ROLL CALL, NEWSLETTER OF THE FRIENDS OF THE NEW BRUNSWICK MILITARY HISTORY MUSEUM/

AMIS/AMIES DE MUSEÉ D’HISTOIRE MILITAIRE DU NOUVEAU-BRUNSWICK

Volume 8, Issue 2 Summer 2022

Museum Prepares for Summer

by David C. Hughes

It has been a busy few months here at the NBMHM as we get ready for the summer season.

Since the last Friends of the NBMHM Newsletter we have been fortunate to have brought on board four soldiers from the Return to Duty program and from the Base Training List. Even though their time at the museum is limited their work here is very much appreciated. In addition, the NBMHM has been given funding to hire a summer student who will fill the role of Researcher and Guide for the month of July.

On 9 May I started in my new civilian role at the Museum as the Executive Director. I would like to extend my thanks to all the Friends who have given me advice, guidance, and support over the past year while I was serving as the Acting Director/Museum Officer. Getting the job as Executive Director of the NBMHM is truly a dream come true for me and I am excited about the immense potential of the museum and look forward to starting on new projects.

Part of preparing for the summer season is the plan to get our collection of tracked vehicles, wheeled vehicles, and field guns out of the parking lot where they are currently being stored, and back out around the museum grounds where they can be more properly displayed and more easily viewed by visitors to the museum.

They were taken off the grass due to an oil leak from one of the vehicles and the environmental concerns it posed. Before the vehicle collection can be put back in its proper place the vehicles will need to be drained of all POL (petroleum, oil, and lubricants) and then properly sealed to prevent future problems. Then, there is then the issue of creating a means of getting the vehicles onto rubber, crushed rock, or concrete pads around the museum to prevent them from sinking up to their axles in the mud. At the same time as we face those challenges most of the vehicles in the collection need a coat of paint and some TLC. This is a big project that will require the suppor tof many different units and entities on Base Gagetown, as well as the help of volunteers.

We have also started the process of bringing back the NBMHM gift shop. In partnership with the CANEX the gift shop will be up and running this summer. We’re planning to have books, model kits, replica badges, T-shirts, and other items, all with a New Brunswick military history flavour.

Now that the Executive Director of the NBMHM has been hired, job ads for the Curator and a Museum Assistant will be running soon. We are looking forward to expanding the team and bringing in people in these two new full-time positions. The extra “horsepower” is definitely needed as we have many challenges ahead to bring our wonderful NBMHM closer to its full potential. I hope to see you all this summer at the museum!

David C Hughes ,CD is Executive Director of the NBMHM.

(Harold Skaarup Photo)

Ferret Scout Car Mk 1, CFR 54-82608. NBMHM Vehicle Park. Ferret armoured Scout car was designed by the British for reconnaissance purpose and was produced between 1952 and 1971. It was built from an all-welded monocoque steel body, making the vehicle lower but also making the drive extremely noisy inside as all the running gear was within the enclosed body with the crew. Four-wheel drive was incorporated together with “Run flat” tires (which kept their shape even if punctured in battle thus enabling a vehicle to drive to safety). The Canadian Army had 124 in service from 1954 to 1981, serving with the 8th Canadian Hussars (Princess Louise’s), and C Squadron, The Royal Canadian Dragoons, Royal Canadian Armoured Corps and 5th Canadian Division Training Centre at CFB Gagetown until they were replaced by the Lynx tracked reconnaissance vehicles.

(Harold Skaarup Photo)

M548A1 Carrier, Cargo, Full Tracked with winch, CFR 35479, 49E. Museum Vehicle Park. The M548 is an un-armoured tracked cargo carrier equipped with a rear cargo bed based on the M113 APC chassis. They have been used at CFB Gagetown by the 2nd Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment, 4th Artillery Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, and the 5th Canadian Division Training Centre.

Farley Mowat and Canada’s War Trophy Collection

by Harold Skaarup

In 1973, I was an Officer Cadet serving in the Militia and was posted to CFB Shilo, Manitoba, to take part in Phase 1 of the Reserve Officer University Training Plan (ROUTP), graduating as a 2nd Lieutenant on completion of the program. I had the opportunity to explore and examine many of the artillery pieces then on display in the RCA Museum’s collection and photographed them for future reference. This is a story about one of the AFVs that was in the collection.

(Harold Skaarup Photo)

The museum had a 7.5-cm StuG 40 (L-43) Assault Gun mounted on a Mk. III tank chassis, which was on display at the RCA Museum at that time. According to documentation compiled May- October 1945 and filed by Captain Farley Mowat with the Historical Section in Ottawa, registered in the Archives 10 September 1946, this vehicle is identified as Item 4 on page 12. This “specimen had been assigned to the defence of Amsterdam but did not come into action there. It was recovered from the Germans after their surrender, by the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada.” This vehicle was in running order when it was shipped to Canada.

