed the Jordan River the previous week. The crumbled walls would have facilitated easy access to the inner city, which the Hebrews quickly took advantage of putting all in the city to the sword (Joshua 6:20-21).

(Lithograph by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld)

After looting the city of its treasures, the Hebrews burned it. With Jericho destroyed, the Hebrews launched into the remainder of Canaan. Joshua divided the lands his army captured, among the twelve tribes of Israel.

Siege of Lachish, ca. 701 BC

The Assyrian Siege of Lachish led to the conquest of the town in 701 BC. The siege is documented in several sources including the Bible, Assyrian documents and in the Lachish relief, a well-preserved series of reliefs which once decorated the Assyrian king Sennacherib’s palace at Nineveh. Several kingdoms in the Levant ceased to pay taxes for the Assyrina King Sennacherib and as a result he set out on a campaign to re-subjugate the rebelling Kingdoms, among them the Jewish King, Hezekiah. After defeating the rebels of Ekron in Philistia he set out to subjugate Judah and in his way to Jerusalem he came across Lachish, the second most important among the Jewish cities.

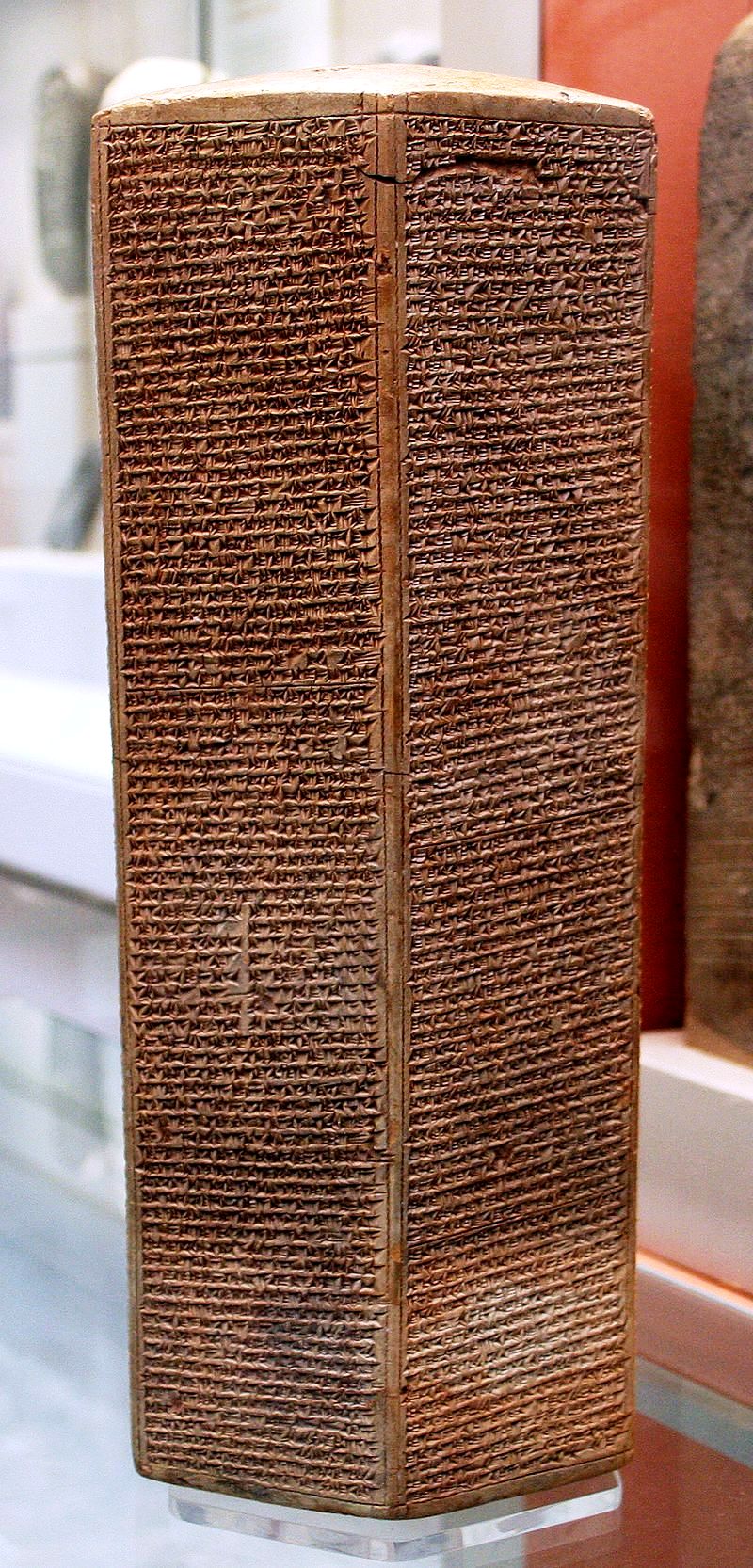

(Wilson44691 Photo)

Lachish front gate, present day remains.

The battlefield was the walled city of Lachish, situated on a hill. The northern part of the hill is steeper than the southern side and due to that the gate is situated there. On top of the fact that the hill as of itself is quite high, the wall further makes the city hard to breach. Inside the city itself there was a castle with significant walls.

The Assyrian Army was the most effective force of its time and was divided mostly into three different categories, Infantry, which included both close-combat troops using spears, and archers. There were also hired mercenaries throwing stones (slingers). The infantry was highly trained and worked alongside military engineers in order to breach sieges. Cavalry; Assyrian cavalry were among the finest in the ancient middle east and included both close-combat cavalry units with spears and mounted archers which could both use the agility of the horses alongside long-range attacks. Chariots, which were not used as much in sieges as in regular land engagements.

The Jewish military force was insignificant compared to the professional and massive Assyrian army and mostly included local militias and mercenaries. There were barely any cavalrymen and chariots in the Jewish army which mostly included infantry, either for close combat (spearmen) or long range combat (archers), they were also significantly less organized.

Due to the steepness of the northern side of Lachish the Assyrian Army attacked from the south, where the Jewish defenders situated themselves on the walls. The Jewish defenders threw stones and shot arrows at the advancing Assyrians; the Assyrians started shooting arrows and stones themselves, creating a skirmish between the two armies. Meanwhile Assyrian military engineers built a ramp to the east of the main gate where Assyrian and Jewish troops began engaging in close combat. The Assyrians meanwhile brought siege engines to the ramp and broke the wall; the Jewish defenders could not hold the Assyrian army and retreated, with some attempting to escape from the other side of the hill.

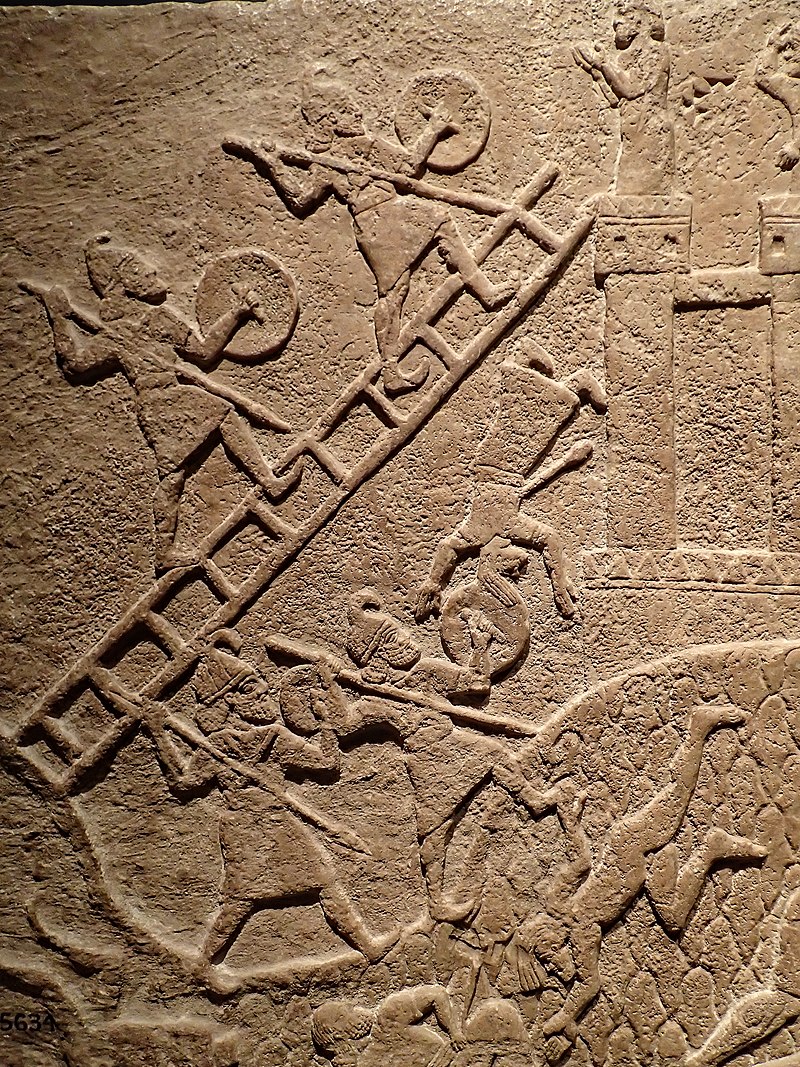

The city was captured by the Assyrians, its inhabitants led into captivity and the leaders of Lachish tortured to death. The town was abandoned, but resettled after the return from Babylonia. Assyrian reliefs portraying the siege of Lachish clearly show battering rams attacking the vulnerable parts of the city. The siege and capture of the town of Lachish, one of the fortress towns protecting the approaches to Jerusalem, is unique in that it is mentioned in the Bible (II Kings 18; II Chronicles 32)( Micah 1:13) and in the Annals of the Assyrian king, Sennacherib.

