Estabrooks, Walter Ray, First World War Diary, Part 1 (Whiz Bangs and Woolly Bears)

Whiz Bangs & Woolly Bears, Walter Estabrooks First World War Diary, Part 1 of 4

This collection of stories from my grandfather, Walter Ray Estabrooks concerns his service overseas during the Great War.

(Estabrooks Family Photo)

Walter Ray Estabrooks, Royal Canadian Artillery ca. 1916.

Old Hands

“I have seen troops coming out of the line tired and dirty after a big push, make their first halt for a little rest. Sometimes a band would be waiting for them. Marching when not weary and with a good band will give some folks a tremendous thrill. But can you imagine a depleted unit coming out of the line from a hard position, tired, dirty, muddy and lousy, stumbling along just after dark, a few minutes halt just out of maximum gun range? “Fall in. Quick March.” Imagine that a band has been waiting for them and what it would feel like as it begins playing “The British Grenadiers.” The men would hunch their equipment up higher on their backs and their shoulders would straighten up. They would all have fallen in line four abreast without an order. No need for left-right. The muddy boots would seem to lighten up, and darned if the feet don’t seem to get the beat of the music. They are old hands, and would soon be disappearing into the night." Walter R. Estabrooks

Whiz Bangs

For the curious, a Whiz-Bang was an artillery shell fired by the Germans. It traveled with great speed, and was fired by a fast action gun. There was not much time to duck as one just heard Whiz. Bang! A Woolly Bear was another type of shell that was used for demolition, and when it burst on impact, it made a big hole and left a tremendous cloud of black smoke. They were slower than a Whiz-Bang and could be ducked by a man with a sixth sense.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3521831)

German Great War 7.7-cm Feldkanone 96 n.A., nick-named a "whiz-bang", captured by Canadians at Thelus, Vimy Ridge, April 1917.

Introduction to WRE and the Great War

Wars and battles are very strange things. Trying to understand how they start, who did what and how one suddenly finds young men and women from North America fighting and dying on the historic grounds of other nations, notably in Europe in the last century, is difficult indeed. Both of my grandfathers, Frederik Skaarup and Walter Estabrooks fought as artillery gunners on the Western front. When you try to unravel how the “Great War” started, it is somewhat of a mystery. On Sunday, 28 June 1914 in Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina, a teenage Serbian named Gavrilo Princip assassinated the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austrian throne. In 1996, while on duty with the NATO-led Peace Stabilization Force (SFOR), I was stationed in Sarajevo for six months and had the opportunity to stand in Princip’s footsteps. The entire city had suffered terrible destruction during the war that ran there from 1992-95.

What had changed from 1914? In the summer of that year, few Canadians would or could have been aware that the spark set off by Prinzip would be one of a series of events that would lead to massive losses of life over the next four years. It unfolded somewhat like this:

The European continent had basically divided itself into two armed camps with Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy on one side and France and Russia on the other. Both had concerns over power and control and intended to go to war if necessary, to keep as much of it in their hands as possible. Unfortunately for Canadians, who were essentially still a British Colony at the time, Britain was tied to some profoundly serious agreements with other nations, particularly France. Although “Britain had no formal alliance with either side, no one in Canada knew that she did have these informal military understandings with France, and they were to prove almost equally binding.”[1]

On 23 July 1914, “Austria, supported by Germany, served a harsh ultimatum on Serbia, and on the 28th declared war. Two days later, Russia, the self-proclaimed protector of the Slav nations, mobilized. On 1 August, Germany declared war on Russia and two days later on France. Italy, claiming that she was committed to support Germany and Austria only in a defensive war, remained neutral until May 1915, then entered the war on the Allied side.” [2] Basically, a couple of disparate groups began to play the very ancient and unfortunate game of “you fight me, you fight my gang.”

As Europe rushed to arms, Britain mobilized its fleet. Germany invaded Belgium, whose neutrality had been guaranteed by Britain as well as Germany, and on 4 August 1914, Britain declared war on Germany. In 1914, when Britain was at war, Canada was also at war; and there was no distinction, although Canadians believed at the time that Britain's cause (in defence of Belgium) was just. Most however, genuinely believed that the war would be over before they could take part in it.[3]

It never turns out that way. In Bosnia-Herzegovina, allied nations tried to force a group of people to give up their historical holy sites, by bombing them. The soldiers advising their coalition governments said don’t do that, we are on the ground there and it will be unbelievably bad business if you don’t talk through a solution. The politicians went ahead and ordered the allied air forces to bomb them anyway, telling everyone it would all be over in three days. After 79 days of bombing a nation about the size of New Brunswick, the most powerful allied forces in the world were only able to knock out 13 armoured vehicles out of a hidden target group of 3,500. We didn’t win, and not one of the one million refugees created during the event was helped until long after the damage had been done. No one “won”.

I have examined a number of records in Canadian historical archives, and found documents that stated, “in the First World War the Canadian Corps achieved a reputation unsurpassed in the allied armies. 619,636 men and women served in the Canadian Army in the First World War, and of these 59,544 gave their lives and another 172,950 were wounded.” [4]

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3395567)

Communications trench, September 1916.

My grandfather Walter Estabrooks had truly clear memories of his experiences in the trenches at Vimy Ridge (9-12 Apr 1917), Passchendaele (31 Jul-10 Nov 1917) and Hill 70 (15-25 Aug 1917), during the First World War. He also spoke about a few the more interesting events that he took part in overseas. I wrote him several letters and have written his experiences down as he related them to me. I attempted to weave his recollections into the events recorded in his diary. I provided a brief view on the wider course of the war by including extracts from the official war records. The data that I gleaned from my grandfather has been collectively placed as a story within a story, which I call “Whiz Bangs and Woolly Bears.”

As a boy I used to listen to his stories while we worked around his two large Belgian workhorses, Smoky and Trigger, on his farm in Carleton County, New Brunswick. The horses generated a lot of “pitchfork and shovel work” for a young fellow visiting the farm, but I learned to like working with the team. We used them to haul the old steel and wood mowing machine to cut hay, then to go around again with a long tined rake to gather it up into neat rows, and a third time to pull a big hay loader to get the hay onto a wagon. A long black fork with opposable tines hung down from the barn roof, and the team driver had to back the horses up to lower the rope and drop the fork into the mound of hay on the wagon. Once the hooks were snapped in place, Gramp would show me how to guide the team to haul the fork full of hay up into the hayloft without tearing it out of the roof.

In between these chores, or while we were splitting wood in the woodshed, my grandfather would tell me about his experiences during the Great War. Gramp never talked much about the bitter side of that war, although what was left unsaid about the other things that happened at that time led me to ask him more questions. He would often give an interesting answer, based on experiences that had happened to him over 50 years ago, and yet which seemed clearer to him than other events much closer to the present. He could talk about those experiences at great length, although he would sum up the events in his life since that time in only a few sentences. Many years later I joined the army, and began to have some interesting experiences myself, and it was then that I began to realize what it was that made my grandfather’s stories so interesting. It was the telling of the story with a clear and often humorous memory of people he worked with, trained with, and grew to know in a way that only people who have undergone stressful circumstances together can know each other, that made the stories interesting. It was important to my grandfather to remember the names and their stories of the soldiers he served with, and so it became important to me as well.

As I grew older, I began to read more about the “Great War” and to develop a tremendous interest in history. I visited European battlefields during Army Staff College training, and while there, I tried to get a feel for what had happened to my two grandfathers and the me they served with. I also read a copy of his war diary that had been typed up by one of his six children, my Aunt Wilhelmine.[5]

I was away at school at the age of 18 when I began to write to my grandfather to ask him for more details about the war and the things that he wrote about in his diary. Although I am older now, and he is long gone, the stories are still interesting. If you have the interest, I have attached a web page I put together where you can read more of the story free.

My grandfather, Walter Ray Estabrooks survived and got back to Halifax in 1919 on 24 May 1919, at the age of 28 years. Incredibly, he lived to be 94 years old and still had a clear and vivid memory of the events of the Great War that he had personally experienced. The indelible impression that the left on him was passed on to me while we were working with his farm horses called Smoky and Trigger. I have not forgotten. I hope my children and grandchildren will read them as you may, and stop to think about the incredible times their great grandfathers experienced, and more importantly, to pass the stories on without having to experience the hardships they endured first hand.

