Royal Canadian Air Force Women’s Division (RCAF WD)

(Yousuf Karsh Photo, 14 Nov 1942)

Wing Officer Willa Walker, OBE, Commander, RCAF Women’s Division.

Willa Walker rose rapidly through the ranks in 1941 to become head of the newly-formed RCAF Women’s Division. Only 28 years old, grieving the recent death of her baby son, her husband locked away in a German prison camp, she rose to the challenge with courage and dignity, breaking down barriers for future generations of women in uniform.

Elements of her story are presented on this page from an article written by Elinor Florence, who wrote a tribute to her.

Wilhelmina Magee was born in Montreal on 3 April 1913, one of four children of bank president Allan Magee and the former Madeline Smith of Saint John, New Brunswick. The Magees lived in Montreal, but the children enjoyed spending summers at the Smith family’s rental cottage in Saint Andrews, New Brunswick. Willa, as she preferred to be called, received an excellent education at a private school for girls called The Study, and developed a keen social conscience. She was an early backer of the famous Canadian doctor, Norman Bethune, who became a giant figure in the Chinese civil war. Willa also enjoyed downhill and cross-country skiing at Saint-Sauveur, Quebec, during the era when the legendary “Jackrabbit” Johannsen was introducing cross-country skiing to Canada. (A fitness pioneer, Jackrabbit skied until his death at the age of 111 and is buried at Saint-Sauveur.)