Illustration of Assyrian relief of Tiglath-Pileser III besieging a town. The British Museum has a set of relief carvings which depict the siege, showing Assyrian soldiers firing arrows, and slingstones, and approaching the walls of Lachish using mudbrick ramps. The attackers shelter behind wicker shields, and deploy battering rams. The walls and towers of Lachish are shown crowded with defenders shooting arrows, throwing rocks and torches on the heads of the attackers. The relief also shows the looting of the city, and defenders being thrown over the ramparts, impaled, having their throats cut and asking for mercy. A bird’s eye plan of the city is shown with house interiors shown in section. After he captured the second most important city in Judah, Sennacherib encamped there and then sent his Rabshakeh (Chief of the Princes) to capture Jerem. (Finkelstein, Israel, and Nadav Na’aman. 2011. The Fire Signals of Lachish: Studies In the Archaeology and History of Israel In the Late Bronze Age, Iron Age)

Assyrian reliefs depicting siege warfare indicate it was in use at least as early as 850 BC, and by that time the basic principles of fortress construction such as making use of loopholes for shooting arrows, curtain walls, crenellation (a pattern along the top of a parapet (fortified wall), most often in the form of multiple, regular, rectangular spaces in the top of the wall, through which arrows or other weaponry may be shot, especially as used in medieval European architecture), parapets (a low protective wall along the edge of a roof, bridge, or balcony), reinforced gates and towers projecting from walls were well understood.=

Siege of Jerusalem, ca. 721 BC

In approximately 701 BCE, Sennacherib, King of Assyria, attacked the fortified cities of Judah, laying siege on Jerusalem, but failed to capture it. In 721 BCE, the Assyrian Army captured the Israelite capital at Samaria and carried away the citizens of the Kingdom of Israel (Samaria) into captivity. The virtual destruction of Israel left the southern kingdom, Judah, to fend for itself among warring Near Eastern kingdoms. After the fall of the Northern Kingdom, the kings of Judah tried to extend their influence and protection to those inhabitants who had not been exiled. They also sought to extend their authority northward into areas previously controlled by the Kingdom of Israel. The latter part of the reign of Ahaz, and most of that of Hezekiah were periods of stability during which Judah was able to consolidate both politically and economically. Although Judah was a vassal of Assyria during this time and paid an annual tribute to the powerful empire, it was the most important state between Assyria and Egypt.

When Hezekiah became king of Judah, he initiated widespread religious changes, including the breaking of religious idols. He re-captured Philistine-occupied lands in the Negev desert, formed alliances with Ashkelon and Egypt, and made a stand against Assyria by refusing to pay tribute. In response, Sennacherib attacked Judah, laying siege to Jerusalem. Sources from both sides claimed victory, the Judahites (or Biblical author(s)) in the Tanakh, and Sennacherib in his prism. Sennacherib claimed the siege and capture of many Judaean cities, but only the siege, not capture, of Jerusalem.

The Hebrew account Sources from both sides claimed victory, the Judahites (or Biblical author(s)) in the Tanakh, and Sennacherib in his prism. Sennacherib claimed the siege and capture of many Judaean cities, but only the siege, not capture, of Jerusalem.

(Assyrian Siege of Jerusalem, Sutori image)

The story of the Assyrian siege is told in the Bible books of Isiah, Chronicles and Second Kings. As the Assyrians began their invasion, Hezekiah began preparations to protect Jerusalem. In an effort to deprive the Assyrians of water, springs outside the city were blocked. Workers then dug a 533-metre tunnel to the Spring of Gihon, providing the city with fresh water. Additional siege preparations included fortification of the existing walls, construction of towers, and the erection of a new, reinforcing wall. Hezekiah gathered the citizens in the square and encouraged them by reminding them that the Assyrians possessed only “an arm of flesh”, but the Judeans had the protection of Yahweh.

According to Second Kings 18, while Sennacherib was besieging Lachish, he received a message from Hezekiah offering to pay tribute in exchange for Assyrian withdrawal. According to the Bible, Hezekiah paid three hundred talents of silver and thirty talents of gold to Assyria, a price so heavy that he was forced to empty the temple and royal treasury of silver and strip the gold from the doorposts of Solomon’s temple. Nevertheless, Sennacherib marched on Jerusalem with a large army. When the Assyrian force arrived, its field commander Rabshakeh brought a message from Sennacherib himself. In an attempt to demoralize the Judeans, the field commander announced to the people on the city walls that Hezekiah was deceiving them, and Yahweh could not deliver Jerusalem from the king of Assyria. He listed the gods of the people thus far swept away by Sennacherib then asked, “Who of all the gods of these countries has been able to save his land from me?”

During the siege, Hezekiah clad himself in sackcloth out of anguish from the psychological warfare that the Assyrians were waging. The prophet Isaiah took an active part in the political life of Judah. When Jerusalem was threatened, he assured Hezekiah that the city would be delivered and Sennacherib would fall. The Hebrew Bible states that during the night, an angel of YHWH brought death to 185,000 Assyrians troops. Hezekiah had shut up all water outside the city so thirst and the fatigue of a long and tiring campaign possibly could have forced the Assyrians to retreat. It is also a possibility that a disease spread throughout the camp and killed a large number of Sennacherib’s men. When Sennacherib saw the destruction wreaked on his army, he withdrew to Nineveh. Jerusalem was spared destruction.

The Bible’s suggestion that Jerusalem was victorious rather than defeated, is corroborated by the Jewish historian Josephus. He quotes Berossus, a well-known Babylonian historian, that a pestilence broke out in the army camp. According to Herodotus, though, field mice chewed at the leather of their weapons and rendered them useless. It is more likely that the mice described by Herodotus were the cause of the pestilence described by Berossus. Nevertheless, as all of these are expansions on the Bible’s account, adding Midrash, none are independent witnesses. In any case, most scholars are in agreement that Sennacherib suffered a humiliating defeat while besieging Jerusalem, and that he went back to Nineveh, never to return. “Like Xerxes in Greece, Sennacherib never recovered from the shock of the disaster in Judah. He made no more expeditions against either the Southern Levant or Egypt.”

(David Castor Photo)

Sennacherib’s Prism, Oriental Institute in Chicago, Illinois.

The Syrian account is taken from Sennacherib’s Prism, which details the events of Sennacherib’s campaign against Judah, was discovered in the ruins of Nineveh in 1830, and is now stored at the Oriental Institute in Chicago, Illinois. The account dates from about 690 BCE. The text of the prism boasts how Sennacherib destroyed forty-six of Judah’s cities, and trapped Hezekiah in Jerusalem “like a caged bird.” The text goes on to describe how the “terrifying splendor” of the Assyrian army caused the Arabs and mercenaries reinforcing the city to desert. It adds that the Assyrian king returned to Assyria where he later received a large tribute from Judah. This description inevitably varies somewhat from the Jewish version in the Tanakh. The massive Assyrian casualties mentioned in the Tanakh are not mentioned in the Assyrian version, but Assyrian government records tend to commonly take the form of propaganda claiming their own invincibility, with the result that they rarely mention their own defeats or heavy casualties. There is speculation that the accounts of mass death among the Assyrian army in the Tanakh might be explained by an outbreak of cholera (or other water-borne diseases) due to the springs beyond the city walls having been blocked, thus depriving the besieging force of a safe water supply.

After he besieged Jerusalem, Sennacherib was able to give the surrounding towns to Assyrian vassal rulers in Ekron, Gaza and Ashdod. His army was still in existence when he conducted campaigns in 702 BCE and from 699 BCE until 697 BCE, when he made several campaigns in the mountains east of Assyria, on one of which he received tribute from the Medes. In 696 BCE and 695 BCE, he sent expeditions into Anatolia, where several vassals had rebelled following the death of Sargon. Around 690 BCE, he campaigned in the northern Arabian deserts, conquering Dumat al-Jandal, where the queen of the Arabs had taken refuge.

When Marduk-apla-iddina continued his rebellion with the help of Elam, in 694 Sennacherib took a fleet of Phoenician ships down the Tigris River to destroy the Elamite base on the shore of the Persian Gulf. While he was doing this the Elamites captured Ashur-nadin-shumi and put Nergal-ushezib, the son of Marduk-apla-iddina, on the throne of Babylon. Nergal-ushezib was captured in 693 BCE and taken to Nineveh, and Sennacherib attacked Elam again. The Elamite king fled to the mountains and Sennacherib plundered his kingdom, but when he withdrew the Elamites returned to Babylon and put another rebel leader, Mushezib-Marduk, on the Babylonian throne. Babylon eventually fell to the Assyrians in 689 BCE after a lengthy siege. (Sayce, Archibald Henry. The Ancient Empires of the East. Macmillan)

A never-ending series of sieges of Jerusalem continiued over many centuries.

Siege of Jerusalem, 597 BC

The first Siege of Jerusalem carried out by Nebuchadnezzar II, King of Babylon, took place in 597 BC. In 605 BC, he defeated Pharaoh Necho at the Battle of Carchemish, and subsequently he invaded Judah. According to the Nebuchadnezzar Chronicle, King Jehoiakim of Judah rebelled against Babylonian rule, but Nebuchadnezzar captured the city and installed Zedekiah as ruler.

To avoid the destruction of Jerusalem, King Jehoiakim of Judah, in his third year, changed allegiances from Egypt to Babylon. He paid tribute from the treasury in Jerusalem, giving up some temple artifacts and some of the royal family and nobility as hostages. In 601 BC, during the fourth year of his reign, Nebuchadnezzar unsuccessfully attempted to invade Egypt and was repulsed with heavy losses. The failure led to numerous rebellions among the states of the Levant which owed allegiance to Babylon, including Judah, where King Jehoiakim stopped paying tribute to Nebuchadnezzar and took a pro-Egyptian position. Nebuchadnezzar soon dealt with these rebellions. According to the Nebuchadnezzar Chronicle, he laid siege to Jerusalem, which eventually fell on 2 Adar (16 March 597 BC).

The Chronicle states: In the seventh year [of Nebuchadnezzar, 598 BC] in the month Chislev [November/December] the king of Babylon assembled his army, and after he had invaded the land of Hatti (Syria/Palestine) he laid siege to the city of Judah. On the second day of the month of Adar [16 March] he conquered the city and took the king [Jeconiah] prisoner. He installed in his place a king [Zedekiah] of his own choice, and after he had received rich tribute, he sent forth to Babylon.

