Canadian Corps of Guides

Corp of Guides Officer’s cap badge with silver true and magnetic north arrows in a gold wreath, ca. 1901. These symbols were integrated into the King’s Crown cap badge in 1942, the Queen’s Crown cap badge in 1952 and the present day Intelligence Branch cap badge from 1982.

The Corps of Guides was created in the Canadian Army on 1 April 1903. Under the new structure, a District Intelligence Officer responsible to Director General of Military Intelligence (DGMI) was appointed to oversee Corps of Guides units established in each of Canada’s twelve Military Districts. The first DGMI, Lieutenant-Colonel W.A.C. Denny, had a very small staff overseeing information collection and mapping, and approximately 185 militia officers serving the Canadian Corps of Guides.

(Clive Law Photo)

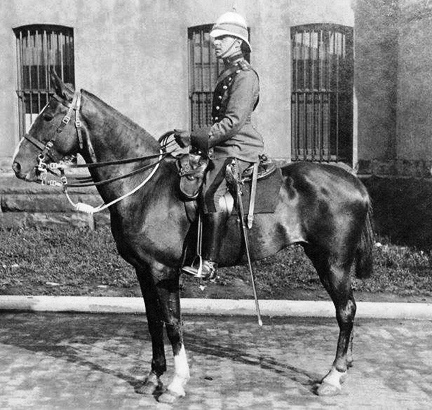

Corps of Guides Captain Cyril Tweedale.

Canadian Corps of Guides

Lieutenant-Colonel Victor Brereton Rivers, a former officer cadet at the Royal Military College of Canada was one of the first of a small band of officers serving in an organization that was in effect the forerunner of Canadian Forces Intelligence Branch as it is known today.[2] He carried out the necessary staff work which led to the formation of the “Canadian Corps of Guides” as authorized by “General Order 61 of 01 April 1903.” [3] This Order directed that at each of the 12 Military districts across Canada there would be a District Intelligence Officer (DIO) whose duties included command of the Corps of Guides in his District.

The Corps of Guides (C of G) was a mounted corps of non-permanent Militia with precedence immediately following the Canadian. The officers, NCOs, and men were appointed individually to the headquarters staffs of various commands and districts to carry out Intelligence duties. From the authorizing order, it is apparent that one of the functions of the C of G was to ensure that, in the event of war on Canadian soil, the defenders would possess detailed and accurate information of the area of operations. The ranks of the Corps of Guides were filled quickly, and by the end of 1903, the General Officer Commanding the Militia was able to report that, “the formation of the Corps has been attended by the best possible results. Canada is now being covered by a network of Intelligence and capable men, who will be of great service to the country in collecting information of a military character and in fitting themselves to act as guides in their own districts to forces in the field. I have much satisfaction in stating that there is much competition among the best men in the country for admission into the Corps of Guides. Nobody is admitted into the Corps unless he is a man whose services are likely to be of real use to the country.” The training of the Corps began at once under the supervision of the . Special courses stressed the organization of foreign armies, military reconnaissance, and the staff duties of Intelligence officers. Instruction in drill and parade movements was kept to a minimum. Although primarily made up of individual officers and men, there was also an establishment for a mounted company of the Corps with one company allocated to each division. The strength of the company was 40 all ranks. Each Military District was sub-divided into local Guide Areas.

The head of this organization was “a Director General of Military Intelligence (DGMI),” under the control of the General Officer Commanding (GOC). “The DGMI was charged with the collection of information on the military resources of Canada, the British Empire, and foreign countries.”

Canadian Corps of Guides uniform, ca. 1901, Base Borden Military Museum, CFB Borden, Ontario. Another C of G uniform is preserved in the New Brunswick Museum, Saint John, New Brunswick.

