German Medieval Castles and Fortresses

(Burgen, Festung und Schlosser)

(Author’s artwork)

My version of Albrecht Durer’s Medieval German Knight with a castle (also known as a Schloss, Berg or Festung).

Oil on canvas, 16 X 20.

My father served with the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) at 3 (F) Wing, Zweibrücken, Germany, (1959-1963), and often took our family castle hunting throughout our time in Europe. This generated a huge interest for me in exploring and examining these historic time capsules. After I joined the Army, I too had the extraordinary privilege of serving with Head Quarters Canadian Forces Europe (HQ CFE) based at CFB Lahr, from 1981 to 1983, and with 4 CMBG also based at CFB Lahr, from 1989 to 1992. I have explored, photographed, painted pictures and documented castles from one end of Europe to the other, and you will find other pages describing some of them on this website. This page is specifically dedicated to medieval castles in Germany, and some of their history as a supplement to the other pages on castles near Zweibrücken, Baden-Soellingen, and Lahr on this web site. I hope you find them interesting.

Canadian Forces Europe (CFE) consisted of two formations in what was known as West Germany before the Berlin Wall fell in November 1990. These formations included Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Lahr with 4 Canadian Mechanized Brigade Group (4 CMBG) (1957-1993), and No. 1 Canadian Air Division (1 CAD), RCAF, at CFB Base Baden-Soellingen and CFB Base Lahr, which later became No. 1 Canadian Air Group (1 CAG). Both formations were closed in 1993 with the end of the Cold War. Many Canadian families took the opportunity to explore and tour the countryside surrounding these communities, and some of these castles may be very familiar to you.

The 12th century castle near Lahr named Hohengeroldseck, and a secondary castle overlooking it, Schloss Lutzelhardt near Seelbach were two that most would have visited. There are many more and the aim of this page is to tell you a bit some of them that stand further afield. Burgruine Hohengeroldseck, Seelbach. The castle, of which the approximately 10 m high outer walls (lower castle) and the main building (upper castle) have been preserved, was built around 1260 as the family seat of the Lords of Geroldseck. After an eventful history, it was destroyed by French soldiers in 1688.

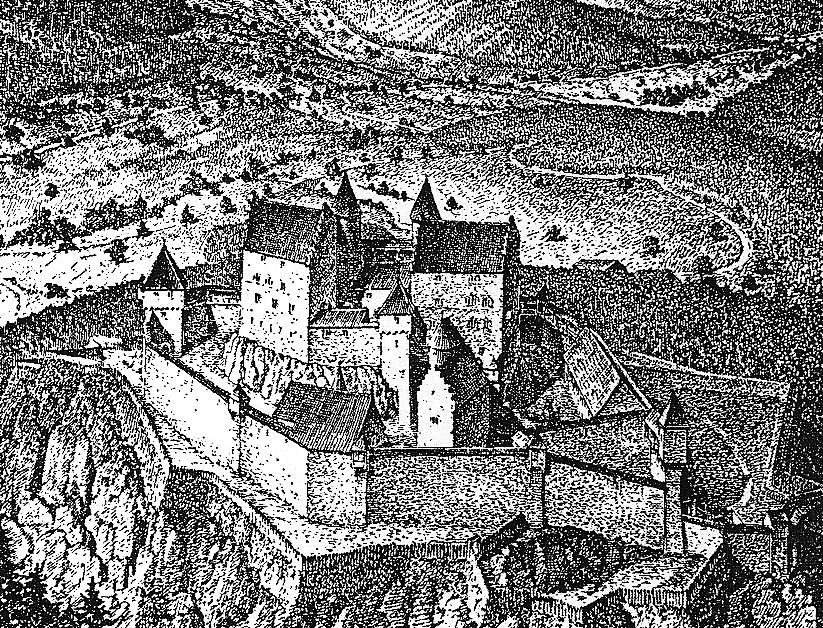

Burg Hohengeroldseck

(Lahr Historical Society Photo)

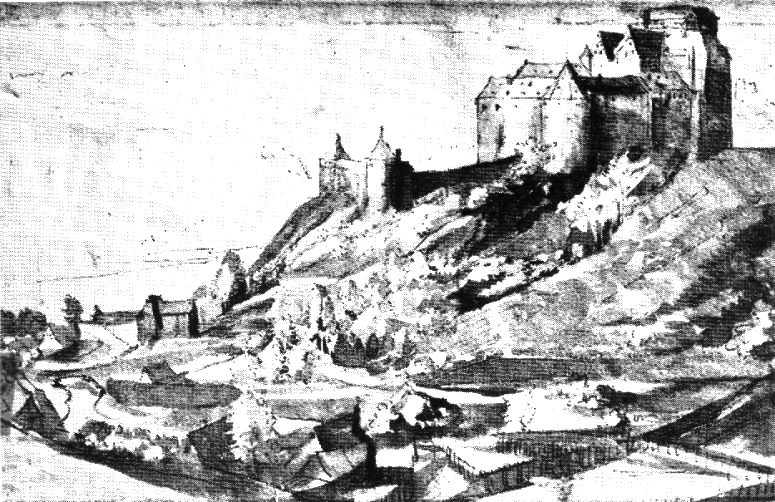

Lahr: Burg Hohengeroldseck, as it appeared before its destruction in the 1689. The castle was built ca 1270 on the Seelbacher Schönberg mountain between Schutter and Kinzigtal in the Ortenau, not far from Offenburg and Lahr. Hohengeroldseck was a state of the Holy Roman Empire, and it served as the family seat of the Lords of Geroldseck, initially under Walther I von Geroldseck.

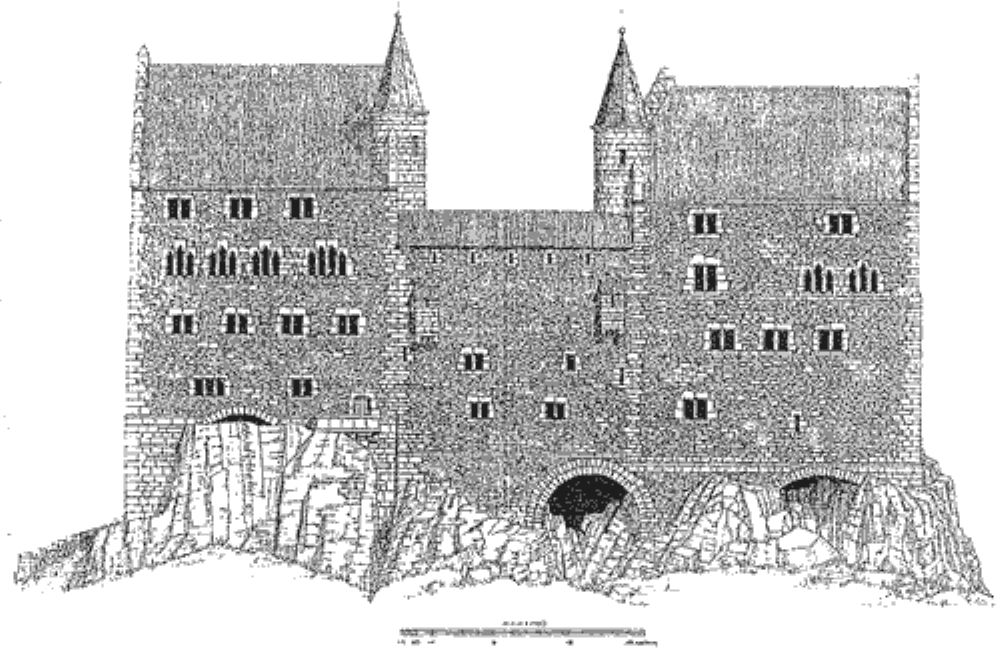

Lahr: Profile of Hohengeroldseck before its destruction.

The Geroldseck family had initially built a small castle, first mentioned in 1139, on the edge of the Gengenbach monastery area (called Rauhkasten, and later Alt-Geroldseck). The family prospered in the 13th century and chose a more suitable location to build a more impressive fortification, c1250/60. c1260, they supported the Bishop of Strasbourg, who shortly afterwards was overthrown by the Strasbourg citizens in a battle in 1262 and died shortly afterwards. Ownership of the castle began to divide in 1277, through inheritances, and again in 1301 and in 1370.

Claims on the castle were made by the Counts of Moers-Saar Werden, resulting in the Geroldsecker War of 1433 in which they were unsuccessful. In 1434 and 1470 the ownership of the castle was further partitioned. c1473/1474, the city of Strasbourg besieged the castle without success. In the power struggle between the Habsburgs and the Electoral Palatinate, the castle was again besieged, captured and occupied until 1504, by Count Palatine Philipp.