As one of Walter’s grandsons, and a retired Major having served in the Canadian Forces, I can only reinforce the importance of learning all that you can from your grandparents while they are alive. Write their stories down and pass them on to your family along with your own stories. Share them, it is how we learn and grow.

[1]LCol D.J. Goodspeed, The Armed Forces of Canada 1867-1967, Directorate of History, Canadian Forces Headquarters, Ottawa, 1967, p. 29.

[2]LCol D.J. Goodspeed, The Armed Forces of Canada 1867-1967, p. 29.

[3] Ibid, p. 29.

[4] Ibid, p. 67.

[5] The Diary of Walter R. Estabrooks, 1916-1919. Personal Notes and Papers.

Walter Ray Estabrooks

Walter was a son of Joseph Leonard Estabrooks and Catherine Mildred Peed (Kate, first generation Irish). He was born 13 November 1890 in Upper Waterville, New Brunswick. His ancestors were Anglo-Dutch Flemings, some of whom had originally immigrated to Boston from Enfield, England in 1660, settling nearby in Boxford, Massachusetts. One of Walter's ancestors was Elijah Estabrooks, who was also one of the first settlers to come to the Saint John River (then in Nova Scotia, now in New Brunswick, Canada) in 1763. (Elijah is buried at Jemseg, New Brunswick).

Walter had joined the Royal Canadian Artillery in Woodstock, New Brunswick, and served with the 10th Battery, 4th Brigade in 1912 and 1913 during exercises in Petawawa. (The 10th Battery was formed in 1892 and given its number in 1895). He went overseas and served with the 32nd Field Battery, 8th Army Brigade (HQ in Ottawa), Canadian Field Artillery, on 24 December 1916.

When I wrote to him about his life before the war, he told me the following:

“When I was a teenager I went to the Upper Waterville School. We did a lot of swimming in the creek. Trout fishing was good then in the brook, and eels were plentiful in the creek. I played baseball quite a lot. We used to play against the Wilmot school and about always got licked. I got to be a good swimmer and skater on ice and rollers. I could strike a ball into the next county but was no good as a catcher. We always played barehanded. Our post office was at Waterville, with mail three days a week. Father always had a spare horse or colt that I could ride three days a week to Waterville and back, a little over four miles after school. I don't think I was ever in a saddle until after I was 15 and went to drill at Sussex with the old 10th Battery 12-pounder muzzle loaders.” (I am not sure if he meant the Ordnance 12-pounder Breach Loading Gun or the Ordnance 9-pounder Rifled Muzzle Loading Gun, both types shown below)

(Author Photo)

Rifled Breech Loading 12-pounder Gun, Royal Artillery Park, Halifax, Nova Scotia.

(Author Photo)

Rifled Muzzle Loading 9-pounder Gun, Royal Artillery Park, Halifax, Nova Scotia.

(Estabrooks Family Photo)

Artillery summer camp, Sussex, New Brunswick, about 1912. Walter is mounted on the horse with a dot marked under it. The guns appear to be Ordnance QF 18-pounders with limbers.

.avif)

(Author Photo)

Ordnance QF 18-pounder Gun, Royal Artillery Park, Halifax.

When I was discussing the kind of military training we undergo in the Canadian Forces today, I asked Gramp about the military training they had undergone in Petawawa during his pre-war training. He described it this way.

“The training you are going through I would have got a great kick out of 60 years ago. We had our morning run before breakfast. Section gun drill. Riding school. A lot of the farm boys had never been in a saddle, and had to learn to keep their toes turned in and not let the stirrup slide back to the instep straight line from the shoulders, middle thigh and ankles etc. The 18-pounder had to be kept clean and oiled and checked ready for action. Occasional route march and usual fatigues, not too strenuous a life compared to what you are going through. Most of our officer's were as green as we were. I had from two to three weeks a year in the militia from 1906 until the First War.”

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4474053)

18-pounder Field Gun, 15 Apr 1915, CFA.

“I joined the artillery because I had trained in the militia. I trained or drilled as we called it, in the 10th Field Battery, (4th Brigade) from 1906-1914. At Sussex one year, Watson Field, Woodstock, one year at Petawawa in 1912.”

Colonel G.W.L. Nicholson wrote, "The year 1912 saw the fullest use being made of Petawawa since the camp's inauguration...In addition to the resumption of a partial programme of combined training for the Permanent Force, there was the greatest assembly of artillery units of the Active Militia in the camp's history. For the first time the three field brigades from the Maritime Provinces (The 3rd Brigade C.F.A. (17th Sydney, 18th Antigonish, 37th Charlottetown Batteries); the 4th Brigade C.F.A. (10th Woodstock, NB, 12th Newcastle, NB, 19th Moncton Batteries); and the 11th Brigade C.F.A. (27th Digby, 28th Pictou, 29th Yarmouth Batteries)) came to Petawawa for their full sixteen days of training and practice firing...in addition...the 3rd New Brunswick and 4th Prince Edward Island heavy Brigades send detachments to do practice firing." A total of 5,176 officers and men of the Militia Artillery and 2,609 horses trained at the big central camp that summer. Col G.W.L. Nicholson CD, The Gunners of Canada, The History of the Royal Regiment of Canadian Artillery, Volume I 1534-1919, (McClelland and Stewart Limited, Toronto, 1967), p. 173.

Training in the summer in Petawawa “was like a try out for a long distance moving of men, horses, guns and equipment. The country we maneuvered in had been burned over the year before. The dust from the ashes on that sandy soil enveloped us to the extent that our horses sickened. I had my own horse Gillie. He was one of the few that completed the last ride for points that last day.”

He also told me about how his artillery battery transferred from New Brunswick to Ontario by the train.

(Artillery Postcard)

Ordnance QF 18-pounder with gun crew, possibly Petawawa, ca 1908-1912.

“The battery loaded up on flat and box cars, flats for the guns and box cars horses, six horses in a car. We worked all day in Woodstock loading. Money was scarce. George DeLong and I bought a pound of cheese and 25 cents worth of sweet biscuits and the rest for supper. Left Woodstock about 8 PM on the CPR via McAdam, St John to Sussex, getting there 2 PM the following day. I got train sick, as I had never been on a train before. I threw up cheese and biscuits all the way from McAdam to Sussex. Old Dan Gallagher the cook had brought half a barrel of baked beans from Merburg to Woodstock and on to Sussex. Hot weather the last of June and they were so sour that everyone was (sick).”

.avif)

(Estabrooks Family Photo)

Artillery personnel, Woodstock, New Brunswick about 1916. (Walter is marked with a penciled in x at the upper right).

Gramp told me that “that was the only time I was ever really homesick in my life. I got 9th grade with Allan Barter at the home school. That fall I did the chores and ploughed 40 acres with the horses we called Maud and Jess. Went the spring term to Jacksontown for 10th grade. Father moved buildings while I was ploughing to get money enough to pay our board. There were several wonderful girls in the grade. I think it was the best year of my teen-age life. I learned to dance the waltz. There are very few of that class living now.”

“I saw my first automobile about 1914. I remember when Queen Victoria died, I think in 1901. The news did not get around to the Atlantic until the next day. I finished 11th grade, which was the end of high school at that time, in June 1908. In the meantime, father had sold our old home and moved here in April 1908, and this has been the only home I have known ever since. I liked it up here, but it seemed a lot longer to walk home from Woodstock Friday nights.”

“There were no cars to hitch-hike and I could out walk or run a double tram. 16 miles, 4 hours. Father always gave me a lift back Sunday night. Father always kept workhorses that were good roaders. Winter, to get in Monday morning had to feed horses at four AM, to make it in by seven. I never had over 50 cents a week allowance. I saved up enough to take Jessie Young to the opening of the new Hayden and Glen Theatre. I could only get about the fourth row, the best in the Theatre. Most of the young people had cheaper seats in the balcony. She had an idea the balcony seats were higher, and peeved and peeved about it. I hadn't money enough left to buy treat, so walked her home. That ended that heartfelt romance.”