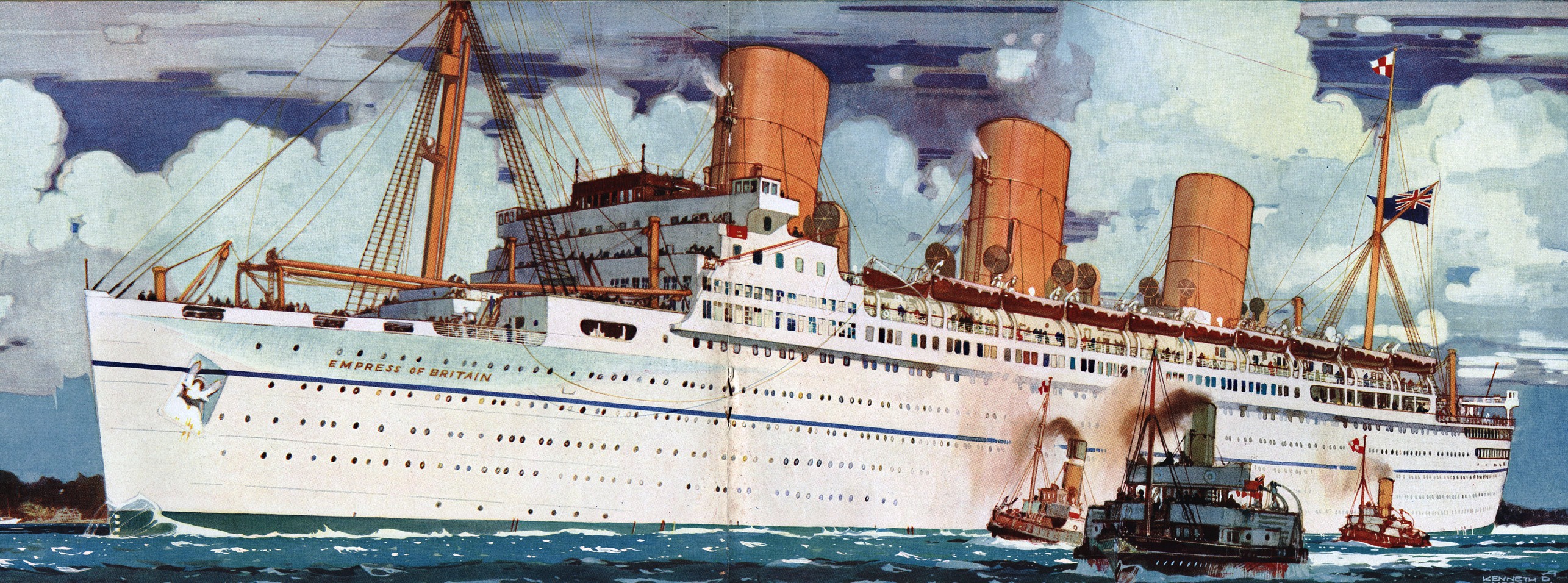

After finishing school, Willa travelled to Paris to study French language and culture. Upon her return to Canada in 1933, when she was still only 20 years old, this plucky young woman worked her way around the world as postmistress on Canadian Pacific’s famous Empress of Britain ocean liner, shown on this travel poster.

RMS Empress of Britain.

Back in Montreal, Willa was employed by a news agency, accompanying the photographers who took pictures of local debutantes and celebrities. Hearing that Sir Herbert Marler had been appointed as Canadian minister to Washington, D.C., Willa offered herself as social secretary to his wife Lady Beatrice Marler, and spent the next two years in Washington with the Marlers before returning to Canada. In 1939, Willa was invited to a party at Rideau Hall in Ottawa, residence of the Canadian Governor-General, and there she met a young Scottish captain in the British Black Watch 51st Highland Division, named David Walker. David was serving as aide-de-camp to Governor-General Lord Tweedsmuir, the novelist John Buchan. The couple’s first meeting was far from promising – Willa asked David for a sherry, but he brought her a stiff Scotch instead! However, sparks flew between the attractive young couple, and after a whirlwind courtship, they married on July 27, 1939. Only a few days after their honeymoon in David’s native Scotland, war was declared and he rejoined his division. This photo shows a happy David and Willa on their honeymoon.

When David went to war with his regiment in France in 1940, Willa stayed with David’s parents at their home in Cupar, south of Dundee, not far from Saint Andrews in Scotland. Shortly before the evacuation of Allied troops at Dunkirk in June 1940, David’s entire division was captured at Saint-Valery in Normandy. David spent the next five years in a prison camp. He managed to escape three times, but was always recaptured. Eventually, he was sent to the infamous Colditz Castle in Germany, a fortress for incorrigible inmates who had repeatedly escaped from other camps. It wasn’t until after his capture that Willa discovered she was pregnant. She returned to Canada for the birth of her son Patrick in November 1940, but tragically, he died of crib death in February 1941 at the age of three months. His loss was a lifelong sorrow for Willa, and David never saw his young son.