The castle was administered by the Margraves of Baden until c1534, when the Geroldsecker family was again permitted to inhabit the castle. When Dautenstein Castle was converted into a Renaissance castle in 1599, the Geroldsecker family moved there. When the Geroldsecker family died out in 1634, the castle came into the

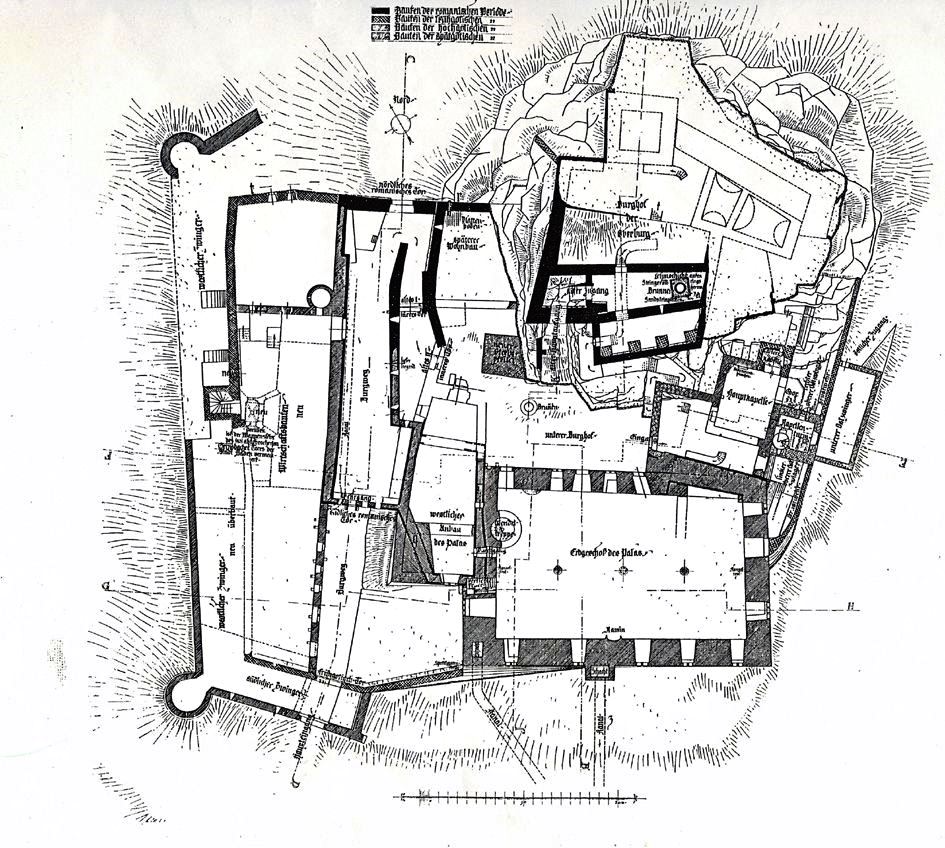

possession of the Counts of Cronberg (Taunus). In the Palatinate War of Succession, the castle was set on fire when the French left in 1689. A planned expansion to the fortress did not take place in the following period, with the exception of a few earthworks. In 1692, the ruins were awarded to the Barons von der Leyen. The earliest contruction work done on Geroldseck Castle took place in the 13th century. The castle was built with two strong residential buildings in the form of a large double palace. Much of the building is Gothic in form, including windows and door walls, dating some of the work to the 14th century. Few of the original 13th centuryworks have survived, and those are mainly in the lower parts of the building. In 1390 the complex was destroyed by lightning. No reliable information is available about the extent of the restoration after the castle was partly destroyed again in 1486. Hohengeroldseck was destroyed for the final time by the French in 1689 and has been in ruins ever since. From 1883 repair work has been carried out on the castle ruins. At the beginning of the 1950s, a new spiral staircase was installed in the tower of the rear hall. Since 1958, the castle has been maintained by an association based in Seelbach.

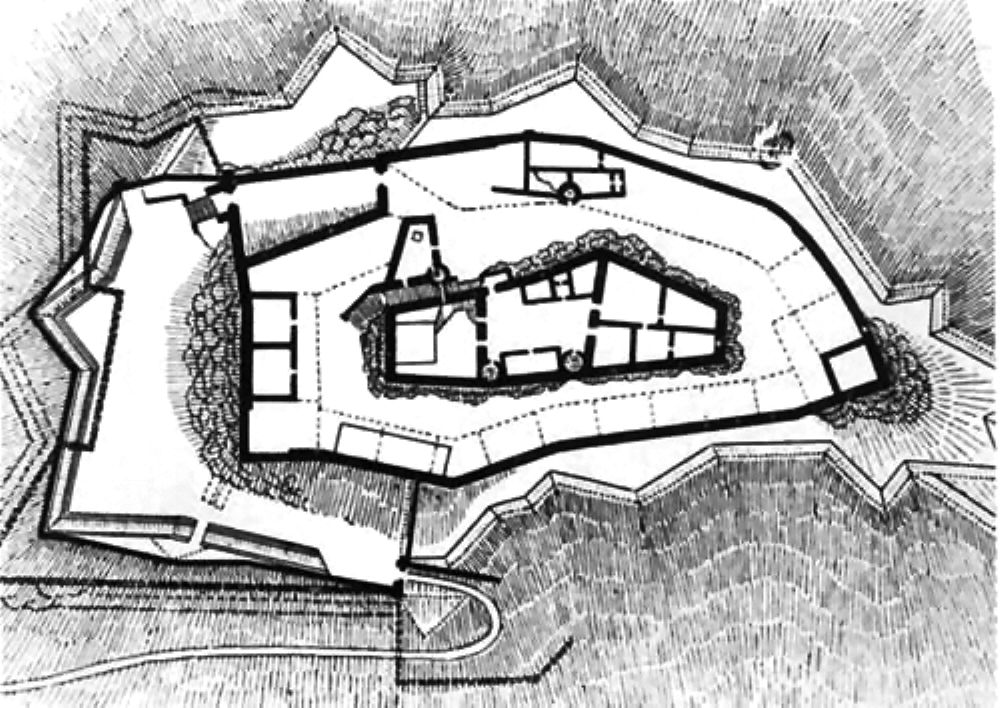

Access to the castle is gained through a Renaissance era or early Baroque gate to a bastion, then through the late medieval (heavily restored) main gate and then by an older gate into the lower courtyard. The lower castle extends as a wide court around the oval core castle, which is raised on a porphyry rock. A defendable well house with its outer walls seems to date from the 14th century. The well shaft is estimated to be 65 m deep, but is partially filled at present. The remains of a building with a stair tower belong to the 16th century, as do the remains of a building in the southeast corner of the lower castle. An older cistern there was vaulted. An exposed, lower-lying forge with a sandstone trough dates from the time before the partial destruction in 1486. There are additional traces of the wall in the ground above the gate chamber.

One of the two palas buildings in the main castle is in good condition, the other is only preserved in sparse, heavily restored remains. Inside, on the high mantle wall between the two palace buildings, there was a low kitchen, flanked by two round stair towers that opened up the palace buildings. In addition to the stair tower, which has been preserved up to the eaves of the stone roof, the well-preserved palace building also shows many structural details such as rectangular windows, pointed arched windows, chimneys, a possible toilet niche and the remains of a stair gable. The main building of the palace is believed to have taken place in the 14th century. The remains of the initial 13th century castle are few, although elements can be seen in the lower masonry.

(Hugo Schneider Map)

Hohengeroldseck Schlossberg, Seelbach, Germany, ground plan.

(Bully’s from Hohengeroldseck Photo)

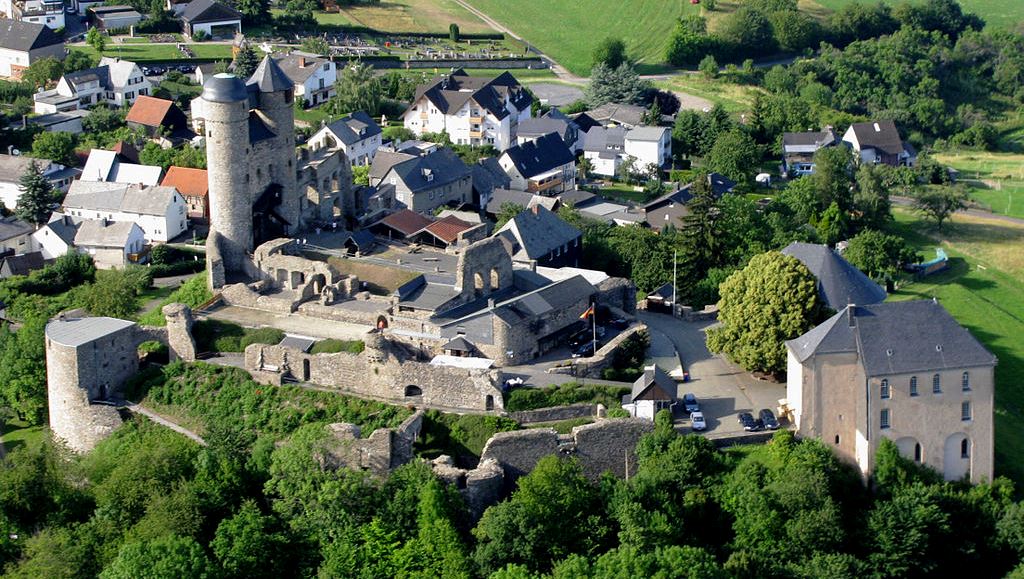

Aerial view of Hohengeroldseck.

For those Canadian families who lived near 4 (F) Wing Baden-Soellingen, No. 1 Canadian Air Division (1 CAD), RCAF, later No. 1 Canadian Air Group (1 CAG), there are many castles close to the what was CFB Baden-Soellingen before it closed in 1993. Burg Hohenbaden would be one of them most would be familiar with.

Burg Hohenbaden

(Muck Photo)

Baden-Baden: Burg Hohenbaden (Alten Schloß Baden-Baden), was the seat of the Margraves of Baden in the Middle Ages. They named themselves after the castle, which gave the state of Baden its name. The castle was built as the first dominion center of the Margraves of Limburg after the relocation of their rule to the Upper Rhine on the western slope of the rocky mountain Battert above what was then called Baden. The construction of the upper castle, the so-called Hermannsbaus, by Margrave Hermann II (1074–1130) is assumed to have started around 1100. From 1112 the Margraves of Baden named themselves after the castle. Under Margrave Bernhard I of Baden (1372–1431) the Gothic lower castle was built, which was expanded by Margrave Jakob I (1431–1453) to become the representative center of the margraviate.

The most important component is the Bernhard Building (around 1400), whose column on the ground floor with a coat of arms carried by angels once supported the mighty vault. In its heyday, the castle had 100 rooms. In the same century, Margrave Christoph I expanded the New Castle, which was begun in 1370, in the city of Baden and moved the residence there in 1479. The old castle then served as a widow’s residence, but in 1599 it was destroyed by fire. The ruins were not structurally secured until after 1830. It was later looked after by the State Palaces and Gardens of Baden-Württemberg.

