Japanese Weapons and Artifacts of the Second World War preserved in Canada

For the definitive Canadian reference site on Japanese small arms see “Nambu World: Teri Jane Bryant’s Second World War Japanese Handgun Website” at www.nambuworld.com.

Photos are by the Author except where otherwise credited.

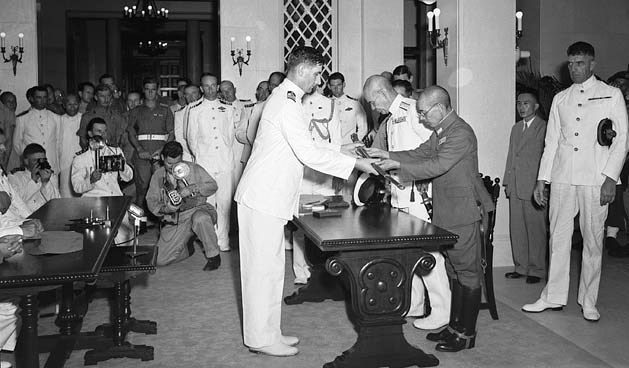

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3193143)

Major-General Okada handing over his sword during a ceremony marking the surrender of Japanese forces in Hong Kong, Government House, 16 Sep 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3590968)

Swords surrendered by Japanese Officers in Japan, including two from General Yamashita, August 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3365325)

Group of Canadian officers with Japanese flag and swordacquired during service in India and Burma, New York, NY, 20 Feb 1946.

(Author Photos)

7.7-mm Nambu Type 99 Light Machine Gun. New Brunswick Museum, Saint John, New Brunswick.

7.7-mm Nambu Type 99 Light Machine Gun held by a Canadian member of the joint American-Canadian landing force. He found this Japanese machine gun in a trench on Kiska Island, Alaska, on 16 August 1943. After the brutal fighting in the battle to retake Attu Island, U.S. and Canadian forces were prepared for even more of a fight on Kiska. Unknown to the Allies though, the Japanese had evacuated all their troops two weeks earlier. Although the invasion was unopposed, 32 soldiers were killed in friendly-fire incidents, four more by booby traps, and a further 191 were listed as Missing in Action. (US Library of Congress Photo)

(Author Photos)

8-mm Nambu Taisho 14th Year Type 14 semi-automatic pistol wth small trigger guard. New Brunswick Military History Museum (Fredericton).

(Author Photo)

Similar to this 8-mm Nambu Taisho 14th Year Type 14 semi-automatic pistol wth small trigger guard. Cole Land Transportation Museum, Bangor, Maine.

(Author Photos)

8-mm Nambu Taisho 14th Year Type 14 semi-automatic pistol wth large trigger guard. New Brunswick Military History Museum (Fredericton).

(Author Photo)

8-mm Nambu Type 94 semi-automatic pistol. New Brunswick Military History Museum (Fredericton).

(Author Photo)

Similar to this 8-mm Nambu Type 94 semi-automatic pistol wth small trigger guard. Cole Land Transportation Museum, Bangor, Maine.

(Author Photos)

7.7-mm Ariska Type 99 bolt action rifle. Bathurst Legion Museum, Bathurst, New Brunswick.

(Author Photos)

7.7-mm Ariska Type 99 bolt action rifle, with Imperial Chrysanthemum undamaged, and one partially defaced (often ground off the receiver to prevent embarrassment to the Emperor should the rifle pass into foreign hands). NBMHM Collection.

(Author Photos)

Japanese Army Kyu Gunto Sword. New Brunswick Military History Museum.

(Author Photo)

Japanese Army Kyu Gunto Sword. RCAF Officer’s Mess, Ottawa, Ontario.

(Author Photo)

Japanese helmet. New Brunswick Military History Museum, 5 Canadian Division Support Group Base Gagetown, New Brunswick.

