ROLL CALL NEWSLETTER OF THE FRIENDS OF THE NEW BRUNSWICK MILITARY HISTORY MUSEUM/

AMIS/AMIES DE MUSEÉ D’HISTOIRE MILITAIRE DU NOUVEAU-BRUNSWICK

Volume 8, Issue 3 Fall 2022

Remembering the Llandovery Castle

by Brent Wilson

The recent publication of Dianne Kelly’s book, Asleep in the Deep: Nursing Sister Anna Stamers and the First World War (Fredericton: Goose Lane Editions and the Gregg Centre, 2021) renewed interest in New Brunswick’s connection with the in famous sinking of the Canadian Hospital Ship Llandovery Castle in June1918 by a German submarine. In addition to N.S. Stamers who came from Saint John, twelve other New Brunswickers were lost during the attack, including Privates Harry Harrison (#536276), Edward M. Macpherson (#536277), and Walter B. Sacre (#536477) from the mall town of Marysville.

These men had much in common. All were young when they enlisted: Harrison and Sacre were both 21, while Macpherson was only 19 years old. All listed their occupation as laborer. Perhaps the biggest difference was their place of birth. Harrison was born in Marysville and Macpherson was from nearby Fredericton (although his mother, Charlotte, lived in Marysville), whereas Sacre was born in Swansea, Wales. He immigrated to Canada and lived in Marysville along with his wife, Laura, and parents, Annie and Walter, who resided at 41 Morrison Street.

Between August 1916 and March 1917, they enlisted in No. 16 Canadian Field Ambulance of the Canadian Army Medical Corps, which was organized in Saint John.

On 28 March 1917, they sailed from Halifax on board the troopship Saxonia, along with several other men from Marysville, including Corporal Walter Sacre, Sr., Walter’s father. They arrived in England on 7 April. Later, Harrison, Macpherson, and Sacre became members of the medical personnel serving on board the Llandovery Castle. On 27 June 1918, the ship was sailing from Halifax to Liverpool to pick up casualties when it was torpedoed and sunk by a German U-Boat (submarine) about 100 miles off the southern coast of Ireland. Of those serving on board the ship 234 perished and only 24 survived, making it the worst Canadian naval disaster of the First World War. All three privates from Marysville were lost at sea. Making the event even worse, the submarine had not only fired on a clearly marked hospital ship, a violation of international law, but afterwards the Germans rammed lifeboats and fired on survivors in the water.

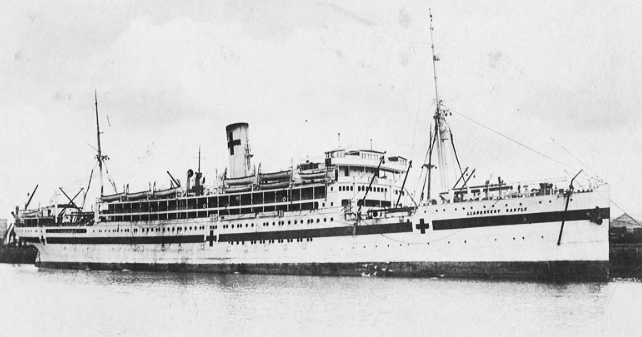

(Photo courtesy of Harold Wright)

His Majesty’s Hospital Ship Llandovery Castle with hospital markings. Under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Howard MacDonald of Nova Scotia, HMHS Llandovery Castle was torpedoed and sunk by the German submarine U-86 on 27 June 1918. Firing at a hospital ship was against international law and standing orders of the Imperial German Navy. The captain of U-86, Helmut Brümmer-Patzig, sought to destroy the evidence of torpedoing the ship. When the crew, including nurses, took to the lifeboats, U-86 surfaced, ran down all but one of the lifeboats and machine-gunned many of the survivors. Only 24 people in one lifeboat survived. They were rescued shortly afterwards by the destroyer HMS Lysander and testified as to what had happened.