I spoke at length with Captain (Retired) Farley Mowat, the well-known Canadian author of many books, including And No Birds Sang and The Regiment, about the collection that had been assembled in 1945 by the 1st Canadian Army Collection Team, and, with the great assistance of the staff at the Canadian War Museum (CWM), they managed to track down his record compiled in 1946. I used it extensively in the compilation of my book, Canadian War Trophies, and managed to get a copy into Farley’s hands shortly before he passed away in 2014.

The story didn’t end there. This StuG III was one of three located at CFB Shilo through the 1970s. It was loaned to a museum in Calgary, but later sold to an American collector who restored it to running condition using an engine from a firetruck. It was later shipped to England. Late one night I received a phone call from David Ridd, who had a restoration team in the UK, asking if I could confirm this was the StuG III Captain Mowat had brought to Canada. They had stripped the AFV down and had the serial numbers of the gun and hull. I was able to match them with Farley’s record.

(David Ridd Photo)

The StuG III underwent a major overhaul and restoration in England by David’s team for a museum in Belgium.

(David Ridd Photo)

The restored StuG III in the UK has made an appearance in at least three different movies to date. A second German Sturmgeschütz 40 Ausf G Assault Gun had been out on the range and is now in the CWM. A third may have been used as a location marker on the range, identity unknown. It appears to have gone back to Germany in exchange for a German Jagdpanzer Kanone90-mm Tank Destroyer, now with the RCA Museum.

The 14th Field Ambulance

by Dr. Paul E. Belliveau

The 14th Field Ambulance has the distinction of being the first unit of the Canadian Army Medical Corps created in New Brunswick. It was authorized by General Order 11/06 as a militia unit on 26 January 1906, and was headquartered in Saint John, N.B. After mobilization for service in the Canadian Expeditionary Force in August 1914, it sailed from the port city for Camp Shorncliffe, England. There, it provided medical services to Canadian soldiers until February 1917, when it was re- organized for field duty under the command of Lieutenant- Colonel G. G. Corbet from Saint John. The unit was officially attached to the 15thInfantry Brigade, 5th Canadian Division. When the 5thDivision was broken up in the spring of 1918, the ambulance was held in reserve until required at the front. It was finally called up and arrived in France on 6 June 1918, where it provided medical services to Canadian troops until the end of the First World War. After the Armistice, the 14thField Ambulance was demobilized in Toronto on 15 June 1919.

Back in Saint John, Lt.-Col. Corbet lobbied to have the 14th Field Ambulance reactivated in his hometown as a Militia Medical Unit. On 1 April 1920, the proposal was approved, and he was appointed Officer Commanding. For the next two years, Corbet and a few other officers spent their time on administrative and recruitment duties. The ambulance did not actually begin unit training until 1923. Like all other militia units across the country between the two world wars, it was drastically under strength and training was very sporadic.

(New Brunswick Military History Museum Collection, Harold Skaarup Photos)

The badge of the RCAMC consists of the rod of Asclepius (a serpent entwined around a staff) surrounded by a wreath of maple leaves, surmounted by the Royal Crown, with the name “Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps” on a scroll below. There are two versions of RCAMC badges. The snake faces to the left for male staff (King’s crown), and to the right (Queen’s crown) for female staff.

On the declaration of the Second World War in September 1939, it was found that the 14th Field Ambulance could not be brought up to strength due to the lack of available medically trained individuals and competition with other Saint John units for non- medical personnel. Army Headquarters therefore decided to move the unit to Moncton where the recruiting base appeared more lucrative.

The 14th Field Ambulance was officially mobilized as an active military unit in July 1940 and Lt.-Col. George A. Lyons, MD, was appointed Commanding Officer. In November, it moved its headquarters from Moncton to Camp Sussex and initiated basic training with a full complement of250 all ranks. In addition to Dr. Lyons, the other original medical officers were Drs. Paul Melanson, R. B. Eaton, F. J. Desmond, H. M. MacLean, and J. Arthur Melanson, all from the Moncton area. They were soon joined by other local physicians, surgeons, and dentists, including Drs. E. S. Stiles, A. L. Richardson, L. C. Lindley, J. G. McCarroll, Kelly MacLean, Len H. Reid, and Raoul Landry.

The 14th Field Ambulance in England in 1943. Front row: Unidentified, Drs. K. MacLean, P. Melanson, L. Reid, and R. Landry. Back row: Drs. A. Melanson, F. Desmond, E. Stiles, A. Richardson, and R. Eaton.

One year after mobilization, on 31 July 1941, the 14thField Ambulance sailed for England and landed in Liverpool on 19 August. The unit soon settled in the Aldershot area for more advance and collective training. One section of the unit, however, was selected to provide medical support to Force III which raided Spitsbergen on 25 August 1941. Meanwhile, back in England, Dr. MacLean’s A Company took up quarters at the summer mansion of a wealthy English aristocrat while Dr. Lyons, headquarters, and Dr. Richardson’s B Company were billeted in more conventional quarters near West Grindstead.