Jehoiakim died during the siege, possibly on 22 Marcheshvan (10 Dec 598 BC), or during the months of Kislev, or Tevet. Nebuchadnezzar pillaged the city and its Temple, and the new king Jeconiah, who was either 8 or 18, and his court and other prominent citizens and craftsmen, and much of the Jewish population of Judah, numbering about 10,000 were deported to Babylon. The deportation occurred prior to Nisan of 597 BC, and dates in the Book of Ezekiel are counted from that event. A biblical text reports, “None remained except the poorest people of the land”. Also, taken to Babylon were the treasures and furnishings of the Temple, including golden vessels dedicated by King Solomon. (2 Kings 24:13-14)

The events are described in the Nevi’im and Ketuvim sections of the Old Testament. The first deportation was the beginning of the Jewish Diaspora (or exile). (2 Kings 24:10-16) Nebuchadnezzar installed Jeconiah’s uncle, Zedekiah as a puppet-king of Judah, and Jeconiah was compelled to remain in Babylon. The start of Zedekiah’s reign has been variously dated within a few weeks before, or after the start of Nisan 597 BC. (Horn, Siegfried H. The Babylonian Chronicle and the Ancient Calendar of the Kingdom of Judah. Andrews University Seminary Studies, V 1)

Siege of Jerusalem, 589 BC

The second Siege of Jerusalem carried out by Nebuchadnezzar II, King of Babylon began in 589 BC. In 586 BC, after completion of the eleventh year of Zedekiah’s reign, Nebuchadnezzar broke through Jerusalem’s walls, conquering the city. After the fall of Jerusalem, the Babylonian general, Nebuzaraddan, was sent to complete its destruction. Jerusalem was plundered, and Solomon’s Temple was destroyed in the summer of 587 or 586 BC. The city was razed to the ground, and only a few people were permitted to remain to tend to the land. Zedekiah and his followers attempted to escape but were captured on the plains of Jericho and taken to Riblah. There, after seeing his sons killed, Zedekiah was blinded, bound, and taken captive to Babylon, where he remained a prisoner until his death. (2 Kings 25:1-7, Chronicles 36:12, and Jeremiah 32:4-5)

Siege of Sardis, 547 BC

The Siege of Sardis (547-546 BC), was the last decisive conflict after the Battle of Thymbra, which was fought between the forces of Croesus of Lydia and Cyrus the Great, when Cyrus followed Croesus to his city. He laid siege to it for 14 days, and then captured it.

In the previous year King Croesus of Lydia, impelled by various considerations, invaded the kingdom of Cyrus the Great, hoping to quell the growing power of Achaemenid Persia; to expand his own dominions; and revenge the deposition of his brother-in-law Astyages. He thought he was certain of success, deluded by the ambiguous assurances of the apparently reliable oracle of Apollo at Delphi. Croesus crossed the Halys and met Cyrus at Pteria in Cappadocia, but after a drawn-out battle against superior forces in which neither side obtained the victory Croesus resolved to fall back for the winter, summon new allies, and renew the war reinforced in the next spring. In the interim, he disbanded his army and returned to Sardis, expecting Cyrus to hang back after the sanguinary battle in Cappadocia. But the energetic Cyrus,as soon as he heard that Croesus’ forces were dispersed, crossed the Halys and advanced with such speed that he had arrived at the Lydian capital, Sardis, before Croesus had any word of his approach. Undaunted, Croesus mustered his availible troops and met Cyrus in the Battle of Thymbra outside the walls. Cyrus was victorious, having contrived to deprive the Lydians of their last resource, their cavalry (in which the Lydians allegedly surpassed all other nations at the time), by frightening off their horses with the sight of his camels. The remnants of the Lydian army were driven within the city and promptly besieged.

Croesus was still confident in his chances because Sardis was a well-fortified city consecrated by ancient prophecies to never be captured. Additionally, he had sent for immediate aid from Sparta, the strongest state in Greece and his firm ally, and he hoped to enlist the Egyptians, the Babylonians and others in his coalition against Persia as well. Unfortunately for him, the Spartans were then occupied in a war with neighboring Argos, and neither they nor any other of Croesus’ allies would assemble in time.

Cyrus offered large rewards to the first soldiers who should ascend the battlements (top of a protective wall); but repeated Persian attacks were repulsed with loss. According to Herodotus, the city ultimately fell by the agency of a Persian soldier, who climbed up a section of the walls which was neither adequately garrisoned, nor protected by the ancient rites which had dedicated the rest of the cities’ defenses to impregnability; the steepness of the adjoining ground outside the walls was responsible for this piece of Lydian Hubris. Hyroeades, the Persian soldier, saw a Lydian soldier climbing down the walls to retrieve a dropped helmet, and tried to follow the example. The success of his ascent set the example to the rest of Cyrus’ soldiers and these swarming over the exposed wall and the city was promptly taken.

Cyrus had previously issued orders for Croesus to be spared, and the latter was hauled a captive before his exulting foe. Cyrus’ first intentions to burn Croesus alive on a pyre were soon diverted by the impulse of mercy for a fallen foe, and according to ancient versions, by divine intervention of Apollo, who caused a well-timed rainfall. Tradition represents the two kings as reconciled thereafter; Croesus succeeded in preventing the worst rigors of a sack by representing to his captor that it was his, not Croesus’ property being plundered by the Persian soldiery.

The kingdom of Lydia came to an end with the fall of Sardis, and her subjection was confirmed in an unsuccessful revolt in the following year, promptly crushed by Cyrus’ lieutenants. The Aeolian and Ionian cities on the coast of Asia Minor, formerly tributaries of Lydia, were likewise conquered not long after, establishing the circumstances for Greco-Persian animosity, which would last till the outbreak of the Persian Wars in the succeeding century. (Herodotus. The Histories, Penguin Books, 1983)

Siege of Naxos, 499 BC

The Siege of Naxos (499 BC) was a failed attempt by the Milesian tyrant Aristagoras, operating with support from, and in the name of the Persian Empire of Darius the Great, to conquer the island of Naxos. It was the opening act of the Greco-Persian Wars, which would ultimately last for 50 years.

Aristagoras had been approached by exiled Naxian aristocrats, who were seeking to return to their island. Seeing an opportunity to bolster his position in Miletus, Aristagoras sought the help of his overlord, the Persian king Darius the Great, and the local satrap, Artaphernes to conquer Naxos. Consenting to the expedition, the Persians assembled a force of 200 triremes under the command of Megabates.

The expedition quickly descended into a debacle. Aristagoras and Megabates quarreled on the journey to Naxos, and someone (possibly Megabates) informed the Naxians of the imminent arrival of the force. When they arrived, the Persians and Ionians were thus faced with a city well prepared to undergo siege. The expeditionary force duly settled down to besiege the defenders, but after four months without success, ran out of money and were forced to return to Asia Minor.

In the aftermath of this disastrous expedition, and sensing his imminent removal as tyrant, Aristagoras chose to incite the whole of Ionia into rebellion against Darius the Great. The revolt then spread to Caria and Cyprus. Three years of Persian campaigning across Asia Minor followed, with no decisive effect, before the Persians regrouped and made straight for the epicentre of the rebellion at Miletus. At the Battle of Lade, the Persians decisively defeated the Ionian fleet and effectively ended the rebellion. Although Asia Minor had been brought back into the Persian fold, Darius vowed to punish Athens and Eretria, who had supported the revolt. In 492 BC therefore, the first Persian invasion of Greece, would begin as a consequence of the failed attack on Naxos, and the Ionian Revolt. (Herodotus. The Histories, Penguin Books, 1983)

Siege of Eretria, 490 BC

The Siege of Eretria took place in 490 BC, when the city of Eretria on Euboea was besieged by a strong Persian force under the command of Datis and Artaphernes. The siege lasted six days before a fifth column of Eretrian nobles betrayed the city to the Persians. The city was plundered, and the population enslaved on Darius’s orders. The Eretrian prisoners were eventually taken to Persia and settled as colonists in Cissia.

After Eretria, the Persian force sailed for Athens, landing at the bay of Marathon. An Athenian army marched to meet them, and won a famous victory at the Battle of Marathon, thereby ending the first Persian invasion. (Herodotus. The Histories, Penguin Books, 1983)

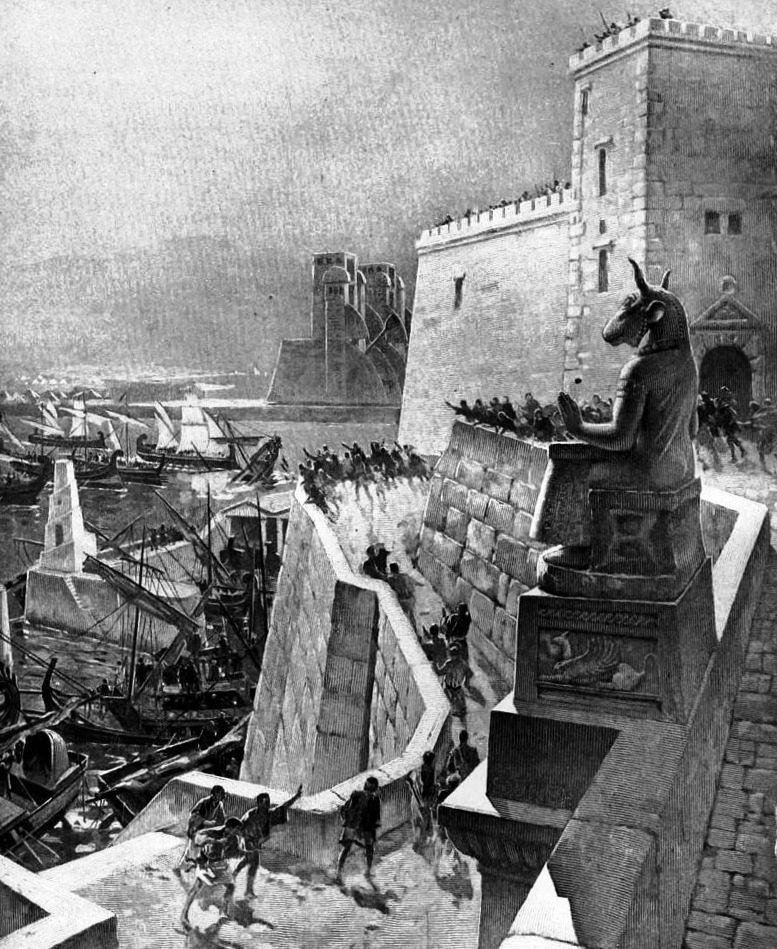

Siege of Syracuse, 397 BC

The Siege of Syracuse in 397 BC was the first of four unsuccessful sieges Carthaginian forces would undertake against Syracuse from 397 to 278 BC. In retaliation to the Siege of Motya by Dionysius of Syracuse, Himilco of the Magonid family of Carthage led a substantial force to Sicily. After retaking Motya and founding Lilybaeum, Himilco sacked Messana, then laid siege of Syracuse in the autumn of 397 BC after the Greek navy was crushed at Catana.