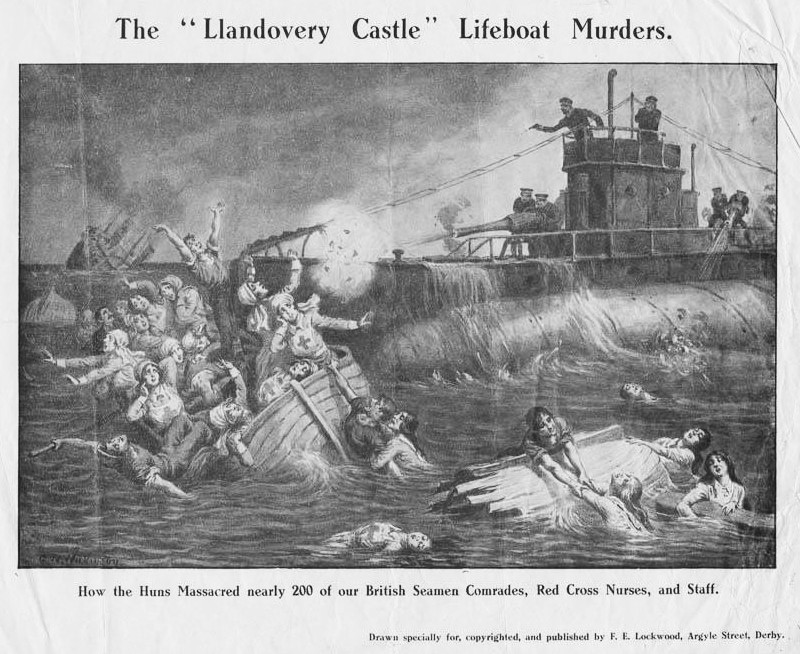

HMHS Llandovery Castle, print by G.W. Wilkinson, 27 June 1918.

Needless to say, this incident provoked widespread outrage in Canada and internationally. The Canadian and British governments made it the focus of a concerted propaganda campaign. The St. John Standard newspaper referred to the German submariners as “Hun pirates.” One can only imagine how the families felt when they received notification of the loss of their loved ones amid the anger that surrounded the event. The Standard reported that “the families of the boys…are prostrated over the news of the sinking.”

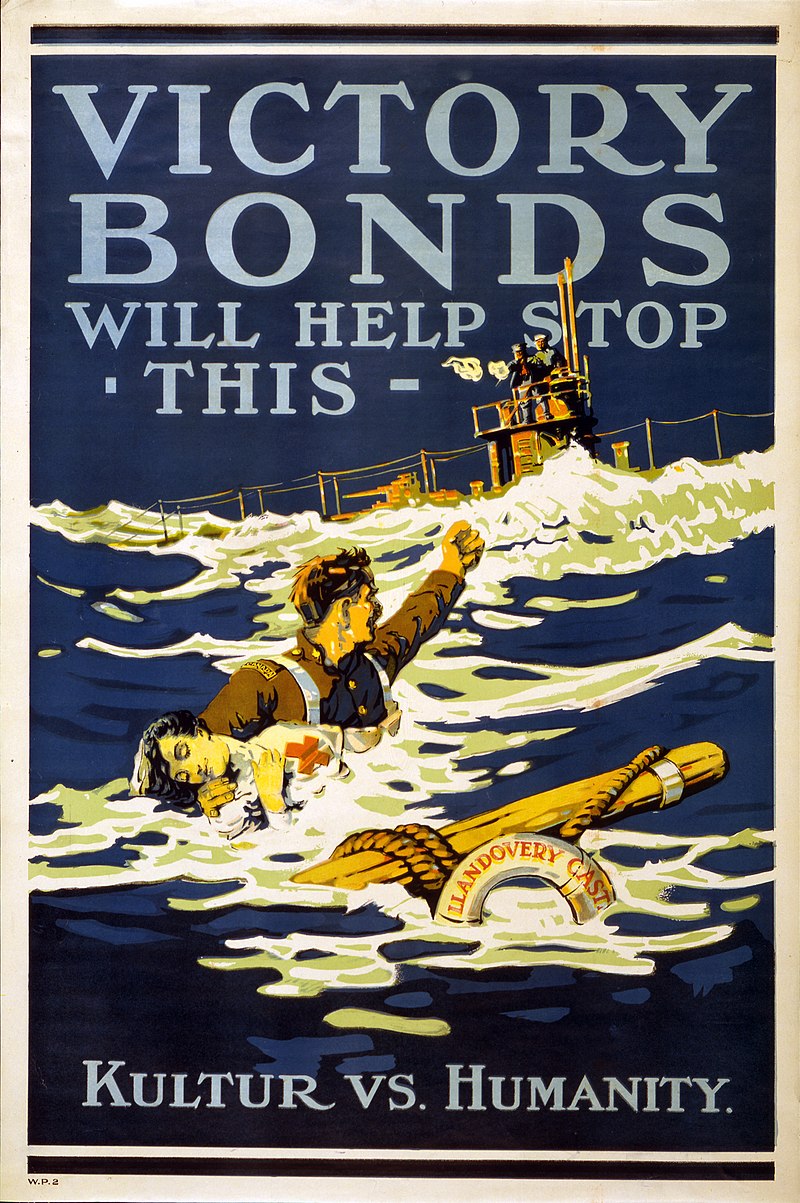

(Canadian War Museum, 19850475-034)

Canadian war bonds poster depicting the German submarine U-86 firing on Canadian survivors from the Llandovery Castle.

In 1921, the captain and two officers of the U-Boat were put on trial in Germany for war crimes. However, the captain escaped the country and the other officers were acquitted on appeal on the grounds that the captain was solely responsible for the incident. It is doubtful Marysville families would have felt like justice had been served.

(Hantsheroes Photo)

Nursing casualties are listed on the Halifax Memorial and the names of Privates Harrison, Macpherson, and Sacre appear on the Halifax Memorial to the Missing in that city’s Point Pleasant Park. This is the official memorial for all Canadian military personnel who were lost at sea during both world wars. Their names also appear on the Marysville Great War Cenotaph in Veterans Memorial Park on Canada Street, which was erected in 1925 on land donated by Canadian Cottons, the owners of the nearby cotton mill.