(Photo Courtesy Bryan Gagne)

Lieutenant Cyril Tweedale, Corps of Guides.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, PA-111891)

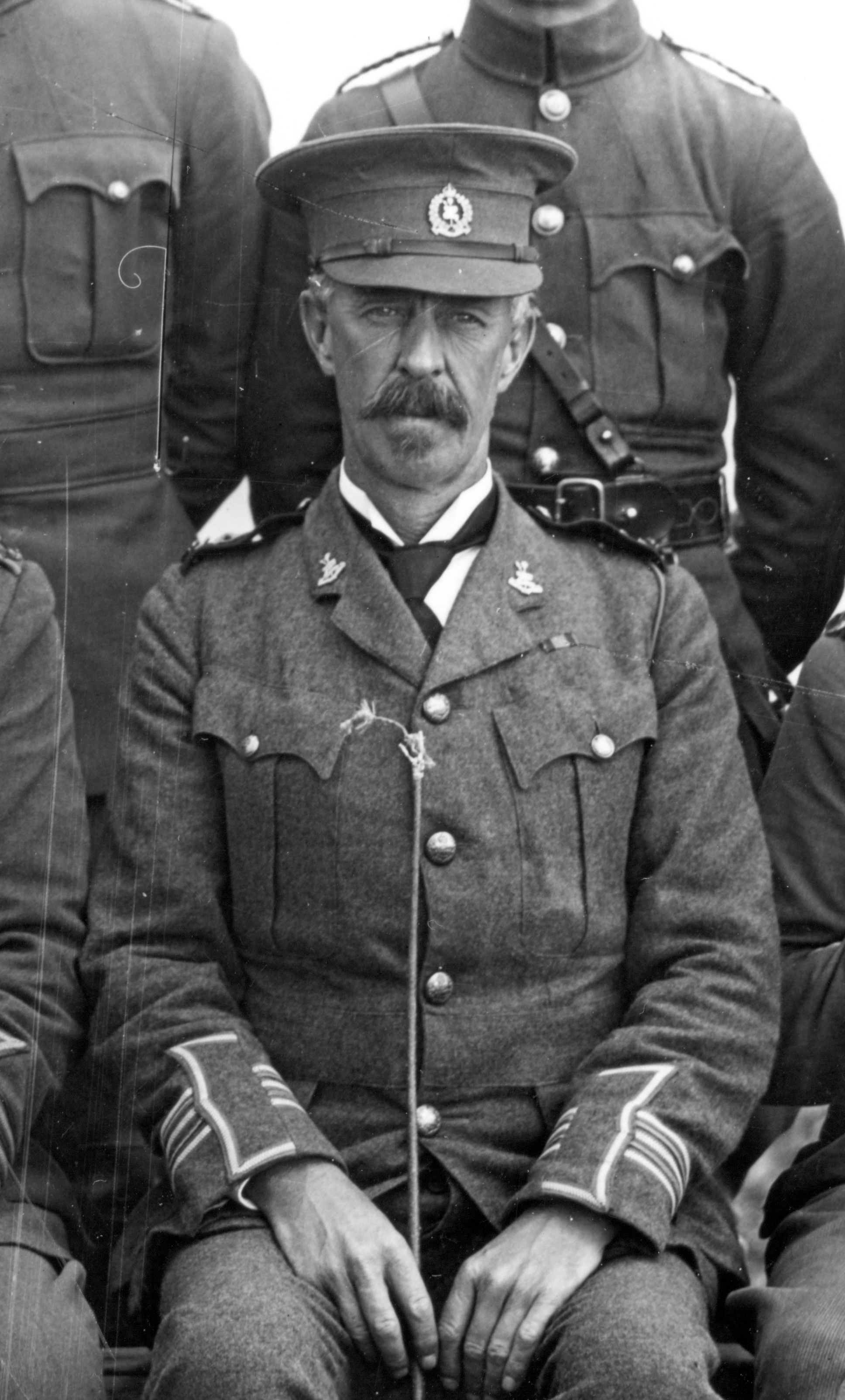

Canadian Corps of Guides at Niagara on the Lake, Ontario, ca 1903.

(Photo courtesy of Clive Law)

Canadian Corps of Guides group photo post 1903.