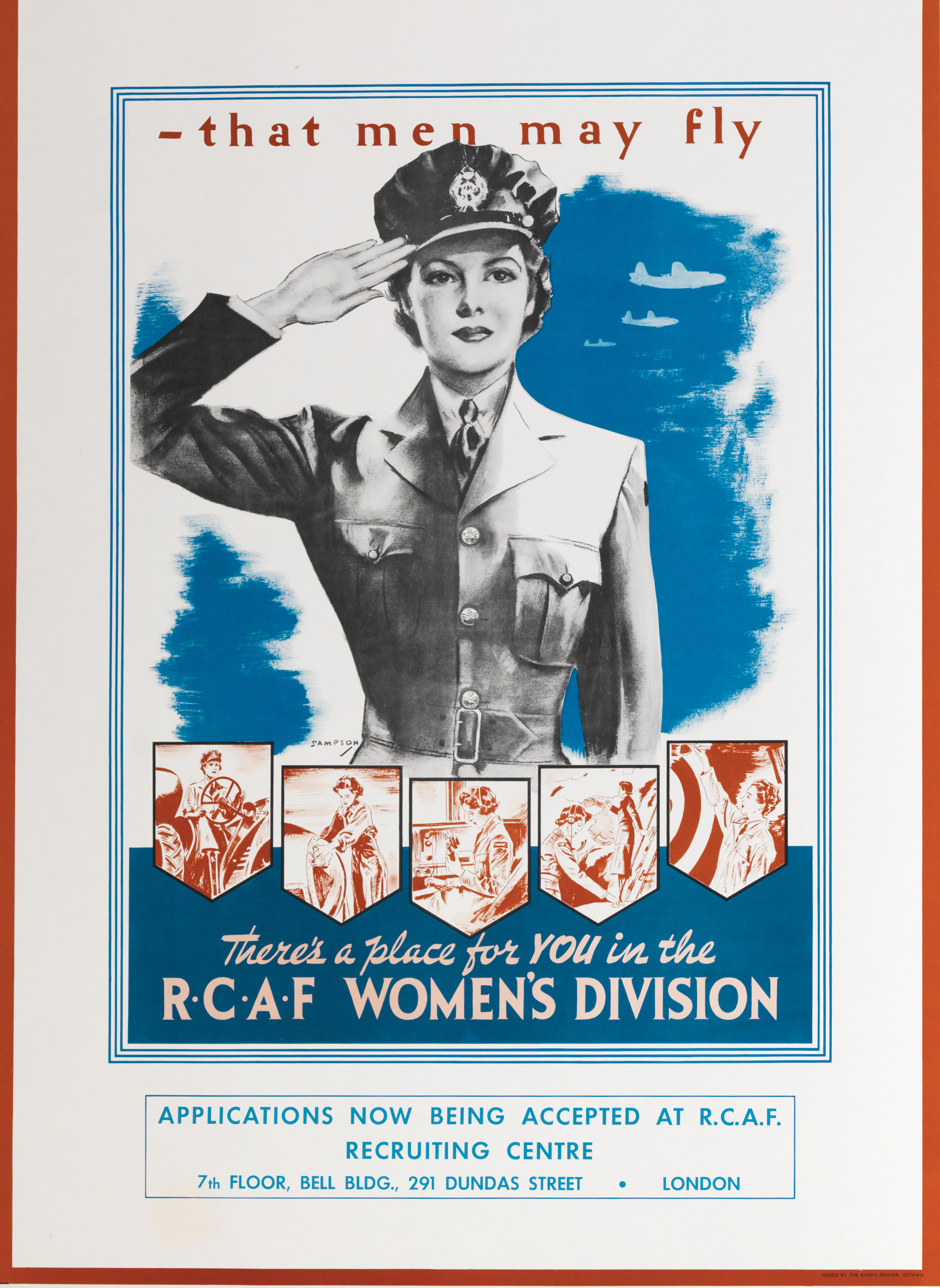

It wasn’t until July 1941 that Parliament finally yielded to public pressure and passed an Order-in-Council allowing women to enlist, and the RCAF immediately formed a branch called the Women’s Division with the motto: “We Serve That Men May Fly.”

With her baby gone and her husband in prison, Willa decided to join the war effort herself. In October 1941 she graduated with the first group of air force recruits, and achieved the highest marks in officer training. Three months later, in January 1942, she was placed in charge of the new female recruits in Canada, all of whom entered Number 7 Manning Depot in Rockcliffe, Ontario, for basic training. In February 1943 Willa was promoted to commanding officer of the Women’s Division in Canada. In doing so, she replaced Kathleen Oonah Walker (no relation), another esteemed female officer who departed for England to become head of the Women’s Division overseas. Both women were given the rank of Wing Officer, and from then on Willa became known among the ranks as “The Wing.”

(DND Photo)

Willa Walker, left, and Kathleen Walker, right, March 1943.

Willa was a natural-born leader. She was responsible not only for setting up training depots all over Canada, but for the overall discipline and efficiency of the Women’s Division. It was also her duty to urge more women to enlist, and no doubt her enthusiasm convinced many young women to follow in her footsteps. As commanding officer of all the airwomen in Canada, Willa’s portrait was taken by the famous Canadian photographer Yousuf Karsh. He took the formal photograph of her in uniform seated at her desk. At the same time, he also took this less formal portrait of Willa in a tweed jacket. This is the photograph that she sent to David in prison, and one that he cherished during his long years of captivity.