Brent Wilson is the Director of the New Brunswick Military Heritage Project at the Gregg Centre at the University of New Brunswick and Editor of Roll Call.

“There I Was”

by Harold Skaarup

How fortunate we are! One of the most remarkable things about having served in the Canadian Forces is that most of us have had an extraordinary number of interesting experiences while wearing the uniform. Many of us are lucky enough to have lived to tell the tales, but I find that most do not share much of what they have seen and learned. Canadians need to know how fortunate they are to have been protected from the kind of threat that the people of Ukraine are experiencing even now.

(DND Photo)

I am often asked to speak to school groups via the Memory Project, and I like to ask the kids to imagine what it was like to have the air raid siren go off and to have your teachers tell you to get under your desk, or to hustle to the school basement in case of a bomb threat. I have them do that in the classroom, and then speak to them for a few moments, while they are sitting under their desks. Although they are smiling, I tell them that in 1962 the teachers I had at RCAF Station 3 (Fighter) Wing in Zweibrucken, Germany were not.

(Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-B0628-0015-035 / Heinz Junge)

At that time, Russia’s Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev, the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, took off his shoe and banged it on the podium in the United Nations Headquarters in New York and shouted, “we will bury you.” The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 was a 35-day confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union, which escalated into an international crisis when American deployment of missiles in Italy and Turkey were matched by Soviet deployment of similar ballistic missiles in Cuba. Despite the short time frame, the Cuban Missile Crisis remains a defining moment in nuclear war preparation. The confrontation was likely the closest the Cold War came to escalating into a full-scale nuclear war.

As the children are sitting under their desks, I ask them to remember this, and the next time they see an old veteran with only one or two medals, to take the time to say thank you and to shake their hand. Because they stood prepared and ready to stop a war, we didn’t have a war, and they as students never had to get under their desks for real. It can be hard to imagine just how fortunate we have been and are to this day.

I have given a number of tours to school groups, seniors, and serving soldiers at the NBMHM, and have been invited to speak to Grade 12 classes at Fredericton High School. Some schools really do want to hear our stories. Yes, some things we have experienced can induce trauma. On the other hand, we all have a “there I was, no sh*t, and a weaker man wouldn’t have survived!” story to tell. I saw these two Military Freefall Parachutists (MFP) get their rucksacks stuck together on exit, just as I took the photo. Although they were in serious trouble for a few moments, they managed to separate OK. I am sure, however, that both of them had a “there I was” story to tell afterward. I am equally sure many of our readers have a “there I was” story of their own to tell, and we would like to hear them!

If we don’t tell our stories, who will? Canadians need to knowhow fortunate we are.

(Harold Skaarup Photo)

Lockheed C-130 Hercules dropping Military Freefall jumpers over Edmonton, Alberta during the winter of 1979-80. Two of the jumpers the author photographed here managed to get their rucksacks hooked together on exit. They managed to get disentangled fairly quickly, but it did make the jump a bit more interesting for the participants.

The St. John River Flotilla During the War of 1812

by Gary Campbell in collaboration with Robert Dallison

As the threat of war with the United States increased during 1811, the British were considering ways to defend New Brunswick. There were two vital areas to protect. One was the harbour of Saint John. This was the port from where the long, clear white pine logs were shipped to England to be made into the masts and spars that were so vital to the Royal Navy. The other was the Grand Communications Route that ran up the St. John and Madawaska Rivers, across Lake Temiscouata and over the Grand Portage to the St. Lawrence River. This route was the only all-year one that linked London, Halifax, and Quebec City. It was of particular importance during the five or six months each year when the St. Lawrence River was closed to navigation because of ice. The creation of a flotilla to defend the St. John River was part of this planning. In August 1811, Captain Gustavus Nicolls, Royal Engineers in Halifax wrote to Captain James MacLauchlan, Commander Royal Engineers in New Brunswick, to ask how many boats in the river could be made into gunboats in an emergency? The idea was to either use them as bateaux to carry 30 men or to mount an 18-pounder carronade in their bow.

MacLauchlan evaluated the options of purchasing and refitting existing boats or building new ones and recommended buying new ones. While Nicolls was writing on behalf of Lieutenant General Sir John Coape Sherbrooke, the Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia and Commander of the military forces in Nova Scotia command that included New Brunswick, Major General Sir Martin Hunter, the President of the Council in New Brunswick and commander of the provincial militia, was also interested in this idea.

From the correspondence it appears that there were already “garrison bateaux” on the St. John River that were used to transport supplies between Fredericton and the Upper Posts at Presqu’ile and Grand Falls. There was also a gunboat that needed to be replaced. The additional boats would be an expansion of an existing capability.

