Medieval Castles, Fortresses and Châteaux in France

(Roman Geber Photo)

Château Gaillard is a medieval castle ruin overlooking the River Seine above the commune of Les Andelys, in

the French department of Eure, in Normandy. It is located some 95 kilometres (59 mi) north-west of Paris and 40

kilometres (25 mi) from Rouen. Construction began in 1196 under the auspices of Richard the Lionheart, who was simultaneously King of England and feudal Duke of Normandy. The castle was expensive to build, but the majority

of the work was done in an unusually short period of time. It took just two years and, at the same time, the town

of Petit Andely was built. Château Gaillard has a complex and advanced design, and uses early principles of

concentric fortification; it was also one of the earliest European castles to use machicolations (mâchicoulis).

(These are floor openings between the supporting corbels of a battlement, through which stones or other material,

such as boiling water or boiling cooking oil, could be dropped on attackers at the base of a defensive wall). The

castle consists of three enclosures separated by dry moats, with a keep in the inner enclosure.

Château Gaillard was captured in 1204 by the king of France, Philip II, after a lengthy siege. In the mid-14th

century, the castle was the residence of the exiled David II of Scotland. The castle changed hands several times

in the Hundred Years’ War, but in 1449 the French king captured Château Gaillard from the English king

definitively, and from then on it remained in French ownership. Henry IV of France ordered the demolition of

Château Gaillard in 1599. Although it was in ruins at the time, it was felt to be a threat to the security of the local

population. The castle ruins are listed as a monument historique by the French Ministry of Culture. The inner

bailey is open to the public from March to November, and the outer baileys are open all year.

Richard the Lionheart inherited Normandy from his father, Henry II, in 1189 when he ascended to the throne of

England. There was a rivalry between the Capetians and the Plantagenêts. Richard as the Plantagenêt king of

England was more powerful than the Capetian king of France, despite the fact that Richard was a vassal of the

French king and paid homage for his lands in the country. From 1190 to 1192, Richard the Lionheart took part

in the Third Crusade. He was joined by Philip II of France, as each was wary that the other might invade his

territory in his absence. Richard was captured and imprisoned on the return journey to England, and he was not

released until 4 February 1194. In Richard’s absence, his brother John revolted with the aid of Philip; amongst

Philip’s conquests in the period of Richard’s imprisonment was the Norman Vexin (an historical county of

northwestern France), and a few towns nearby, including Le Vaudreuil, Verneuil and Évreux. It took Richard

until 1198 to reconquer a part of it.

Château Gaillard stands high above the River Seine, an important transport route and on the site of a naturally

defendable position. The town of Grand Andely rests in the valley below the site. Under the terms of the Treaty

of Louviers (January 1196) between Richard and Philip II, neither king was allowed to fortify the site. In spite

of this treaty, Richard decided to build a castle at Andeli. Its purpose was to protect the duchy of Normandy from

Philip II, and it helped fill a gap in the Norman defences left by the fall of Château Gisors, and above all Château

de Gaillon, a castle which belonged to Philip and used as an advanced French fortification to block the Seine valley.

Château Gaillard also served as a base from which Richard could launch his campaign to take back the Norman

Vexin from French control. Les Andelys is located just in front of Gaillon on the other side of the Seine valley.

Richard tried to obtain the manor through negotiation. Walter de Coutances, Archbisho of Rouen, was reluctant

to sell the manor as it was one of the diocese’s most profitable, and other lands belonging to the diocese had

recently been damaged by war. When Philip besieged Aumale in northern Normandy, on the border with Picardy,

Richard grew tired of waiting and seized the manor, although the act was opposed by the Church.

In an attempt to get Pope Celestine III to intercede, Walter de Coutances left for Rome in November 1196.

Richard sent a delegation to represent him in Rome. One of the party, Richard’s, Lord Chancellor William

Longchamp (who was also Bishop of Ely), died during the journey, although the rest, including Philip of Poitou,

Bishop of Durham, and Guillaume de Ruffière, Bishop of Lisieux, arrived in Rome. Walter de Coutances

meanwhile issued an interdict against the Duchy of Normandy, which prohibited church services from being

performed in the region. Roger of Howden detailed “the unburied bodies of the dead lying in the streets and

square of the cities of Normandy”. Construction began with the interdict hanging over Normandy, but it was later

repealed in April 1197 by Celestine, after Richard made gifts of land to Walter de Coutances and the diocese of

Rouen, including two manors and the prosperous port of Dieppe. The site of Château Gaillard had not been fortified

before, and the town of Petit Andely was constructed at the same time; together with the historical Grand Andely,

the two are known as Les Andelys. The castle sits on a high limestone promontory, 90 m above Les Andelys and

overlooking a bend in the River Seine. The castle was connected with Les Andelys through a series of

contemporary outworks.

During King Richard’s reign, the Crown’s expenditure on castles declined from the levels spent by Henry II,

Richard’s father, although this has been attributed to a concentration of resources on Richard’s war with the king

of France. The work at Château Gaillard cost an estimated £12,000 between 1196 and 1198. Richard only spent a

n estimated £7,000 on castles in England during his reign, similar as his father Henry II. The Pipe rolls (a

collection of financial records maintained by the English Exchequer), for the construction of Château Gaillard

contain the earliest details of how work was organised in castle building and what activities were involved.

Among those workmen mentioned in the rolls are miners, stone cutters, quarrymen, masons, lime-workers,

carpenters, smiths, hodmen, water carriers, soldiers to guard the workers, diggers who cut the ditch surrounding

the castle, and carters who transported the raw materials to the castle. A master-mason is omitted, and military

historian Allen Brown has suggested that it may be because Richard himself was the overall architect; this is

supported by the interest Richard showed in the work through his frequent presence.

Not only was the castle built at considerable expense, but it was built relatively rapidly. Construction of large

stone castles often took the better part of a decade. The work at Dover castle, for example, took place between

1179 and 1191 (at a cost of £7,000). Richard was present during part of the construction to ensure work proceeded

at a rate he was happy with. According to William of Newburgh, in May 1198 Richard and the labourers working

on the castle were drenched in a “rain of blood”. While some of his advisers thought the rain was an evil omen,

Richard was undeterred: “the king was not moved by this to slacken one whit the pace of work, in which he took s

uch keen pleasure that, unless I am mistaken, even if an angel had descended from heaven to urge its abandonment

he would have been roundly cursed”.

After just a year, Château Gaillard was approaching completion and Richard remarked “Behold, how fair is this

year-old daughter of mine!” Richard later boasted that he could hold the castle “were the walls made of butter”.

By 1198, the castle was largely completed. At one point, the castle was the site of the execution of three soldiers

of the king of France in retaliation for a massacre of Welsh mercenaries ambushed by the French. The three were

thrown to their deaths from the castle’s position high above the surrounding landscape. In his final years, the

castle became Richard’s favourite residence, and writs and charters were written at Château Gaillard, bearing

“apud Bellum Castrum de Rupe” (at the Fair Castle of the Rock). Richard did not enjoy the benefits of the castle

for long, however, as he died in Limousin on 6 April 1199, from an infected arrow wound to his shoulder, sustained

while besieging Châlus.