Lieutenant-Colonel Dr. Joseph Tanzman, OBE, Canadian Army Medical Corps. Born in Warsaw, Poland, Dr. Tanzman studied medicine at McGill University in Montreal, graduating in 1927. By 1930, he was in medical practice in Saint John. During the Second World War, Dr. Tanzman served overseas as the Commanding Officer of the 14th Field Ambulance. He was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) for his war service. After the war Dr. Tanzman returned to Saint John and his medical practice. He died in 1981.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3397098)

Personnel of the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps (RCAMC) loading a casualty into a Willys MB ambulance jeep, and a Ram Kangaroo APC in the background, Sonsbeck, Germany, 6 March 1945.

From the time the 14th Field Ambulance landed in England until D-Day, the unit participated in numerous military exercises in various parts of Great Britain, including a full-scale amphibious invasion of the Isle of Man. On 6 June 1944, the 14th Field Ambulance, which was attached to the 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade, 3rdCanadian Division, landed on the beaches of Normandy and by 1100 hours, the unit had established a dressing station at Banville-sur-Mer. As the assault battalions continued to push inland, the 14th Field Ambulance followed, gathering the wounded, and evacuating them to their mobile dressing stations located close behind the advancing line. The unit continued providing medical services to the 3rdCanadian Division through Caen, Falaise, Calais, Reichwald Forest, and Nijmegen, and was ultimately stationed at Aurich in Germany at war’s end. Higher headquarters selected the 14thField Ambulance as the medical unit to accompany the “Berlin Brigade,” which was intended to march on to Berlin; however, this order was later cancelled.

Following the cessation of hostilities in 1945, many members of the14th Field Ambulance were immediately repatriated back to Canada, while others were only released gradually as they were still needed in the military hospitals of occupied Europe. The last commanding officer of the unit in Europe was Dr. Joseph Tanzman of Saint John. Once demobilized, the ambulance returned to Reserve Force status with headquarters at Moncton and under the command of Lt.-Col. H. P. Melanson. The unit was tasked to support the 14th Infantry Brigade of the 5th Division in the Maritimes. Although it survived the 1947 reserve force reduction, by 1948 the unit’s total strength had declined to four officers and no other ranks. Moreover, according to the unit’s annual historical report, there was no training conducted.

On 31 March 1949, Lt.-Col. Melanson retired and the following day another local doctor, Captain R. J. Brown, was given command of the unit. He immediately initiated a successful recruiting drive and implemented an ambitious training program. By 31 March1950, he had been promoted to the rank of major and the unit had increased in strength to six officers and 47 other ranks. Over the next three years the officer cadre expanded to nine while the other ranks strength remained in the vicinity of 50. In the fall of 1953, Major Brown was deservingly promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel.

In 1954, with the nation-wide change in the structure of the reserves, the unit was redesignated 3rd Medical Company. During that year the unit successfully recruited eight Nursing Sisters and participated in two summer camps. Over the next decade, 3 Med Coy underwent several “ups and downs” depending largely on the Moncton professional medical community’s interest in things military.

Nursing Sisters from 3rd Medical Company at Camp Gagetown in 1957 practicing artificial respiration. From left to right: Lieutenants Corrine Boulay, Kathleen MacRae, Dorothy Hickey, Eileen Larracey, Hubert Poirier, and Anne Marie LeBel.

By 1960, the unit was commanded by Major A. P. Murphy and was down to nine officers and 23 other ranks. Nevertheless, the unit continued conducting intensive garrison training and attended at least two camps each summer, providing medical services on various combined exercises, and participating in garrison and Remembrance Day parades. With the reorganization of the Canadian Forces in the sixties, in December 1964, the 3rd Medical Company was disbanded. Although dissolved as an independent unit, the company did manage to perpetuate its name by providing a small medical section to the newly created Moncton Service Battalion.

Paul E. Belliveau, BSc, MSc, PhD, CD was Atlantic Regional Manager of Laboratories for the Federal Department of Environment. He also served in the militia from 1960 to 1994 retiring with the rank of major as a Senior Staff Officer at the NB/PEI District Headquarters. Paul has authored a number of military history books, including (1) To Kill a Battalion (2) HMCS Coverdale: Riverview’s Forgotten Navy Base and (3) Percy Guthrie and the MacLean Kilties.

New Brunswickers and the American Civil War

by Troy Middleton

The American Civil War was a pivotal time in North American history. This war took place just prior to Confederation, and in part was the cause for British North American union. It was a violent and deadly time, and, although no one is now proud of it, our American neighbors still revere the men and women who took part and, in many cases, sacrificed everything for their cause. As Canadians, we also have the right to admire the men and women from here who participated in that terrible war. Through our research, Coy. I of the 20thMaine have identified over 4,000 Atlantic Canadians who served in the conflict with well over half coming from New Brunswick. Enlisting in the ranks of both armies most served the North, while some signed up to fight for the South. Many reasons can begiven for a “Canadian” to take up the fight. At that time, borders were mainly an idea, and many would have been working in the U.S. Others, working here on farms, or toiling in mills, warehouses, or docks looked at the war as a chance for adventure, or even money as bounties were paid to enlistees. Still others believed in the cause, no matter what they thought that cause was, and felt it their duty to help their neighbours.