The United States declared war on 18 June 1812 and British preparations to defend New Brunswick began in earnest. One of the first considerations was improving the defences of Saint John. Nicolls wrote to MacLauchlan on 25 July and provided guidance for the preparations. He was to use the “greatest economy” on any works. In Nicolls’ opinion: “the principal defence to be made in New Brunswick, by an inferior Army [i.e., the British Army, which was deployed primarily in Nova Scotia in this region] must be on the River Saint John and its Banks, and that by means of a superior Flotilla….” The creation of the St. John River Flotilla had apparently become official policy; on 28 July, MacLauchlan sent one of the newly constructed bateau to Major General George Stracey Smyth, Hunter’s successor, for approval. Having received feedback from Smyth, MacLauchlan proceed with the construction programme. On 3 August, he reported that one of the contractors “will have completed their ten boats on Saturday.” Some of the boats were being built at a works near Fort Frederick at Saint John. These consisted of eight bateaux and one large boat equipped to carry two 24-pounder guns. Not all was going well, however, as another contractor was experiencing delays in the construction of his five boats. Later in the month, MacLauchlan reported that there were ten boats at Fredericton. Five carried a 6-pounder cannon, two had a 3-pounder cannon, one was fitted to carry 30 troops and the details of the other two were not mentioned. It is possible that they were not armed due to a shortage of guns.

At the end of July, Smyth had indicated that there were only four guns in the province that were “fit for the Batteaux.” By the end of September, MacLauchlan submitted another report that stated 15 bateaux were completed and were mounted with field pieces. The calibre of these guns was not given. Two wood-boats were decked and mounted with a 24-pounder carronade. One had been mounted with three 24-pounder carronades (two in the bow and one on the stern) on a trial basis and had been found to be able to withstand the shock of firing. However, Smyth had decided that “one gun [was] quite sufficient.” In the absence of any immediate threat, the boats were being used to carry provisions from Saint John to Fredericton. This appears to have been the extent of the Saint John River Flotilla. This was confirmed in a report dated 1 January 1813 that states “2 of the Riverwood boats mounting 2×24 pdr carronades and 15 bateaux have been fitted with ordnance by order of the Lieutenant General Commanding and paid for out of the contingency of the army.” Apparently, Smyth had reconsidered the armament on the gunboats.

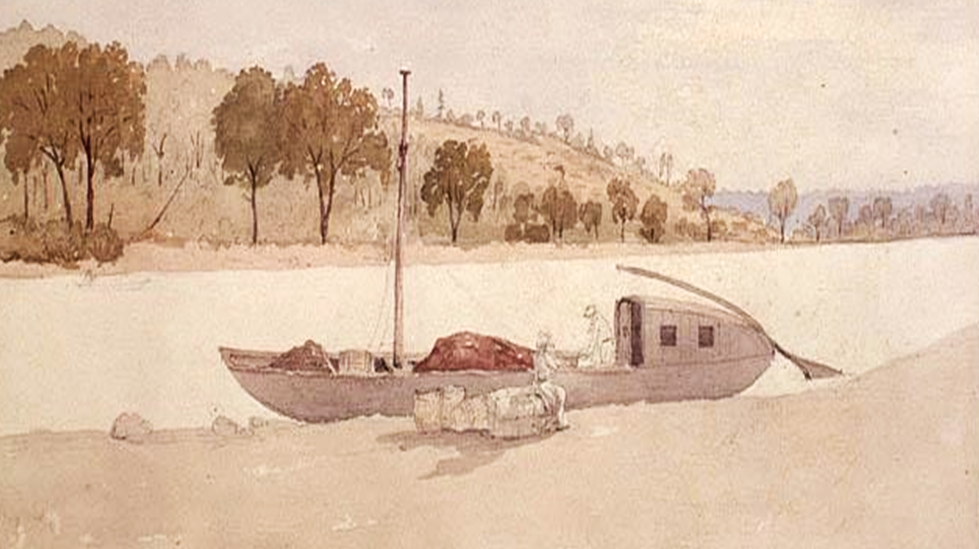

River Bateau.

There were two types of boats in the flotilla. The majority were described as bateaux, a flat-bottomed boat that was capable of carrying troops and supplies, and mounting a small gun in the bow. They were about 38 feet long. The other type was a larger, wood-boat. These were used as general- purpose cargo boats along the St. John River. Their name comes from them being used to carry firewood. They were capable of carrying a load of 40 tons or 28 cords of wood. The Brunswick Lion at King’s Landing is are construction of one of these boats. They were a bit longer at about 42 feet and the open holds could be decked over. Larger guns, such as carronades, could be mounted on their decks. The cost of building a bateau was £35 while the cost of a wood-boat was not given. Both types of boats were equipped with sails and the bateaux had a sweep oar on the stern for steering. It appears that they were crewed, at least in part, by soldiers stationed in New Brunswick. W. Austin Squires in The104th Regiment of Foot (The New New Brunswick Regiment),1803-1817 (Fredericton, N.B.: Brunswick Press, 1962) mentions “Private Philip Callaghan [of the 104th] was in charge of a gunboat” and writes that “They [the New Brunswick Fencibles] also manned several armed gunboats on the St. John River.” George F.G. Stanley states in “The New Brunswick Fencibles” (Canadian Defence Quarterly, vol. XVI, No. 1,October, 1938) that one of the corporals in the New Brunswick Fencibles“ was a pilot on a gun boat on theSt. John river”.