After Richard’s death, King John of England failed to effectively defend Normandy against Philip’s ongoing

campaigns between 1202 and 1204. Château de Falaise fell to Philip’s forces, as well as castles from Mortain to

Pontorson, while Philip simultaneously besieged Rouen,which capitulated to French forces on 24 June 1204,

effectively ending Norman independence. Philip laid siege to Château Gaillard, which was captured after a long

siege from September 1203 to March 1204. As Philip continued the siege throughout the winter and King John

made no attempt to relieve the castle, it was only a matter of time before the castellan was forced to capitulate.

The main source for the siege is Philippidos, a poem by William the Breton, Philip’s chaplain. As a result, modern

scholars have paid little attention to the fate of the civilians of Les Andelys during the siege.

The local Norman population sought refuge in the castle to escape from the French soldiers who ravaged the town.

The castle was well supplied for a siege, but the extra mouths to feed rapidly diminished the stores. Between

1,400 and 2,200 non-combatants were allowed inside, increasing the number of people in the castle at least

five-fold. In an effort to alleviate the pressure on the castle’s supplies, Roger de Lacy, the castellan, evicted 500

civilians. This first group was allowed to pass through the French lines unhindered, and a second group of similar

size did the same a few days later. Philip was not present, and when he learned of the safe passage of the civilians,

he forbade further people being allowed through the siege-lines. The idea was to keep as many people as possible

within Château Gaillard to drain its resources. Roger de Lacy evicted the remaining civilians from the castle, at

least 400 people, and possibly as many as 1,200. The group was not allowed through, and the French opened fire

on the civilians, who turned back to the castle for safety, but found the gates locked. They sought refuge at the

base of the castle walls for three months; over the winter, more than half their number died from exposure and

starvation. Philip arrived at Château Gaillard in February 1204, and ordered that the survivors should be fed and

released. Such treatment of civilians in sieges was not uncommon, and such scenes were repeated much later at

the sieges of Calais in 1346 and Rouen in 1418–1419, both in the Hundred Years’ War.

The French gained access to the outermost ward by undermining its advanced main tower. Following this, Philip

ordered a group of his men to look for a weak point in the castle. They gained access to the next ward when a

soldier named Ralph found a latrine chute in use through which the French could clamber into the chapel. After

ambushing several unsuspecting guards, and setting fire to the buildings, Philip’s men then lowered the movable

bridge and allowed the rest of their army into the castle. The Anglo-Norman troops retreated to the inner ward.

After a short time the French successfully breached the gate of the inner ward, and the garrison retreated finally

to the keep. With supplies running low Roger de Lacy and his garrison of 20 and 120 other soldiers surrendered

to the French army, bringing the siege to an end on 6 March 1204. In drawn-out medieval sieges, contemporary

writers often emphasised the importance of dwindling supplies in the capitulation of the garrison, as was the case

with the Siege of Château Gaillard. With the castle under French control, the main obstacle to the French entering

the Seine valley was removed. They were able to enter the valley unmolested and take Normandy. Thus, for the

first time since it had been given as a duchy to Rollo in 911, Normandy was directly ruled by the French king.

The city of Rouen surrendered to Philip II on 23 June 1204. After that, the rest of Normandy was easily conquered

by the French.

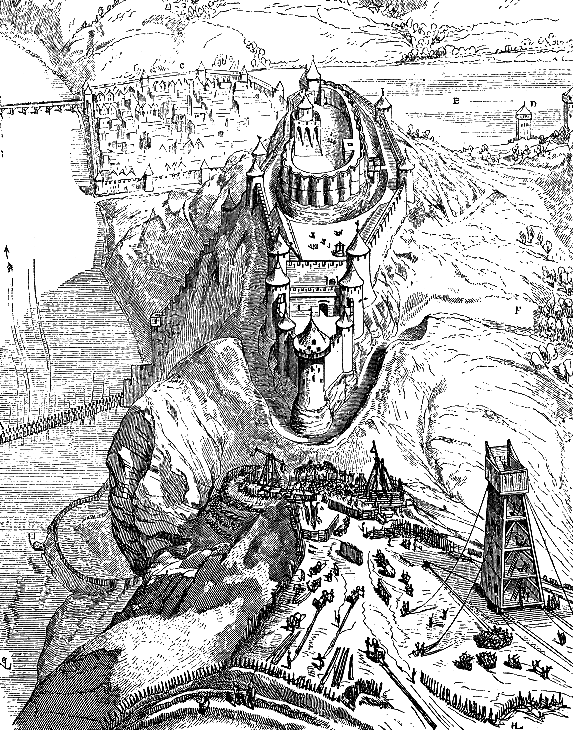

An impression by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, a 19th-century architect experienced in renovating castles, of how the

Siege of Château Gaillard would have looked.

In 1314, Château Gaillard was the prison of Margaret and Blanche of Burgundy, future queens of France. They

had been convicted of adultery in the Tour de Nesle Affair, and after having their heads shaved they were locked

away in the fortress. Following the Scottish defeat at the Battle of Halidon Hill in 1333 during the Second War of

Scottish Independence, the child-king David II and certain of his court were forced to flee to France for safety.

At the time, southern Scotland was occupied by the forces of King Edward III of England. David, then nine years

old, and his bride Joan of the Tower, the twelve-year-old daughter of Edward II, were granted the use of Château

Gaillard by Philip VI. It remained their residence until David’s return to Scotland in 1341. David did not stay

out of English hands for long after his return; he was captured after the Battle of Neville’s Cross in 1346 and

endured an eleven-year captivity in the Tower of London.

During the Hundred Years’ War between the English and French crowns, possession of the castle switched several

times. Château Gaillard, along with Château de Gisors, Ivry-la-Bataille and Mont Saint-Michel, was one of four

castles in the Normandy which offered resistance to Henry V of England in 1419, after the capitulation of Rouen

and much of the rest of the Duchy. Château Gaillard was besieged for a year before it was surrendered to the

English in December 1419. All the resisting castles except Mont Saint-Michel eventually fell, and Normandy

was temporarily returned to English control. Étienne de Vignolles, a mercenary (routier) known as La Hire, then

re-captured Château Gaillard for the French in 1430. However, the English were revived by the capture and

execution of Joan of Arc, and although by then the war was turning against them, a month later they captured

Château Gaillard again.

(Illustration by Paul Lehugeur 1854-1916)

Joanof Arc leading a siege on a city in the 15th Century.

When the French gained ascendancy again between 1449 and 1453 the English were

forced out of the region, and in 1449 the castle was taken by the French for the last time.

By 1573, Château Gaillard was uninhabited and in a ruinous state, but it was still believed that the castle posed a

threat to the local population if it was repaired. Therefore, at the request of the French States-General, King Henry IV

ordered the demolition of Château Gaillard in 1599. Some of the building material was reused by Capuchin monks

who were granted permission to use the stone for maintaining their monasteries. In 1611, the demolition of

Château Gaillard came to an end. The site was left as a ruin, and in 1862 was classified as a monument historique.

In 1962, a conference on the contributions of the Normans to medieval military architecture was held at Les Andelys.