U.S. Civil War re-enactors from Company I of the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment plan an event in Saint Andrews this weekend. From left are Lindsay Titus, Troy Middleton, Larry Burden, Janet Burden, Colin Moore, Steven Norman and Bruce Barber. (Photo courtesy of Larry Burden)

Between 33,000 and 55,000 men from British North America enlisted in the war, almost all of them fighting for Union forces.

Guy Landry, right, of Madawaska County took part in a re-enactment of the Battle of Gettysburg in 2018. (Photo courtesy of Larry Burden)

Sarah Emma Edmunds from Magaguadavic is the most famous New Brunswicker who took part in the war. Born in 1841 to a poor farmer in New Brunswick, she escaped an arranged marriage between her and one of her father’s creditors, “disguised herself to a man and emigrated to the United States”. She served in the Civil War as a soldier in Company F of the Second Michigan Volunteer Infantry Regiment, under the name of Franklin Thompson.

There are many other Canadians who served in the war, whose names have been lost to history. Below are just some of the New Brunswickers who enlisted.

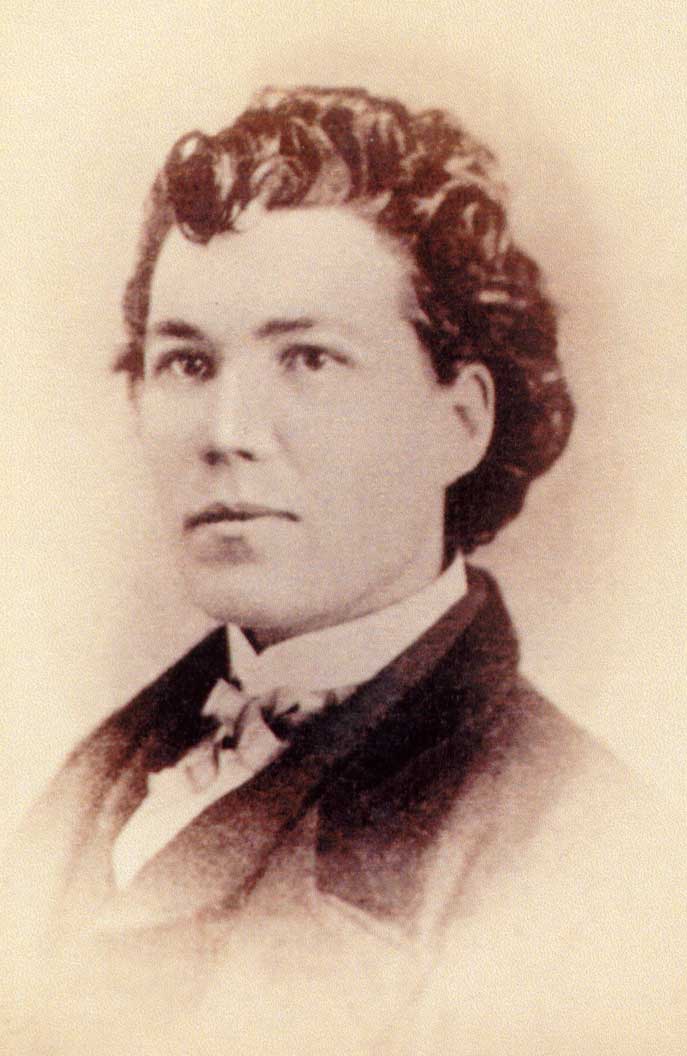

Cpl. Nathan J. Dunphy, 11th Maine Infantry, 1861. (Photo courtesy of the Maine State Archives Collection)