The old castle has belonged to Wolfgang Scheidtweiler since 2017. From its tower you have a good panoramic view of Baden-Baden and a distant view of the Rhine plain and the Vosges. The castle courtyard of the ruin is also worth seeing. The castle and tower can be visited free of charge. There is a restaurant in the castle. The castle is a popular starting point for hikes on the Battert with its scenic, protected climbing rocks and a protected forest.

A large wind harp stands in the ruins of the great hall of the old castle. The harp, which was set up in 1999, has a total height of 4.10 meters and 120 strings, it was developed and built by the local musician and harp maker Rüdiger Oppermann, who called it the largest wind harp in Europe. The nylon strings are stimulated by the draft to produce the basic notes C and G. From 1851 to 1920 there was a small wind harp in the knight’s hall of the old castle. (Baden-Württemberg I. Die Regierungsbezirke Stuttgart und Karlsruhe. München 1993)

Ground plan of Burg Hohenbaden.

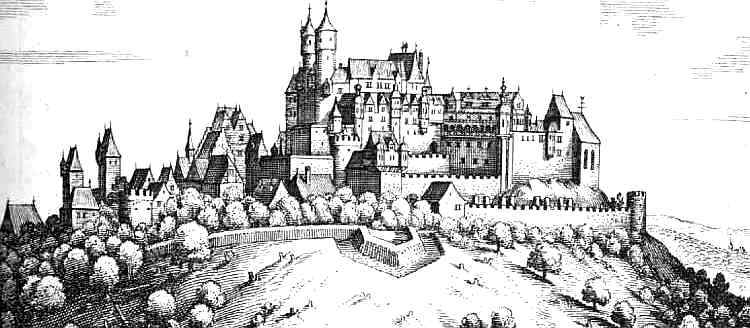

Burg Hohenbaden in the 15th century, illustration by Wolfgan Braun.

(Stadtwiki Photo)

Aerial view of Burg Hohenbaden.

(Martin Dürrschnabel Photo)

Burg Hohenbaden.

(Muck Photo)

Schloss Hohenbaden.

German Medieval Castles

There are more than 25,000 documented castles and palaces (Burgen and Schlosser) in Germany. This page focuses on the medieval castles with a few photos and some of the documentation describing their history and a few pieces of my artwork. More detailed information can be found on Wikipedia. If I missed any that you think should be included, please let me know.

Burg Eltz, near the Mosel River, Germany, Oil on canvas, 18 X 24. (Author’s artwork, from photos taken 8 Oct 1981, 9 July 1982, and May 2008)

(Author Photo, May 2008)

Burg Eltz, near the Mosel River Germany. Of more than 500 castles in the Rhineland Palatinate region this is one of only three to have survived the many wars and destruction in the region mostly intact since the 11th century. The Eltz family occupied the castle in the 12th century, and then continued to make renovations and additions for centuries afterwards. For this reason it wasn’t fully completed until between 1490 and 1540. The 80-room castle is still occupied today, and looks much as it would have hundreds of years ago. The castle is one of the few in the area that survived the Thirty Years’ War. The French did not destroy the castle thanks to its location, and some skilled diplomacy on the part of the landowners. It is a good walk to get to, up and down a number of hills and forest tracks through a beautiful area and a breathtaking view of the castle. Burg Eltz is one of the hundreds of castles examined by the author while researching material for the book “Siegecraft”. Burg Eltz is, in this author’s opinion, the most interesting of them all.

(Francisco Conde Sánchez Photo)

Eltz Castle (Burg Eltz) is a medieval castle nestled in the hills above the Moselle River between Koblenz and Trier. It is still owned by a branch of the same family (the Eltz family) that lived there in the 12th century, 33 generations ago. Bürresheim Castle, Eltz Castle and Lissingen Castle are the only castles on the left bank of the Rhine in Rhineland-Palatinate which have never been destroyed.

The castle is surrounded on three sides by the Elzbach River, a tributary on the north side of the Moselle. It stands on a 70-metre (230 ft) rock spur, on an important Roman trade route between rich farmlands and their markets. The Eltz Forest has been declared a nature reserve by Flora-Fauna-Habitat and Natura 2000. The castle is a so-called Ganerbenburg, a castle belonging to community of joint heirs. This is a castle divided into several parts, which belong to different families or different branches of a family; this usually occurs when multiple owners of one or more territories jointly build a castle to house themselves. Only wealthy medieval European lords could afford to build castles or equivalent structures on their lands; many of them only owned one village, or even only part of a village. This was an insufficient base to afford castles. Such lords usually lived in “knight’s houses”, which were fairly simple houses, scarcely bigger than those of their tenants. In some parts of the Holy Romain Empire of the German Nation, inheritance law required that the estate be divided among all successors. These successors, each of whose individual inheritance was too small to build a castle of his own, could build a castle together, where each owned one separate part for housing and all of them together shared the defensive fortification. In the case of Eltz, the family comprised three branches and the existing castle was enhanced with three separate complexes of buildings.

The main part of the castle consists of the family portions. At up to eight stories, these eight towers reach heights of between 30 and 40 metres (98 and 131 ft). They are fortified with strong exterior walls; to the yard they present a partial framework. About 100 members of the owners’ families lived in the over 100 rooms of the castle. A village once existed below the castle, on its southside, which housed servants, craftsman, and their families supporting the castle. Platteltz, a Romanesque keep, is the oldest part of the castle, having begun in the 9th century as a simple manor with an earthen palisade. By 1157 the fortress was an important part of the empire under Frederick Barbaross, standing astride the trade route from the Moselle Valley and the Eifel region. In the years 1331–1336, there occurred the only serious military conflicts that the castle experienced. During the Eltz Feud, the lords of Eltzer, together with other free imperial knights, opposed the territorial policy of the Archbishop and Elector Balduin von Trier. The Eltz Castle was put under siege and possible capture and was bombarded with catapults by the Archbishop of the Diocese of Trier. A small siege castle, Trutzeltz Castle, was built on a rocky outcrop on the hillside above the castle, which can still be seen today as a few ruined walls outside of the northern side of the castle. The siege lasted for two years, but ended only when the free imperial knights had given up their imperial freedom. Balduin reinstated Johann again to the burgrave, but only as his subjects and no longer as a free knight.

In 1472 the Rübenach house, built in the Late Gothic style, was completed. Remarkable are the Rübenach Lower Hall, a living room, and the Rübenach bedchamber with its opulently decorated walls. Started in 1470 by Philipp zu Eltz, the 10-story Greater Rodendorf House takes its name from the family’s land holding in Lorraine. The oldest part is the flag hall with its late Gothic vaulted ceiling, which was probably originally a chapel. Construction was completed around 1520. The (so-called) Little Rodendorf house was finished in 1540, also in Late Gothic style. It contains the vaulted “banner-room”. The Kempenich house replaced the original hall in 1615. Every room of this part of the castle could be heated; in contrast, other castles might only have one or two heated rooms.

In the Palatinate War of Succession from 1688 to 1689, most of the early Rhenish castles were destroyed. Since Hans Anton was a senior officer in the French army to Eltz Üttingen, he was able to protect the castle Eltz from destruction. Count Hugo Philipp zu Eltz was thought to have fled during the French rule on the Rhine from 1794 to 1815. The French confiscated his possessions on the Rhine and nearby Trier which included Eltz castle, as well as the associated goods which were held at the French headquarters in Koblenz. In 1797, when Count Hugo Philipp later turned out to have remained hidden in Mainz, he came back to the reclaim of his lands, goods and wealth. In 1815 he became the sole owner of the castle through the purchase of the Rübenacher house and the landed property of the barons of Eltz-Rübenach.

In the 19th century, Count Karl zu Eltz was committed to the restoration of his castle. In the period between 1845 and 1888, 184,000 marks (about 15 million euros in 2015) was invested into the extensive construction work, very carefully preserving the existing architecture. Extensive security and restoration work took place between the years 2009 to 2012. Among other things, the vault of flags hall was secured after it was at risk of partially collapsing walls and the porch of the Kempenich section. In addition to these static repairs, almost all the slate roofs were replaced. Structural problems were remedied in the ceiling and wood damage was repaired. In the interior, heating and sanitary facilities, windows and fire alarm system were renewed, and also historic plaster was restored. The half-timbered facades and a spiral staircase were renovated at the costs of around €4.4 million.

The measures were supported by a €2 million grant from an economic stimulus package provided by the German federal government. The state of Rhineland-Palatinate, the German Foundation for Monument Protection and the owners provided further funds. The Rübenach and Rodendorf families’ homes in the castle are open to the public, while the Kempenich branch of the family uses the other third of the castle. The public is admitted seasonally, from April to October. Visitors can view the treasury, with gold, silver and porcelain artifacts and the armory of weapons and suits of armour.