It appears that the flotilla was designed to perform a number of tasks. Based on Nicolls’ report of 14 November 1812 in which he made recommendations to Sherbrooke about the defence of New Brunswick, the flotilla was to command the St. John River below Fredericton. He observed “that it must be attended with much hazard anddifficulty, for an enemy to establish himself on its [the St. John River]Banks, or to keep up a communication across it below Fredericton while we have a superior Flotilla on the River….”Although it did not occur, the threat of an American attack was not an empty one. On 16 September 1812, Sherbrooke advised Earl Bathurst, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, that the Governor of Massachusetts had declined a request from Washington to mobilize the state militia. However, the Federal government was raising three regiments of 1,000 men each there and it was anticipated that they might be used in operations against New Brunswick.

Both MacLauchlan and Nicolls saw the need to establish a fortified depot around Grand Lake or Lake Washademoak. If attacked, the gunboats would be used to help defend it or any other point that needed to be quickly reinforced. The first official function of the flotilla was to participate in the celebrations held at Fredericton on 10 September 1812 marking the victory at Detroit. Because the Americans did not attack New Brunswick or threaten the St. John River, the flotilla probably spent most of the war transporting troops and supplies along the river. The records show that boats from the flotilla were used to move a detachment of the 104th to Saint John in April 1813 and to carry a relief party to the Upper Posts the next month.

The last entry in the Royal Engineer papers relating to the flotilla is dated 22 October 1814 and it states that some bateaux were being sent to Saint John for repairs. Given the traditional post-war need for economy, some of the boats were likely sold off. However, it appears that others were retained in service, as there was still a need for military transport along the lower St. John River, as well as to the garrisons at the Upper Posts.

Two years later, a new requirement for the bateaux arose when it became necessary to transport the soldiers of several disbanded regiments, their families, and supplies to the military settlement being established between the military posts at Presqu’ile and Grand Falls. In March 1816, Captain MacLauchlan was directed to have five boats at Fredericton repaired and readied for use in the spring to transport provisions from Saint John to Grand Falls for use by military settlers from the 10th Royal Veterans Battalion. Ernest Clarke in The Weary, The Famished and The Cold: Military Settlement, Upper St. John River, 1814-1821 (Carleton County Historical Society, Woodstock, N.B., 1981)indicates that soldiers were used to operate these boats. If some of the vessels from the St. John River Flotilla were employed in this service, they probably were among those that Peter Fisher found abandoned along the shore at Presqu’ile when he visited the area circa 1825. About fifty years ago, a small, approximately 3-pounder iron cannon was found along the banks of the St. John River not far from the site of the Presqu’ile military post. It is possible that this was one of the guns that were used to arm the bateaux.

The establishment of the St. John River Flotilla is a unique event in the military and naval history of New Brunswick. It provided a highly mobile capability to bring additional firepower and troop reinforcements to bear on any area along the lower St. John River that was under enemy threat. When not engaged in combat operations, it was used to transport troops and provisions. It was New Brunswick’s counterpart to the much better-known Provincial Marine and Commissariat Voyageurs that operated along the St. Lawrence River and on the Great Lakes of Canada during the War of 1812. Most importantly, its existence underscored the fact that shallow waters as well as deep ones need to be defended.

(The Brunswick Lion at King’s Landing)

Gary Campbell, PhD, is a retired Canadian Army Logistics officer. He has a special interest in logistics history, especially where it involves transportation.

His articles on this subject have been published in several journals, both in Canada and abroad.

Robert Leonard Dallison attended both the Royal Roads Military College and the Royal Military College of Canada and, following graduation in 1958, was commissioned into the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry. He received a BA (History) from R.M.C. and a BA (History and International Studies) from the University of British Columbia. He served for thirty-five years with the Canadian Army, obtaining the rank of lieutenant-colonel, and ending his career as Chief of Staff of the Combat Arms School at CFB Gagetown. After retiring, he maintained his life-long interest in history and heritage, including serving as the President of Fredericton Heritage Trust and as the New Brunswick representative on the Board of Governors for Heritage Canada. From 1992 to 2002, he was Director of Kings Landing Historical Settlement, a living history site portraying the Loyalist settlement in the St John River Valley of New Brunswick. In 2008, he developed a permanent Loyalist exhibit for the York-Sunbury Museum. Dallison has a particular interest in the Loyalist regiments and the military campaigns of the revolutionary period. In 2003 he published Hope Restored – The American Revolution and the Founding of New Brunswick (Fredericton: Goose Lane, 2003).

Tunic of Regimental Sergeant Major Herbert Endall, 26th Battalion. 2009.008.01, NBMHM.