(Author Photo)

Japanese military display in the New Brunswick Military History Museum, 5 Canadian Division Support Group Base Gagetown, New Brunswick

(Author Photo)

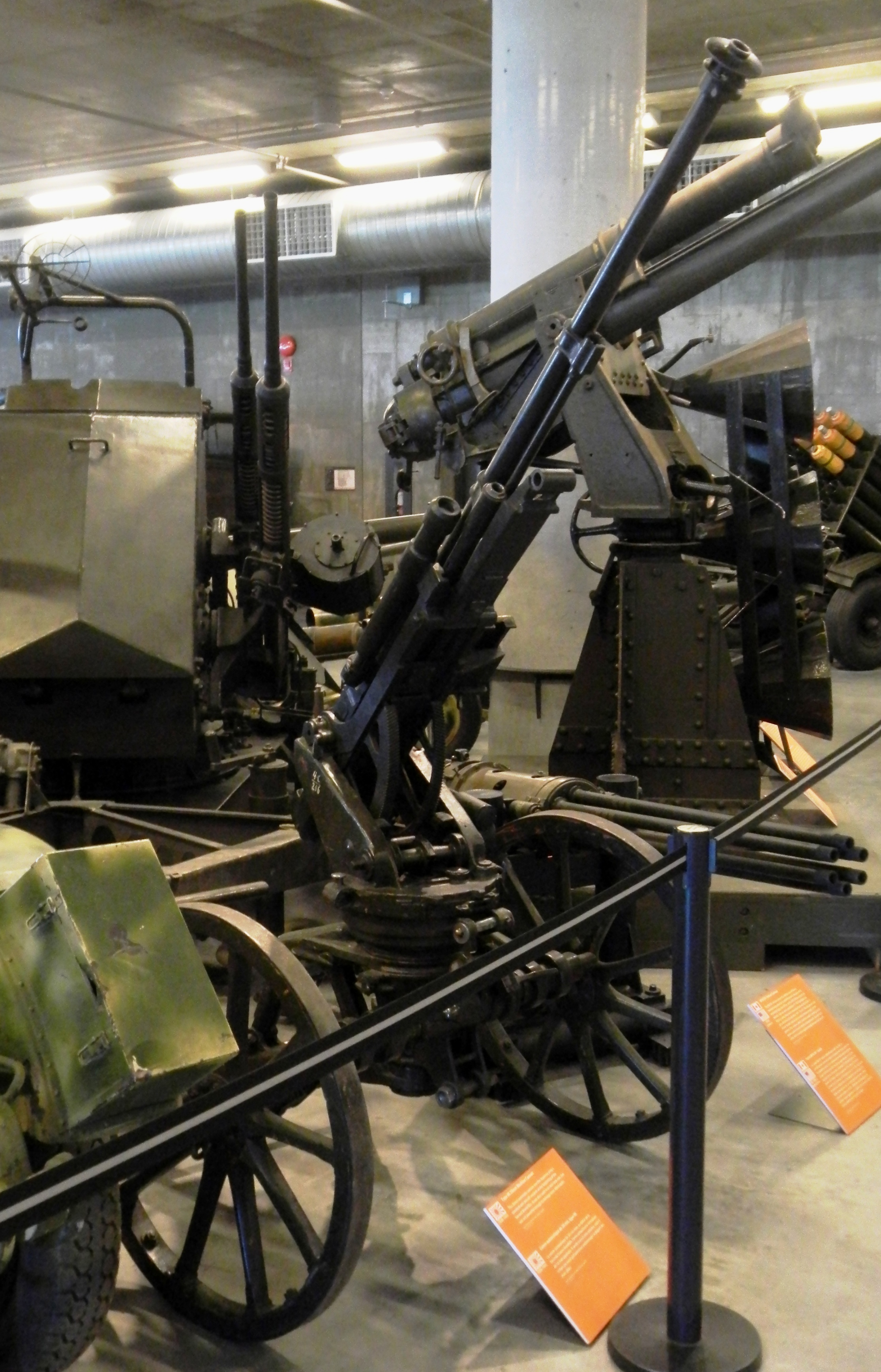

20-mm Type 98 AA Machine Cannon, Canadian War Museum, Ottawa, Ontario.

(IJA Photo)

70-mm Type 92 Battalion Gun.