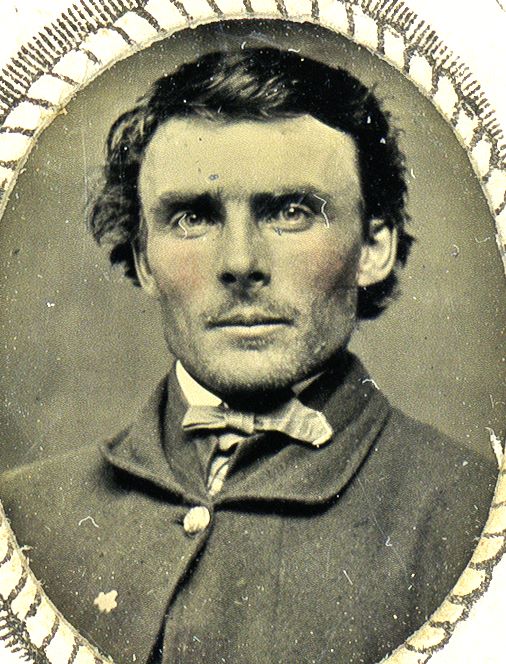

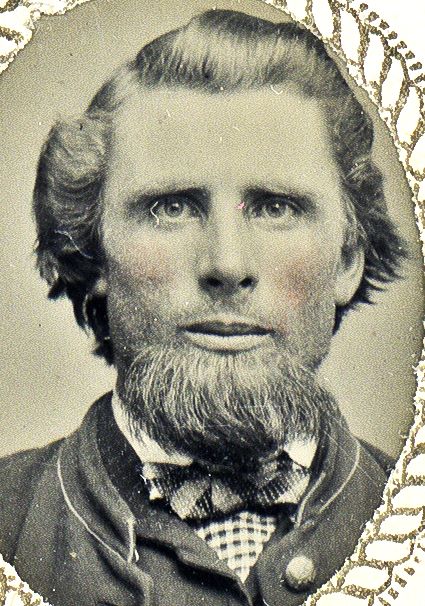

Cpl. Benjamin F. Dunphy, 11th Maine Infantry, 1861. (Photo courtesy of the Maine State Archives Collection)

Upon discharge Nathan and Benjamin re-enlisted with the Veteran Volunteers on 4 January 1864 and mustered out 2 February June 1865. He enlisted with the 6thBattery of the Maine Light Artillery on 6 February 1862. Capt. Edwin B. Dow commanded the battery.

Sgt. Nathan J. Dunphy (born 25 August 1839) served along with his brothers Pvt. James E. Dunphy (born 1843) and Cpl. Benjamin F. Dunphy (born 7 July 1839). Born in Blissfield, NB, Nathan enlisted in Co. H, 11th Maine Infantry on 4 November 1866. James was wounded during his service and took his discharge 18 November 1864. Nathan passed away on 7 May 1915 in Togus, Maine and was buried in Dover Cemetery. Benjamin died on 15 March 1917 in Sebec, Maine and was interred in Lee Cemetery.