(Yousuf Karsh Photo)

At the time, many Canadians believed that women didn’t belong in uniform, that they should tend the home fires instead – knitting socks, rolling bandages, and growing Victory gardens. They feared that a woman’s reputation would suffer if she were away from her parents’ watchful eyes. It was Willa’s job to persuade them otherwise. For the next couple of years she criss-crossed the country by land and air, speaking to groups and organizations, even church congregations, in an effort to change the public perception of women in uniform. Recruiting posters like this one were seen everywhere.

In May 1943 Willa undertook an exhaustive trip across Western Canada, visiting 33 air bases between Winnipeg and Vancouver Island in five weeks, recruiting young women and meeting as many of their parents as possible. “You would consider it the right thing for your sons to do, and you should also feel that it is the only right course for your daughters,” she urged.

One of her most persuasive arguments was that air force life was good training for future homemakers! “Life in the air force is a wonderful background for marriage,” she said. “A marriage is going to mean so much more, because of the experience the man and woman have shared together in uniform. A girl who has been in the service will be able to understand her husband better – because she’ll know what he’s been through.” Canadian women would be better citizens after a period of duty, she said. “No one need fear that these women will never be able to settle down comfortably in their homes during peace time. They will, gratefully, but they will be better people – they will be more adaptable and have a better understanding. They will have benefitted greatly from a little discipline!” Most women, she explained, join the services for intensely patriotic reasons. Some have lost husbands or fathers or brothers, and are determined to take their places. “They aren’t looking for glamour,” she said. “They want it to be hard. They want to experience to some extent the life that their relatives had.”

On this tour, Willa was accompanied by another reputable officer, Jean Flatt Davey, the first female doctor in its Medical Division. Women in the air force were healthier than average, the two women explained, because they received good food, plenty of exercise, and excellent medical care.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4674254)

RCAF Women’s Division Personnel, Jean Flatt Davey and Willa Walker are seen third and fourth from the left, ca 1944.

Willa also emphasized the training that women received in forty different trades, including meteorologists, mechanics, wireless operators, and operational clerks. Although the women received only two-thirds as much pay as the men, female veterans would receive the same benefits after the war as male veterans, including pensions and the opportunity for further education. Willa was asked repeatedly by eager young recruits across the country when women would be sent overseas, but she was quick to point out that they were badly needed here on Canadian air bases. (Only about 2,000 of the 17,000 women in the air force were fortunate enough to be sent overseas in wartime. Willa went on to visit all the air bases in Eastern Command, and even travelled to the Dominion of Newfoundland, at that time a separate country.

(DND Photo)

Wing Officer Willa Walker seated at her desk, She is wearing her plain gold wedding band on her left hand, and a signet ring on her right hand. Airwomen were restricted as to the number and items of jewellery they were allowed to wear while in uniform.

Interviewed by newspapers from coast to coast, some male reporters didn’t quite know how to describe the impressive officer. One reporter wrote: “Mrs. Walker is of average height, very slim, with sparkling brown eyes, brown hair, and looks very young for the very responsible position which she holds.” It was still very much a man’s world, but privately, Willa waged a war for women’s equality. For example, at all the training depots, the officers’ mess, or dining hall, was reserved for men only, so Willa was not allowed to eat with the male officers. Frustrated by this regulation, one day Willa ordered her driver to park in front of the officers’ mess. In sub-zero temperatures, she sat inside the vehicle during a snowstorm, eating her cold crackers, until the male officers were so ashamed that they invited her inside. Across the country, women officers let out a cheer, as they were never again prevented from entering the officers’ mess!