The Carthaginians followed a strategy which the Athenians had used in 415 BC, and were successful in isolating Syracuse. A pestilence broke out in the Carthaginian camp in the summer of 396 BC, which killed the majority of the troops. Dionysius launched a combined land and sea attack on the Carthaginian forces, and Himilco escaped with the Carthaginian citizens after an underhand deal with Dionysius. The surviving Libyans were enslaved, the Sicels melted away while the Iberians joined Dionysius. Dionysius began expanding his domain, while Carthage, weakened by the plague, took no action until 393 BC against Syracusan activities. (Kern, Paul B. Ancient Siege Warfare. Indiana University Publishers. 1999)

Siege of Pelium, 335 BC

The Siege of Pelium was undertaken by Alexander the Great against the Illyrian tribes of what is modern-day Albania. It was critical for Alexander to take this pass as it provided easy access to Illyria and Macedonia, which was urgently needed in order to quell the unrest in Greece at this time in Athens and Thebes. This was an important point of demarcation in Alexander’s early reign, as it established him among the Danubian tribes to the north as a serious monarch to be reckoned with, just as he would later establish this precedent for the Greek city states under his hegemony. Taking this place allowed Alexander to march his army to southern Greece quickly, which would eventually result in the total destruction of Thebes.

News of the Illyrian revolt under Cleitus the Dardanian, and King Glaukias of the Taulantii first reached the ears of Alexander while he was campaigning on the Danube against some of the northern tribes that his father, Philip II of Macedon had previously reduced to a satisfactory level of subjection, although not outright submission. As this area had been far from the Greek theatre of operations, Phillip had been satisfied with the level of subjection he had reduced them to.

Alexander was immediately concerned about the news of this revolt, as the settlement of Pelium itself occupied one of the most important passes between Illyria and Macedonia. As a result of this, Alexander would have to make a long march around a mountain range to the south, and then into Illyria. In addition to this, without access to this crucial pass, Alexander could be cut off from Greece, which had freshly revolted, and would eventually do so again, with aid of the Great King. The loss of this pass, and the resultant long march would give the Greek city states to the south ample time to prepare for Alexander’s arrival while he was reducing the Illyrians.

An ally of Alexander offered aid to him by protecting his flank from Illyrian tribes while he marched towards Pelium. Langarus, of the Agrianians, made frequent incursions into the country of the Autariatae, and managed to put them on guard sufficiently to allow Alexander to march by in relative peace. Having successfully made this march, Alexander arrived to find Cleitus the Dardanian in control of Pelium and awaiting the arrival of King Glaukias with reinforcements. When Alexander arrived, Cleitus reportedly sacrificed three boys, three girls, and three black rams before meeting the Macedonians.

Alexander arrived with 15,000 soldiers and determined to attack Pelium at once, as he hoped to take the place out of hand before King Glaukias could arrive and reinforce Cleitus. The first thing Alexander did upon arriving was set up the Macedonian camp. The Macedonians found that not only was Pelium itself held, which commanded the plateau, but the heights surrounding the Plain of Pelium was held in force. Upon completing the camp, Alexander resolved to attack the troops of Cleitus that were surrounding the heights. This he did with some effect, and as a result of this assault the Illyrians retreated within the walls of Pelium. Alexander then attempted to take the town by assault, but failing in this, he started to erect circumvallation (a line of fortifications, built by the attackers around the besieged fortification facing towards an enemy fort, designed to protect the besiegers from sorties by its defenders and to enhance the blockade), and contravallation (a second line of fortifications outside the circumvallation, facing away from an enemy fort. The contravallation protects the besiegers from attacks by allies of the city’s defenders and enhances the blockade of an enemy fort by making it more difficult to smuggle in supplies), around Pelium. This, however, was interrupted by the arrival of Glaukias and his reinforcements the next day, which compelled Alexander to retreat from the heights that he had captured the day before.

Having been forced back into the plain itself by King Glaukias, Alexander was in now a perilous situation. He was outnumbered by the Illyrians, who were free to gather supplies. Not only that, but Alexander was anxious to take Pelium quickly before Thebes and Athens could seriously consider imperiling Macedonian hegemony. Therefore, not only did Alexander have pressing issues elsewhere, but the Illyrian forces were determined to annihilate Alexander’s forces, and could afford to wait.

Being short of supplies, Alexander sent Philotas, one of his lieutenants, out to forage for materials. King Glaukias witnessed this force leaving, and pursued and attacked the foragers. H owever, Alexander was, with some difficulty, able to fend off the attackers and extricate his hypaspists, Agrianians and bowmen.

Seeking to seize his line of retreat before putting his shoulder to the siege, Alexander decided to attack the heights that commanded the defile through which he had come. This defile was small, and only four men could march through it abreast. He drew up some of his infantry and cavalry in front of the settlement of Pelium itself to defend this maneuver from being attacked by a sortie from Cleitus. He then drew up his phalanx, one hundred and twenty men deep, with 200 cavalry on either flank, and arranged his soldiers to perform close-order drills down on the plain, in full view of the Illyrians, in complete silence. As Peter Green describes:

“At given signals the great forest of sarissas would rise to the vertical ‘salute’ position, and then dip horizontally as for battle-order. The bristling spear-line swung now right, now left, in perfect unison. The phalanx advanced, wheeled into column and line, moved through various intricate formations as though on the parade-ground – all without a word being uttered. The barbarians had never seen anything like it. From their positions in the surrounding hills they stared down at this weird ritual, scarcely able to believe their eyes. Then, little by little, one straggling group after another began to edge closer, half-terrified, half-enthralled. Alexander watched them, waiting for the psychological moment. Then, at last, he gave his final pre-arranged signal. The left wing of the cavalry swung into wedge formation, and charged. At the same moment, every man of the phalanx beat his spear on his shield, and from thousands of throats there went up the terrible ululating Macedonian war-cry – ‘Alalalalai!’ – echoing and reverberating from the mountains. This sudden, shattering explosion of sound, especially after the dead stillness which had preceded it, completely unnerved Glaucias’ tribesmen, who fled back in wild confusion from the foothills to the safety of their fortress.” (Green, Peter, Alexander of Macedon, 356-323 B.C. University of California Press, 1991)

The Macedonian forces took the heights overlooking Pelium. During this engagement, not a single Macedonian armored soldier was killed. However, deaths among light troops were usually not reported, and it is unknown whether any were killed in this instance.

There were still some Illyrian light infantry on the heights that commanded the ford, and it was critical for Alexander to seize these heights in order to gain control of the entire plain. Before engaging in battle, Alexander decided to re-establish his camp on the far side of the river near the ford in order to ensure the security of both his operations and his camp. However, in the process of doing so he ran the danger of being engaged in the rear while his troops were crossing the river. The Illyrians indeed attacked him, perceiving his army to be retreating. So he ordered his troops to turn around to simulate an advance, while initiating a charge with his companion cavalry. Meanwhile, he also ordered his archers to turn around and fire their arrows from mid-stream. Having gained a place of relative security on the far side of the river, Alexander was able to freely supply his army and await reinforcements. Before reinforcements arrived, however, Macedonian scouts reported that they observed the Illyrians becoming careless in protecting the settlement, as they thought Alexander was in retreat.

Acting on this intelligence, Alexander awaited the arrival of night, and then rushed ahead without awaiting the crossing of his complete force, leading his archers, his shield-bearing guards, the Agrianians, and the brigade of Coenus as the leading unit. He then rushed down upon the defenders with his Agrianians and archers, who were formed in phalanx formation. Many of the Illyrians were still asleep, and were taken completely by surprise. A great slaughter followed; many of the Illyrians were also captured.

As a result of this siege, Alexander gained Pelium, and built a fresh outpost there, as the Illyrians had burnt the settlement that had previously been situated there. The Illyrians begged for terms, and Alexander was happy to accept their submission and allow them to swear fealty to him anew. Having completed his conquest, Alexander had established himself as a new monarch to be revered, and was now free to march south to Boeotia and deal with the threat from Thebes and Athens. (Dodge, Theodore Alexander. New York, NY: Da Capo, 1890).

Topographical map of the Aegean area in c.500 BC, showing major events of the Ionian Revolt.

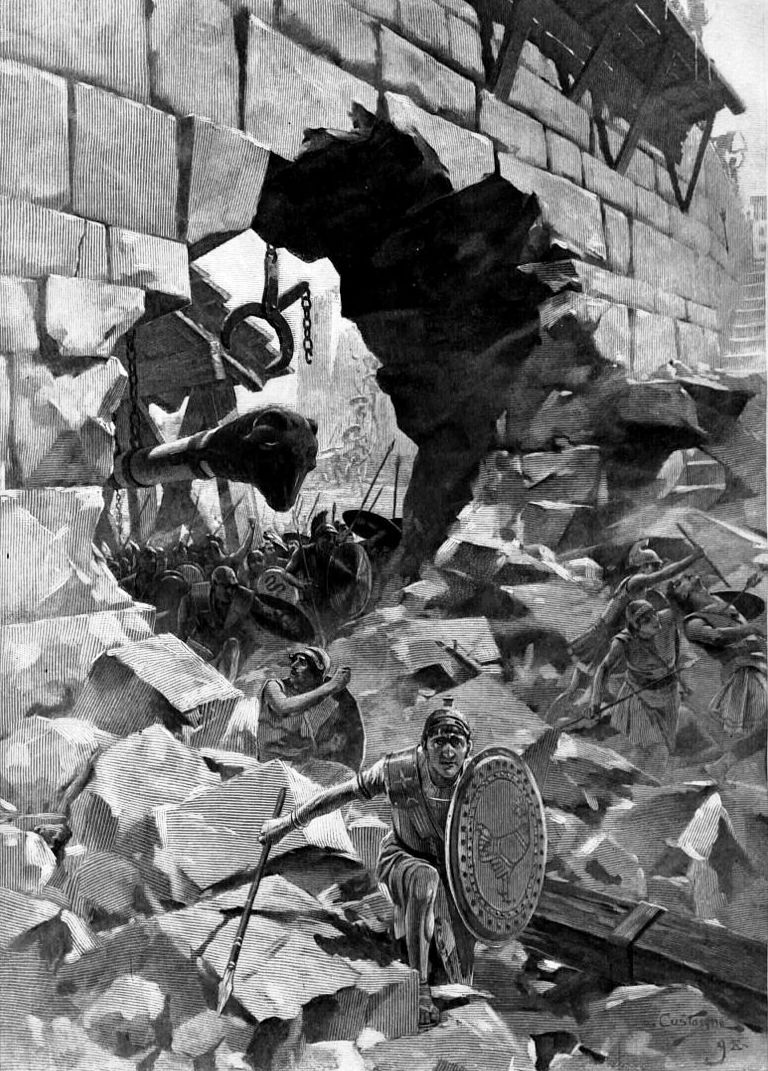

Siege of Miletus, 334 BC

The Siege of Miletus was Alexander the Great’s first siege and naval encounter with the Achaemenid Empire. This siege was directed against Miletus, a city in southern Ionia, which is now located in the Aydin province of modern-day Turkey. It was captured by Parmenion’s son, Nicanor in 334 BC.