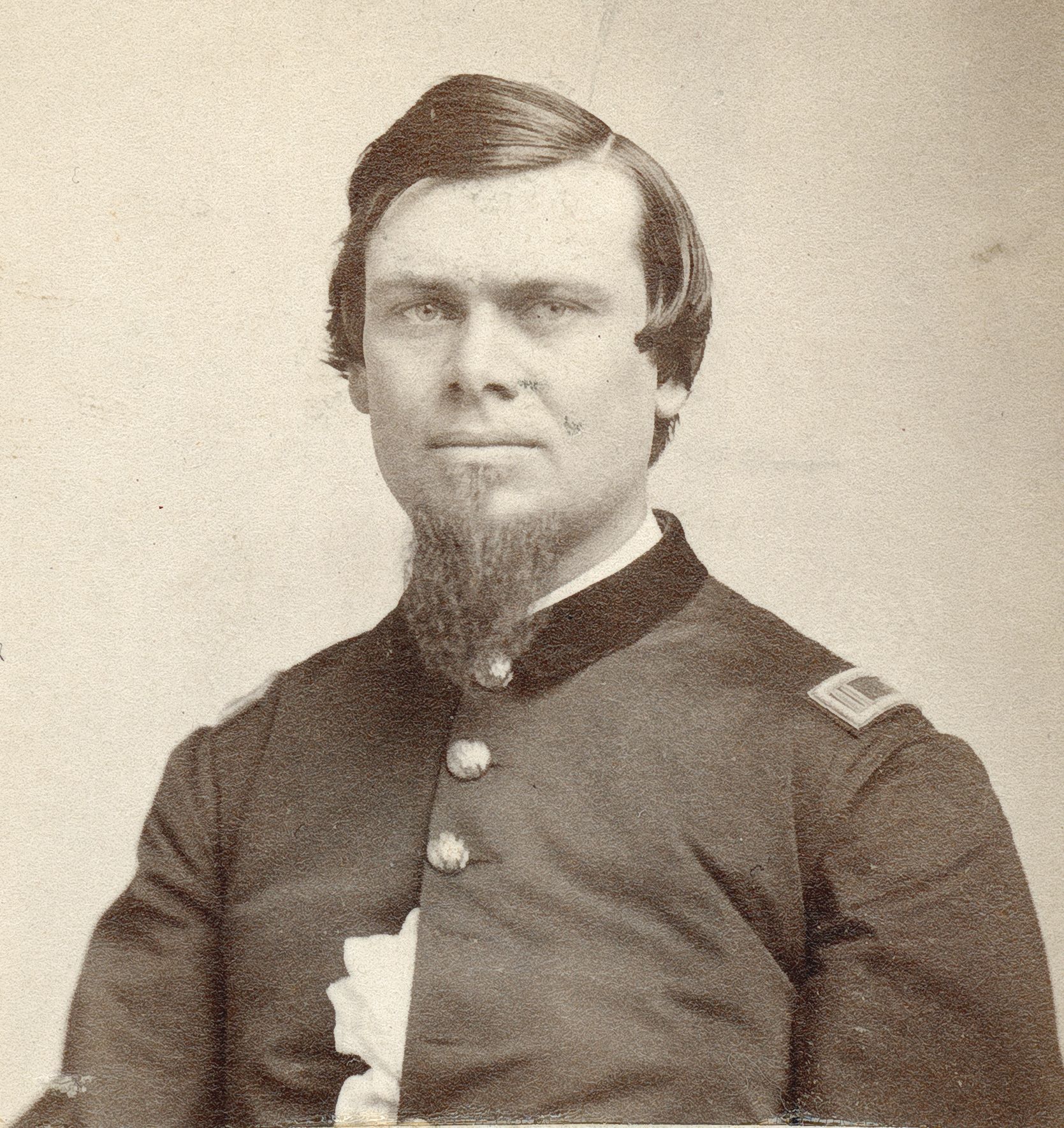

Carte de Visite of Captain Edwin B. Dow, 6th Battery, 1st Maine Mounted Light Artillery. (Photo courtesy of the Maine State Archives Collection)

Capt. Edwin B. Dow was born in Shefield, NB, on 20 June 1835. He enlisted with the 6thBattery of the Maine Light Artillery on 6 February 1862. Capt. Dow commanded the battery during the Battle of Gettysburg. He passed away in New York on 29 June 1917 and was interred in Arlington Cemetery.

2Lt. John E. Bailey, 7th Maine Infantry. (Photo courtesy of the Maine State Archives Collection)

2Lt. John E. Bailey was born in Fredericton, NB in 1840. He enlisted with Co. I, 7th Maine Infantry on 11 August 1861 and rose through the ranks, obtaining the rank of 2nd Lt. His right leg was amputated due to a severe wound he received on 12 July 1864 during the Battle of Fort Stevens. He succumbed to his wound and passed away on 30 July 1864 and was interred in Arlington Cemetery.

2nd Lt. Jacob E. Carvell was born 25 July 1834 in Newcastle, NB. He was living in Greenville, Mississippi when the war broke out he enlisted with the 22nd Mississippi Inf. After serving for a year he then enlisted with the 18th Virginia Cavalry and rose to the rank of 2nd Lt. by war’s end. In 1873, he joined the newly formed North West Mounted Police with the commission of Superintendent and took part in the historic march west. After three years of service with the NWMP he resigned and moved back to Virginia settling in Rileyville where he passed away in June 1902. Worthy to note, some of his descendants still reside in Rileyville on Carvell Lane.

Troy Middleton was born in New Brunswick and grew up in Maugerville. In June 2021, he released from the Canadian Forces and is presently enrolled at Athabasca University studying heritage resource management. He is a volunteer at the NBMHM and a member of the board for the New Brunswick Historical Society. He has been a member of Company I, 20th Maine re-enactment group since it formed in the early nineties and is currently its president.

**

My articles for Friends of the NBMHM Newsletters of the past:

Battle of Hong Kong, December 1941, Newsletter March 2015

The winter of December1941 was a hard one for Canada and its allies. The Japanese attack on the Hawaiian Island of Oahu on 7 Dec took most of the headlines, but Canadians were already involved in the Pacific theatre, having sent soldiers to Hong Kong just before the conflict began. Britain had first thought of Japan as a threat with the ending of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in the early 1920s, a threat which increased with the expansion of the Sino-Japanese War. On 21 October 1938 the Japanese occupied Canton (Guangzhou) and Hong Kong was effectively surrounded. Various British Defence studies had already concluded that Hong Kong would be extremely hard to defend in the event of a Japanese attack, but in the mid-1930s, work had begun on new defences. Although Winston Churchill and his army chiefs initially decided against sending more troops to the colony, they reversed their decision in September 1941 in the belief that additional reinforcements would provide a military deterrent against the Japanese.

In the fall of 1941, the British government accepted an offer by the Canadian Government to send two infantry battalions and a brigade headquarters (1,975personnel) to reinforce the Hong Kong garrison. The Canadian battalions were the Royal Rifles of Canada from Quebec and the Winnipeg Grenadiers from Manitoba.

The Royal Rifles were serving in New Brunswick where they recruited a large number of soldiers from across the province as well as from PEI and Nova Scotia. In the fall of 1941 these soldiers were deployed to Gander, Newfoundland, where they served on Coastal Defence duties. From there they redeployed to Valcartier where they were outfitted for tropical operations. They travelled by train to the port of Vancouver where they joined up with the Winnipeg Grenadiers. These two units were formed into a formation designated as “C Force” and on 27 October they embarked on board the troopship Awatea and the armed merchant cruiser Prince Robert. They arrived in Hong Kong on 16 November 1941, but without all of their equipment as a ship carrying their vehicles was diverted to Manila at the outbreak of war.