“I don't know how I ever made any impression on the girls. (It helped) if a boy had a decent horse and buggy. I had the best Dad in the world about that. I always found it best not to show off. Be a good skater and dancer, and pretty well keep one’s mouth shut made more (of an) impression on the girl that really counted.”

Walter kept a diary as a record of his experiences in the Canadian Army during the First World War, which came to be known as “The Great War” of 1914-1918.

The opening entry in his diary reads as follows:

Diary of Walter Ray Estabrooks, 1916 - 1919

“I, Walter R. Estabrooks, enlisted in the spring of 1916 with the 65th Depot Battery at Woodstock, New Brunswick. Stayed home until barracks (in what is now United Farmers' Store) were completed. Was issued uniform and number 335805, April 9th. Chris Armstrong, Miles Gibson, Dalton Rideout and I were made Sergeants of A, B, C and D Subs. We trained on Island Park until several horses and two guns arrived. Then went under canvas at Carvel's Flat (with) Major Price, Captain Berry, Lieutenants Armstrong, White and Winslow.”

Diary Notes and the Official Canadian History of the Great War

To place the events of Walter’s diary in context, short summaries of the events that took place at the time are extracted from the official war records and included for general reference. As related in the introduction, in 1914, when Britain was at war, Canada was also at war; there was no distinction, although Canadians believed at the time that Britain's cause (in defence of Belgium) was just. Most however, genuinely believed that the war would be over before they could take part in it.[5]

Canada's militia, of which Walter had been a part, was mobilized through the energy of Colonel Sam Hughes, (mentioned in the diary). Walter had to wait for the medical officer to authorize his release for overseas duty, and so he fortunately missed the initial slaughters of Allied forces and arrived in France when trench warfare had already settled in.

He was 15 when he first went to drill at Camp Sussex, New Brunswick, with the 10th Battery. In his own words,

“I drew my first uniform in June 1906, a week before going to camp. Dressed up in it as soon as I got home and had supper. Felt pretty big. Harnessed old Maud the bay mare in the single wagon and drove up the road to show off. Met Edna Rockwell at the Primitive Baptist Church. The uniform kind of bolstered my courage, and I asked her to have a drive with me. I could not think of anything to say, so asked her to sing. She sang several old songs. She couldn't think of anything to say either”.

Between 1906 and 1914 he trained for two weeks each year at Camp Sussex, New Brunswick, and then went via train to competition shoots at Petawawa, Ontario. While working on the B & A railroad in the spring of 1914 however, he came down with typhoid. Although he was able to go to camp 25 June to July 6th, he could not get by the medical officer until the spring of 1916. He trained in Woodstock, NB (along with six horses and one gun), where he had been a Sergeant in the militia and was an Acting Gunnery Staff Sergeant until he landed in England.

Walter’s diary records his experiences from basic training through to the battlefields of France. His early diary entries read as follows.

October 3rd, 1916

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3338281)

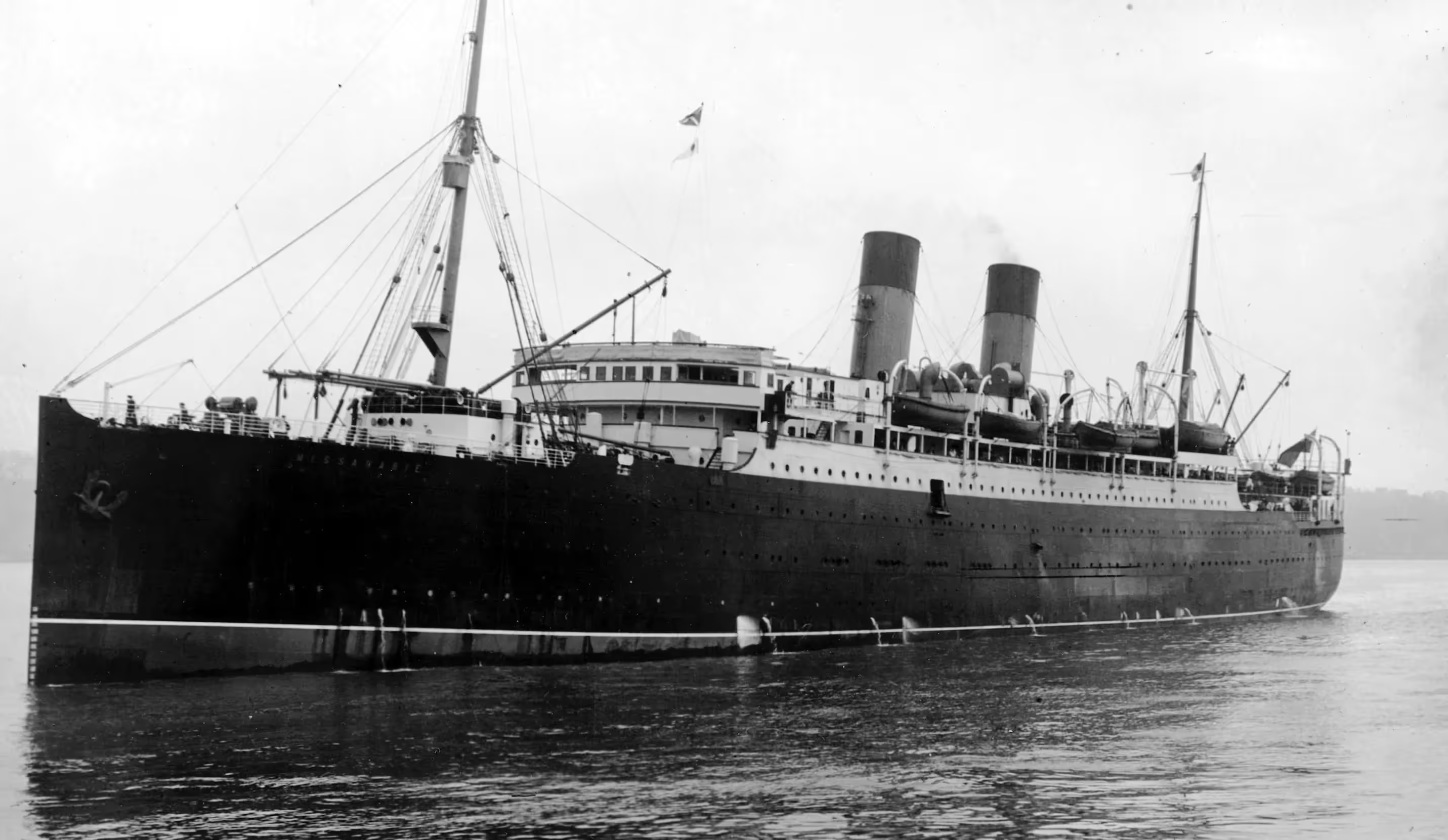

Embarked at Halifax on the Missanabi, and with two other troop ships and a destroyer docked at Liverpool.

As I went through the diary entries, I asked a number of questions. Here for example, he explained to me that he had embarked at Halifax on the 3rd of October and crossed to Liverpool on the CPR liner Missanabi in convoy with two other troop ships and a destroyer. They went the Northern route near Ireland, and down the Irish Sea to Liverpool. From there they were taken to Shorncliffe camp near Folkestone, where they were billeted in tents. There, on the strait of Dover on clear days they could see across to France.

October 13th

Entrained to Shornecliffe. Billeted in tents. Roll Call in the cobble stone paved barracks' square. Foggy wind blowing in off the North Sea. Stand at attention...answer your names...quick, mark time...stand at ease, etc. until 13th. Shot over miniature rifle range.

While at Shornecliffe, Walter was picked for training on the 4.5” Howitzer. He described these pieces of heavy artillery as, “A high angle of fire gun with unfixed ammunition. They used one charge for dropping a shell over a nearby hill, two charges for a hill farther away, and three charges for longer ranges, in a flat trajectory. Compared with the eighteen pound shell, the 4.5 weighed about 24 pounds. The eighteen pound shells were fixed ammunition, as they were in a cartridge case about 20” long and propelled by cordite. The three charges that propelled a 4.5 were filled with cordite, Nitro-Cellu Tuluene (NCT) and Tri Nitro Tuluene (TNT).