ROLL CALL

NEWSLETTEROF THE FRIENDS OF THE NEW BRUNSWICK MILITARY HISTORY MUSEUM

AMIS/AMIES DE MUSEÉ D’HISTOIRE MILITAIRE DU NOUVEAU-BRUNSWICK

Volume 8, Issue 1 Spring 2022

Roll Call is published four times a year: Spring, Summer, Fall, and Winter.

Submissions or comments can be sent to the Editor, Brent Wilson, at: jwilson@unb.ca.

For details on joining the Friends, please contact the Museum at 506-422-1304or email us at: friendsnbmhm@gmail.com.

Friends of the New Brunswick Military History Museum

Executive:

President-Brian MacDonald

Vice-President- Harold Skaarup

Secretary- Doug Hall

Treasurer-Randall Haslett

Directors-

Paul Belliveau

Gary Campbell

Robert Dallison

Brent Wilson

Harold Wright

The Revitalization of the NBMHM

by Captain David C. Hughes

I feel extremely lucky to be writing this article for the newsletter as the current Director/Museum Officer of the New Brunswick Military History Museum (NBMHM). For me this is a dream job, and I am excited to be leading the charge on the revitalization of the museum.

In April 2021, the commander of 5 CDSG, Colonel Dwayne Parsons, asked me to take over the museum as he knew that the previous Executive Director would be resigning. I said yes, of course, and immediately started work on bringing the NBMHM back to its former glory after many years of neglect. I am fortunate to have the support and advice of the executive of the Friends of the NBMHM. As we work together to make the NBMHM the true Centre of Excellence for all things related to New Brunswick military history, we are setting ambitious goals, creating new partnerships and opportunities, and bringing the rich military history of our province and its people to an even bigger audience every day.

Some aspects of the revitalization of the museum have already begun. In 2021, we developed the Class Visits Program, which will allow a teacher to either bring their students into the museum or for museum staff to “beam in” to the classroom via MS Teams. Participants from grade levels K to 12 will receive grade level appropriate learning from costumed interpreters that covers a variety of topics relating to the military history of the province over the centuries. The program was developed using the current New Brunswick Schools Curriculum Outcomes as a guide. So far, Anglophone School District West is on board. The COVID situation and current staffing shortages, however, forced us to put the program on hold until the new school year and we hope to begin delivering it to students starting in September 2022. Aswe move forward the goal is to make this program available to all school districts in the province, and to have it available in both English and French.

The weapons vault at the NBMHM was bursting at the seams with our vast collection of weapons. Rather than have them locked up and out of sight we are developing many new weapons displays at the museum where visitors can see an example of all the small arms used by the military in New Brunswick from the 1700’s to the present day. We also have a great collection of the weapons of our allies and adversaries.

We are developing Army, Navy, and Air Force “Profiles” galleries that will tell the stories of individual New Brunswickers who have served in those three arms of service. Also, we are creating The Royal New Brunswick Regiment Gallery. The story of the RNBR goes back over 250 years and touches almost every aspect of New Brunswick’s military history.

Colour of the 71st York Regiment which is perpetuated by the RNBR.

This gallery will be a miniature timeline but will be specific to the antecedent regiments of the RNBR. It will provide a proper home to the RNBR History Collection which was accessioned to the NBMHM by the Regiment a couple of years ago.

The “Feature Exhibit” plan has been put in place and has been very successful so far. Each Feature Exhibit highlights a particular aspect of the military history of the province. The exhibit is displayed in our front foyer for approximately a month at a time. We continue to receive donations and loans of artifacts from other museums, veterans’ groups, and private collectors. We are very grateful for all these items, and they are helping us to present fantastic stories of New Brunswick’s military history in an exciting and meaningful way.

Part of the overall plan for the museum was to also revitalize our social media presence. Our Facebook page has gone from about 500 page likes to over 2,400 page likes and over 2,500 followers. Posts are going up on the page almost daily and each month we are producing a video on the Feature Exhibit.

In the next few months, we will begin our “spring offensive” on our outdoor vehicle and field gun displays. Many of the monument vehicles and guns need restoration, a coat of paint, and some TLC. We will soon be putting the team together to make this happen so that visitors can stroll the museum grounds, and elsewhere on Base Gagetown, and see fine, properly maintained fighting vehicles, guns, and support vehicles from our history. I could go on and on about what we have going on at the NBMMHM but I will end here and advise the reader to check out our Facebook page at NBMHM-MHMNB, and visit the museum in person. We are currently open 9am to 4pm Monday to Friday and will be expanding our hours into the weekends and holidays starting in the summer.

Captain David C. Hughes, CD, is Executive Director of the New Brunswick Military History Museum. He is a 38-year veteran of the CAF. He and his wife, Geraldine Mazerolle, have two beautiful daughters, Sara, 16, and Emma, 13.