Allen Brown attended the conference and remarked that the castle was “in satisfying receipt of skilful care and

attention”. The journal Château Gaillard: Études de Castellogie Médiévale, which was published as a result of

the conference, has since run to 23 volumes, based on international conferences on the subject of castles. In the 1990s,

archaeological excavations were carried out at Château Gaillard. The excavations investigated the north

of the fortress, searching for an entrance postulated by architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, but no such entrance was

found. However, the excavation did reveal that there was an addition to the north of the castle to enable the use

of guns. Typologically, the structure has been dated to the 16th century.

The conclusion of the excavations was that the site had “enormous archaeological potential”, but that there were

still unanswered questions about the castle. After Philip II took Chateau Gaillard, he repaired the collapsed tower

of the outer bailey that had been used to gain access to the castle. The archaeological investigation examined the

tower generally thought to be the one collapsed by Philip, and although it did not recover any dating evidence, the

consensus is that he completely rebuilt the tower. In conjunction with the archaeological work, efforts were made

to preserve the remaining structures. Today, Château Gaillard’s inner bailey is open to the public from March to

November, while the outer baileys are open all year round.

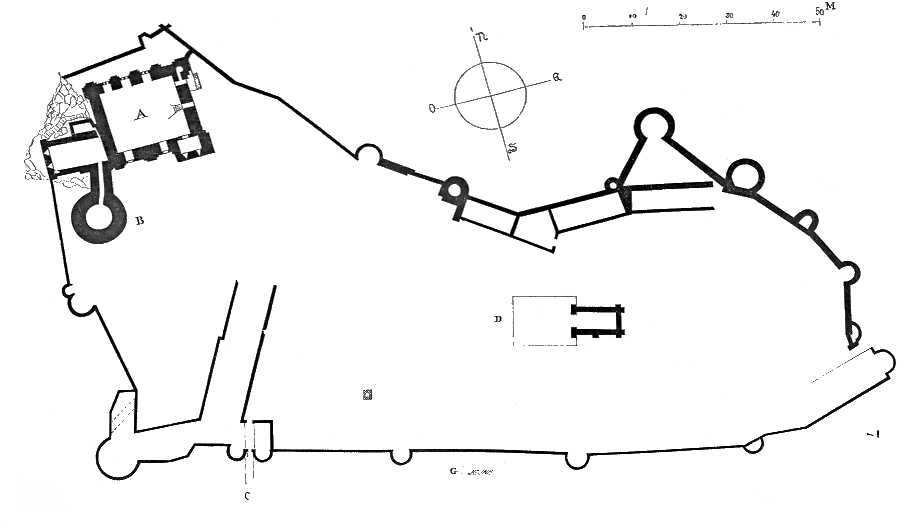

Château Gaillard consists of three baileys, an inner, a middle, and an outer with the main entrance to the castle,

and a keep, also called a donjon, in the inner-bailey. The baileys, which were separated by rock-cut ditches,

housed the castle’s stables, workshops, and storage facilities. It is common for extant castles to be the result of

several phases of construction, and to be adapted and added to over the period of their use. Château Gaillard,

however, is essentially the result of one period of building. The division into three wards bears similarities with

the design of Château de Chinon, built by Henry II in the mid-12th century on a promontory overlooking a town.

The outer bailey is the southernmost feature of the castle. It is pentagon shaped, and there are five towers spaced

along the wall, three of which are at corners. North of the outer bailey is the middle bailey which is an irregular

polygon. Like the outer bailey, the wall of the middle bailey is studded with towers. The towers allowed the

garrison to provide enfilading fire. In the fashion of the time. Most of the towers in the curtain walls of the

middle and outer baileys were cylindrical. Château Gaillard was one of the first castles in Europe to use

machicolations, stone projections on top of a wall with openings that allowed objects to be dropped on an enemy

at the base of the wall. Machicolations were introduced to Western architecture as a result of the Crusades. Until

the 13th century, the tops of towers in European castles had usually been surrounded by wooden galleries, which

served the same purpose as machicolations. An Eastern innovation, they may have originated in the first half of

the 8th century.

Within the middle bailey was the inner bailey. The gatehouse from the middle to the inner-bailey was one of the

earliest examples of towers flanking the entrance to remove the blind-spot immediately in front of the gate. This

was part of a wider trend from around the late 12th or 13th century onwards for castle gateways to be strongly

defended. The design of the inner bailey, with its wall studded with semi-circular projections, is unparalleled.

This innovation had two advantages: firstly, the rounded wall absorbed the damage from siege engines much

better as it did not provide a perfect angle to aim at; secondly, the arrowslits in the curved wall allowed arrows

to be fired at all angles. The inner bailey, which contained the main residential buildings, used the principles of

concentric defence. This and the unusual design of the inner bailey’s curtain wall meant that castle was advanced

for its age, since it was built before concentric fortification was fully developed in Crusader castles such as Krak

des Chevaliers. Concentric castles were widely copied across Europe. When Edward I of England, who had himself

been on Crusade, built castles in Wales in the late 13th century, four of the eight he founded were concentric.

The keep was inside the inner bailey and contained the king’s accommodation. It had two rooms: an antechamber

and an audience room. While Allen Brown interpreted the audience room as the king’s chamber, historian Liddiard

believes it is probably a throne room. A throne room emphasises the political importance of the castle. In England

there is nothing similar to Château Gaillard’s keep, but there are buildings with a similar design in France in the 12th

and 13th centuries.

Allen Brown described Château Gaillard as “one of the finest castles in Europe” and the military historian Sir

Charles Oman wrote in 1924 that: “Château Gaillard, as we have already had occasion to mention, was

considered the masterpiece of its time. The reputation of its builder, Coeur de Lion, as a great military engineer

might stand firm on this single structure. He was no mere copyist of the models he had seen in the East, but

introduced many original details of his own invention into the stronghold”.

Despite Château Gaillard’s reputation as a great fortress, Liddiard highlights the absence of a well in the keep as

a peculiar weakness, and the castle was built on soft chalk, which would have allowed the walls to be undermined.

But other sources evoke the presence of three wells in the three different baileys and the soft chalk does not really

weaken the very thick walls. Its weakness is more the result of its location (higher hill behind), its extension (more

than 200 metres (660 ft)) on a long narrow ridge and the difficulties in linking up the different baileys to allow a

good communication and to secure an efficient defence without a large garrison.

Château Gaillard was important not solely as a military structure, but as a salient symbol of the power of Richard

the Lionheart. It was a statement of dominance by Richard, having reconquered the lands Philip II had taken.

Castles such as Château Gaillard in France, and Dover in England, were amongst the most advanced of their age,

but were surpassed in both sophistication and cost by the works of Edward I of England in the latter half of the

13th century. (Friar, Stephen (2003), The Sutton Companion to Castles, Stroud: Sutton Publishing), (Liddiard, Robert

(2005), Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Landscape, 1066 to 1500, Macclesfield: Windgather Press Ltd)

(Urban Photo)

The keep of Château Gaillard.

(Philippe Alès Photo)

Château Gaillard.

(Olivier Cambus Photo)

Aerial view of Château Gaillard.

(Sylvan Verlaine Photo)

Aerial view of Château Gaillard.

(Michel Cheron Photo)

Château Gaillard.

(Casper Moller Photo)

Château Gaillard.