It was another proud moment for Willa when the head of the British Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, after which the Canadian branch was modelled, visited Canada on an inspection tour and pronounced the women’s performance as “absolutely first class.” “The thing that has impressed me is their enthusiasm – their cheerful, keen attitude to do the job they are doing. People still don’t realize just how colossal it is,” said Air Chief Commandant Katherine Trefusis Forbes. In November 1943, Willa accepted a solid gold cup on behalf of the Women’s Division, a gift from the British Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, presented by Her Royal Highness Princess Alice, Duchess of Gloucester.

(DND Photo)

This photo shows Willa, centre, chatting with Princess Alice on the right, the Honorary Air Commandant of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, at a garden party at Government House in Ottawa in 1943.

For her war work, Willa was made a Member of the Order of the British Empire in London, England, in January 1944, presented by Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother.

(DND Photo)

This photo shows Willa wearing her decoration, flanked by her proud parents Madeline and Lieutenant-Colonel Allan Magee.

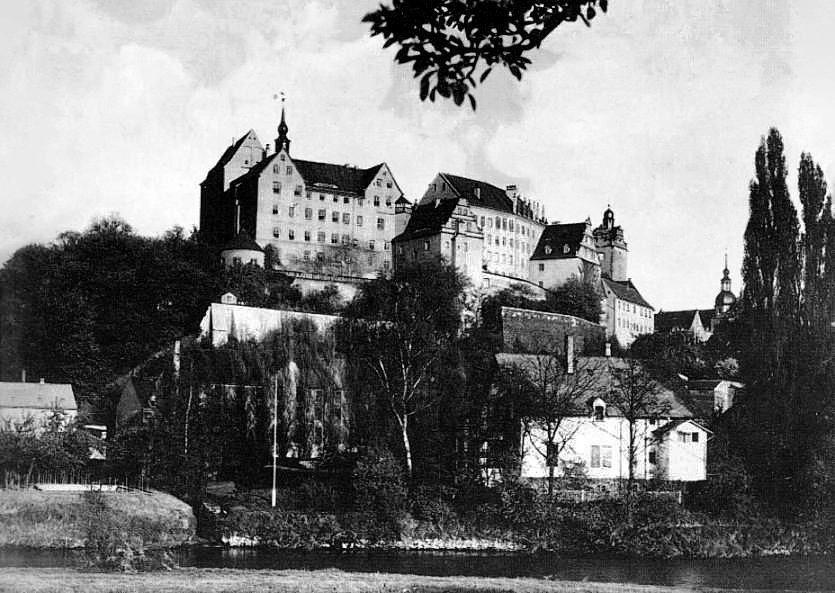

During the long years that David was in prison, Willa never gave up hope that he might escape. She came up with a code for communicating important news in seemingly innocent letters to her husband, which passed undetected by both the Canadian and German censors. She also managed to smuggle escape maps to David in the soles of a pair of shoes contained in a Red Cross package. This time, Canadian military officers intercepted the package and found the maps. At first, they admonished her for her foolhardiness – but the ingeniousness of the scheme appealed to them, so they repacked the shoes and sent off the package. Unfortunately nobody escaped from Colditz Castle, not even David.

(US Army Photo)

Castle Colditz (Schloss Colditz), April, 1945. This Renaissance castle stands in the town of Colditz near Leipzig, Germany. The castle was the site of officer prison camp 4C (Oflag IV-C), a Second World War prisoner-of-war camp operated by the Wehrmacht, for Allied officers who had become security or escape risks or who were regarded as particularly dangerous. While the camp was home to prisoners of war from many different countries, including Poland, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Canada, in May 1943 Wehrmacht High Command decided to house only British and American officers.

As the end of the war approached, women were no longer needed in the armed forces, and they began to receive their discharges. Willa resigned her post in October 1944 after three years of service, to await the return of her husband. It wasn’t until May 1945 that the war finally ended and they were reunited.