(The capture of Miletus, engraving by Andre Castaigne)

Siege of Halicarnassus, 334 BC

The Siege of Halicarnassus was fought between Alexander the Great and the Achaemenid Persian Empire in 334 BC. Alexander, who had no navy, was constantly being threatened by the Persian Navy. It continuously attempted to provoke an engagement with Alexander, who would not oblige them. Eventually, the Persian fleet sailed to Halicarnassus, in order to establish a new defense. Ada of Caria, the former queen of Halicarnassus, had been driven from her throne by her younger brother Pixodarus of Caria. When Pixodarus died, Persian King Darius had appointed Orontobates satrap of Caria, which included Halicarnassus in its jurisdiction. On the arrival of Alexander in 334 BC, Ada, who was in possession of the fortress of Alinda, surrendered the fortress to him.

Orontobates and Memnon of Rhodes entrenched themselves in Halicarnassus. Alexander had sent spies to meet with dissidents inside the city, who had promised to open the gates and allow Alexander to enter. When his spies arrived, however, the dissidents were nowhere to be found. A small battle resulted, and Alexander’s army managed to break through the city walls. Memnon, however, now deployed his catapults, and Alexander’s army fell back. Memnon then deployed his infantry, and shortly before Alexander would have received his first defeat, his infantry managed to break through the city walls, surprising the Persian forces. Memnon, realizing the city was lost, set fire to it and withdrew with his army. Strong winds caused the fire to destroy much of the city.

Alexander committed the government of Caria to Ada; and she, in turn, formally adopted Alexander as her son, ensuring that the rule of Caria passed unconditionally to him upon her eventual death. During her husband’s tenure as satrap, Ada had been loved by the people of Caria. By putting Ada, who felt very favorably towards Alexander, on the throne, he ensured that the government of Caria, as well as its people, remained loyal to him. (Cartledge, Paul. Alexander the Great: The Hunt for a New Past. Woodstock, NY; New York: The Overlook Press, 2004)

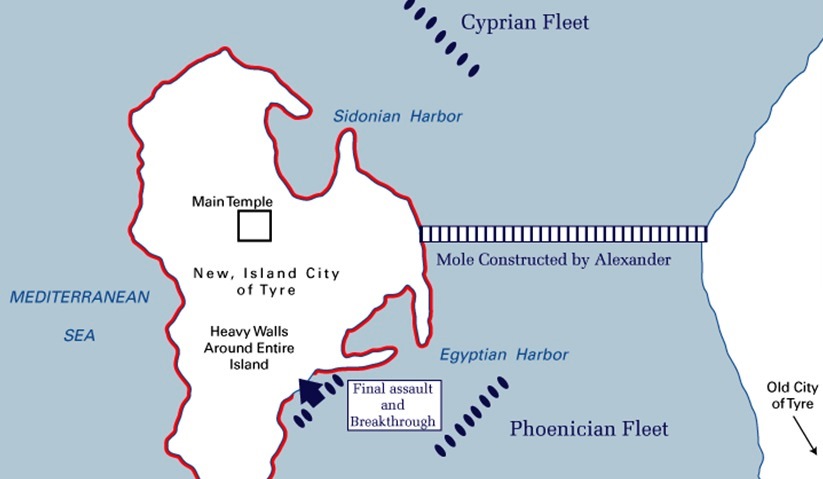

Siege of Tyre, 332 BC

Island fortifications pose a number of logistical siege difficulties for an attacker. In 332 BC, Alexander the Great chose to conduct an attack against the important island of Tyre, sited roughly half a mile off shore.[51] This island was protected by high, two-mile long wall constructed of heavy stone, which ran around it, and also protected by a strong navy.

French Air Force photo of Tyre, 1934.

Naval Action during the Siege of Tyre.

Tyre was of strategic importance to Alexander the Great.[52] He initially attempted to seize it by subterfuge, claiming he wished to enter Tyre in order to sacrifice to Heracles. At that time, Alexander was convinced that once Tyre was his, all the Phoenician ships would desert the Persian king and come over to his side. Confident in the fortifications of their island city, the Tyrians objected. Alexander prepared a plan of siege that involved joining the island fortress to the mainland by an artificial isthmus, thus turning Tyre into a peninsula over which he could bring his powerful siege engines up to the city’s walls. [53]

Map of the Siege of Tyre, Nov 333 to Aug 332 BC.

During the 7-month long siege which followed, Alexander had his engineers construct a causeway to the island. A strait of four “stadia” separated the island city from the mainland and it was exposed to southwest winds. Alexander ordered large stones and tree trunks from the mountains of Lebanon to be brought down to the coast and cast into the sea. As long as the building of the mole went on near the mainland, the work went on smoothly, but as his men went into deeper water and came closer to the city, they came under a volley of arrows shot by archers positioned on the walls. At the same time, the Tyrian sent warships which sailed up on either side of the workers, mocking and harassing them. This causeway was destroyed several times before Alexander finally succeeded. In order to do so, Alexander eventually came to understand that the island couldn’t be taken unless he had ships to counter the Tyrian navy and enable him to control the sea.

Alexander ordered two towers to be built on the mole and had them equipped with siege engines. The towers were covered with hides and skins so they could withstand fire darts launched by the Tyrians. In response, the Tyrians filled a large horse-carrying transport ship with dry boughs and other combustible materials. They fixed two masts on the ship’s prow, each with a projecting arm from which was suspended a cauldron filled with bitumen, sulphur and other highly inflammable materials. The stern of the vessel was loaded with stone and sand, which in turn elevated the bow so that it could be easily driven over the mole to reach Alexander’s towers. The Tyrians then waited for a favorable wind to blow towards the mole, and when it came, they towed the ship towards their target from astern with triremes. After running the “fire-ship” at full speed upon the mole, they then set the combustible materials on fire with torches. The ship was dashed violently against the mole and the cauldrons scattered the fiery mass in all directions, while the crew of the burning ship swim away to safety.

On hearing that their cities had fallen into Alexander’s hands, the kings of Aradus and Byblos, deserted the Persian cause and sailed their fleets to Tyre. When they arrived at the site of the siege with their armed contingents and Sidonian triremes, the offered to join with Alexander. When the kings of Cyprus learned that their enemy Darius has been defeated at Issus by Alexander, they also decided to join him and sailed to Sidon with 120 ships. Additional Triremes arrived from Rhodes, Soli, Mallos, and Lycia along with a fifty-oar ship from Macedon. The chronicler Arrian (2.20.3) records the following: “To all these Alexander let bygones be bygones supposing that it was rather from necessity than choice that they had joined naval forces with the Persians.”

While this impressive fleet was being prepared for battle with the Tyrians and his siege engines were being fitted to make the final assault, Alexander took a detachment of archers and heavy cavalry (the “hypasists”) and marched into Sidon, where he launched a ground attack which conquered part of the country and caused others to readily surrender. He also managed to seized or collect 120 triremes. When Alexander’s fleet hove into view off the coast of the island under siege, the Tyrians refused to fight, permitting the Macedonians to attack the wall without seaward interference.

Realizing Alexander now had his back protected, and the seaward approaches were almost fully in his hands, the Tyrians decided to go on the offensive before Alexander attacked. Their plan was to sink the enemy fleet, including the ships of their sister-cities. This would be difficult to put into effect, because the ships from Cyprus blocked the mouth of the Tyrian “Sidonian” port, so-called because it faced north towards Sidon. In order to conceal their plans and preparations, the Tyrians spread out sails in front of the entrance to the harbor. Waiting until midday when they had determined the Cypriot sailors were not on their guard, the Tyrians set sail with their most effective sea fighting men and attacked the surprised enemy, sinking several ships.

Alexander was infuriated by this setback, and ordered his ships to immediately blockade the Tyrian harbor before the raiders escaped. The Tyrian defenders manning the fortresses walls vainly shouted and gestured to the raiders to turn back. Wheeling their ships about, the Tyrians attempted to sail back to the protection of their harbor. Only a few manage to get to safety but Alexander’s naval forces put most of the rest out of action. A handful of the Tyrian crews succeeded in jumping overboard and swimming to land. The end result of this abortive naval sally was a victory for Alexander, which allowed him to bring his Macedonian closer to Tyre’s city walls.

Shortly after this naval engagement, Alexander had his battering rams brought forward and pressed up against the fortresses north walls. As the war machines drew closer to walls, the attackers discovered the fortifications on the mole were too high for the Macedonians to scale. This forced Alexander to turn south to the “Egyptian” port, so-called because it faced Egypt, while testing the strength of the Tyrian walls along the way. Here he discovered a part of the city’s fortifications had broken down. He immediately threw a series of siege bridges over the walls, but the Tyrian defenders repulsed the attack.

Alexander reportedly had a dream that Tyre would fall to him, and as a result, he launched his final assault on the fortress. He ordered his triremes to sail against both the “Sidonian” and “Egyptian” ports simultaneously, with object being to force an entrance. They succeeded in gaining access to both harbors and captured the Tyrian ships. Alexander’s ships then closed in on the city from all sides and when they were close enough, siege bridges were thrown over the walls from his vessels. Macedonian soldiers quickly ran across the siege bridges, and advanced through breaches in the walls where they engaged and quickly dispatched or fought off the Tyrian defenders.