(IWM Photo, KF 189)

Canadian soldiers on exercise in the hills on Hong Kong Island before the Japanese invasion.

The Royal Rifles had served only in Newfoundland and New Brunswick prior to their duty in Hong Kong, and the Winnipeg Grenadiers had been serving in Jamaica. As a result, many of these Canadian soldiers did not have much field experience before arriving in Hong Kong. Unfortunately, these were the soldiers who found themselves engaged in the Battle of Hong Kong which began on 8 December 1941 and ended on 25 December 1941 with the surrender of the Crown colony to the Empire of Japan. More than 100 casualties suffered by the Royal Rifles during this battle were soldiers recruited from New Brunswick.

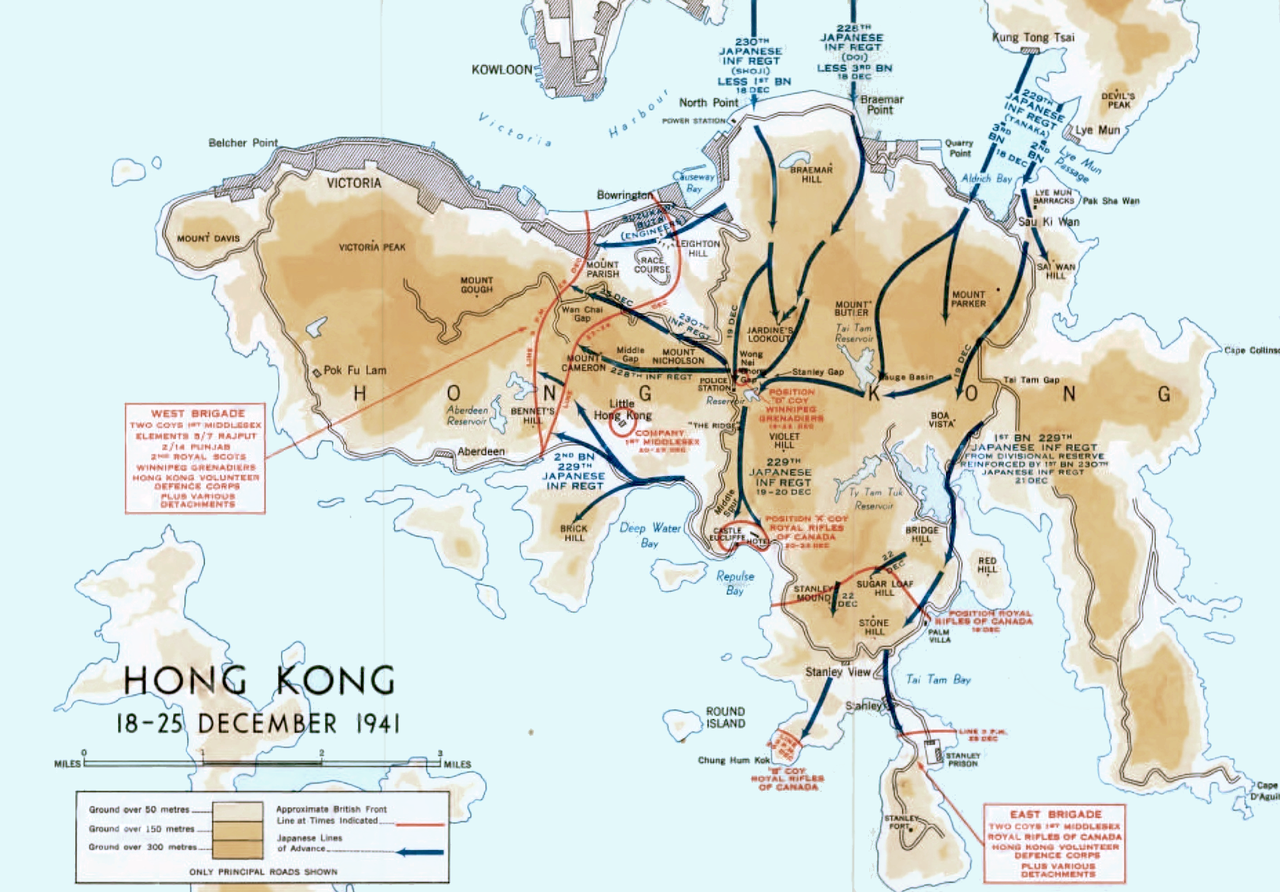

C. C. J. Bond / Historical Section, General Staff, Canadian Army – Stacey, C. P., maps drawn by C. C. J. Bond (1956) [1955]. Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War. Volume I: Six Year of War: The Army in Canada, Britain and the Pacific(PDF). (2nd rev. online ed.). Ottawa: By Authority of the Minister of National Defence. OCLC 917731527). Map compiled and drawn by Historical Section, General Staff, Canadian Army.