(ignis Photo)

Château de Foix (Castèl de Fois) is a castle which dominates the town of Foix in the French départment of Ariège.

An important tourist site, it is known as a centre of the Cathars. It has been listed since 1840 as a monument

historique by the French Ministry of Culture.

Built In the style of 7th-century fortification, the castle is known from 987. In 1002, it was mentioned in the will

of Roger I, Count of Carcassone, who bequeathed the fortress to his youngest child, Bernard. In effect, the family

ruling over the region were installed here which allowed them to control access to the upper Ariège valley and to

keep surveillance from this strategic point over the lower land, protected behind impregnable walls. In 1034, the

castle became the capital of the County of Foix, and played a decisive role in medieval military history. During

the two following centuries, the castle was home to Counts with shining personalities who became the soul of the

Occitan resistance during the crusade against the Albigensians. The county became a privileged refuge for

persecuted Cathars.

The castle, often besieged (notably by Simon de Montfort in 1211 and 1212), resisted assault and was only taken

once, in 1486, thanks to treachery during the war between two branches of the Foix family. From the 14th century,

the Counts of Foix spent less and less time in the uncomfortable castle, preferring the Governors’ Palace (Palais

des gouverneurs). From 1479, the Counts of Foix became Kings of Navarre and the last of them, Henri IV of

France, annexed his Pyrrenean lands to France. As seat of the Governor of the Foix region from the 15th century,

the castle continued to ensure the defence of the area, notably during the Wars of Religion. Alone of all the castles

in the region, it was exempted from the destruction orders of Richelieu (1632-1638).

Until the Revolution, the fortress remained a garrison. Its life was brightened with grand receptions for its

governors, including the Count of Tréville, captain of musketeers under Louis XIII and Marshal Philippe Henri

de Ségur, one of Louis XVI’s ministers. The Round Tower, built in the 15th century, is the most recent, the two

square towers having been built before the 11th century. They served as a political and civil prison for four

centuries until 1862.

Since 1930, the castle has housed the collections of the Ariège départemental museum. Sections on prehistory,

Gallo-Roman and mediaeval archaeology tell the history of Ariège from ancient times. Currently, the museum is

rearranging exhibits to concentrate on the history of the castle site so as to recreate the life of Foix at the time of

the Counts. (AUÉ, Michèle (1992). Discover Cathar Country. Pleasance, Simon (trans.). Vic-en-Bigorre, France: MSM)

(Jean Louis Venet Photo)

Château de Foix.

(Patrick Castay Photo)

Château de Foix.

(BLUMJ Photo)

Château de Foix.

(Krzysztof Golik Photo)

Château de Foix.

(Nitot Photo)

Château de Falaise is a castle located in the south of the commune of Falaise (cliff) in the department of Calvados,

in the region of Normandy, France. William the Conqueror, the son of Duke Robert of Normandy, was born in an

earlier castle on the same site in about 1028. William went on to conquer England and become king, and possession

of the castle descended through his heirs until the 13th century when it was captured by King Philip II of France.

Possession of the castle changed hands several times during the Hundred Years’ War. The castle was abandoned

during the 17th century. Since 1840 it has been protected as a monument historique.

On the death of Richard II, Duke of Normandy, in August 1026 his son (also called Richard) succeeded to the duchy.

The inheritance however was disputed by Richard III’s younger brother, Robert. Not content with his inheritance

of the town of Exmes and its surrounding area, Robert rebelled and took up arms against his brother and he captured

the castle of Falaise. Richard besieged the castle and forced Robert to submit to him, however the duke died from

unknown causes in 1027 and was succeeded by his brother. Robert fathered an illegitimate son by a woman named

Herleva, who was from the town of Falaise and the daughter of a chamberlain. The child, William, was born in

about 1028.

The castle (12th–13th century), which overlooks the town from a high crag, was formerly the seat of the Dukes of

Normandy. The construction was started on the site of an earlier castle in 1123 by Henry I of England, with the

large keep (grand donjon). Later was added the “small keep” (petit donjon). The tower built in the first quarter

of the 12th century contained a hall, chapel, and a room for the lord, but no small rooms for a complicated household

arrangement; in this way, it was similar to towers in England at Corfe, Norwich and Portchester.

Arthur I, Duke of Brittany, was King John of England’s teenage nephew, and a rival claimant to the throne of

England. With the support of King Philip II of France, Arthur embarked on a campaign in Normandy against

John in 1202, and Poitou revolted in support of Arthur. The Duke of Brittany besieged his grandmother, Eleanor

of Aquitaine, in the Château de Mirebeau. John marched on Mirebeau, taking Arthur by surprise and capturing

him on 1 August. From there Arthur was conveyed to Falaise where he was imprisoned in the castle’s keep.

According to contemporaneous chronicler Ralph of Coggeshall, John ordered two of his servants to mutilate the

duke. Hugh de Burgh was in charge of guarding Arthur and refused to let him be mutilated, but to demoralise

Arthur’s supporters, announced his death. The circumstances of Arthur’s death are unclear, though he probably died in 1203.

In about 1207, after having conquered Normandy, Philip II Augustus ordered the building of a new cylindrical keep.

It was later named the Talbot Tower (Tour Talbot) after the English commander responsible for its repair during the

Hundred Years’ War. It is a tall round tower, similar design to the towers built at Gisors and the medieval Louvre.

Possession of the castle changed hands several times during the Hundred Years’ War. The castle was deserted

during the 17th century.

A programme of restoration was carried out between 1870 and 1874. The castle was damaged during a

bombardment during the Second World War in the battle for the Falaise pocket in 1944, but the three keeps were

unscathed.

(Ollamh Photo)

Château de Falaise.

(rene boulay Photo)

Château de Falaise.

(rene boulay Photo)

Château de Falaise.

Ground plan of Château de Falaise.

(Brady Benot Photo)

Château de Falaise.

(Brady Benot Photo)

Château de Falaise.

(Viault Photo)

Aerial view of Château de Falaise.

(Nitot Photo)

Chateau-de-Gisors, Eure, Normandy, France. The castle was a key fortress of the Dukes of Normandy in the 11th

and 12th centuries. It was intended to defend the Anglo-Norman Vexin territory from the pretensions of the King

of France. In 1193, while King Richard I of Enlgand (also Duke of Normandy) was imprisoned in Germany, the

castle fell into the hands of King Philip II of France. After Richard’s death in 1199, Philip conquered much of the

rest of Normandy and Gisors thereafter lost a good part of its importance as a frontier castle. The castle is also

known for its links with the Templars. Put into their charge by the French king between 1158 and 1160, it became

the final prison of the Grand Master of the Order, Jacques de Molay, in 1314. Although it has been estimated that

the bailey could have housed 1,000 soldiers, in 1438 (during the Hundred Years’ War) the English garrison

numbered just 90. By 1448, this had decreased to 43.

The first building work is dated to about 1095, and consisted of a motte, which was enclosed in a spacious

courtyard or bailey. Henry I of England, Duke of Normandy, added an octagonal stone keep to the motte. After

1161, important reinforcement work saw this keep raised and augmented; the wooden palisade of the motte

converted to stone, thus forming a chemise; and the outer wall of the bailey was completed in stone with flanking

towers. The octagonal keep is considered one of the best preserved examples of a shell keep. A second keep,

cylindrical in shape, called the Prisoner’s Tower (tour du prisonnier), was added to the outer wall of the castle at

the start of the 13th century, following the French conquest of Normandy. Further reinforcement was added

during the Hundred Years’ War. In the 16th century, earthen ramparts were built.