During the siege, as the Macedonians attacked the wall, the Tyrians poured hot liquids and sand onto the attackers causing severe burns. A large number of Tyrians deserted the walls and barricaded themselves in the Shrine of Agenor. The people of Tyre particularly revered this monument for, in legendary tradition, Agenor was their king, the father of Cadmus and Europa. According to the chronicler Arrian (2.24.2), Alexander’s bodyguards found and attacked them here killing them all in a bloody massacre. The Macedonians had been infuriated by the Tyrian treatment of their captured companions. When Alexander’s men had sailed from Sidon to engage the Tyrians in the earlier sea-battles, the Tyrians had captured a number. These men were dragged up on the fortress walls and executed in full view of Alexander’s forces. Their bodies were then flung into the sea. Seeing themselves at last masters of the city, Alexander’s bodyguard were determined to avenge the death of their companions, and gave no mercy to the Tyrians they held responsible for the murders. It is recorded that a total of 8,000 Tyrians died, with only 400 Macedonians lost in the siege.[54]

The historian Quintus Curtius (4.2.10-12) records that at this time a Carthaginian delegation was in Tyre to celebrate the annual festival of Melkart-Heracles. The king of Tyre, Azemilcus, the chief magistrates and the Carthaginian embassy took refuge in the temple of Heracles. Alexander granted them a full pardon but he severely punished the people of Tyre. Some 30,000 were sold into slavery. According to Quintus Curtius (4.4.17), 2,000 Tyrians were nailed to crosses along a great stretch of the shore.

Alexander offered a sacrifice to Heracles and held a procession of his armed forces in the city. He also ensured that a naval review was held in the god’s honor. The Tyrians had chained a statue of their deity Apollo to keep him from deserting them. Alexander therefore solemnly supervised the removal of these golden chains and fetters from Apollo and ordered that henceforth the god be called Apollo “Philalexander.” He rewarded those of his men who had distinguished themselves and gave a lavish funeral for his dead. Having completed the successful siege of Tyre, Alexander moved on, and with the fall of Gaza to the south, he headed on to Egypt.[55]

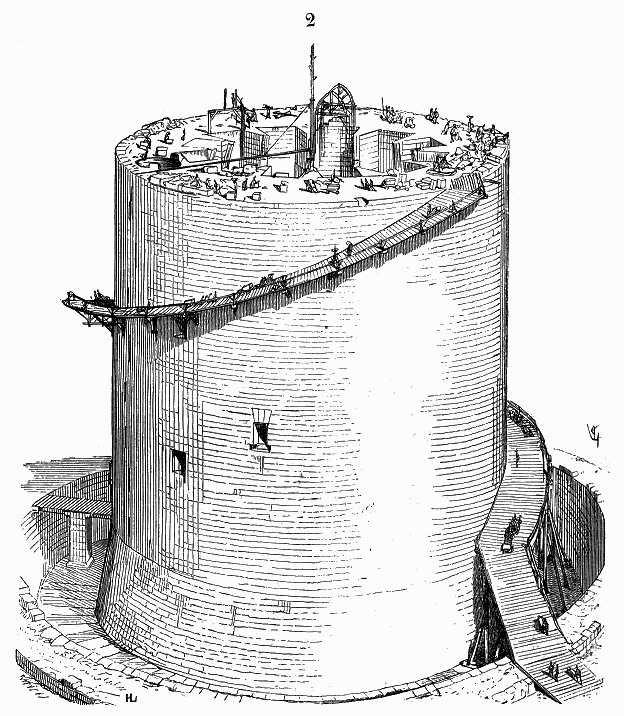

Stone Towers, Keeps and Donjons

Although many medieval fortresses consisted of castles rather than of town walls (many of which were built over foundations and stonework dating back to Roman times), there were very few new elements added. Medieval castles were generally centered on massive stone towers, keeps ( a type of fortified tower built within castles), or donjons. These were often surrounded by multiple layers of curtain walls (the outer wall of a castle or defensive wall between two bastions), that had covered galleries, buttresses, parapets, crenellation, machicolations, flanking towers, sally ports, and protected gates incorporated into their design and construction.

The designs evolved continuously over the lifetime of each fortress or castle, with ditches and moats being added where possible, particularly in Northwestern Europe because of the abundance of water. The primary difference in medieval castles over their primitive predecessors was their function. A castle was used to dominate the countryside it surveyed, which meant many were sited on strategically chosen spurs of hills overlooking all approaches, which gave additional warning and protection. To overcome them, an attacker had to be inventive and utilize increasingly sophisticated methods of siegecraft and siege engines.

(David Perez Photo)

Castle of Arévalo (Castillo de Arévalo), built between the 12th and 16th centuries in the north of the province of Avila in Spain. The ground plan is almost square, round towers at its corners, round sentry boxes on its walls and the large D-shaped keep in one corner. The keep is made of ashlar masonry with later brick additions similar to the rest of the castle.

(Edal Anton Lefterov Photo)

Château de Vincennes, a massive 14th and 17th century French royal fortress in the town of Vincennes, to the east of Paris. It was constructed for Louis VII about 1150 in what was then a forest of Vincennes. In the 13th century, Philip Augustus and Louis IX erected a more substantial manor. Louis IX is reputed to have departed from Vincennes on the crusade from which he did not return. To strengthen the site, the castle was greatly enlarged replacing the earlier site in the later 14th century. A donjontower, 52 meters high, the tallest medieval fortified structure of Europe, was added by Philip VI of France, a work that was started about 1337. The grand rectangular circuit of walls, was completed by the Valois about two generations later (ca. 1410). The donjon served as a residence for the royal family, and its buildings are known to have once held the library and personal study of Charles V. Henry V of England died in the donjon in 1422 following the siege of Meaux.

At the end of February 1791, a mob of more than a thousand workers marched out to the château, which, rumour had it, was being readied on the part of the Crown for political prisoners, and with crowbars and pickaxes set about demolishing it. The work was interrupted by the Marquis de Lafayette who took several ringleaders prisoners, to the jeers of the Parisian workers. It played no part during the remainder of the Revolution. From 1796, it served as an arsenal. The execution of the duc d’Enghien took place in the moat of the château on 21 March 1804.

(General Daumesnil, “Je rendrai Vincennes quand on me rendra ma jambe”, from a painting by Gaston Mélingue).

General Daumesnil who lost a leg at the Battle of Wagram (5–6 July 1809), was assigned to the defence of the château de Vincennes in 1812. Vincennes was then an arsenal containing 52,000 new rifles, more than 100 field guns and many tons of gunpowder, bullets, canonballs. It was a tempting prize for the Sixth Coalition marching on Paris in 1814 in the aftermath of the Battle of the Nations. However, Daumesnil faced down the allies and replied with the famous words “Je rendrai Vincennes quand on me rendra ma jambe” (“I shall surrender Vincennes when I get my leg back”). With only 300 men under his command, he resisted the Coalition until King Louis XVIII ordered him to leave the fortress.

Vincennes also served as the military headquarters of the Chief of General Staff, General Maurice Gamelin, during the unsuccessful defence of France against the invading German army in 1940. It is now the main base of France’s Defence Historical Service, which maintains a museum in the donjon. On 20 August 1944, during the battle for the Liberation of Paris, 26 policemen and members of the Resistance arrested by soldiers of the Waffen SS were executed in the eastern moat of the fortress, and their bodies thrown in a common grave.

Only traces remain of the earlier castle and the substantial remains date from the 14th century. The castle forms a rectangle whose perimeter is more than a kilometer in length (330 x 175m). It has six towers and three gates, each originally 13 meters high, and is surrounded by a deep stone lined moat. The keep, 52m high, and its enceinte occupy the western side of the fortress and are separated from the rest of the castle by the moat. The keep is one of the first known examples of rebar usage. The towers of the grande enceinte now stand only to the height of the walls, having been demolished in the 1800s, save the Tour du Village on the north side of the enclosure. The south end consists of two wings facing each other, the Pavillon du Roi and the Pavillon de la Reine, built by Louis Le Vau. The castle was one of the first buildings in history to use steel to reinforce the walls. (Jean Mesqui, Châteaux forts et fortifications en France. Paris: Flammarion, 1997)

(Selbymay Photo)

Château de Vincennes.

Engraving of Echafaud donjon, Coucy, France, a stone tower under construction with scaffolding attatched. It rises in a spiral with workers on the top. There are holes for logs in the tower marking the previous position of the scaffolding.