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3522268)

Canadian Corps Heavy Artillery in action during the advance on Arras, France, Sep 1918.

(Clive Prothero-Brooks Photo)

Ordnance QF 4.5-inch Howitzer, RCA Museum, CFB Shilo, Manitoba.

October 20th

On musketry. With tent crew on Folkestone piquet for having an untidy tent. Classes - Gunnery instruction on 4.5 howitzers. From 6:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m., visited Caesar's camp, Cheriton.

November 1st

Moved into married quarters - Risboro Barracks.

My grandfather told me that while he had trained in England in October and November, it had rained every night. Sir Sam Hughes had his outfit in tents on Caesar's Plains. He tried to get his men placed in barracks, and had some big brass down to review his outfit. They hovered over his men and congratulated him on having such a robust Canadian regiment that could stand it to be in tents. They could not however, get barracks for them. The men had been standing at attention in front of the individual tents. The big brass ordered stand at ease. Sam called them to attention again. He roared out “From now on, only two parades, church parade and pay parade”. He turned quickly and fell on his ass in the mud. In any event, from then on there was only one parade, pay parade.

November 9th

Social evening at Wesleyan Church, Sandgate. Met the singer, Miss Ludlow.

November 13th

Birthday. Parade to dentist. On piquet in the evening...chasing soldiers and girls up from Lower Lees, Folkestone.

November 17th, 1916

Received first letter from Canada.

November 20th

On 24 hour duty guarding one shell-shocked man at Moore barracks hospital. Played checkers with him during the day. Sat with him at meals in a long mess hall. At supper, ate my first rabbit stew. He made up his own cot, found a couple of blankets for me; said he never wakened until morning. I lay down and promptly went to sleep. Waking later...not opening my eyes, I could hear breathing above me. I opened my eyes and grabbed for ankles. Before I had a good grip he sprang clear, and back in bed, dropping my bandoleer he was holding over his head. Needless to say, it spoiled my nap.

November 25th

Marched to Hythe ranges, carrying Lee Enfield rifles and noon rations. Made my best marks on the 600-yard range.

November 25th

Weekend in London. Westminster Abbey. Houses of Parliament, Buckingham Palace. Cleopatra's Needle. Whitehall. Horse Guards. Bank of England Tower of London. London Bridge. Tower Bridge.

November 27th, 1916

Started Howitzer course.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3395353)

BL 6-inch 26 cwt Heavy Howitzer, Canadian Front, Feb 1918.

December 8th

Went on leave with Ed Duffy and Lee Bell. Went to London, went to a show. Took late train to Edinburgh. Got rooms at King George and Queen Mary Club. Saw old Scotch Parliament, Statue of Charles First, Tomb of Paul Knox, Edinborough University, National Scottish Museum, Edinborough Castle, and King’s Theatre in evening, Art Gallery. Went on bus to fourth bridge. Passed little bridge where Mary, Queen of Scotland met Rizzo and eloped.

(Bell Family Photo)

Private Lee Bell.

December 12th

Came back to London. Visited Royal British Museum, Banquet Hall of Charles 1st. Through Westminster Abby.

December 13th

Went through Tower of London, Regents Park, and Zoological Gardens.

December 17th

Entrained for Southampton. Boarded transport and landed at LeHarve, (France), the morning of December l9th. He told me about the move as they left Southampton and crossed to LeHarve, France, and went up through Rouen to the front line at Haut-Avesnes. The Canadians had just come off the battles of the Somme, and as the 18-pounders needed men, he and his friends Lee Bell and Ed Duffy were attached to the Division headquarters and eventually the 32nd Battery. There they took part in holding the line on the Arras and Vimy front during the winter of 1916-1917. They gave covering fire for infantry raids involving the Canadian Mounted Rifles (CMR), Royal Canadian Regiment (RCR), and Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI).

(The Canadian Army Order of Battle, 11 November 1918 lists the War Establishment of the 8th Army Brigade Canadian Field Artillery, 32nd Battery C.F.A. as having 5 Officers, 189 Other ranks, 165 horses and six 18-pounder guns. The Brigade also included an HQ, as well as the 24th Battery and 30th Battery, each with six 18-pounders, the 43rd (Howitzer) Battery with six 4.5-inch Howitzers, and the 8th Army Brigade Ammunition Column).

(Library & Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3405482)

Ordnance QF 18-pounder, RCA, ca. 1918.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3522764)

Canadian 2-inch medium trench mortar battery with 2-inch "Toffee Apple" style mortars and bombs, 31 July 1917.

Walter told me that a typical unlucky night would involve being on a work party to dig temporary emplacements for the trench mortar operating in no man's land, with nothing for protection but a shovel, and nothing to eat from six at night until seven in the morning. In his words, the “mud in the trenches was waist deep, and we spent most of the time dodging Whiz Bangs”. I asked him what a Whiz-Bang was, and drew this response:

“The Whiz-Bang was a field gun used by the Germans in the forward area as opposed to our 18-pounder. The shells were slightly under 3 feet and longer than ours. They traveled with great speed, and were fired by fast action guns, but did not have the strafing power of our 18's. Not much time to duck as one just heard Whiz. Bang! Our 18-pound shells were filled with bursting charges regulated by time fuse up to 21 seconds, and filled with about 100 steel bound bullets. The Whiz-Bangs were similar except the bullets were lead shrapnel. Our High Explosive (HE) shells burst on contact, and were filled with NCT. Woolly Bears were another problem for us”.

German Field Artillery Regiment crew and their 7.7-cm Feldkanone 96 n.A. probably in front of barracks building during training. 1914 Postcard. (Wikipedia)

%252C%2520(Serial%2520Nr.%25202398)%252C%2520Woodstock%252C%252011%2520Nov%25202017%2520(2).avif)

(Author Photo)

German Great War 7.7-cm Feldkanone 96 n.A., (Serial Nr. 2398), recently restored and mounted in front of the Woodstock Courthouse, New Brunswick. This is the type of gun that fired the Whiz Bang. Grandfather Frederick Skaarup fired these guns in action on the Western Front.

Needless to say, the use of military abbreviations is not something new, and of course on reading these terms I had to draft another letter, this time to ask about Woolly Bears. He replied,“A Woolly Bear was used for demolition, and could be compared with our 5.9's. It burst on impact, made a big hole and left a tremendous cloud of black smoke. They were slower than a Whiz-Bang and could be ducked by a man with a sixth sense”.

(Author Photo)

Ordnance BL 6-inch 26-cwt Howitzer, Saint John, New Brunswick (also referred to as the 5.9).

(Author Photo)

German Great War 15-cm Schwere Feldhaubitze 13 Howitzer, Kensington, Prince Edward Island. This is the type of gun that fired a Woolly Bear.

December l9th

Marched through Haffleur to Canadian Base.

December 20th

Marched down the long steps to rail yards in evening. Entrained, got a little sleep under seat. Arrived Rouen December 21st.

December 21st

Had a good feed at rest camp.

December 22nd

Up the lines. Thirty in a tiny boxcar. Unloaded. Packed. Several kilometres in pouring rain [near Haute-Avesnes].

December 23rd

Marched six kilometres (West) to Hermaville in pouring rain. Had to wring out our socks at third DAC (Northwest at) Frévin Capelle. Truck carrying our blankets and kit bags ran over embankment and crashed. Marched to LaHarrset 9th Brigade rear. Cold and wet. Slept on soft side of a brick floor in old sugar refinery.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 35222989)

Supply truck support Canadian heavy artillery in action during the advance East of Arras, France, Sep 1918.

December 24th

First day with 32nd Battery. Went on guard 6:00 p.m. with Corporal Creighton, Ed Duffy and Lee Bell. A group around singing carols. Some just singing. Machine gun fire up the line. Occasional gun flashes and flares lighting the sky.