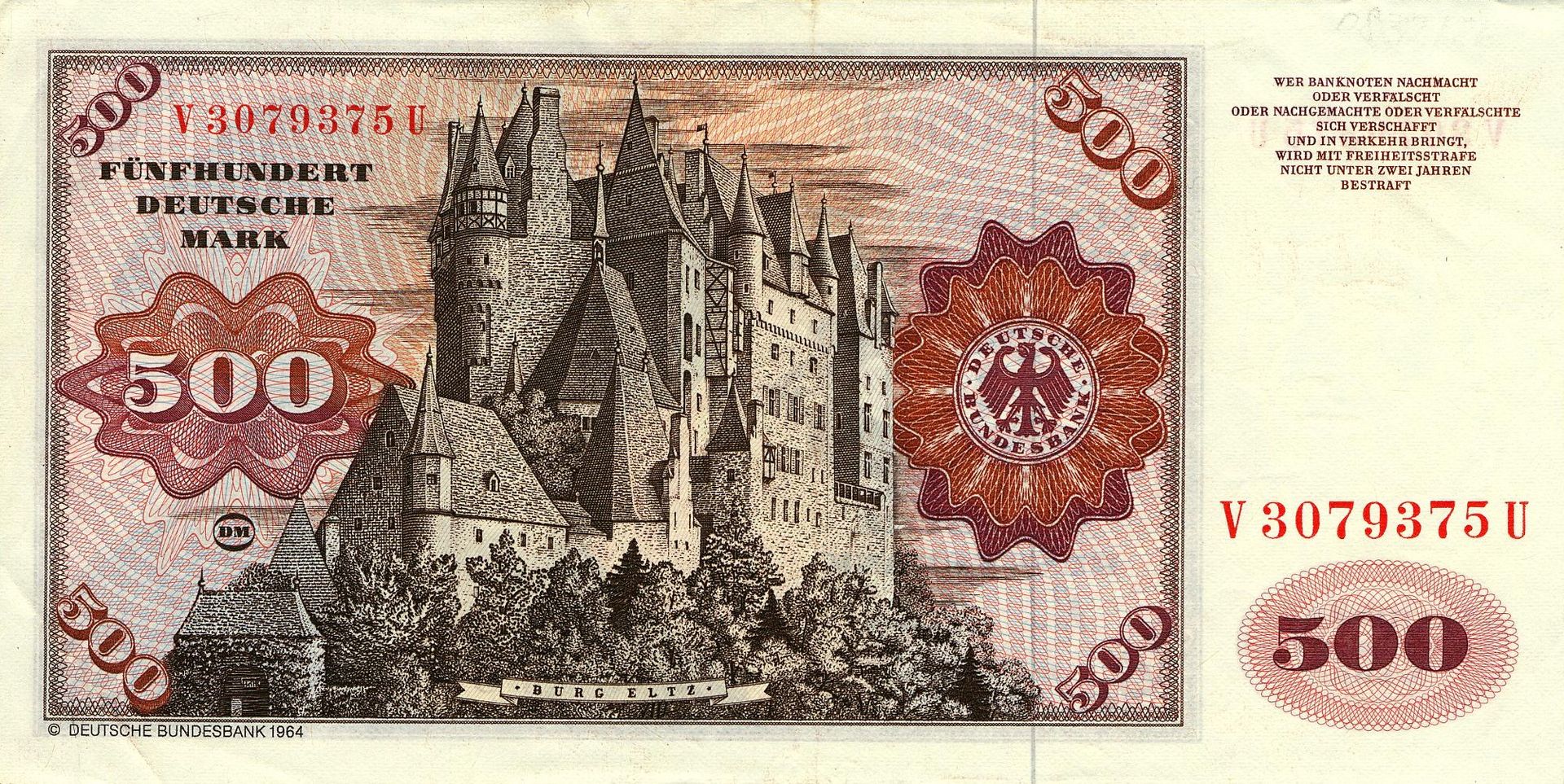

From 1965 to 1992, an engraving of Eltz Castle was used on the German 500 Deutsche Mark note. (de Fabianis, Valeria, ed. (2013). Castles of the World. New York: Metro Books)

(Johannes Dörrstock Photo)

Burg Eltz, morning view.

(Author Photo)

Burg Eltz.

Schloss Bürresheim

(Blueduck4711 Photo, 17 July 2010)

Mayen: Schloss Bürresheim is a medieval northwest of Mayen, Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany. It is built on rock in the Eifel mountains above the Nette. Bürresheim Castle, Eltz Castle and Lissingen Castle are the only castles on the left bank of the Rhine in Rhineland-Palatinate which have never been destroyed. It was inhabited until 1921 and is now a museum operated by the General Directorate for Cultural Heritage, Rhineland-Palatinate.

(Vincent van Zeijst Photo)

Schloss Bürresheim.

(Wolfenkratzer Photo)

Schloss Bürresheim, aerial view.

Burg Altena

(Asio otus Photo)

Burg Altena is a medieval hill castle in the town of Altena in North Rhine-Westphalia. Built on a spur of Klusenberg hill, the castle lies near the Lenne in the Märkischer Kreis. The castle was built early in the 12th century by the Counts of Berg. They eventually abandoned Altena and moved their residence to Hamm.

The castle may have been built by the brothers Adolf and Everhard von Berg around the year 1108 after Henry V granted them land in the Sauerland for their loyal services. They built their castle on Wulfseck Mountain, naming it Wulfeshagen, later Altena. This is one of the several legends of the establishment of the county of Altena and the building of the castle.

After the acquisition of the parish land of Mark near the city of Hamm in 1198, the counts of Altena took Mark Castle as their primary residence and called themselves the Counts of the Mark. They only occasionally inhabited Altena Castle, and from 1392 onward it was only used as a residence for the county bailiff (Amtmann). Count Engelbert III of the Mark gave the small settlement at the base of the mountain the rights of liberty (such as self-governance). In 1455 the castle burned down and was only re-erected partially.

In the Brandenburg-Prussian era, the castle became a garrison until it was sold to the town of Altena in 1771. In the following years an almshouse and a workhouse was established there. This existed until 1840. From 1766 to 1811 there existed a criminal court and prison in the castle. By 1834 the castle had greatly deteriorated and needed to be rebuilt. Due to lack of funds, however, this was not carried out. The Johanniter Order set up a hospital in the buildings.

Due to the 300 year-anniversary of the membership of the County of Mark to Brandenburg-Prussia in 1909 plans for a reconstruction of the castle began. In 1914 this was completed, apart from the outer bailey and lower gatehouse. There was a controversial debate about the modes of reconstruction, where the preference of historic designs over the medieval and early modern architecture was criticised. In 1918 the last works were completed.

In 1914, Richard Schirrmann established the world’s first youth hostel within the castle, which is still in use today (Jugendherberge Burg Altena). The original rooms are a museum today. The youth hostel continues to run at a location on the lower castle court yard, opened in 1934. Today the castle is symbol of the town of Altena and a tourist attraction. The entry ticket is also valid for the nearby Deutsche Drahtmuseum (German Wire Museum). During the first weekend of August a yearly Medieval Festival takes place in the castle and town. Part of the castle is used as a restaurant. (Ernst Dossmann: Auf den Spuren der Grafen von der Mark. 3. Auflage. Mönning, Iserlohn 1992)

(Dr. Gregor Schmitz Photo)

Burg Altena, aerial view.

(Frank Vincentz Photo)

Burg Altena. view from Lüdenscheider Straße.

(Asio otus Photo)

Burg Altena. view from Bismarckstrasse.

Burg Balduinseck

(Crossbill Photo)

Burg Balduinseck (Baldeneck) is a ruined hilltop castle in Hunsrück. It stands 300 m above sea level on a hill about 20 meters above the confluence of the Wohnrother Back and the Schumbach to the Mörsdorger in the district of Buch in the Rhine-Hunsrück district in Rhineland-Palatinate. Archbishop Baldwin of Trier acquired the site in 1325 after a truce arranged with Ritter Richard and Ritter Wirich, leading to the right to build a castle on it. The castle was built in spite of a number of interruptions, in 1331. Its purpose was primarily to counted Kastellaun Castle in the county of Sponheim. Its construction appears to have taken inspiration from Western models, particularly the French donjon style.

The castle was built on a narrow rock spur, and served as the official seat of the Trier administrative district of the same name. When the seat was moved to Zell in the 16th century, the castle became largely insignificant. Owners and administrators often changed, because Balduinseck always remained part of the Trier electoral state. In 1675 the office building was leased. In 1711 the castle fell into neglect and in 1780 it was declared dilapidated. It does not appear to have suffered damage from any of the numerous wars.

The castle ruin is about 55 meters long and up to 20 meters wide in an east-west direction. The outer walls of the 18-meter-high, four-story residential tower are well preserved and give the ruin its distinctive appearance. The residential tower has a footprint of 22.7 × 14.4 meters, the walls are up to 2.5 meters thick. A spiral staircase on the left side of the main entrance and nine chimneys are preserved, extending over three floors. The fourth floor has no chimneys and was therefore probably used as a storage room and for military purposes. In front of the large main chimney on the ground floor, which is let into the east wall, the remains of a fountain are still present. In addition to the chimneys, the openings for wall cupboards as well as the white interior plaster and a white stripe of the former exterior plaster between the third and fourth floors have been preserved.

After a fire in 1425, the interior of the residential tower was redesigned. Most of the open fireplaces have been converted into closed, smoke-free tiled stoves in favor of more effective heating. The upper floors remained unheated and were only used as storage rooms.

The specialty of the castle is the location of the residential building that was completed first. Contrary to the usual structure of a castle, the residential tower, which was equipped with a defensive core on the east side, stands behind the neck ditch, directly on the attack side. Such an arrangement can be found in other castles built by Baldwin of Luxembourg.

In front of the residential tower are the remains of a subsequently erected round tower in the west and the circular wall that was finally built, where a round shell tower open to the castle courtyard is structurally integrated into the south side of the masonry. In addition, the old driveway with neck ditch and the associated bridgehead can still be seen. To the east there are the remains of a second trench with the foundation walls of an advanced tower.

Parts of the foundation were so badly damaged that they could no longer withstand the pressure of the masonry. Cracks proved that the entire structure was weakening. It was considered to be in acute danger of collapsing. Therefore, the ruin was subjected to comprehensive security building measures from summer 2009. The work was divided into five construction phases and was completed in 2014. (Alexander Thon, Stefan Ulrich u. Achim Wendt: “… where a mighty tower defiantly looks down”. Castles in the Hunsrück and on the Nahe, Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2013)

(Rabax63 Photo)

Burg Balduinseck. Main entrance to the tower house on the west side; to the right is the entrance to the spiral staircase

(Rabax63 Photo)

Burg Balduinseck.