(Photo courtesy of Clive Law)

Canadian Corps of Guides Officer, post 1903.

“The first DGMI was Brevet-Major William A.C. Denny, Royal Army Service Corps, psc, a veteran of South Africa.” His staff included LCol Victor Brereton Rivers as ISO and two AISOs, Capt A.C. Caldwell and Capt W.B. Anderson responsible respectively for the Information and Mapping Branches, three Lieutenants, a Sergeant and two NCOs. All officers and men in the Districts were Militia. (As late as 1913 there were less than 3,000 men serving in the Canadian Militia). This was the basic organization for military Intelligence with which Canada entered the Great War.

(Steve Tijou Photo)

Capt George Bryant Schwartz (1890-1958), wearing a Corps of Guides cap badge. Captain Bryant served with the 3rd Divisional Cyclist Company, Toronto. He left for England in January 1916 and was part of the Canadian Corps Cyclist Battalion

1914-1918, Canadian Military Intelligence in the Great War

Canada’s military intelligence came of age in the Great War. Because it was part of the British Empire,when Britain declared war on 4 August 1914, Canada also found itself atwar. “The machinery of strategic Intelligence” was at that time “located in, responsible to, and managed by ”Britain’s “Whitehall.” “The Canadian Director General of Military Intelligence (DGMI) had been required since 1903 to gather information on foreign armies, Militia, military engineering and to prepare reports for any Army in the field.” Militia Headquarters in Ottawa,however, “had no direct access to official foreign sources” and agencies and“there were no Canadian offices abroad.”[1]

Before the war, Ottawa had periodically forwarded Intelligence gathered on Canada’s military resources to the Colonial Office for use by the Committee on Imperial Defence. The forwarding of Intelligence to Great Britain highlights the fact that it would have been very unlikely that Canada would have stood aside even if it had a choice, when the British Empire went to war. In fact, Canada specifically endeavoured to “acquaint the Imperial authorities with the material [Canadian]resources upon which the Empire might reckon in the event of a Great War.”[2]

When the Great War broke out, “the Corps of Guides volunteered for service in a body and a concentration…moved to Valcartier as part of the general mobilization” then in progress. It quickly became evident however, “that the Corps could not be employed under the conditions of warfare” for which it had been designed. General Sir Arthur Currie[3] recorded:

“The Corps of Guides was absorbed into existing Units and formations. Officers to the number of about thirty were absorbed into Staff posts and various regimental and special duties. Owing to their special training in reconnaissance and scout duties generally, the officers appointed to Staff duties were utilized essentially as Staff Captains for Intelligence and General Staff Officers. Non-Commissioned Officers and men were absorbed into cavalry, horse artillery and various other Staff duties and, subsequently, into the Cyclist Corps which later became the natural channel for the absorption of the Guide personnel.”[4]

“Canadian Army personnel were also attached to the British Intelligence Corps for employment in Intelligence duties such as liaison and Counter Intelligence.”[5] In spite of their limited training, the Guides were still better prepared than their English counterparts were for the mud of Flanders. “Their very existence kept the importance of battlefield Intelligence highly visible,” which may explain why “Canadian formations tended to employ more Staff Officers on Intelligence duties than their British equivalents did.”[6]

[1] Ibid.,p. 23.

[2] MilitiaReport, 31 March 1908. Dan R. Jenkins, The Corps of Guides, p. 97.

[3] Sir ArthurCurrie was the first Canadian-appointed commander of the Canadian Corps in WW I. Arthur Currie participated in all majoractions of the Canadian forces in First World War, including the planning andexecution of the assault on Vimy Ridge. Arthur Currie is best known for his leadership during the last 100 Daysof WW I and as a successful advocate of keeping Canadians together as a unifiedfighting force. He was born on 5 Dec 1875 in Napperton, Ontarioand died 30 Nov 1933in Montreal, Quebec.

[4] Major J.E.Hahn, The Intelligence Service Withinthe Canadian Corps, 1914-1918, (Toronto: The Macmillan Company of CanadaLtd, at St. Martin’s House, 1930), p. xiii-xiv.