December 25th, 1916

On guard. Bread, jam, cold beef, mustard pickles, tea for dinner. Supper - roast beef, mashed potatoes, cake, plum pudding, orange and coffee, (beer if you wanted it).

December 26th

First time on horseback since leaving Canada. Painted wagons with Wheelwright Cook. To dentist and gas school, afternoon.

January 4th, 1917

Lee Bell and I sent to guns with Bdr. Dobson. Joined B-sub. Guns, chalkpits at left of Sainte-Catharines. First night in a dugout. Boys had French bread and Oxo for lunch. Sgt. Cornelia O'Neil, Earnie Bennett, Evan Fitzpatrick, Jimmie Morrison, George Haddock, Dick Wickens, George Evans.

January 9th

Sent in front line with Bdr. Heney and Signaler Whitehouse. Front line full of mud. Got lost but eventually reached telephone station in an old mine shaft infested with rats and lice.

Walter told me that while they were on duty in the dugouts they took turns on watch, two hours on and two off for 48 hours. The dugouts had been an old chalk quarry mine, and were infested with big gray rats. “You had to cover your face when trying to sleep,” he said.

January 11th, 1917

On telephone from midnight 'til morning. We were relieved by Corporal Webb and Signaler Boyer.

January 12th

George Smith joined the battery.

(Imperial War Museum Photo, Q6420)

A flare going up exposing a fatigue party carrying duckboards over a support line trench at night, Cambrai, 12 Jan 1917.

January 13th

On carrying party to an Observeration Post (OP) in evening with experienced men. Guide says, “It's dark, be careful. We will go overland from second.” We were plodding along in single file... a loud pop up front. Everybody stopped but Estabrooks. He bumped into man leading...each with several sheets of corrugated on their backs. Crash...bang. Everybody flopped as a flare lit the sky. What fool! Did not know enough to stop when he heard a flare pistol. A machine gun sprayed us about a minute. Nobody answered - but I learned my first lesson.

January 15th

Carrying party to OP in the evening. Bosche took a crack at us with machine gun.

(German Army Photo, Bundesarchiv Bild 102-08071)

German First World War three-man Machine Gun crew manning a 7.62-mm MG08 mounted on a stand. One is the gunner, the second is the loader, the third is the spotter.

January 17th

Quiet day.

January 18th, 1917

Battery runner.

When I asked my grandfather about runners and dispatch riders, he said, “Each of the three battalions that formed the brigade had to supply a man to be attached to Brigade HQ, to be a runner, dispatch rider, go-fetcher. HQ was usually situated out of the line of observation from the front line. We carried orders to Battery Ammunition columns, and met motor cycle dispatch riders at the nearest place they could come. The motor cyclist HQ had three heavy cog drive cycles to be used when necessary. If the trip was not over a couple of miles, I would rather walk than drag a bicycle over rough country to reach a road going the way you needed to go. I could read maps and get to places, so I was unlucky enough to get several of the long distance trips”.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3194763)

Pack horses transporting ammunition to the 20th Battery, Royal Canadian Artillery. April 1917.

About officers, he commented on one particular incident: “I was accompanying a new officer that I had met in England from the gun position to OP. One of those long-range shells passed over us about a mile in the air. I paid no attention, but he dove for the ditch. By the time the sound got to us it was bursting near our ammo dump about four miles in the rear. He looked funny as he got up from the ditch, but that's when I realized that officers had to grow up the same as men in the ranks”.

January l9th

Fired 18 rounds. Went on guard.

January 20th

Gun laying practice.

January 21st

On party digging trench mortar emplacements. Mail in. Received box from home.

January 22nd

Short strafe. On working party until midnight. Sergeant Davies, Labey, Bert Bryan and two men from left section. When Bert's shovel got heavy he told stories. He was good.

There were lots of storytellers in the lines, and his friend Bert Bryan's stories were some of the best, depending on who the tale was about. This brought us around to stories about Passchendaele, which he described as:

“Passchendaele was just one glorious mud hole. We were there 42 days. Kept 24 men on the guns and lost 42 in the time, an average of one a day”. He used the word shocked for one man, which he described as “to be shell shocked, one is just in a daze until it wears off, if it ever does”.

January 14th

Sent to Eighth Brigade as runner. Slept in an old pit. Cold.

January 25th

Missed breakfast. Pimm, the HQ cook, gave me best dinner in France. Box from Aunt Edith.

January 26th, 1917

Box from Myrtle.

January 27th

Got paid. Made five trips from HQ to Battery.

January 28th

One trip to Battery. Two to Sainte-Catharines.

January 29th

Plum pudding for supper.

January 30th

Rode bicycle with dispatches to Hermaville. Started to snow. Through Louez, Eturn, Bray, Ecdivres, Aco. Anzin-Saint-Aubin.

Returned by Arras-St. Pol Road to Sainte-Catharines. Played out. Left bicycle behind a brick wall, kicked some snow over it, got it next day.

January 31st, 1917

Duffy, Bell and I got our lost kit bags. BHQ left of Arras and Lille Road in front of Sainte-Catharines.

February 1st

Trips to Battery until the 4th.

February 4th

Over to Eighth Infantry BHQ, with Mr. Case. One trip to Anzin to meet dispatch rider. Trips to Battery 'til February 8th.

February 8th

Walked to Mont-Saint-Eloi and on to to Ecurie to dentist.

February 9th

Battery moved to a new position back of Arian dump.

February 11th

Eighth HQ went out. Ninth took over. Not as good a cook as Pimm.

February 12th

Built a bivouac, Trips to Battery as usual until February 16th.

February 16th, 1917

Marched to Amettes to rest. Bennett, Berry and I rode mule train, to Maroeuil. Walked to Camblain l'Abbé.

Caught column. Marched all night. First experience with Captain Dick.

February 20th

Long hard march to Bully Grenay, through Ferfay, Camblain Châtelain, Houdain, Barlin, Hersin-Coupigny near Bully-les-Mines, and Sans-en-Gohelle near Liévin.

February 21st

Mounted orderly to wagon lines.

February 22nd

Rode little rat-tailed black to guns with orders, to Bully-Grenay, to 8th Brigade HQ.

Post card photo of the bombed out railway station at Bully Grenay, ca 1915.

(In the Canadian Corps reorganization which took effect on 20 June 1917, the 8th Brigade was transferred from 3rd Divisional Artillery to become the 8th Army Brigade C.F.A., commanded by LCol J.C. Stewart, DSO. It took the 32nd Battery from the 9th Brigade, and the 43rd (Howitzer) Battery from the 10th Brigade, completing its establishment with the 24th Battery, which had been organized in the field for that purpose. These gunners wore a green patch on their shoulders. (Col G.W.L. Nicholson CD, The Gunners of Canada, The History of the Royal Regiment of Canadian Artillery, Volume I 1534-1919, (McClelland and Stewart Limited, Toronto, 1967), pp. 291-292).

February 23rd, 1917

One trip, Forty-fifth rear at Hersin-Coupigny.

February 25th

On late trip to Hersin. Found 45th officers in Etaminez.

February 27th

Moved to Amettes. Had dinner in a French restaurant.

March 1st

Still at BHQ. Lots of bicycle riding.

March 5th

Two inches of snow. In to Lillers p.m. Fried eggs and chips.

March 6th

Returned to battery.

March 7th, 1917

Getting ready to move in the morning. George Haddock and I found a place and got double orders - eggs and baked beans.

March 8th

Long march to Guoy-Servins. Guns went in to Ablain-Saint-Nazaire.

(Robert Sennecke Photo)

Field-Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, Kaiser (Emperor) Wilhelm II, and General Erich Ludendorff Hindenburg, January, 1917.