The NBMHM’s Russian T-72 Main Battle Tank

by Harold Skaarup

(Harold Skaarup Photo)

Many of us are watching the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. Both sides are using upgraded versions and variants of the Soviet-designed T-72 main battle tank that entered production in 1970. It was the most common tank deployed by the Soviet Army from the 1970s to the collapse of the Soviet Union. It has been widely exported and is used by more than 40 countries. In the 1970s, four that had been in service with the former East German Army came to CFB Gagetown (now 5 Canadian Division Support Base Gagetown).

The tanks were initially used as Opposition Force (OPFOR) trainers and provided realistic training for our combined arms forces participating in live training on base. Due to international agreements related to the Arms Verification Program, three were eventually turned into targets on the Gagetown ranges and one came to the NBMHM. The Armour School has assisted with keeping the T-72 in a presentable state.

Built in the former Soviet Union, the T-72 has been equipped with laser rangefinders since 1978. It is armed with a125-mm 2A46 series main gun and is capable of firing anti-tank guided missiles, as well as standard main gun ammunition, including High-explosive anti-tank(HEAT) and armour- piercing fin-stabilized discarding sabot (APFSDS) rounds. The125-mm main gun of the T-72 has a mean error of one metre (39 inches)at a range of 1,800 m (2,000yd). Its maximum firing distance is 9,100m (10,000 yd), due to limited positive elevation. The limit of aimed fire is 4,000 m (4,400 yd) (with the gun-launched anti-tank guided missile, which is rarely used outside the former USSR). The T-72’s main gun is fitted with an integral pressure reserve drum, which assists in rapid smoke evacuation from the bore after firing. The 125-mm gun barrel is certified strong enough to ram the tank through forty centimetres of iron-reinforced brick wall, though doing so will negatively affect the gun’s accuracy when subsequently fired.

The museum staff have occasionally opened the T-72 to visitors under close-supervision. This provides troops and visitors the opportunity to experience the interior of the tank and to get the real feel of being inside one. Most people are surprised to discover how compact the interior is, with the driver essentially operating the tank in a horizontal position. In July, 2021, Bob Dallison brought the Garrison Club history enthusiasts to examine the museum’s armoured fighting vehicle (AFV) collection and with the aid of a ladder, many of them took the opportunity to check out the T-72 and other vehicles on display. We will be opening other AFVs in the collection at future events and hope you will join us.

Major (Retired) Harold Skaarup, BFA, MA, CD, served as a Canadian Forces Intelligence Officer, retiring in 2011. He earned his Master’s degree in War Studies through RMC and is the Vice-president of the Friends of the NBMHM (and President of the York Sunbury Historical Society).