Burg Lissingen

(Frank Martini Photo)

Lissingen: Burg Lissingen is a well-preserved former moated castle dating to the 13th century. It is located on the River Kyll in Gerolstein in the administrative district of Vulkaneifel in Rhineland-Palatinate. From the outside it appears to be a single unit, but it is a double castle; an estate division in 1559 created the so-called lower castle and upper castle, which continue to have separate owners. Together with Bürresheim and Eltz, it has the distinction among castles in the Eifel of never having been destroyed. Lissingen Castle is a protected cultural property under the Hague Convention.

The castle is located on the edge of Lissingen, a district of the city of Gerolstein, close to the river Kyll. It was originally surrounded by the river and on the south and west sides by a moat. The moat has been filled in and streets created on the site, but traces of the original water defenses are visible on the river side of the castle. Lissingen and neighboring Sarresdorph most likely originated as a Roman settlement. Evidence of this is based on archeological finds from an excavation in one of the courtyards of the lower castle before the First World War, and also by its proximity to the former Roman settlement of Ausava, a horse-changing station on the road between Treves and Cologne that today is the section of Gerolstein called Oos.

After the Germanic influx of the 5th century, the former Roman settlements came under the control of the Frankish kings and later became demesne of the Merovingians and Carolingians. In the 8th and 9th centuries, during the Carolingian era, Lissingen and Sarresdorph were both possessions of Prüm Abbey or of its estate of Büdesheim. Following attacks on the abbey by Normans in the 9th century, fortified towers and later castles were built to protect it. The castle at Lissingen took its present form as a defensible complex of buildings during the heyday of chivalry in the High Middle Ages. The first documentary mention of Lissingen Castle dates to 1212, as a possession of the Ritter (knight) von Liezingen. In 1514, Prüm Abbey enfeoffed Gerlach Zandt von Merl with Lissingen. In 1559, the castle was then divided into two sections, the upper and the lower castle.

In 1661–63, Ferdinand Zandt von Merl almost completely rebuilt the lower castle. By incorporating three medieval residential towers, he created an imposing manorial residence. There was a small annexed chapel, which is mentioned in 1711 and 1745 as the oratory of the von Zandt family. This was surrendered in the early 20th century. After Anton Heinrich von Zandt’s death in 1697, Wilhelm Edmund von Ahr was the owner of the castle. He doubled the size of the inhabited part of the castle. In 1762, the elector of Trier (as procurator of Prüm Abbey) enfeoffed Josef Franz von Zandt zu Merl with Lissingen. A few years later, in 1780, as an Imperial Knight of the Holy Roman Empire, the latter became Freiherr of Lissingen, a small autonomous territory. Lissingen retained this status until the abolition of the Feudal system, and the castle was greatly extended, in particular by the addition of a much larger tithe barn and stables.

As a result of the French Revolutioin, in 1794 the region of the left bank of the Rhine, including the estate of Lissingen Castle, came under French administration. The Eifel became a Prussian possession in 1815. In the years that followed, both sections of the castle changed hands several times, until they were reunited in 1913 under a single owner, who developed the property into a large agricultural operation. The construction of a small power plant, which began operation in 1906, had an appreciable effect on the economic operation of the castle. This provided electricity for the castle, approximately 50 houses in the settlement of Lissingen, and the local train station. Private power generation ended in 1936, when the Rheinisch-Westfälisches Elektrizitätswerk took over service to Lissingen.

In 1932, a Cologne brewery owner by the name of Greven acquired the property, which had been affected by the international economic crisis. He developed the large agricultural infrastructure on the south side of the castle, including in 1936 a new cowshed with a milking parlor, a milk processing plant, a refrigerated storage area and one of the first milk bottling plants in the Eifel. During the Second World War, the castle served as a billet for several Wehrmacht regiments and as command post for the German General Staff. Towards the end of the war, it was used as a temporary prison for highly ranked military captives.

After the war, the Greven family resumed dairy and livestock farming operations. Until 1977, the lower castle was operated as an agricultural enterprise by a leaseholder. However, the estate ceased to be economically viable as a farm. The castle buildings, especially the gatehouse of the upper castle and the entire lower castle, were increasingly neglected and fell into disrepair. Investment in the buildings resumed only after both sections of the castle came into the hands of new owners.

In 1987 the lower castle was acquired by Karl Grommes, a patent attorney from Koblentz. He has carried out wide-ranging restoration work and added furniture, household effects, and workshops, with the intention of restoring the appearance of the entire ensemble to provide insights into life and work in such a castle and on its grounds. As of 2011, the following parts of the castle are open to visitors: the picturesque old courtyard of the lower castle, the main house with cellar, kitchen, and living spaces, the tithe barn and other outbuildings, and the estate, with numerous relics of the past. There are permanent exhibits on sleighs, carriages, church weathervanes, and historical building materials. After five years as a traveling exhibition, the Eifel Museums special exhibition Essens-Zeiten (Mealtimes) has been permanently housed at the castle. In addition, the lower castle is available for gastronomic and cultural events, such as marriages, conferences, art projects, and exhibitions. It has a bakery with a historical brick oven, a restaurant, and a civil registry office.

The upper castle was acquired by Christine and Christian Engels in 2000. It is a private residence but can be visited by appointment. As of 2011 some rooms are available as vacation rentals. The whole castle complex is divided into two parts: firstly, the lower castle, which includes various buildings, courtyards, open areas, and also the attached land or meadow; and secondly, the upper castle, which also includes buildings, a courtyard, and open areas. Today the palatial manor house is in Renaissance style. It was created in 1661–63 by combining three medieval residential towers into a single angled structure. The oldest architectural remnants in the castle are to be found in the cellar of this building and in the vaults under the large terrace in front of it, and may date to the Carolingian era. On the ground floor, in addition to reception and dining rooms, there is a rustic estate kitchen. Above this floor is a mezzanine level with appreciably lower ceilings, which formerly housed the actual living spaces for the owners. The upper floor above that contains three high-ceilinged formal rooms with remarkable sandstone chimneypieces.

The castle mill was originally a freestanding building outside the castle defenses. It was integrated into the castle complex only in the course of later extensions that resulted from the division of the castle. The mill ground wheat for flour; the miller paid 5 malter of grain, 6 guilders and 8 albus in rent and for water usage. In addition, the lords of the castle were permitted to have their grains ground free at any time with no flour kept back by the miller.

By the early 20th century, electricity was being generated at the mill using the water; this was the origin of the later power plant. Around 1920, a large wood-fired stone oven, a so-called Königswinter oven, was installed, which provided the bread needed by the many people living and working at the castle. The oven has been restored and is again in use, providing baked goods for purchase and for consumption at the castle.

On the western side of the castle there is still a large meadow area, bordered in part by the Oosbach stream and in part by a millstream that branches off from it. The Oosbach originally fed the moats and later provided water to drive the mill and the electrical generator. In addition the water was used for the animals, to farm fish, and for firefighting. The millstream has largely been preserved and it has been possible to briefly reactivate it. The meadow area has been restored to showcase various biota and sculptures and provide locations for relaxation and nature observation. In 2004 it was featured in the Trier garden show. The lower castle grounds also include the historic approach to the castle (the Im Hofpesch path and the millrace path, both with old trees along them) and the upper stretch of the millstream and the sluice that diverts the water from the Oosbach. (Peter Bartlick. Geschichte der Burg Lissingen. Gerolstein, 2010)

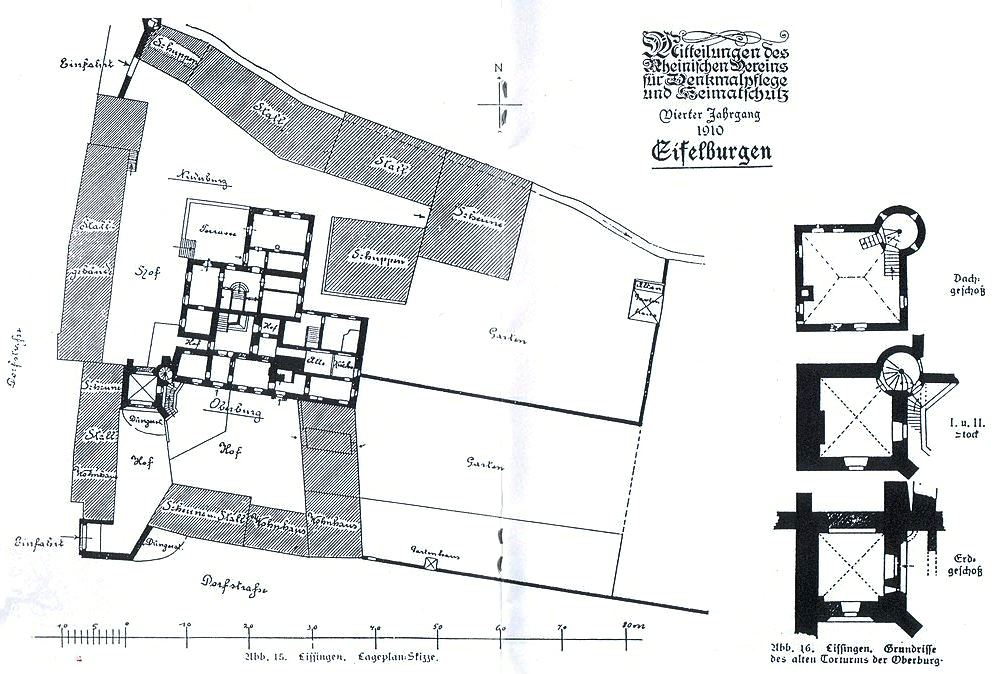

Ground Plan of Burg Lissingen.