(Gi.bareau Photo)

Chateau-de-Gisors.

(Pierre Poschadel Photo)

Chateau-de-Gisors.

(CJ DUB Photo)

Chateau-de-Gisors.

(Patrick Rock Photo)

Chateau-de-Gisors, the keep, Eure, Normandy, France.

(Marc Ryckaert Photo)

The Château d’Angers is acastle in the city of Angers in the Loire Valley, in the département of Maine-et-Loire,

in France. Founded in the 9th century by the Counts of Amjour, it was expanded to its current size in the 13th

century. It is located overlooking the river Maine. It has been listed as a historical monument since 1875. Now

open to the public, the Château d’Angers is home of the Apocalypse Tapestry.

Originally, the Château d’Angers was built as a fortress at a site inhabited by the Romans because of its strategic

defensive location. In the 9th century, the Bishop of Angers gave the Counts of Anjou permission to build a castle

in Angers. The construction of the first castle began under Count Fulk III (970–1040), who was celebrated for his

construction of dozens of castles. He built Château d’Angers to protect Anjou from the Normans. It became part

of the Angevin Empire of the Plantagenet Kings of England during the 12th century. In 1204, the region was

conquered by Philip II, and the new castle was constructed during the minority of his grandson, Louis IX (Saint

Louis) in the early part of the 13th century. Louis IX rebuilt the castle in whitestone and black slate, with 17

semicircular towers. The construction undertaken in 1234 cost 4,422 livres, roughly one per cent of the estimated

royal revenue at the time. Louis gave the castle to his brother, Charles in 1246.

In 1352, King John II le Bon, gave the castle to his second son, Louis, who later became the Count of Anjou. He

married the daughter of the wealthy Duke of Brittany, and with her wealth, Louis had the castle modified. In 1373,

he commissioned the famous Apocalypse Tapestry, from from a work of art the painted by Hennequin de Bruges,

and the Parisian tapestry-weaver Nicolas Bataille. Louis II (Louis I’s son) and Yolande d’Aragon, added a chapel

(1405–12) and royal apartments to the complex. The chapel is a sainte chapelle, the name given to churches which

enshrined a relic of the Passion. The relic at Angers was a splinter of the fragment of the True Cross which had

been acquired by Louis IX.

In the early 15th century, the hapless dauphin who, with the assistance of Joan of Arc would become King

Charles VII, had to flee Paris and was given sanctuary at the Château d’ Angers.

In 1562, Catherine de Medici, had the castle restored as a powerful fortress, but her son, Henry III, reduced the

height of the towers and had the towers and walls stripped of their embattlements. Henry III then used the castle

stones to build streets and develop the village of Angers. Because of the threat of attacks from the Hugenots,

however, the king maintained the castle’s defensive capabilities by making it a military outpost and by installing

artillery on the château’s upper terraces. At the end of the 18th century, as a military garrison, it showed its worth

when its thick walls withstood a massive bombardment by cannons from the Vendean army. Unable to do defeat

the walls, the invaders withdrew.

A military academy was established in the castle to train young officers in the strategies of war. Arthur Wellesley,

1st Duke of Wellington, best known for taking part in the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte at the Battle of Waterloo

in 1815, was trained at the Military Academy of Angers. The academy was later moved to Saumur and the castle

was used for the rest of the 19th century as a prison, powder magazine and barracks.

The castle continued to be used as an armory through the First and Second World Wars. It was severely damaged

during the Second World War by the Nazis, when an ammunition storage dump inside the castle exploded.

On 10 January 2009, the castle suffered severe damage from an accidental fire due to electrical wires short-circuiting.

The Royal Logis, which contains old tomes and administrative offices, was the most heavily damaged part of the

chateau, resulting in 400 square metres (4,300 sq ft) of the roof being completely burnt. The Tapestries of the

Apocalypse were not damaged. Total damages have been estimated at 2 million Euros. The City of Angers now

owns the massive, austere castle, and it has been converted to a museum housing the oldest and largest collection

of medieval tapestries in the world. It maintains the 14th-century “Apocalypse Tapestry” as one of its priceless

treasures. As a tribute to its fortitude, the castle has never been taken by any invading force in history.

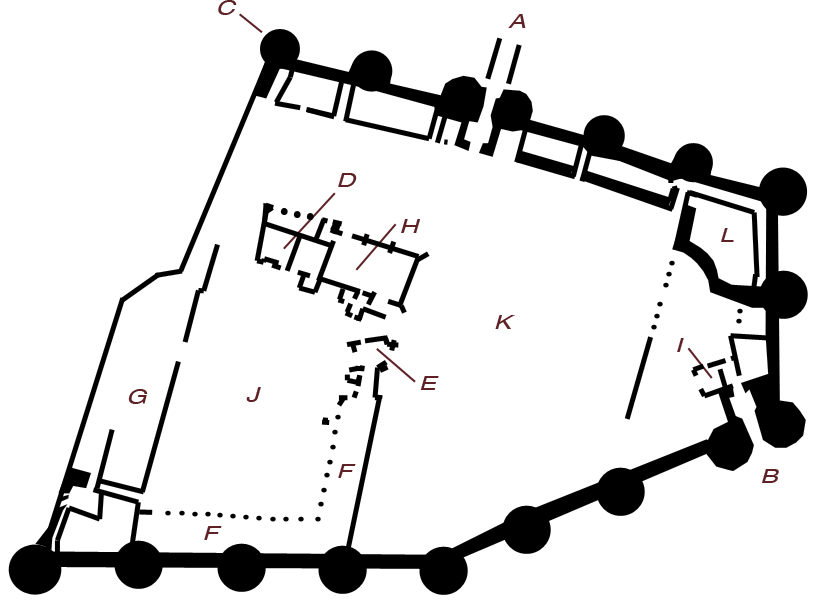

The outer wall is 3 metres (9.8 ft) thick, extends for about 660 m (2,170 ft) and is protected by seventeen massive

towers. Each of the perimeter towers measures 18 m (59 ft) in diameter. The château covers an area of 20,000

square metres (220,000 sq ft). Two pairs of towers form the city and landward entrances of the château. Each of

the towers was once 40 metres (130 ft) in height, but they were later cut down for the use of artillery pieces. The

Tour du Moulin is the only tower which conserves the original elevation.

(Delbos, Claire (2010), La France fortifiée: Châteaux, citadelles et forteresses (in French), Petit Futé)

(Chatsam Photo)

Château d’Angers.

(Chatsam Photo)

Château d’Angers, entrance.

(Denis Jarvis Photo)

Château d’Angers.

Ground plan of Château d’Angers: A: gate to the medieval town; B: south gate; C: Tour de moulin; D: royal

lodgings; E: chatelet (a type of gatehouse); F: gallery of the Apocalypse Tapestry; G: great hall; H: chapel; I:

governor’s lodgings; J: inner court; K: gardens; L: terraced gardens.

(Kauczuk Photo)

Château d’Angers keep.