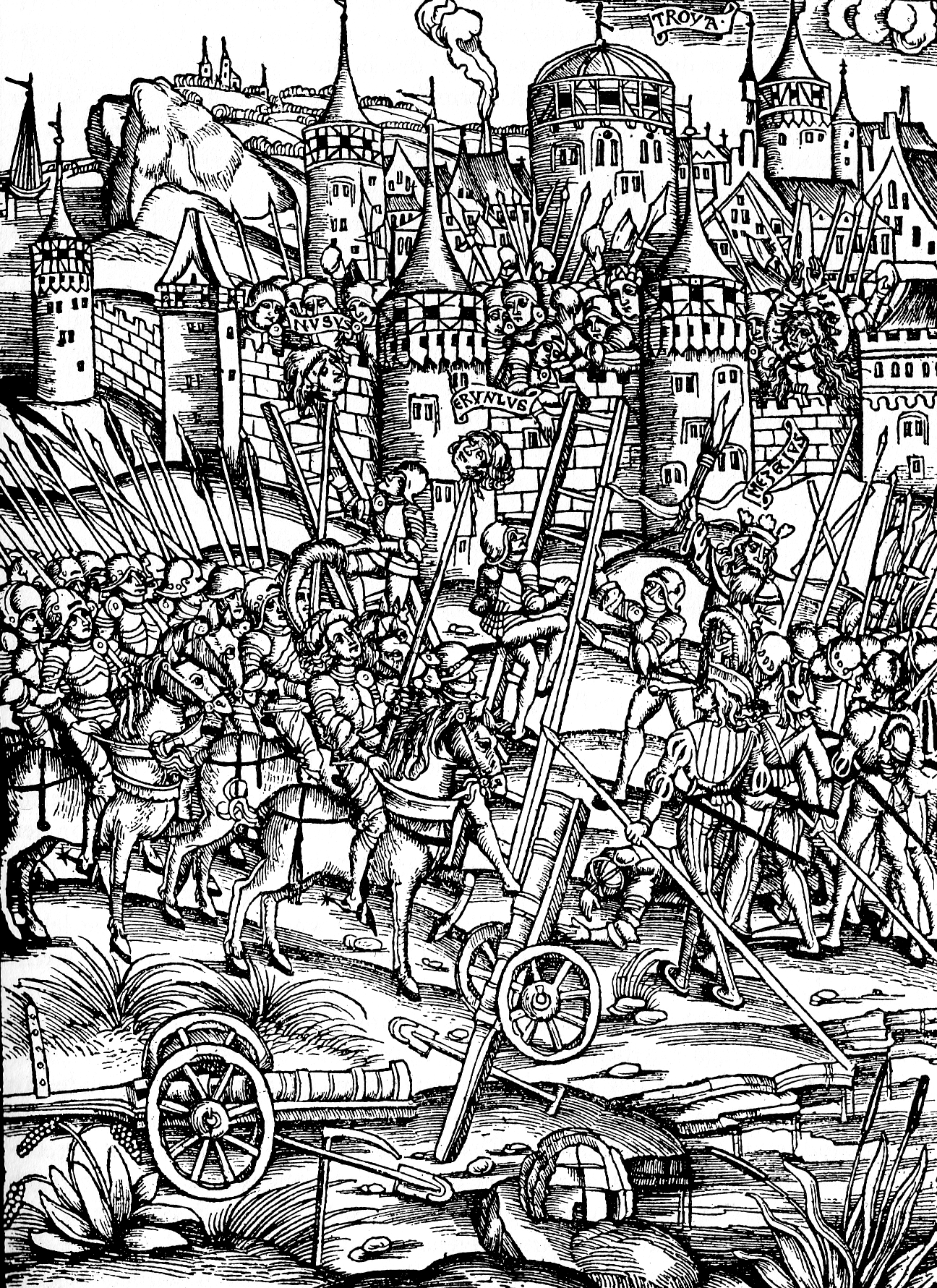

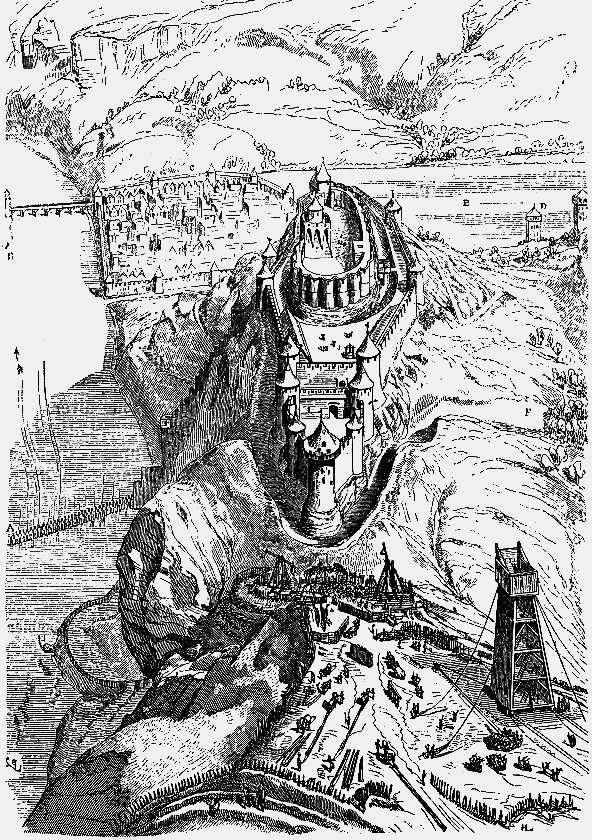

Engraving of the Siege of Troy, but depicting the scene as it would have appeared at Holschnitt, Germany, 1502.

Engraving of the Siege of Magdeburg, Germany 1630-1631.

Siege warfare may have been practiced in Sumer as early as the third millennium BC. Based on ancient reliefs, the Assyrian army that destroyed the Biblical Kingdom of Israel and nearly did the same to Judea, already possessed a considerable array of apparently effective siege engines. They made use of ropes which had been attached to hooks, crowbars, scaling ladders, rams, and siege towers. They constructed mantelets which were basically wagons mounted with armour in front and which could be pushed close to the walls while providing cover for the archers. They also undermined the Hebrew defenses with tunnels and mines.