(Wolfenkratzer Photo)

Aerial view of Burg Lissingen.

Burg Breuberg

(Haselburg-müller Phoro)

Burg Breuberg, also called Kernburg (core castle) was probably founded around or shortly after 1200 by the imperial abbey of Fulda under Abbot Markwald I, to secure Fulden properties in the Odenwald. It is one of Germany’s best preserved castles. c1200 the bailiwick was taken over by the Lords of Lützelbach, who then called themselves Lords (Herren von) of Breuberg. Only the keep and the late Romanesque portal of the main castle can be dated to the earliest construction phase of the castle. Residential buildings from this time have not survived, although individual walls from earlier buildings could be built in the buildings of the core castle.

In 1323, the male family line of the house of Breuberg died out with Eberhard III of Breuberg. From the 14th century, the castle was expanded many times, making it today a journey through the building styles of the last 850 years. Half of the property went to Konrad von Trimberg, a quarter each to the Counts of Wertheim and the Lords of Weinsberg. The fragmentation of the property becomes clear in the complicated ownership structure of the following time: In 1336 three quarters of the castle belonged to Wertheim, Trimberg and the Lords of Eppstein each held an eighth. In 1337 a partition agreement was signed in which it was recorded which party belonged to which parts of the castle and who had to maintain them. Essential parts like the well were maintained jointly.

In 1446, Count Wilhelm of Wertheim sold Count Philipp the Elder of Katzenelnbogen his share of the castle for 2400 Gulden. The castle played an important role in territorial policy from Wertheim’s side, which is why the counts endeavored to gradually acquire it in full. But it was not until 1497 under Count Michael II that this succeeded with the purchase of the last stake. A little more than 50 years, between 1497 and 1556, the Counts of Wertheim owned the castle completely. Many construction measures took place during this time, especially the adaptation for the use firearms with the construction of the gun turrets and the cannon platform (Schütt). New buildings were erected in the castle, such as the Wertheim armory (1528) and parts of the gateway . Breuberg thus became a small Wertheim residence, but also a fortress against the ambitions of larger sovereigns such as the Landgraves of Hesse, the Archbishops of Mainz or the Electoral Palatinate. The town of Neustadt was founded as a settlement below the castle as early as 1378.

After the Count of Wertheim died out in 1556, the castle was divided again. It was then half owned by the Counts of Erbach (from 1747 on the Erbach-Schönberg line ) and the Counts of Stolberg-Königstein. At the beginning of the 17th century, the stolberg-Königstein part of the castle fell to the Counts of Löwenstein-Wertheim (later Löwenstein-Wertheim-Rosenberg ).

During the Thirty Years’ War, Breuberg Castle changed hands several times. Half of the fortress belonged to sovereigns with different loyalties. With the advance of Gustaf to Franconia, the Protestant Counts of Erbach took over the castle completely. The Swedes used Count Gottfried von Erbach as commandant, who damaged the opposing party so much that the County of Erbach later had to pay high compensation. He died in 1635, and was buried in the castle chapel, where his sarcophagus was rediscovered in the 19th century. In the course of the advance of the imperial army after the Battle of Nördlingen, ownership changed back to the Löwensteiners with Count Ferdinand Carl von Löwenstein as commander. In 1637, the Swedes under Jakob von Ramsay, governor of the Hanau Fortress, tried to besiege the castle but were unsuccessful. The Schwedenschanze north of Wolferhof is a reminder of the event. In 1639 the Erbachische Rat, Dr. Backyards was shot by a Löwenstein mercenary as he waited outside the gate to be admitted. In 1644 the Counts of Erbach were able to recapture Breuberg in a surprise attack and kept it occupied until the Peace of Westphalia.

In the larger armed conflicts of modern times, such as the Palatinate and Austrian War of Succession, the fortress was still secured by troops. However, the castle quickly lost its importance as the seat of power. It was used as an administrative and official seat, which was only moved to Neustadt in the first half of the 19th century. Before that, the castle served briefly from the Napoleonic period and belonged to the Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt from 1810 to around 1850. It served as the seat of the Breuberg district, the predecessor of the Neustadt district. After that, a toy factory was housed in the castle at the end of the 19th century. A manufacturer from Mainz had African animals made from wood there. Since he had a brother in the USA, these were shipped and sold in New York in the USA. This ended with the First World War. The castle stood empty for a short time, but remained in the possession of the Erbach (later Erbach-Schönberg, Protestant) and Löwenstein-Wertheim (later the Löwenstein-Wertheim-Rosenberg line, Catholic).

In 1919, the German Youth Hostel Association, which had belonged to the Hitler Youth from 1940 , acquired the castle, making it the property of the German Reich. During the Second World War, slave laborers were housed there, commemorated by a plaque at the entrance gate and incisions in Cyrillic script on the keep. 1946, Breuberg Castle became the property of the newly founded State of Hesse by order of the military government. The castle continues to serve as a youth hostel, and was renovated in 1987.

The oldest part of the castle complex is the main castle on a pentagonal floor plan with remains of the moat and the curtain wall, the cuboid keep and the columned portal at the gate of the main castle. The ring wall the inner castle with characteristic small cuboids should also belong to the earliest times. With 1900 m², the core castle is unusual for the 13th century. The mean value for this time is around 1000 m². The later buildings from the 15th to 17th centuries were placed on top of the older wall. Because no battlements were bricked up, it was concluded that the curtain wall had none. (Elmar Brohl: Fortresses in Hessen. Published by the German Society for Fortress Research eV, Wesel, Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 2013)

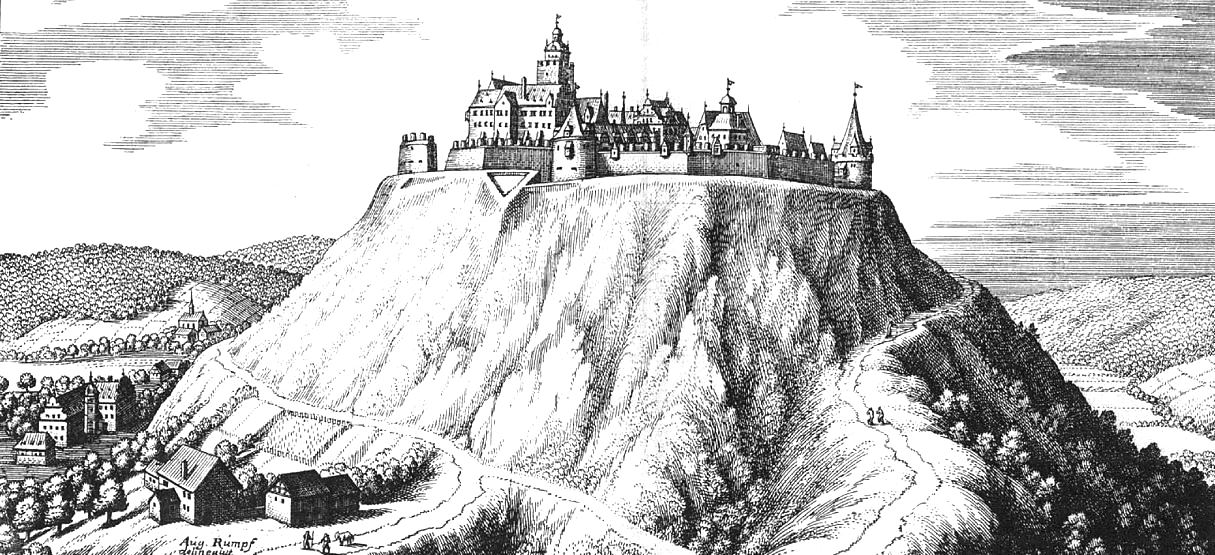

The high house of Breuberg. Merian engraving from Topographia Franconiae 1648.

(Tomgoebel Photo)

Burg Breuburg. Entrance to the outer bailey and gateway.

Hardenburg

(BlueBreezeWiki Photo)

Bad Dürkheim: Hardenburg stands on the eastern edge of the Palatinate Forest near the Rhineland-Palatinate town of Bad Dürkheim. It is one of the largest castle ruins in the western Rhineland-Palatine. Hardenburg Castle dominates the green hills along the road which follows the Eisenach River through the thick forested mountains of the Pflazer Wald Nature Park between Bad Durkheim and Kaiserslautern. The fortress castle at Hardenburg (not to be confused with Hardenberg in Lower-Saxony) was first constructed by the Counts of Leiningen-Hardenburg, on land belonging to the Benedictine monastery at Limburg a few miles away when Count Friedrich I of Leiningen wasgranted governorship of the abbey by King Phillip of Swabia in 1205. The abbots initially protested the building of the castle, but relented to the protectorship in 1249.

As the Leiningen family grew in stature and power (England’s Queen Victoria was a half-sister of Prince Karl of Leiningen in later days), the original 13th Century fortress was reconstructed in the Renaissance period into the large castle it appears today. It was built in red stone, typical of the area like the Burg Frankenstein ruin further west. Hardenburg Castle is probably best known for its “ball tower” with cannon balls imbedded in its stone masonry to impress any attackers of its impregnability to artillery. Unfortunately, it wasn’t really. The castle was taken by Napoleon’s army and most of its buildings were destroyed in 1795, leaving the great walls remaining. The Princes of Leiningen had already moved their primary residence to a more comfortable Baroque palace in Bad Durkheim.