(Nataloche Photo)

Château d’Angers.

(Kimon Berlin Photo)

The Apocalypse Tapestry at Château d’Angers.

(Wrtalya Photo)

Château du Haut-Kœnigsbourg is a medieval castle located in the commune of Orschwiller in the Bas-Rhin

départment of Alsace. It is located in the Vosges mountains just west of Sélestat, situated in a strategic area on a

rocky spur overlooking the Upper Rhine Plain. It was used by successive powers from the Middle Ages until the

Thirty Years’ War, when it was abandoned. From 1900 to 1908 it was rebuilt at the behest of the German Kaiser

Wilhelm II. Today it is a major tourist site, attracting more than 500,000 visitors a year.

The Buntsandstein cliff was first mentioned as Stofenberk (Staufenberg) in a 774 deed issued by the Frankish

king Charlemagne. Mentioned again in 854, it was at that time a possession of the French Basilica of St. Denis,

and the site of a monastery. It is not known when the first castle was built on this site, but a Burg Staufen (Castrum

Estufin) is documented in 1147, when the monks complained to King Louis VII of France about its unlawful

construction by the Hohenstaufen Duke Frederick of Swabia. Frederick’s younger brother Conrad III, had been

elected King of the Romans in 1138. He was succeeded by Frederick’s son Frederick Barbarossa in 1152, and by

1192 the castle was called Kinzburg (Königsburg, “King’s Castle”).

In the early thirteenth century, the fortification passed from the Hohenstaufen family to the dukes of Lorraine,

who entrusted it to the local Rathsamhausen knightly family and the Lords of Hohenstein, who held the castle

until the fifteenth century. As the Hohensteins allowed some robber barons to use the castle as a hideout, and

their behaviour began to exasperate the neighbouring rulers, in 1454 it was occupied by Elector Palatine Frederick I.

In 1462, the castle was set ablaze by the unified forces of the cities of Colmar, Strasbourg and Basel.

In 1479, the Habsburg Emperor Frederick III granted the castle ruins in fief to the Counts of Thierstein, who

rebuilt them with a defensive system suited to the new artillery of the time. When in 1517 the last Thierstein died,

the castle became a reverted fief and again came into the possession of the Habsburg emperor of the day,

Maximilian I. In 1633, during the Thirty Years’ War, in which Catholics forces fought Protestants, the Imperial

castle was besieged by Protestant Swedish forces. After a 52-day siege, the castle was burned and looted by the

Swedish troops. For several hundred years it was left unused, and the ruins became overgrown by the forest.

Various romantic poets and artists were inspired by the castle during this time.

The ruins had been listed as a “monument historique” of the Second French Empire since 1862 and were purchased

by the township of Sélestat (or Schlettstadt) three years later. After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 to 1871, the

region was incorporated into the German Imperial Territory of Alsace-Lorraine, and in 1899 the citizens granted

what was left of the castle to the German Emperor Wilhelm II. Wilhelm wished to create a castle lauding the

qualities of Alsace in the Middle Ages and more generally of German civilization stretching from Hohkönigsburg

in the west to (likewise restored) Marienburg Castle in the east. He also hoped the restoration would reinforce the

bond of Alsatians with Germany, as they had only recently been incorporated into the newly established German

Empire. The management of the restoration of the fortifications was entrusted to the architect Bodo Ebhart, a

proven expert on the reconstruction of medieval castles. Work proceeded from 1900 to 1908. On 13 May 1908,

the restored Hohkönigsburg was inaugurated in the presence of the Emperor. In an elaborate re-enactment c

eremony, a historic cortege entered the castle, under a torrential downpour.

Ebhart’s aim was to rebuild it, as near as possible, to the way it was on the eve of the Thirty Years’ War. He relied

heavily on historical accounts but, occasionally lacking information, he had to improvise some parts of the

stronghold. For example, the Keep tower is now reckoned to be about 14 metres too tall. Wilhelm II, who

regularly visited the construction site via a specially built train station in nearby Saint-Hippolyte, also encouraged

certain modifications that emphasised a Romantic nostalgia for Germanic civilization. For example, the main

dining hall has a higher roof than it did at the time, and links between the Hohenzollern family and the Habsburg

rulers of the Holy Roman Empire are emphasized. The Emperor wanted to legitimise the House of Hohenzollern

at the head of the Second Empire, and to assure himself as worthy heir of the Hohenstaufens and the Habsburgs.

After the end of the First World War, the French state confiscated the castle in accordance with the 1919 Treaty of

Versailles. It has been listed since 1862 and classified since 1993 as a “monument historique”, by the French

Ministry of Culture. In 2007, ownership was transferred to the Bas-Rhin département.Today, it is one of the most

famous tourist attractions in the region. Bodo Ebhardt restored the castle following a close study of the remaining

walls, archives and other fortified castles built at the same period.