As Walter arrived in France, Allied plans were underway for another assault against a German defensive position dug in on Vimy Ridge in North-West France. The Germans had successfully repelled all British and French attempts to secure it to date. The Germans had brought Field-Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and his Chief of Staff, General Erich Ludendorff (the real brains of the combination), from the Eastern Front to replace General Erich von Falkenhayn in this sector. “One of their first acts was to begin the construction of a strong defensive position (known as the Hindenburg Line), behind the River Somme. Rather than fight on the Somme a second time, the Germans then relinquished ground in the spring of 1917 and fell back to the new and shorter line to release 13 divisions for employment elsewhere.” [6]

The French, like the Germans, also brought in a new commander-in-chief in 1916. He was General Robert Nivelle, who had been responsible for the successful French counter-offensive at Verdun, and he had a grandiose plan for 1917. He intended to break through the German lines in one bold stroke. In Britain, Prime Minister Lloyd George had replaced Asquith, and, dissatisfied with General Haig's conduct of the Battle of the Somme, made him subordinate to the French general for the attack on Vimy Ridge.[7]

“By withdrawing to the Hindenburg Line in March 1917, the Germans disrupted Nivelle's plan and restricted the French thrust to a sector immediately south of the new Hindenburg defence system. In spite of this, Nivelle directed Haig to open a preliminary offensive in the Arras sector to draw German reserves away from the River Aisne, where the French planned to strike their main blow. Haig planned a double battle to help Nivelle. The Third British Army would mount an attack on an eight-mile long front, astride the River Scarpe, and on the adjoining four miles of front the Canadian Corps would assault Vimy Ridge. [8]

Walter recorded his participation in this assault as follows.

March 9th

Went up to guns. First good view of Vimy Ridge.

Notes. As I scanned through this portion of the diary, I noted that the terrain and battlefields were colourfully described. Souvenirs and living conditions were always of interest. One day he had gone up to a place near Vimy Ridge called “the Pimple” on a foggy morning to take a look at where the French and Germans had fought so desperately the first year of the war. The skeletons were still there, and he noted that there were several V-shaped shields made of oak and steel also still in place. These had been pushed in front of the men while they were crawling forward. The Pimple was under observation and when the fog lifted he didn't stop long. He remembered carrying a beautiful pair of French officer's boots, but after shaking the foot bones out of them, he didn't seem to care for them anymore. He also said that they never could seem to become attached to lice or dirty underclothes enough to regret their passing.

When asked about Vimy Ridge, the subject of “sandbag pudding” came up. It had snowed and rained for a couple of weeks after they had gotten to Vimy. Ammunition had to be packed over roads at night. Their bread rations were put into two sandbag lots slung over a saddle and tied on. The sandbag fuzz worked into the wet bread and it was all one loaf in the bag when they finally got it. Earlier, they had been given a few rations of plum and apple jam. The cook dumped the bread in a big boiler along with a couple of cans of milk and a quart pail of jam, stirred it up and gave them two ladles per ration. His friend Bert Bryan said he ate so much sand bag lint that he never had to wipe himself all the time he was at Vimy.

Rabbit stew brought out another “food” story. Australia shipped an order of frozen rabbits to the commissary as a treat for the soldiers. They were shipped frozen in crates of about two dozen. They had rounded them up in an enclosure, conked them with a club and crated them as they were. By the time they left cold storage until they reached the soldiers, they had thawed out and one could smell the G.S. wagon half a mile away. The cooks and helpers had to wear their gas masks to clean them and soak the carcasses in salt and water for at least 24 hours. He said “they didn't taste too bad if you held your breath”.

March 10th

Foggy day. Went on guard. On four hours. Off. Tramped up on the Pimple where French and Germans fought so desperately the first year of the war. Skeletons still there. Some interesting equipment. Several V-shaped shields made of oak and steel, that a man could push in front when crawling along.

March 12

Over to hospital corner in evening with a working party. Horses got bogged in shell holes. Out 'til 5:00 a.m.

March 14th, 1917

On ration party. Carried ammunition to gun position. Usual lot of night firing next three days.

March 18th

To baths in Ablain-Saint-Nazaire. Got a change of clothes at last. The lice were about ready to carry off the old ones.

March 20th

Out in storm with O'Brian to dump at Gouy-Servins. Usual action.

March 24th

Moved to plank road position in front of Mont-Saint-Eloi.

March 25th

Worked at gun pit. Bert Slack wounded at Ablain-Saint-Nazaire. Next three days lot of action. Built a gun pit as near splinter proof as possible. With available material, next few days built bunks in rear of gun pit. Signaler wounded by premature from battery in rear.

April 3rd, 1917

Sky full of planes all day. Lot of firing. Few whiz-bangs were falling short. Carried lot of ammunition.

(Author Photo)

German Great War Fokker D.VII, original War Trophy aircraft on display in the Brome County HistoricaL Museum, Knowlton, Quebec.

(Author Photo)

German Great War AEG IV, an original twin-engine bomber (the only one of its kind) on display in the Canada Air & Space Museum, Ottawa, Ontario.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3390977)

French soldiers examining Sopwith 1F.1 'Camel' (Serial No. E4389) of the RAF, which landed inside Canadian lines near Amiens, France, August 1918.

Sopwith 1F.1 Camel, RFC. (RAF Photo)

(Author Photo)

Sopwith 2F.1 Camel (Serial No. N8156), n the Canada Air & Space Museum, Ottawa, Ontario.

(Author Photo)

Sopwith Snipe replica (Serial No. E6938), on display in the Canada Air & Space Museum, Ottawa, Ontario.

(Author Photo)

Sopwith Triplane replica (Serial No. N6302), on display in the Calgary Aerospace Museum, Calgary, Alberta.

Walter spoke about the aircraft he saw this way:

“Our planes at that time were nearly all two wing. Through all of 1917 the English came over with Triplanes. They were slow, but at full speed would take altitude quickly giving the allies an advantage in the dogfights. The German ace Baron Von Richthofen's squadron was painted a bright red. Our planes had red, white and blue circles (like a target). The German (aircraft had a black cross). We could always tell the German planes by the sound of the motors. Before the Triplane the dogfights were all on our side of the line. After Baron Von Richthofen was brought down, the fighting was mostly on the other side. There were many mistakes made by aircraft, especially after nightfall.”

April 5th

On working party to OP. Saw infantry over on a raid behind our barrage.

April 6th

Two planes came down in flames up front.

(Author Photo)

.303-inch Ross Rifle, on display in the New Brunswick Military History Museum, 5 CDSB Gagetown, New Brunswick.

(Author Photo)

.303-inch Lee-Enfield Rifle, on display in the New Brunswick Military History Museum, 5 CDSB Gagetown, New Brunswick.

(Author Photo)

.303-inch Lewis Machinegun, on display in the New Brunswick Military History Museum, 5 CDSB Gagetown, New Brunswick.

Gramp told me about some of the weapons he trained with, and spoke about his attempts to fire back at German aircraft that attacked them:

“All rifle training in the army was with the .303 Ross and .303 Lee Enfield rifles. Also had a course in the Lewis .303 machine-gun. I blazed away at lone flying German planes when they flew low. I had my gun pinned in the top of a post and when Fritz flew over us, everybody ducked but Estabrooks. They often strafed our 18-pounder. The 18-pounder was 3.03 bore compared with the .303 rifle. I had training on old muzzle loader cannons at Sussex back in 1905, and from 1906 to 1914 had two weeks training at Sussex camp, and competition shooting at Petawawa, taking about a week away from home. All 18 pounders were equipped with a #7 dial sight.”

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4474053)

QF 18-pounder Field Gun, 15 Apr 1915, CFA.

(Author Photo)

Ordnance QF 18-pounder Gun on display in the Canadian War Museum, Ottawa, Ontario.

April 7th

Lot of firing. Fritz put over shell gas in the evening.

April 8th

Shelled quite a bit. Len Smith wounded -- gun pit across (yrack?) hit twice. Stretcher-bearers busy. Getting ready for big strafe.

Battle of Vimy Ridge, 9-12 April 1917

The Battle of Vimy Ridge was a military engagement fought primarily as part of the Battle of Arras, in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region of France, during the First World War. The main combatants were the Canadian Corps, of four divisions, against three divisions of the German Sixth Army. The battle, which took place from 9 to 12 April 1917, was part of the opening phase of the British-led Battle of Arras, a diversionary attack for the French Nivelle Offensive.