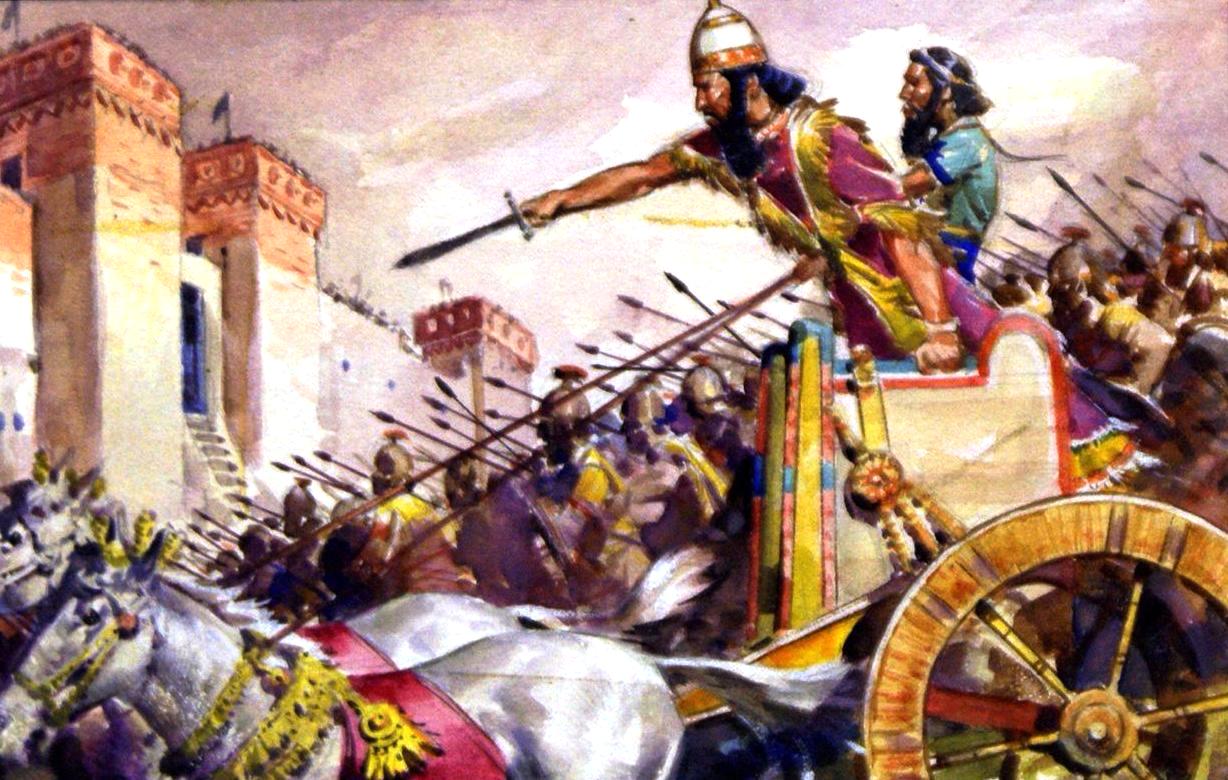

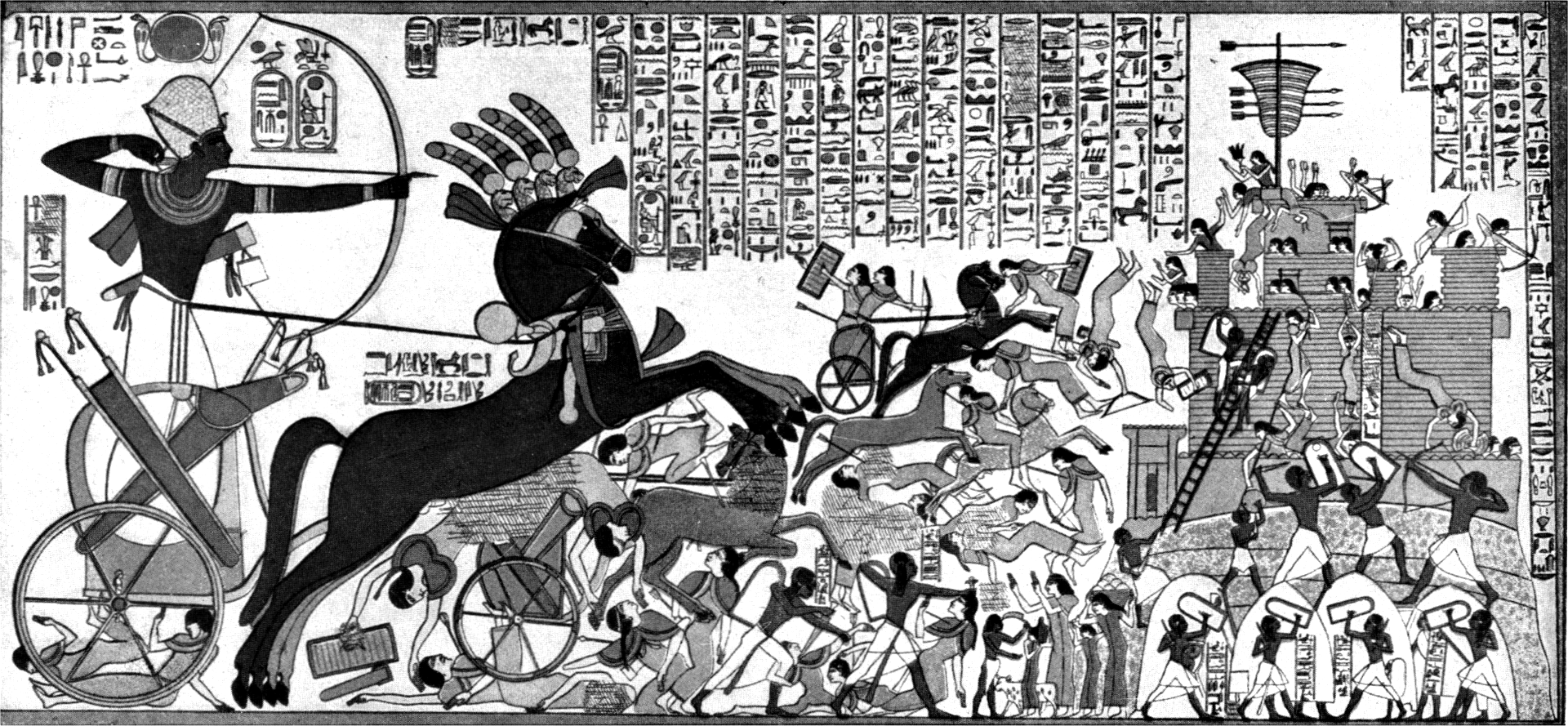

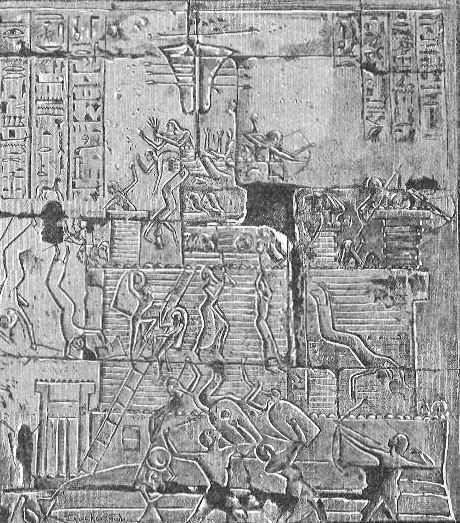

Siege of Dapur, ca. 1269 BC

The Siege of Dapur occurred as part of Ramesses II’s campaign to suppress Galilee and conquer Syria in 1269 BC. He described his campaign on the wall of his mortuary temple, the Ramesseum in Thebes. The inscriptions say that Dapur was “in the land of Hatti”. Although Dapur has often been identified with Tabor in Canaan, it may have been in Syria, to the north of Kadesh. From Egyptian reliefs it appears that Dapur was a heavily fortified city with both inner and outer walls, and situated on a rocky hill which was usual for Syrian cities and many other cities in the Bronze Age. Contemporary illustrations of the siege show the use of ladders and chariots with soldiers climbing scale ladders supported by archers. Six of the sons of Ramesses, still wearing their side locks, also appear on those depictions of the siege. (Kitchen, Kenneth A. Ramesside Inscriptions, Wiley Blackwell, 1998)

(Nordisk familjebok)

Ramesses II and his Egyptian Army engaged in the siege of Dapur, from a mural in Thebes.

The Egyptians of the New Kingdom which began in 1567 BC engaged in sieges using two new weapon’s systems adapted from their temporary conquerors, the Hyksos. The first was a double-convex composite bow made of wood, horn and sinew which was bound or glued together so that when it was unstrung or “at rest,” it appeared to be bent in the reverse direction from which it was designed to fire. When it was strung, drawn and fired, it had a range of 400 yards. Their second development was the single-axle chariot with spoked wheels which provided mobility for their archers and spearmen. When the Egyptians assaulted a fortified city, they hacked at the gates with axes and stormed the walls using scaling ladders. To protect themselves as they did so, they slung their rectangular shields over their backs, which left their hands free for climbing and fighting. Using this method, they successfully stormed and captured the Canaanite city of Megiddo in 1468 BC.[8]

The Egyptian siege of Dapur in the 13th century BC, Bas-relief from the Ramesseum, Thebes.

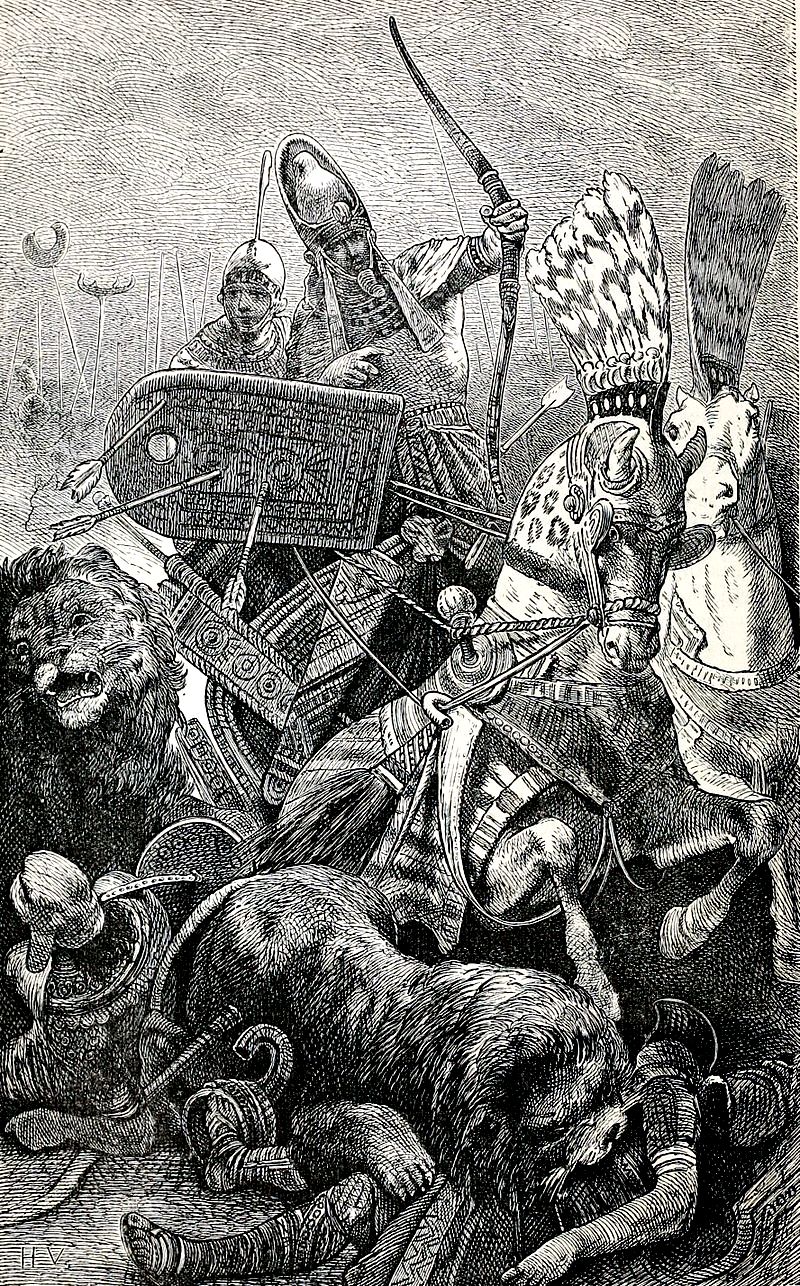

Ramesses II (The great Sesostris), at the Battle of Khadesh, ca 1274 BC, between the forces of the Egyptian Empire under Ramesses II and the Hittite Empire under Muwatalli II at the city of Kadesh on the Orontes River, just upstream of Lake Homs near the present-day Syrian-Lebanese border.

Assyrians using siege ladders in a relief of attack on an enemy town during the reign of Tiglath-Pileser III 720-738 BCE from his palace at Kalhu (Nimrud). (British Museum collection, gypsum relief on loan to the Getty Villa)

Subterfuge was also used. Thutmose III’s General Thot pretended to be abandoning a long siege at Jaffa in Palestine, by offering the defenders 200 baskets or sacks of supplies and tribute. Once they had been brought inside the walls, a soldier emerged from each container. These men then formed up and captured the gates, which allowed the Egyptian army waiting outside to gain access and to seize the rest of the city.[9]

The battering ram was one of the earliest inventions to overcome fortifications, and its use dates from at least 2500 BC. By 2000 BC, it was a normal implement of warfare. The ability to fasten large spear blades to the front end of long wooden beams allowed engineers to pry stones loose from the walls until a breach was achieved. The Hittites used the technique of building an earthen ramp to a low spot in the wall on which they then rolled large, covered battering rams into place to attack the wall at its thinnest points. The Assyrians built wooden siege towers taller than the defender’s walls and then used archers to provide covering fire for the battering ram crews working below. The Assyrians also perfected the use of the scaling ladder by using short ladders to mount soldiers with axes and levers who dislodged the stones in the wall at midpoint. Longer ladders were used to bring combat forces over the higher walls.[10]

Most of the early siege engines were made of wood, often in combination with leather and on occasion wickerwork to provide protective coverings for the attackers. In later years, iron plates were attached to them in order to provide additional armor for the sides of towers and covered siege devices exposed to a defender’s fire. Iron was relatively scarce in medieval times and was used mainly for the heads of battering rams and of course for the nails, rivets, axles, and hinges between moving parts that a good number of these devices required. Virtually all of the medieval siege engines were powered by man or beast.

In the Bible in the book of 2 Chronicles, King Uziah of Judea made use of stone throwing engines to protect Jerusalem:

“Uzziah built towers in Jerusalem at the corner gate, and at the valley gate, and at the turning of the wall, and fortified them. Also he built towers in the desert…(and) had a host of fighting men, that went out to war by bands under the hand of Hananiah, one of the king’s captains…2,600 chiefs (with) 307,500 that made war…And Uziah prepared for them throughout all the host shields, and spears, and helmets, and habergeons, and bows, and slings to cast stones. And he made in Jerusalem engines, invented by cunning men, to be on the towers and upon the bulwarks, to shoot arrows and great stones withal.”[11]

More details on the use of mechanical siege engines will be found in a later chapter. The storage of energy and the use of technology to launch missiles against a determined defender changed the face of war. A new kind of warrior was required in the form of engineers with technical expertise and professionalism. Mathematical calculations in the use of mechanical siege devices became the norm from about 200 BC until the dark ages, when they appear to have been forgotten for a period of time until they re-emerged in the middle ages.[12]

(I, Luc Viatour Photo)

Reconstruction of a Trebuchet at Château de Castelnaud, France.

(Krzysztof Golik Photo)

Château de Castelnaud is a medieval fortress in the commune of Castelnaud-la-Chapelle overlooking the Dordogne River in Périgord, southern France. It was erected to face its rival, the Château de Beynac. The oldest documents mentioning it date to the 13th century, when it figured in the Albigensian Crusade; its Cathar castellan was Bernard de Casnac. Simon de Montfort took the castle and installed a garrison; when it was retaken by Bernard, he hanged them all. During the Hundred Years’ War, the castellans of Castelnaud owed their allegiance to the Plantagenets, the sieurs de Beynac across the river, to the king of France. It eventually fell into ruin, but it has been restored and is a private property open to the public, houses a much-visited museum of medieval warfare, featuring reconstructions of siege engines, Mangonneaux and trebuchets.

(I, Luc Viatour Photo)

Château de Beynac. The castle was built in the 12th century by the barons of Beynacto close the valley. The sheer cliff face being sufficient to discourage any assault from that side, the defences were built up on the plateau: double crenellated walls, double moats, one of which was a deepened natural ravine, double barbican.

(I, Luc Viatour Photo)