New Brunswick and the Trent Affair of 1861

by Gary Campbell

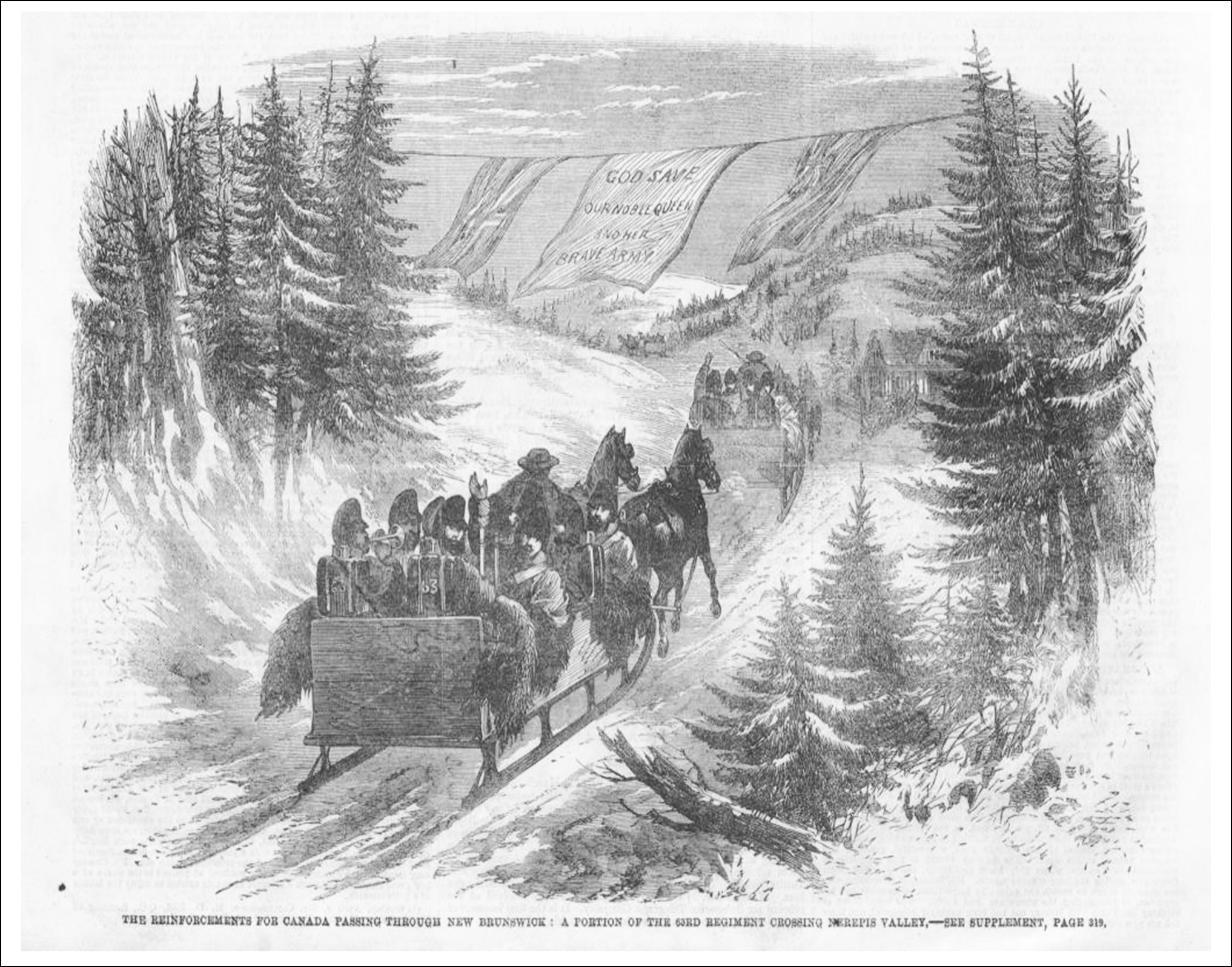

The outbreak of the American Civil War in April 1861 led to rising tensions between Great Britain and the United States. Diplomatic antagonism reached fever pitch in November 1861 after the USS Jacinto, a US Navy warship, illegally intercepted the British mail packet RMS Trent on the high seas and removed two Confederate envoys, one of whom was bound for England. While the American public delighted in the twisting of the lion’s tail, the British public was outraged. War seemed to be the likely outcome. In order to help defend British North America, a large-scale reinforcement was quickly planned. As the St. Lawrence River was closed due to ice, the troops destined for the Canadas would land in Saint John, New Brunswick and move by sleigh over the Grand Communications Route toRiviere du Loup for onwards travel by rail. By the time the deployment was over, 11,500troops had been sent to British North America of which 6,818had passed through New Brunswick to the Canadas.

British reinforcements travelling through New Brunswick in early 1862.

A great deal of planning went into this deployment. The horror of the Crimean winter of 1854/55 was still fresh in British minds. Medical experts, such as Florence Nightingale, and experienced logisticians were all consulted. However, speed was the essence. The first ship loaded with troops, equipment, and stores sailed by 7 December. A total of 16 ships were chartered, some of which made more than one voyage. The overland route was ready by the end of December and the first troops left Saint John by sleigh on 1 January 1862.

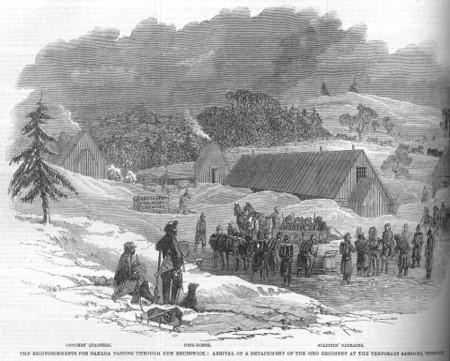

The route was divided into ten stages of about 30 miles each. Where suitable accommodations were not available, temporary camps were built such as the one at Petersville, New Brunswick. Detachments of the Military Train, Army Hospital Corps, and Commissariat Staff Corps were located at each of the staging stops. The movement of troops was regulated by telegraph.

Local contractors provided the open sleighs. The careful preplanning minimized the number of cold weather injuries. Desertion was a constant concern, and nine soldiers were lured away by American “crimps” as they travelled through New Brunswick. Fortunately, the diplomatic crisis had been resolved by late December and the Southern Commissioners had been released. This meant that the anticipated interference by American troops did not occur. This also resulted in the scaling back of the number of reinforcements.

British reinforcements arriving at Camp Petersville.

By 13 March 1862, six battalions of infantry, three field artillery and six garrison artillery batteries, two companies of engineers, two battalions of the Military Train, and detachments of the Army Hospital Corps and Commissariat Staff Corps had passed along the route.

This included the guns and equipment of the field batteries and a quantity of military stores.

The existing garrison in British North America had been reinforced by four battalions of infantry, two batteries of garrison artillery, and three field artillery batteries earlier in 1861.Four battalions of infantry, two batteries of field artillery and two of garrison artillery were added to Nova Scotia Command during the Trent Affair. This was a substantial reinforcement. Because of the relaxation in tensions, some of the troops began returning to England as soon as the summer of 1862. Those that remained, along with the militia they had trained, helped to defend British North American against the Fenian Raids four years later. The camp at Petersville is still in use.

Gary Campbell, PhD, is a retired Canadian Army Logistics officer. He has a special interest in logistics history, especially where it involves transportation. His articles on this subject have been published in several journals, both in Canada and abroad.