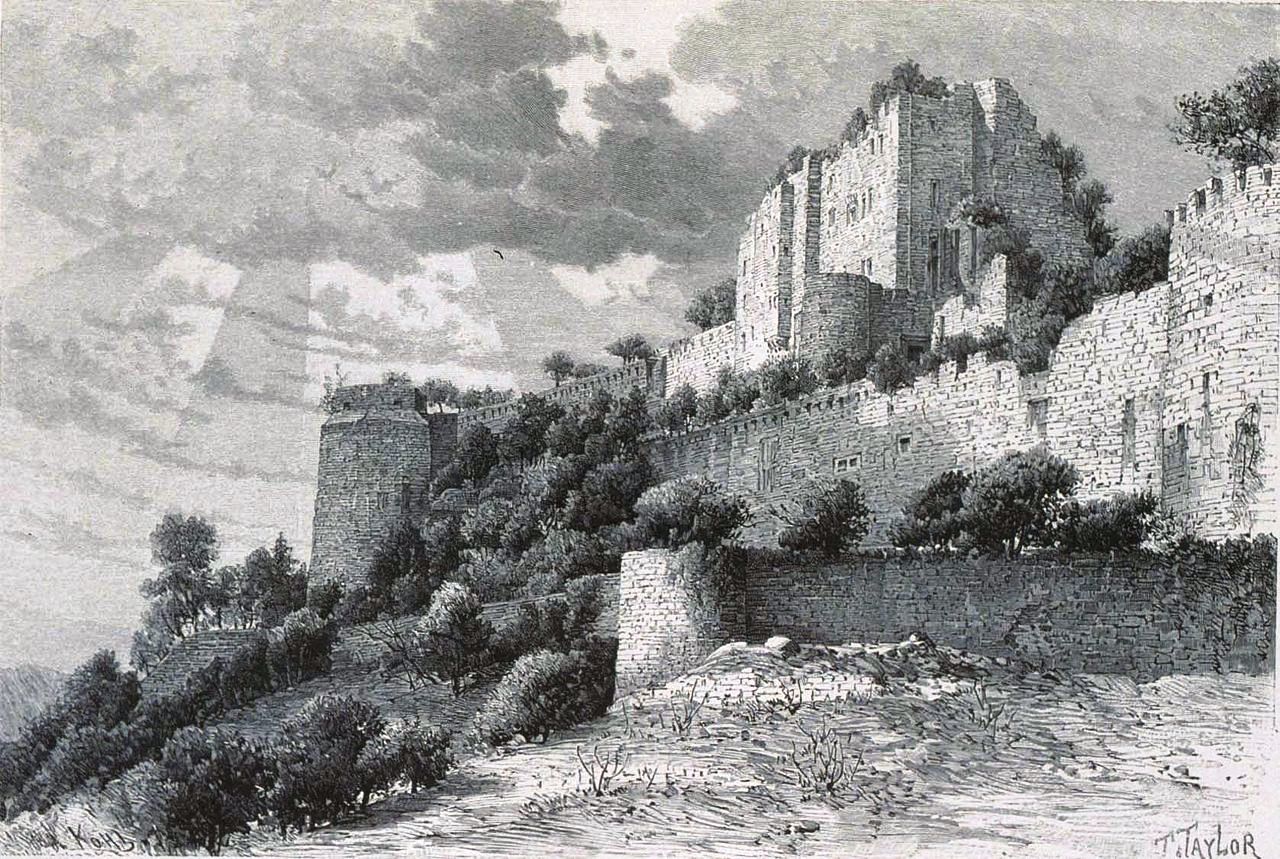

Engraving of Château du Haut-Kœnigsbourg ruins, 1889, by T. Taylor.

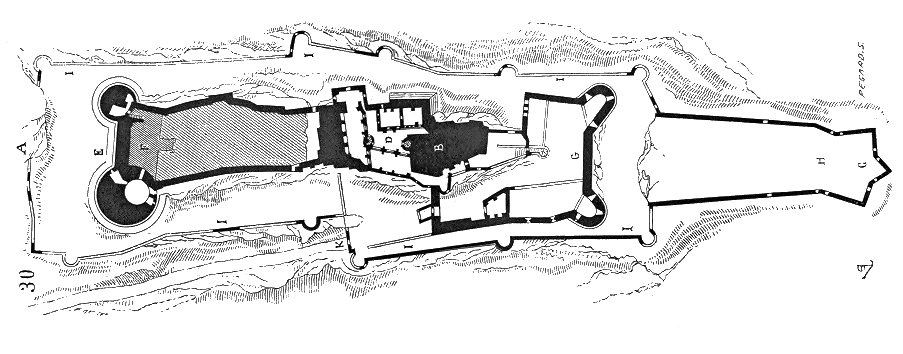

Plan view of Château du Haut-Kœnigsbourg.

(Gzen92 Photo)

Château du Haut-Kœnigsbourg, view from the village of Orschwiller.

(Meffo Photo)

Château du Haut-Kœnigsbourg, main entrance.

(Gregorini Demetrio Photo)

Château du Haut-Kœnigsbourg, main entrance.

(Zairon Photo)

Reliefs over the top of the main entrance to the Château du Haut-Kœnigsbourg.

(Fr Antunes Photo)

Château du Haut-Kœnigsbourg, view looking East.

(Michael Schmalenstroer Photo)

Château du Haut-Kœnigsbourg, Grand Bastion.

(Bernard Chenal Photo)

Château du Haut-Kœnigsbourg, view from the village of Orschwiller.

(Alsace Destination Tourisme, Aerial Photo)

Château fort de Fleckenstein is a ruined castle in the commune of Lembach, in the Bas-Rhin département of

France. This fortress, built in the shape of 52 m long boat, stands on a dramatic rock face and has a long history.

The castle was built on a sandstone summit in the Middle Ages. An ingenious system for collecting rainwater fed

a cistern and a hoist allowed water and other loads to be moved to the upper floors.

A castle is known to have existed on the site in 1165. It is named after the Fleckenstein family, owners until 1720

when it passed to the Vitzthum d’Egersberg family. The family had had a lordship that consisted of four separate

small territories in the Bas-Rhin département. In 1807, it passed to J.-L. Apffel and in 1812 to General Harty,

baron of Pierrebourg (French word for Fleckenstein: stone town). In 1919, it became the property of the French state.

The rock and the castle have been modified and modernised many times. Of the Romanesque castle, remains

include steps cut into the length of the rock, troglodyte rooms and a cistern. The lower part of the well tower

dates from the 13th or 14th century, the rest from the 15th and 16th. The inner door in the lower courtyard carries

the faded inscription 1407 (or 1423); the outer door 1429 (or 1428). The stairwell tower is decorated with the

arms of Friedrich von Fleckenstein (died 1559) and those of his second wife, Catherine von Cronberg (married 1537).

The 16th-century castle, modernised between 1541 and 1570, was shared between the two branches of the

Fleckenstein family. Documents from the 16th century describe the castle and a watercolour copy of a 1562 tapestry

illustrated its appearance in this period. Towards the end of the 17th-century Fleckenstein was captured twice by

French troops. In 1674 the capture was achieved by forces under Marshall Vauban, who encountered no resistance

from the defenders. The castle was nevertheless completely destroyed in 1689 by General Melac. Major restoration

work was carried out after 1870, around 1908 and again since 1958.

The castle is located between Lembach to the south and Hirschtal to the north, only about 200 meters to the

southeast of the present French frontier with Germany, at a height of about 370 meters above mean sea level.

The nearest more substantial town is Wissembourg, approximately 20 km / 12 miles to the east. The castle, is

accessible by road or via (well established) hiking trails. (Ministère français de la Culture. Château fort de Fleckenstein)

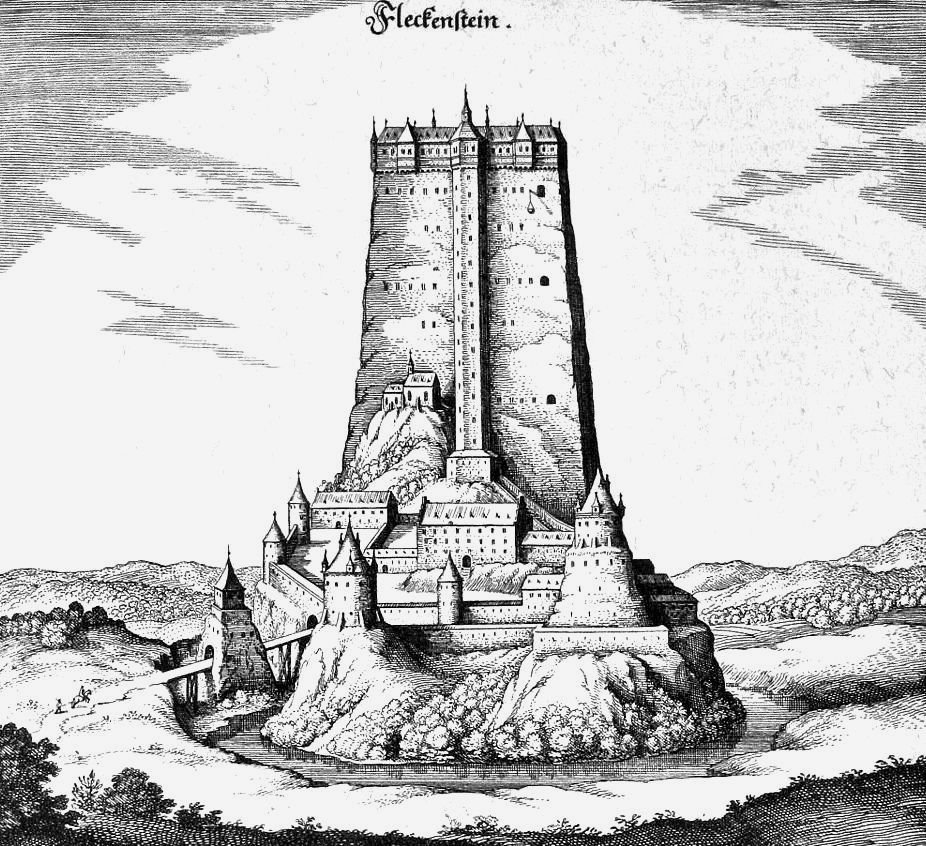

(Merian)

Château fort de Fleckenstein, Matthaus Merian illustration, c1663.