A vaulted ceiling cellar and some other rooms are most of what remains of the living quarters of the castle. A distinctive feature of the castle is the great broad formal terrace of the former residence over-looking the wooded canyon of the Eisenach. It is located 30 minutes from Kaiserslautern. There is a road leading to a parking area near the ruin, and a hiking trail leads up from the village below from the parking lot of the modern town hall. The approach to the castle is fairly unique as the walking trail leads through a tunnel under the walls and along the slope above the river road below. The castle is open daily with a nominal admission charge. (Alexander Thon, ed. (2005), Wie Schwalbennester an den Felsen geklebt : Burgen in der Nordpfalz (in German) (1. ed.), Regensburg: Verlag Schnell und Steiner)

Hardenberg, 1580. Oldest known view of the castle. “Kurpfälzischen Sketchbook” (Staatsgalerie Stuttgart)

(Wolkenkratzer Photo)

Hardenburg, Bad Dürkheim.

(Muck Photo)

Hardenburg, Bad Dürkheim.

Burghausen

(Martin Falbisoner Photo)

Burghausen: (Burg zu Burghausen) seen from the Austrian side of the River Salzach. Between 1392 and 1503, the fortifications were extended around the entire castle hill. When the work was completed, Burghausen Castle became the strongest fortress of the region. Burghausen Castle in Burghausen, Upper Bavaria, Germany, is the longest castle complex in the world (1.051 km).

The castle hill was settled as early as the Bronze Age. The castle (which was founded before 1025) was transferred to the Wittelsbach family after the death of the last count of Burghausen, Gebhard II, in 1168. In 1180 they were appointed dukes of Bavaria and the castle was extended under Duke Otto I of Wittelsbach. With the first partition of Bavaria in 1255, Burghausen Castle became the second residence of the dukes of Lower Bavaria, the main residence being Landshut. The work on the main castle commenced in 1255 under Duke Henry XIII (1253–1290). In 1331 Burghausen and its castle passed to Otto IV, Duke of Lower Bavaria.

Under the dukes of Bavaria-landshut (1392-1503), the fortifications were extended around the entire castle hill. Beginning with Margarete of Austria, the deported wife of the despotic Duke Henry XVI (1393–1450), the castle became the residence of the Duke’s consorts and widows, and also a stronghold for the ducal treasures. In 1447 Louis VI, Duke of Bavaria, died in the castle as Henry’s prisoner. Under Duke Georg of Bavaria (1479–1503) the work was completed and Burghausen Castle became the strongest fortress of the region.

After the reunification of Bavaria in 1505 with the Landshut War of Succession, the castle had military importance, and due to the threat of the Ottoman Empire, it was subsequently modernised. During the Thirty Years; War, Gustav Horn was kept imprisoned in the castle from 1634 to 1641. After the Treaty of Teschen in 1779, Burghausen Castle became a border castle. During the Napoleonic Wars the castle suffered some destruction. The ‘Liebenwein tower’ was occupied by the painter Maximilian Liebenwein from 1899 until his death. He decorated the interior in the Art Nouveau style.

The Gothic castle comprises the main castle with the inner courtyard and five outer courtyards. The outermost point of the main castle is the Palas with the ducal private rooms. Today it houses the castle museum, including late Gothic paintings of the Bavarian State Picture Collection. On the town side of the main castle next to the donjon are the gothic inner Chapel of St. Elizabeth (1255) and the Dürnitz (knights’ hall) with its two vaulted halls. Opposite the Dürnitz are the wings of the Duchess’ residence. The first outer courtyard protected the main castle and also included the stables, the brewery and the bakery. The second courtyard houses the large Arsenal building (1420) and the gunsmith’s tower. This yard is protected by the dominant Saint George’s Gate (1494). The Grain Tower and the Grain Measure Tower were used for stabling and to store animal food; they belong to the third courtyard. The main sight of the fourth courtyard is the late Gothic outer Chapel of St. Hedwig (1479–1489). The court officials and craftsmen worked and lived in the fifth courtyard, which was once protected by a strong fortification. In 1800 this fortification was destroyed by the French under Michel Ney. The Pulverturm (“Powder Tower”, constructed before 1533) protected the castle in the western valley next to the Wöhrsee lake, an old backwater of the river. A battlement connects this tower with the main castle.

(Alexander Z Photo)

Berghausen Castle, maincourt from the 11th century.

(Bwag Photo)

(Alexander D. Photo)

Berghausen Castle, panoramic view.

(Werner Hölzl Photo)

Berghausen Castle, night view.

(Werner Hölzl Photo)

Berghausen Castle, night view.

(Christian Michelides Photo)

Burghausen Castle at night.

Gelnhausen

(Jürgen Regel Photo)

Gelnhausen: Imperial Palace, (Kaiserpfalz Gelnhausen, Pfalz Gelnhausen or Barbarossaburg), located on the

Kinzig river, in the town of Gelnhausen, Hesse. It was founded in 1170, and like the town whose creation was closely linked to the palace, goes back to Emperor Frederick I (Barbarossa). The palace enabled the expansion of imperial territory along an important long-distance highway, the Via Regia. Construction of the palace likely took place a few years before the official founding of the royal town in 1170. There may have been an earlier castle on the site that belonged to the Counts of Selbold-Gelnhausen. The construction of the palace was probably managed by the Counts of Büdingen, who erected the castle of Büdingen as their own residence nearby.

In 1180, the imperial palace at Gelnhausen was the venue for the great imperial court or Hoftag of Gelnhausen, at which Henry the Lion was put on trial in his absence and his imperial fiefs redistributed. In the years that followed, further imperial courts were convened at Gelnhausen. The now ruined palas may have been built for use as an assembly hall. Evidence of a large number of different stonemasons engaged in the construction suggests a relatively large number of labourers working on the building site at the same time and thus a rapid pace of construction.

During the Hohenstaufen era, the palace was an Imperial Castle (Reichsburg), had a burgrave and Burgmannen. Its estate included Büdingen Forest, which the castle’s occupants still retained timber rights (for construction and firewood) until the 19th century. The decline of the palace began as early as the 14th century when, in 1349, Emperor Charles IV (HRR) enfeoffed it, together with the town, to the Counts of Schwarzburg and never reclaimed it. In 1431, the Count of Hanau and Count Palatine Louis III procured the palace and town from Count Henry of Schwarzburg. At the end of the 16th century, the Counts of Isenburg in Birstein took over the burgrave’s office, but did not reside at the castle. During the Thirty Years’ War, the town and palace were severely damaged and Imperial and Swedish troops razed down its main building.

After the extinction of the House of Hanau in 1736, Gelnhausen fell to the Landgraves of Hesse-Kassel. The palace was then used as a quarry until 1811. The castle chapel had to be partly demolished due to its dilapidated condition. Around 1810, the palace became one of the first buildings from the epoch of Romanesque architecture in Germany that attracted the interest of art-loving scholars. At the end of the 19th century and during the 20th century, the first safety measures were carried out to preserve the remains of the palace for posterity. Likewise, it was not until the end of the 19th century that the previously independent municipality of Burg was dissolved and integrated into the town of Gelnhausen. Today, the palace belongs to the state of Hesse and is managed by the Administration of State Castles and Gardens for Hesse. Along with its attached castle museum, it is open to the public. (Waltraud Friedrich: Kulturdenkmäler in Hessen. Main-Kinzig-Kreis II.2. Gelnhausen, Gründau, Hasselroth, Jossgrund, Linsengericht, Wächtersbach. Published by the Landesamt für Denkmalpflege Hessen, Theiss, Wiesbaden/ Stuttgart, 2011)

Kaiserpfalz Gelnhausen reconstruction.

(Presse03 Photo)

Gelnhausen.

Kaiserpfalz Goslar

(Tobias Helfrich Photo)

Goslar: Imperial Palace (Kaiserpfalz Goslar) stands in the historic town of Goslar in Lower Saxony. It is the administrative centre of the district of Goslar and is located on the northwestern slopes of the Harz mountain range. Iron ore has been common in the Harz region since Roman times; the earliest known evidences for quarying and smelting date back to the 3rd century AD. The settlement on the Gose creek was first mentioned in a 979 deed issued by Emperor Otto II. It was located in the Saxon homelands of the Ottonian dynasty and a royal palace (Königspfalz) may already have existed at the site. It became even more important when extensive silver deposits were discovered at the nearby Rammelsberg, today a mining museum.

When Otto’s descendant Henry II began to convene Imperial synods at the Goslar palace from 1009 onwards, Goslar gradually replaced the Royal palace of Werla as a central place of assembly in the Saxon lands. This development was enforced by the Salian (Franconian) emperors. Conrad II, after his election as King of the Romans, celebrated Christmas 1024 in Goslar and had the foundations laid for the new Imperial Palace (Kaiserpfalz Goslar) the next year.

Goslar became the favourite residence of Conrad’s son Henry III who stayed at the palace about twenty times. Here he received King Peter of Hungary, as well as the emissaries of Prince Yaroslav of Kiev, and here he appointed bishops and dukes. His son and successor Henry IV was born here on 11 November 1050. Henry also had Goslar Cathedral built and consecrated by Archbishop Herman of Cologne in 1051. Shortly before his death in 1056, Emperor Henry III met with Pope Victor II in the church, emphasizing the union of secular and ecclesiastical power. His heart was buried in Goslar, his body in the Salian family vault in Speyer Cathedral. Only the northern porch of the cathedral has survived, as the main building was torn down in the early 19th century.

Under Henry IV, Goslar remained a centre of Imperial rule; however, conflicts intensified such as in the violent Precedence Dispute at Pentecost 1063. While Henry aimed to secure the enormous wealth deriving from the Rammlesberg silver mines as a royal demesne, the dissatisfaction of local nobles escalated with the Saxon Rebellion in 1073–75. In the subsequent Great Saxon Revolt, the Goslar citizens sided with anti-king Rudolf of Rheinfelden, who held a princely assembly there in 1077, and with Hermann of Salm, who was crowned king in Goslar by Archbishop Siegfried of Mainz on 26 December 1081. This brought Goslar the status of an Imperial City.