The objective of the Canadian Corps was to take control of the German-held high ground along an escarpment at the northernmost end of the Arras Offensive. This would ensure that the southern flank could advance without suffering German enfilade fire. Supported by a creeping barrage, the Canadian Corps captured most of the ridge during the first day of the attack. The town of Thélus fell during the second day of the attack, as did the crest of the ridge once the Canadian Corps overcame a salient against considerable German resistance. The final objective, a fortified knoll located outside the village of Givenchy-en-Gohelle, fell to the Canadian Corps on 12 April. The German forces then retreated to the Oppy–Méricourt line.

Historians attribute the success of the Canadian Corps in capturing the ridge to a mixture of technical and tactical innovation, meticulous planning, powerful artillery support and extensive training, as well as the failure of the German Sixth Army to properly apply the new German defensive doctrine. The battle was the first occasion when all four divisions of the Canadian Expeditionary Force participated in a battle together and it was made a symbol of Canadian national achievement and sacrifice. A 100-hectare (250-acre) portion of the former battleground serves as a memorial park and Hill 175 is the site of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial.

April 9th

Big strafe started 5:00 a.m. Took turn at gun laying. Prisoners started coming along, herded by one of our walking wounded. Back to Mont-Saint-Eloi. Met Bill Dawson. Went on guard that night.

April 10th, 1917

Back to dressing station to meet brigade runner. Battery started moving ahead.

April 11th

Moved ahead to Bethune Road left of Neuville-Saint-Vaast. Dug in lot of ammunition left in gun pits. We got hold of two small flat cars. Used them 'til dark. By this time, about six inches of snow had fallen. I was left to guard the cars. A couple of left section boys to guard the ammunition. We upset the cars in shell holes. Piled snow over them. Moved the ammunition into the least damaged gun pit and took our shift four on and four sleep, until we were relieved by working party next morning.

April 12th

B. Sub gun went to ordnance. Lieutenant Clark sent me to wagons lines at Guoy-Servins about eight miles each way through snow, slush and mud. I did not need rocking that night.

April 13th

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3522013)

78th Battalion men leaving Y.M.C.A. Dugout near front line, September, 1917.

Enemy out of range. Moved ammunition all day. YMCA set up field canteen at Neuville-Saint-Vaast. Had feed -- peaches and biscuits.

April 14th, 1917

Rested part of the day. Packed up to cross No Man's land and left position. To cross No Man's land and the ridge before morning, we advanced by way of Ecurie.

April 15th

Crossed the battlefield of Vimy Ridge. The road had been so badly torn up by our shelling, the holes filled with mud and slush, that we had to relay the guns ahead for short distances with six teams. The dead had not yet been buried. Reached Vimy 12:00 noon. Took up position southern end of town. Lived in an old house while digging in. Wattie Waddell wounded.

Walter described Vimy Ridge to me as,

“Having an easy slope from the Lorches valley on our side, fairly steep on the eastern side, looked like an ordinary piece of farming country at first look. The German front lines and ours were on a slight valley on the western side. Our guns ploughed the whole western side and top over to the village of Vimy on the eastern side”.

April 16th

Again in action. Sgt. O'Neal and I had a close call from a 5.9. Robert Deware killed repairing wire front of Vimy. George Haddock and I carried him back to gun position. Burial service conducted by Captain Dick. Later moved to cemetery. Harry Bryan shocked in front of B. Sub gun. Morrison and Wickens got boxes of candy.

April 17th, 1917

To 22nd. Shelling and being shelled. Gas over every night. Fritz plane strafed us. Blazed away at him with rifle. Got struck on head with a chunk of mud. Morrison got a nasty scratch.

April 23rd

Up 4:00 AM. Put over 116 rounds. Gas thick all afternoon.

April 24th

Up to WIT. At railroad. On telephone most of the night.

April 25th

Plane came down in flames. Went back to canteen west of Neuville-Saint-Vaast. Bought a sand bag of chocolate biscuits, canned fruit. The first week in Vimy, rations were packed over the ridge at night on horse or mule back. The bread was put in two sandbags and thrown across a saddle. It rained every night and the drivers came down over the hill on the run. The bread got wet and was a sodden mass on arrival - the jute fibre from the bags well mixed in. The cook dumped it in a big boiler, added a little water and a half pail of jam. We were soon fed up on sandbag pudding and the little extra from the canteen was appreciated almost as much as a box from home.

April 26th, 1917

Next four days ... give and take. We were gassed about every night and had to retaliate while wearing gas masks. First division infantry had a rugged time up front. Heavy casualties reported. Reid gassed night of the 29th. Feed from canteen night of 30th.

May 1st

Had to stand to, stand by for nearly five hours with masks. Lieut. Pete Cornel ordered a roll call parade seven o'clock. I was late getting on parade. Pete stopped in front of me. “Estabrooks, did you shave this morning?” “No sir.” “Did you wash this morning?” “No sir.” “Sergeant Major, see if you can't find something for these two boys to do.” He had caught another in the left section. (“Just what I need, sir! To clean up the ammunition that did not explode in that pit that was blown up!”)

May 2nd

Haddock and I took Jimmie Morrison to railhead dressing station, sick. He never got back to 32nd. He was a good soldier, and could sing Lauder's songs a little better than Harry.

May 3rd

Lots of night firing. Gas about every evening. Fixed better emplacements for the guns. Carried steel rails and oak ties to make our dugout splinter proof. Signalers shelled out of their dugout under an old house, night of the 10th. C Sub. Shelled out of their dugout, night of the 11th. Two signalers wounded night of 13th. Went back to wagon lines.

May 14th, 1917

Out herding horses back of Berthonval Wood. E Sub gun hit several wounded.

May 15th

F Sub gun put out of action. Duties around lines. A lot of Carleton County boys looked me up. To dentist, 19th.

May 20th

Sent back to guns. Chris Armstrong and I tramped boldly over the ridge in daylight. Fritz tried us with a whiz-bang. I was nearer the shell hole. Chris claimed he made 14 feet from the time we felt the shell coming 'till we were into the shell hole, and the whiz bang burst a few yards beyond us.

May 21st

D Sub dugout blown up -- interrupting a 'Penny Ante' poker game. Dugan stayed long enough to show a pair of deuces and picked up the 2, 5, 10 centime and half franc piece on the blanket.

May 22nd

Feeling rotten but kept going the next week. Went down the line. Must have had a touch of trench fever.

May 31st, 1917

I looked up the Tapley boys. Rideout, McLeod, Lutes, McFarlane, Cronkite, Bingham, Kidney brothers, Staires and Monteith from old 65th.

June 1st

Went up the line. Tony Gibbs killed that night.

June 2nd

Got ready for strafe. Stood to until 2:00 a.m. Went back to wagon lines. Herded mules. Went to dentist. Helped get ready for tournament on the 9th. 32nd made good showing.

June 9th

George Haddock wounded in B Sub gun pit.

June 14th

Worked on show wagon. Went up the line at night.

June 15th

Strafe in the night. Played checkers with S. M. Donaldson. Next week we strafed the Bosche and he strafed us.

June 22nd

Greg sent to hospital sick.

June 24th, 1917

Whiz-bang bounced off E Sub dugout. 33rd and 45th shelled. (9th Brigade under 3rd Division).

June 25th

Inspection by General Mitchell. B gun out of action. SOS

June 27th

Limber gunner. Took gun (10 km West) to Ordinance at Villers-au-Bois. About a dozen guns in line up ahead of me. Kept gun coming ahead in line, and worked in shops with Joe McMaster until I returned with it to battery. Now out on rest at Berthonval farm.

I asked him about the task of working as a limber gunner, and he proceeded to describe his duties in this capacity as follows:

“The limber gunner services the gun. He takes charge of loading kits and equipment, so the limber is excused other fatigues. When his battery was loaded at the train station, they were loaded up on flat and box cars, flats for the guns and box cars for the horses, six horses in a car”.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3395370)

Canadian Gunners loading their limbers from an ammunition dump, May 1918.

July 9th

After two bad days in position embankment, left front of Vimy station.

Some time during this period, Walter observed King George and several members from the Labour Party walking over the ridge from La Targett in steel hats and civilian clothes.