[5] Edmond Cloutier, The Canadian Intelligence Corps,p. 5.

[6] Dan R.Jenkins, The Corps of Guides,p. 97.

By 1914, the Canadian Corps of Guides totaled some 500 all ranks. When the Great War broke out, “the Corps of Guides volunteered for service in a body and a concentration…moved to Valcartier as part of the general mobilization” then in progress. It quickly became evident however, “that the Corps could not be employed under the conditions of warfare” for which it had been designed. Given that their mounted scout role appeared inappropriate for war in Europe, many of the personnel serving with the Corps of Guides were absorbed into existing units and formations in the Canadian Army. Others became Intelligence staff officers and NCOs serving with the British Intelligence Corps. Some continued to serve in Canada with the Canadian Corps of Guides. When the Militia units were mobilized in British Columbia they were concentrated within the 5th Western Cavalry.

(Author Photo, Fredericton Region Museum Collection)

5th Western Cavalry

5th Western Cavalry cap badge with C of G on the lower right wreath, ca. 1914. When the Great War began, military units in British Columbia were mobilized and collected into the 5th Western Cavalry. The C of G personnel included in this unit were the only ones officially mobilized. In keeping with their role as mounted reconnaissance and intelligence collection personnel, many of the remaining C of G personnel went into the Canadian Cyclist Corps.5th Battalion (Western Cavalry). Authorized 10 August 1914, disbanded 15 September 1920.

The 5th Battalion sailed for England without regimental badges. After the arrival of the 1st Contingent in England in October 1914 General Alderson gave verbal authority that the battalions of the 1st Division could adopt battalion cap badges at unit expense. Designs for cap badges of all four battalions of the 2nd Infantry Brigade, the 5th, 6th 7th and 8th, were submitted by the Brigadier General A.W. Currie to the Assistant Adjutant General on October 25th 1914 shortly after the arrival of the 1st Contingent in the United Kingdom. (The 6th Battalion was replaced in the 2nd Infantry Brigade by the 10th Battalion before they sailed for France in February 1915.) No sample badges are currently known for the 5th Battalion, presumably the patterns submitted being accepted. The 5th Battalion cap badges were worn with a red felt insert behind the voided centre. The central design of the badge is surrounded with a laurel wreath entwined with a ribbon bearing the titles of the units forming the 5th Battalion. These being the 12th Manitoba Dragoons, 15th Light Horse, 27th Light horse, 29th Light horse, 30th BC Horse, 31st BC Horse, and the 35th Central Alberta Horse, the badge also bears a ‘Corps of Guides’ of which 235 troopers had arrived at Camp Valcartier to join the 1st Contingent these being distributed amongst other units as there was no matching unit within the British Army establishment, with the exception of the Indian Army. A close examination of the regimental designations will show that a number of these are wrongly numbered.

Minister Sam Hughes set up the battalion system and only allowed numbered Battalions. People want names and characters to support & cheer for, so nicknames crept in as the war progressed. Eventually, add-on names were recognized. The government allowed special interests like the Tigers(football), Bantams and Irish to organize themselves. The 5th Battalion (Western Cavalry), CEF, was known as “Tuxford’s Dandy’s, and was recruited in Brandon, Manitoba; Saskatoon, Regina and Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan; Red Deer, Alberta and Merritt and Vernon, British Columbia -so it was really “Western” . (Canadian Virtual Military Museum)

The Intelligence system created within the First Canadian Division prior to its deployment to France in 1915 served as the basis for the development of Intelligence structures generally throughout the Canadian Corps. Intelligence personnel exploited reports from ground and aerial observers, patrols, aerial photography, Prisoners of War (PWs), and captured enemy documents. They conducted intelligence preparation of the battlefield activities and issued regular INTSUMs.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3403628)

Soldiers taking a compass traverse on an Intelligence course at Camp Borden, Ontario, 26 Sep 1916.