In the Spring of 1105, Henry V convened the Saxon estates at Goslar, to gain support for the deposition of his father Henry IV. Elected king in the following year, he held six Imperial Diets at the Goslar Palace during his rule. The tradition was adopted by his successor Lothair II and by the Hohenstaufen rulers, Conrad III and Frederick Barbarossa. After his election in 1152, King Frederick appointed the Welf duke Henry the Lion Imperial as the Vogt (bailiff) of the Goslar mines. In spite of this appointment, the dissatisfied duke besieged the town. A a meeting in Chiavenna in 1173, the duke demanded his enfeoffment with the estates in turn for his support on Barbarossa’s Italian campaigns. When Henry the Lion was finally declared deposed in 1180, he had the Rammelsberg mines destroyed.

Goslar’s importance as an Imperial residence began to decline under the rule of Barbarossa’s descendants. During the German throne dispute, the Welf king Otto IV laid siege to the town in 1198, but had to yield to the forces of his Hohenstaufen rival Philip of Swabia. Goslar was again stormed and plundered by Otto’s troops in 1206. Frederick II held the last Imperial Diet here; with the Great Interregnum upon his death in 1250, Goslar’s Imperial era ended. When the Emperors withdrew from Northern Germany, civil liberties in Goslar were strengthened. Market rights date back to 1025. A municipal council (Rat) was first mentioned in 1219. The citizens strived for control of the Rammelsberg silver mines and in 1267 joined the Hanseatic League. In addition to mining in the Upper Harz region, commerce and trade in Gose beer, later also slate and vitriol, became important. By 1290 the council had obtained Vogt rights, confirming Goslar’s status as a free imperial city. In 1340 its citizens were vested with Heeschild rights by Emperor Louis the Bavarian. The Goslar town law set an example for numerous other municipalities, like the Goslar mining law codified in 1359.

Early modern times saw both a mining boom and rising conflicts with the Welf Dukes of Brunswick-Lüneburg, mainly with Prince Henry V of Wolfenbüttel, who seized the Rammelsberg mines and extended Harz forests in 1527. Though a complaint was successfully lodged with the Reichskammergericht by the citizens of Goslar, a subsequent gruelling feud with the duke lasted for decades. Goslar was temporarily placed under Imperial ban, while the Protestant Reformation was introduced in the city by theologian Nicolaus von Amsdorf, who issued a first church constitution in 1531. To assert independence, in 1536 the citizens joined the Schmalkaldic League against the Catholic policies of the Habsburg emperor Charles V. The Schmalkaldic forces occupied the Wolfenbüttel lands of Henry V, but after they were defeated by Imperial forces in 1547 at the Batle of Mühlberg, the Welf duke continued his reprisals.

In 1577 the Goslar citizens signed the Lutheran Formula of Concord. After years of continued skirmishes, they finally had to grant Duke Henry and his son Julius extensive mining rights which ultimately edged out the city council. Nevertheless, several attempts by the Brunswick dukes to incorporate the Imperial city were rejected. Goslar and its economy was hit hard by the Thirty Years’ War, mainly by the Kipper und Wipper financial crisis in the 1620s which led to several revolts and pogroms. Facing renewed aggression by Duke Christian the Younger of Brunswick, the citizens sought support from the Imperial military leaders Tilly and Wallenstein. The city was occupied by the Swedish forces of King Gustavus Adolphus from 1632 to 1635. In 1642 a peace agreement was reached between Emperor Ferdinand III and the Brunswick duke Augustus the Younger. The hopes of the Goslar citizens to regain the Rammelsberg mines were not fulfilled. Goslar remained loyal to the Imperial authority, solemnly celebrating each accession of a Holy Roman Emperor.

While strongly referring to its great medieval traditions, the city continuously decreased in importance and got into rising indebtedness. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe stayed at Goslar in 1777. First administrative reforms were enacted by councillors of the Siemens family. In spite of this, the status of Imperial immediacy was finally lost, when Goslar was annexed by Prussian forces during the Napoleonic Wars in 1802, and confirmed by the German Mediatisation the next year. Under Prussian rule, further reforms were pushed ahead by councillor Christian Wilhelm von Dohn. Goslar was temporarily part of the Kingdom of Westphalia upon the Prussian defeat at the 1806 Battle of Jena-Auerstedt. Goslar finally was assigned to the newly established Kingdom of Hanover by resolution of the Vienna Congress. The cathedral was sold and torn down between 1820 and 1822. Goslar again came under Prussian rule after the Austro-Prussian War of 1866. It became a popular retirement residence (Pensionopolis) and a garrison town of the Prussian Army. The Hohenzollern kings and emperors had the Imperial Palace restored, including the mural paintings by Hermann Wislicenus.

After the Nazis came to power in 1933, Reich Minister Richard Walther Darré made Goslar the seat of the agricultural Reichsnährstand corporation. In 1936, the city obtained the title of Reichsbauernstadt. In the course of Germany’s rearmament, a Luftwaffe airbase was built north of the town and several war supplier companies were located in the vicinity, including subcamps of the Buchenwald and Neuengamme concentration camps. Nevertheless, the historic town escaped strategic bombing during the Second World War. Goslar was part of the British occupation zone from 1945, and the site of a displaced persons camp. During the Cold War era, because the city stood near the inner German border, it was a major garrison town for the West German army army, border police and French Forces in Germany. After the fall of the Berlin wall, the barracks were vacated and a major economic factor was lost. The Rammelberg mines were finally closed in 1988, after a millennial history of mining. (Wikipedia)

(Natalia19 Photo)

The wide gates of Goslar.

(Anaconda74 Photo)

Goslar, Lower Saxony, Artillery tower “Zwinger”, built in 1517. The walls are up to 6,5 meters thick. On the right

is an earthen rampart which surrounded the older stone wall as protection against gun fire.

Burg Greifenstein

(Oliver Abels Photo)

Greifenstein: Burg Greifenstein lies in the village of Greifenstein in the county of Lah-Dill-Kries in Middle Hesse. The castle stands on a hill in the Dill Westerwald and commands a good view over the Dill valley. At 441 m (1,447 ft) above sea level, it is the highest castle in the county of Lahn-Dill and a very visible landmark. The hill castle was first recorded in 1160. In 1298 it was destroyed by the counts of Nassau and Solms, along with Lichtenstein, which was not rebuilt. In 1315 it was enfeoffed by the House of Habsburg (Albert I had purchased the castle from Kraft of Greifenstein) to the Counts of Nassau. After having several owners, it had deteriorated by 1676. It was then converted into a Baroque schloss by William Maurice of Solms-Greifenstein. After the counts moved to Braunfels in 1693, the site fell into ruins.

In 1969 the castle ruins were gifted to the Greifenstein Society, who have since looked after the preservation of the site, which is open to the public and incorporates a restaurant. Since 1995, its restoration has also been supported by the Federal Republic of Germany, because it has been classified as a Monument of National Significances (Denkmal von nationaler Bedeutung).

The circular walk across the castle terrain leads to a gaol with torture implements, weapons and a wine cellar, living rooms and a twin-towered bergfried accessible via a spiral staircase. On the pointed roof of the Brother Tower (Bruderturm) there is a gryphon (Greif, a reference to the name of the castle), which serves as a weather vane. There is a peal of three bells in the tower, with strike tones of F#1, A1 and C2.

Attractions include the Village and Castle Museum (Dorf- und Burgmuseum), one of the few double chapels in Germany. The Chapel of St. Catherine was built in 1462 as a fortified church in the Gothic style. When the castle was converted into the Baroque style the castle courtyard was filled with earth with the result that, today, the chapel is below ground level. It contains frescoes and arrow slits, as well as casemates with vaulted ceilings and fighting rooms. The Baroque church built above the fortified chapel from 1687 to 1702 is richly decorated with stucco and is of the Italian Early Baroque period. The upper and lower churches are linked by a staircase. Walks around the castle and an educational herb garden make the site a popular destination. (Rudolf Knappe: Mittelalterliche Burgen in Hessen: 800 Burgen, Burgruinen und Burgstätten. 3rd edn., Wartberg-Verlag, Gudensberg-Gleichen, 2000)

Burg Greifenstein, Matthäus Merian, 1655.

(Michael J. Zirbes Photo)

Aerial view of Burg Greifenstein.

(Karlunun Photo)

Burg Greifenstein.

Schloss Neuschwanstein

(Author’s artwork)

Although it is not medieval, many Canadians are familiar with Neuschwanstein Castle. it is actually a 19th-century palace built on a rugged hill of the foothills of the Alps in the very south of Germany, near the border with Austria. It is located in the Swabia region of Bavaria, in the municipality of Schwangau, above the incorporated village of Hohenschwangau, which is also the location of Hohenschwangau Castle. The closest larger town is Füssen. The castle stands above the narrow gorge of the Pöllat stream, east of the Alpsee and Schwansee lakes, close to the mouth of the Lech into Forggensee.

Despite the main residence of the Bavarian monarchs at the time, the Munich Residenz, being one of the most extensive palace complexes in the world, King Ludwig II of Bavaria felt the need to escape from the constraints he saw himself exposed to in Munich, and commissioned Neuschwanstein Castle on the remote northern edges of the Alps as a retreat but also in honour of composer Richard Wagner, whom he greatly admired.

Ludwig chose to pay for the palace out of his personal fortune and by means of extensive borrowing rather than Bavarian public funds. Construction began in 1869 but was never completed. The castle was intended to serve as a private residence for the king but he died in 1886, and it was opened to the public shortly after his death. Since then, more than 61 million people have visited Neuschwanstein Castle. More than 1.3 million people visit annually, with as many as 6,000 per day in the summer. Designated since July 2025 as a cultural World Heritage Site, the castle is open to the general public through guided tours. (Wikipedia)