Some 17,000 women served in the RCAF Women’s Division following its creation in 1941, working in both traditional and non-traditional trades. Another 4,480 women served as nursing sisters. The RCAF was the first service to recruit women during the war, and the last to release them, with the final woman being discharged by March 1947. RCAF nurses, however, continued to serve. After the war, it was announced that there would be no Women’s Division in the permanent air force.

Six years later, in 1951, the air force began accepting women back into its regular ranks.

(DND Photo)

Airwoman, control tower, 3 (Fighter) Wing, RCAF Station Zweibrucken, Germany, 15 June 1954.

The RCAF was the first of the three services to recreate a women’s organization during the post-war period. In 1951, the Canadian government announced that women would be recruited into the RCAF because it needed more personnel due to the construction of three radar lines across the country: the Distant Early Warning Line, the Mid-Canada line and the Pinetree line. On 3 July 1951, the first 80 enlisted women arrived for basic training at St. Jean, Quebec.

(DND Archives Photo)

RCAF Airwomen undergo training on radar scopes at the Radar and Communication School, RCAF Station Clinton, Ontario.

(DND Archives Photo)

Five airwomen model RCAF uniforms at RCAF Station Aylmer, Ontario, 20 June 1952.

(DND Photo)

Canada’s first female fighter pilots, Capt Jane Foster (left) and Capt Deanna (Dee) Brasseur, posing in front of a Canadair CF-116 Freedom Fighter in 1988. Currently 19 percent of serving RCAF members are female. 23 women have risen to the rank of General or Flag Officer in the Canadian Forces.

Postscript

Willa and David Walker couple settled briefly in Scotland, where their son Giles was born. The young family then travelled to India, where David served as chief of staff to Lord Archibald Wavell and, subsequently, to Lord Louis Mountbatten. The final years of British rule in India were marked by tremendous bloodshed and turmoil. After Willa witnessed street demonstrations in support of Mahatma Gandhi, she became a great believer in his non-violent campaign for Indian self-rule, which was finally achieved in 1947. That year, the Walkers returned to Scotland, where David retired with the rank of Major, and their son Barclay was born. The following year, the Walkers returned to Canada and settled in Saint Andrews, New Brunswick, a lovely seaside town on the south coast where Willa had spent many happy summers as a child. There, two more sons were born, David and Julian.

David Walker twice received the Governor-General’s Award in Canada for Literary Merit, for his 1952 novel about a prisoner-of-war camp titled The Pillar, and for his novel Digby in 1953. As well as being an accomplished writer, David was an ardent conservationist, and one of the founding members of the Conservation Council of New Brunswick. He was made a Member of the Order of Canada in 1987. After his death from congestive heart failure in 1992, the Walker family established the David H. Walker Prize in Creative Writing at the University of New Brunswick in his memory.

Willa wrote a popular book about her beloved town titled Summers in Saint Andrews: Canada’s Idyllic Seaside Retreat, available on Amazon. Willa Magee Walker died in 2010 at the age of 97. On 16 June 2018, this park in Rockcliffe, Ontario was named and dedicated in her honour.

If you would like to see a more extensive outline of Wing Officer Willa Walker’s story, Elinor Florence keeps an excellent web page here:

https://www.elinorflorence.com/blog/rcaf-willa-walker/

She also posts to a wonderful page on RCAF Women here:

https://www.elinorflorence.com/blog/rcaf-women/

Elinor Florence has written a fact-based novel titled Bird’s Eye View, featuring the story of a young Canadian woman who joins the RCAF in the Second World War, and serves as an interpreter of aerial photographs. Named a Globe & Mail bestseller, Bird’s Eye View is available on Amazon and through all bookstores.

For more info about the book:

www.elinorflorence.com/birdseyeview

A very famous RAF Air Photo Interpreter, Constance Babington-Smith, was one of our heroines! Elinor drew heavily on Constance Babington-Smith’s autobiography when writing her book and thanked her in her author notes.

Here’s the blog post she wrote about her: www.elinorflorence.com/blog/babington-smith