Map of the Battle of Hong Kong Island, 18-25 December 1941.

The Japanese attack began shortly after 08:00 on 8 December 1941 less than eight hours after the Attack on Pearl Harbor. British, Canadian and Indian forces, commanded by Major-General Christopher Maltby supported by the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps resisted the Japanese invasion by the Japanese 21st, 23rd and the38th Regiments, commanded by Lieutenant General Takashi Sakai. Some 52,000 Japanese assaulted the 14.000 Hong Kong defenders, most of whom lacked the recent combat experience of their opponents.

The colony had no significant air defence. The Commonwealth forces decided against holding the Sham Chun River which separated Hong Kong from the mainland and instead established three battalions in a defence position known as the Gin Drinkers’ Line across the hills. The Japanese 38th Infantry under the command of Major General Takaishi Sakai quickly forded the Sham Chun River by using temporary bridges. Early on 10 December1941 the 228th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel Teihichi, of the 38th Division attacked the Commonwealth defences at the Shing Mun Redoubt defended by the 2nd Battalion Royal Scots. The line was breached in five hours and later that day the Royal Scots also withdrew from Golden Hill. D company of the Royal Scots counter-attacked and captured Golden Hill. By 10:00am the hill was again taken by the Japanese. This made the situation on the New Territories and Kowloon untenable and the evacuation from them began on 11 December 1941 under aerial bombardment and artillery barrage. Where possible, military and harbour facilities were demolished before the withdrawal. By 13 December, the 5/7 Rajputs of the British Indian Army, the last Commonwealth troops on the mainland had retreated to Hong Kong Island.

MGen Maltby organised the defence of the island, splitting it between an East Brigade and a West Brigade. On 15 December, the Japanese began systematic bombardment of the island’s North Shore. Two demands for surrender were made on 13 December and 17 December. When these were rejected, Japanese forces crossed the harbour on the evening of 18 December and landed on the island’s North-East. That night, approximately 20gunners were massacred at the Sai Wan Battery after they had surrendered. There was a further massacre of prisoners, this time of medical staff, in the Salesian Mission on Chai Wan Road. In both cases, a few men survived to tell the story.

On the morning of 19 December fierce fighting continued on Hong Kong Island as the Japanese annihilated the headquarters of West Brigade. A British counter-attack could not force them from the Wong Nai Chung Gap that secured the passage between the north coast at Causeway Bay and the secluded southern parts of the island. From 20 December, the island became split in two with the British Commonwealth forces still holding out around the Stanley peninsula and in the West of the island. At the same time, water supplies started to run short as the Japanese captured the island’s reservoirs.

On the morning of 25 December, Japanese soldiers entered the British field hospital at St. Stephen’s College, and tortured and killed a large number of injured soldiers, along with the medical staff. By the afternoon of 25 December 1941, it was clear that further resistance would be futile and British colonial officials headed by the Governor of Hong Kong, Sir Mark Aitchison Young, surrendered. The garrison had held out for 17 days.

(Hong Kong Archives Photo)

228th Japanese Infantry Regiment enters Hong Kong, 8 December 1941.

The Allied dead from the campaign, including British, Canadian and Indian soldiers, were eventually interred at the Sai Wan Military Cemetery and Stanley Military Cemetery. A total of 1,528 soldiers, mainly Commonwealth, are buried there. At the end of February 1942, The Japanese government stated that numbers of prisoners of war in Hong Kong were: British 5,072, Canadian 1,689, Indian 3,829, others357, for a total of 10,947. Of the Canadians captured during the battle, 267 subsequently perished in Japanese prisoner of war camps.

Following the battle, John Robert Osborn was awarded the Victoria Cross. After seeing a Japanese grenade roll in through the doorway of the building Osborn and his fellow Canadian Winnipeg Grenadiers had been garrisoning, he took off his helmet and threw himself on the grenade, saving the lives of over 10 other Canadian soldiers.[1]

Canada responded to the outbreak of war with Japan by significantly strengthening its Pacific coastal defences, ultimately stationing more than 30,000 troops, 14 RCAF squadrons, and over 20 warships in British Columbia. Canadian forces also co-operated with the United States in clearing the Japanese from the Aleutian Islands off Alaska. Before Japan surrendered in August 1945, a Canadian cruiser, HMCS Uganda, participated in Pacific naval operations, two RCAF transport squadrons flew supplies in India and Burma, and communications specialists served in Australia.

[1] Internet:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Hong_Kong.

Battle of Hong Kong, New Brunswick Soldiers serving with the Royal Rifles of Canada

https://www.silverhawkauthor.com/post/second-world-war-battle-of-hong-kong-new-brunswick-soldiers-with-the-royal-rifles-of-canada-december-1941.