(Made in Alsace Photo)

Château fort de Fleckenstein, view from Hohenburg castle.

(Rob124 Photo)

Château fort de Fleckenstein.

(Pinterest Photo)

Château fort de Fleckenstein, aerial view.

(Stardsen Photo)

Château de Coucy is a French castle in the commune of Coucy-le-Château-Affrique, in Picardy, built in the 13th

century and renovated by Eugè Viollet-le-Duc in the 19th century. During its heyday, it was famous for the size

of its central tower and the pride of its lords, who adopted the staunchly independent rhyme: roi ne suis, ne prince

ne duc ne comte aussi; Je suis le sire de Coucy (“I am not king, nor prince nor duke nor count; I am the Lord of Coucy”).

The castle was constructed in the 1220s by Enguerrand III, Lord of Coucy. The castle proper occupies the tip of a

bluff or falaise. It forms an irregular trapezoid of 92 x 35 x 50 x 80 m. At the four corners are cylindrical towers

20 m in diameter (originally 40 m in height). Between two towers on the line of approach was the massive donjon

(keep). The donjon was the largest in Europe, measuring 35 meters wide and 55 meters tall. The smaller towers

surrounding the court were as big as the donjons being built at that time by the French monarchy. The rest of the

bluff is covered by the lower court of the castle, and the small town.

Coucy was occupied in September 1914 by German troops during the First World War. It became a military

outpost and was frequented by German dignitaries, including Emperor Wilhelm II. In April 1917, the German

army dynamited the keep and the four towers using 28 tons of explosives to prevent their use by enemy artillery

spotters as the Germans fell back in the region.

The demolition was done on order of General Erich Ludendortt, destroying the keep and the 4 towers. The

destruction caused so much public outrage that in April 1917 the ruins were declared “a memorial to barbarity”. War reparations were used to clear the towers and to consolidate the walls but the ruins of the keep were left in place.

Château de Coucy has been listed as a monument historique by the French Ministry of Culture since 1862.

(Laurent, Jean-Marc. Le château féodal de Coucy. La Vague verte, 2001)

(Shep Photo)

Model of Château de Coucy.

Aerial view of Château de Coucy before its destruction in 1917.

(Siaux Romuald Photo)

Château de Coucy.

(Siaux Romuald Photo)

Château de Coucy.

(Szeder László Photo)

Château de Coucy.

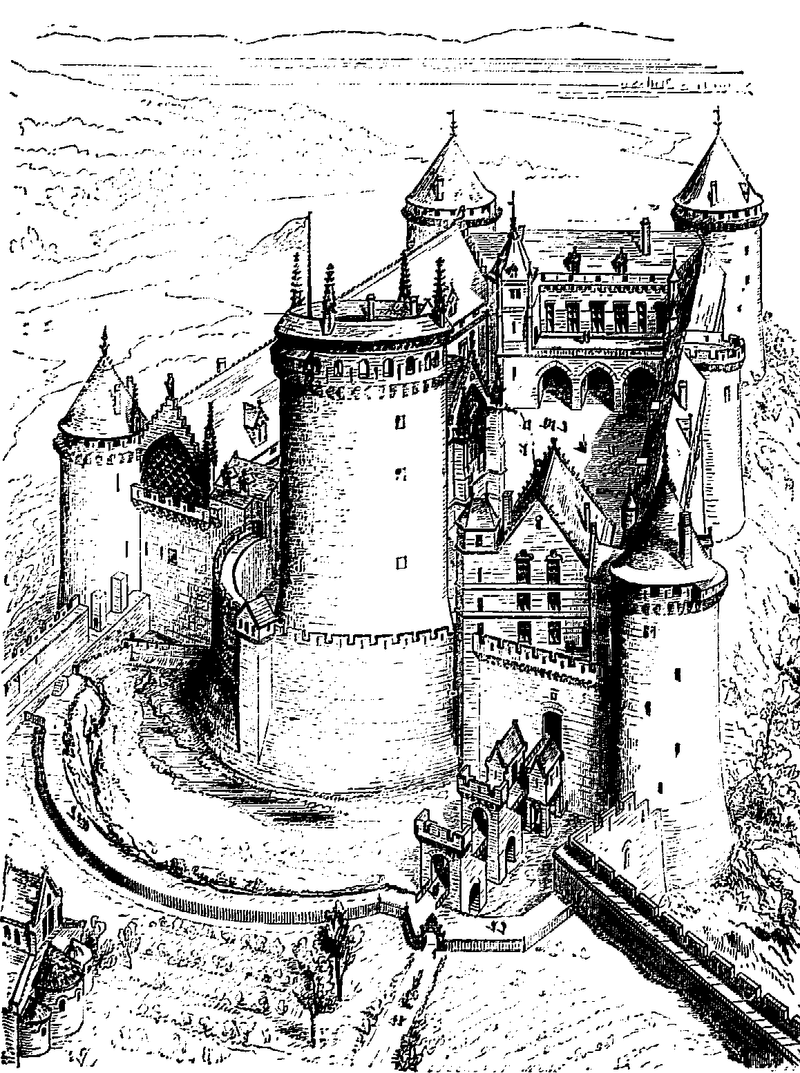

Château de Coucy illustration by Viollet-le-Duc

(Rolf Kranz Photo)

Château de Coucy.

If you would like to learn more about castles and sieges have a look here:

It has been said that the taking of a fortress depends primarily on the making of a good plan to take it, and the

proper implementation and application of the resources to make the plan work. Long before a fortress has been

besieged and conquered, it has to have been outthought before it can be outfought. This book outlines some of the

more successfully thought out sieges, and demonstrates why it is that no fortress is impregnable.

A siege can be described as an assault on an opposing force attempting to defend itself from behind a position of

some strength. Whenever the pendulum of technology swings against the “status quo,” the defenders of a fortification

have usually been compelled to surrender. We must stay ahead of the pendulum, and not be out-thought long before

we are out-fought, for, as it will be shown in this book, “no fortress is impregnable.”

Order book, soft cover or hard cover: http://bookstore.iuniverse.com/Products/SKU-000018310/Siegecraft–No-Fortress-Impregnable.aspx

Order in Canada: paperback http://www.chapters.indigo.ca/books/Siegecraft-No-Fortress-Impregnable-Harold-A-Skaarup/9780595275212-item.html?ikwid=harold+skaarup&ikwsec=Books