“I was on orderly duty, passed through them going down and when they were coming back everyone one of them had some kind of a souvenir, an old rifle barrel, empty shell case etc. I also heard Sir Robert Borden at Lincquiser on Canadian Sports Day. It would take too long to tell it here”.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3642847)

18-pounder Field Guns, being examined by Canada's Prime Minister, Sir Robert Borden, Bramshot, UK, Apr 1917.

Sir Robert Laird Borden, GCMG, PC, KC, (26 June 1854 – 10 June 1937) was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the eighth Prime Minister of Canada, in office from 1911 to 1920. He is best known for his leadership of Canada during the First World War.

(Historical Section of the General Staff, Department of National Defence Photo)

Map, Battle of Vimy Ridge, 9-12 April 1917. Canadian War Museum file CWM19980056-280 & Nicholson, G. W. L. 1962. Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War: Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914-1919. Queens Printer and Controller of Stationary, Ottawa, Canada.

Vimy Ridge

The official war records indicate that the Canadian task to assault Vimy Ridge “was formidable. Vimy Ridge reared out of the plain like a whale, humped in the north, then tapering off gradually until it finally disappeared in the Scarpe valley in front of Arras. The highest points, Hills 145 and 135, dominated the surrounding country, and the irregular slopes of the ridge favoured the enemy. The western slope, up which the Canadians would attack, though gentle, was very open and could easily be swept by fire. The reverse slope, on the contrary, was almost precipitous and well wooded, providing excellent shelter for reserves and guns.” [9]

“During the previous two years these natural advantages had been greatly enhanced by the Germans who had fortified the ridge with successive lines of well-wired trenches, deep dugouts with interconnecting tunnels, and concrete strongpoints. Vimy was a keystone in the enemy's western wall, for hot only did it protect a vital mining and industrial district of France, then in full production for Germany, but it also covered the junction of the Hindenburg Line with the defences running south from the English Channel. It would be impossible for the British to hold ground in the Arras sector in Vimy Ridge remained in German hands.” [10] The Canadians would have a difficult task to achieve in capturing it.

“Sir Julian Byng's planning was very thorough. All four Canadian divisions would attack simultaneously in line, with the 4th, the 3rd, 2nd and 1st from north to south. In each case the final objective was the far side of the ridge. Each division came into line on the front assigned to it so that the men could have a good look at the ground. Then they were withdrawn again to rehearse the attack over a full-scale model on which German trenches and strongpoints, kept up to date from ground reconnaissance and air observers' reports, were clearly marked. Training was intensive and realistic, and constant repetition made every man familiar with the ground and with the tactics that would be expected of him in the real attack.”[11]

At night “tunneling companies dug miles of subways through which troops could move to and from the front line in safety. Chambers for brigade and battalion headquarters, dressing stations for the wounded and great caves for stores were carved in the walls of the tunnels; all had piped water and electric light. Roads and light railways were built in the Canadian forward areas to bring up ammunition, engineer stores and rations. The signalers were no less busy. To existing telephone circuits they added 21 miles of cable buried seven feet deep to protect it from shelling and installed more than 60 miles of unburied cable along the tunnels and trenches.” [12]

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3405811)

Canadian Signalers repairing wire in communication trench. February 1918.

Enough artillery was provided to Byng to give twice the density of fire that had been available “at the Somme. A new fuse, designed to burst above the ground, would cut the German wire for the attacking infantry. Great emphasis was placed on “counter-battery” fire to locate and destroy the enemy's guns just before the attack. Finally, and most importantly, a deception plan was designed to ensure that there would be no noticeable change in artillery activity, even on the day of the assault. The preliminary bombardment would last several days, and be maintained right up to zero hour.” [13]

“Easter Monday 09 April 1917, was chosen as the day of the attack. The preparatory bombardment began on 20 March, but to conceal the full extent of the massive artillery support available, only half the guns were used during the first two weeks.” On 02 April a weeklong pounding of the German positions began. “On the night of 08 April, the infantry moved forward through gaps in the wire to occupy jumping-off positions in No Man's Land. The moon was just past full and partly clouded over,” screening the tense lines of waiting men. In front of them shells burst along the dark ridgeline as towards morning the weather turned bitterly cold. Frost covered the torn-up ground.[14]

“Zero hour was at half-past five. At about four, a raw wind blew up, darkening the sky with clouds and covering the Canadians' backs with snow. The attack began exactly on time in the dim half-light, while slanting sleet blew in the faces of the Germans. 15,000 Canadians surged forward in the first wave, closely following the line of the artillery barrage which rolled towards the ridge in precisely lifted increments of 100 yards.” Two other follow-on waves of infantry followed. [15]

“The first wave found the defences smashed and the wire effectively cut. Only a few sentries were above ground in the battered front-line trenches; they were quickly dispatched, and guards were posted at dugout entrances until the mop up wave arrived. The lead troops swept on to the second line where, although many Germans were trapped below ground, there was some hand-to-hand fighting before the attackers again moved forward.”[16]

German distress rockets were launched into the grim morning sky, but the Canadian counter-battery fire had already disabled much of their artillery. Much of the fire from the few guns the Germans were able to bring to bear fell behind the attacking troops. Gradually however, the hostile fire began to increase, thinning the ranks of supporting units. “Beyond the second line, the infantry encountered determined opposition from well concealed snipers and concrete machine-gun posts, and losses began to mount. On the lower slopes and across what had been No Man's Land, columns of prisoners were collected and marched to the Canadian rear area under escort, while stretcher-bearers carried the wounded, messengers moved through the lines, and supporting troops brought up mortars, machine-guns, picks, shovels, ammunition, water and grenades for the task of consolidation.” [17]

“The Canadians reached the crest shortly before eight o'clock in the morning, but hard fighting still lay ahead. On the steep reverse slope the enemy opened up with machine-guns and field guns at pointblank range. In spite of this, the troops plunged downhill in a raging blizzard, overran the batteries, and seized the sheltering woods. By early afternoon most of the Corps final objectives had been taken.”[18]

The highest point on the ridge, Hill 145, still held out until the afternoon of the 10th. After two separate attacks, the summit was finally cleared and the ground captured on the far side. This placed the four-mile length of Vimy Ridge entirely in Canadian hands. Artillery still had to be brought forward however, to smash any counter-attacks that might develop and to capture two adjacent features known as “the Pimple” and the Lorette Spur.[19]

“The Battle of Vimy Ridge had been a striking success, and by far the greatest British victory of the war up to that time. The Canadian Corps had overcome one of the most formidable German defensive positions on the Western Front, and Ludendorff, who celebrated his 52nd birthday on this famous 9th of April, confessed that he was “deeply depressed.” The Canadians captured some 4,000 prisoners, as well as 54 guns, 104 trench mortars and 124 machine-guns, at a cost of 3,598 fatal casualties. The Canadian memorial presently standing on Vimy Ridge was ceded to Canada by France in perpetuity. It is sited on top of Hill 145, the highest point of Vimy Ridge.”[20]

Late in April, the Canadians fought through the area of Arras, capturing Arleux and Fresnoy in some of the hardest and most unrewarding fighting of the war. The French Government replaced Nivelle with General Henri-Philippe Pétain on 15 May 1917, and this freed General Haig to launch an offensive of his own in Flanders.[21]

Following their experience at Vimy, Walter’s gun detachment was sent on a short but well deserved rest. His diary entries for the period read as follows:

July 16th

Still on rest.

July 20th

Sports day. Ball game, 22nd and 24th. (9 to 7). Painted guns and wagons a design to camouflage and confuse photography from the air. Rabbit stew supper, 25th.

July 31st, 1917

Big push from Lens to the coast. Six weeks of rain and mud. Usual wagon line fatigues. Getting ready for inspection, etc. Stayed out of line all of August to August 25th.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3624530)

Royal Canadian Artillery, 18-pounder gun emplacements in the vicinity of Lens, France, Sep 1917.

End of Part I, Part II is posted on a separate pagech Council in 1933; Commander, First Canadian Army in 1939; and, Minister of National Defense in 1944.