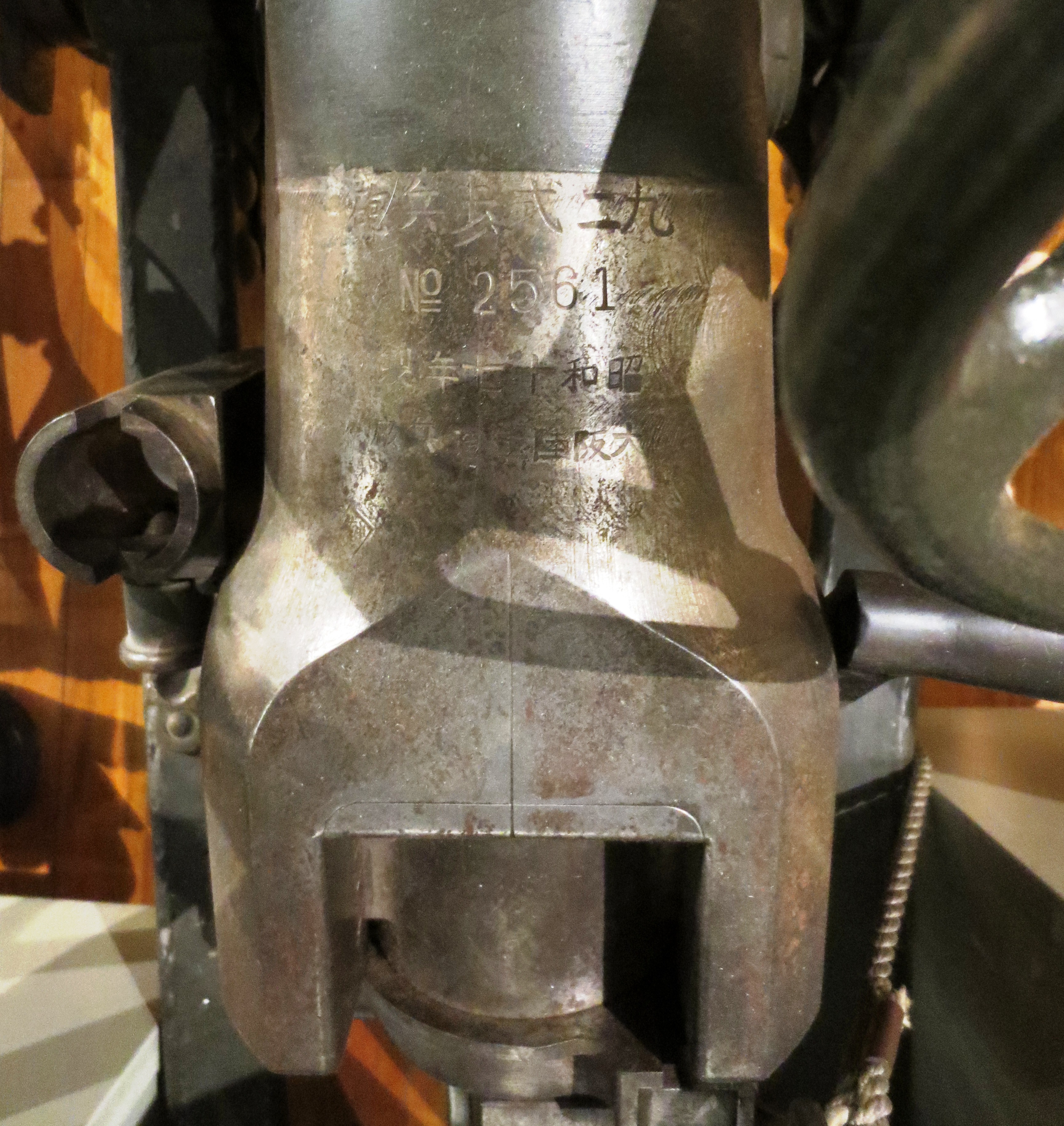

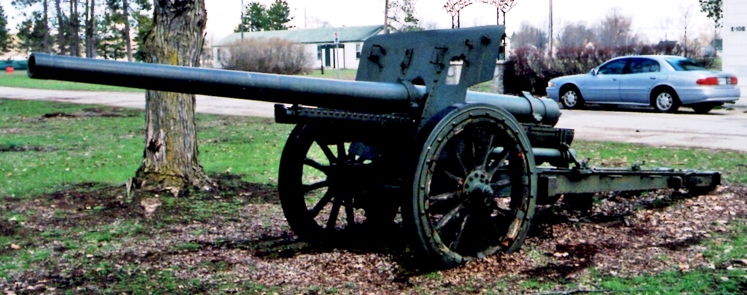

(Author Photos)

70-mm Type 92 Battalion Gun. New Brunswick Military History Museum, 5 Canadian Division Support Group Base Gagetown, New Brunswick.

(Author Photo)

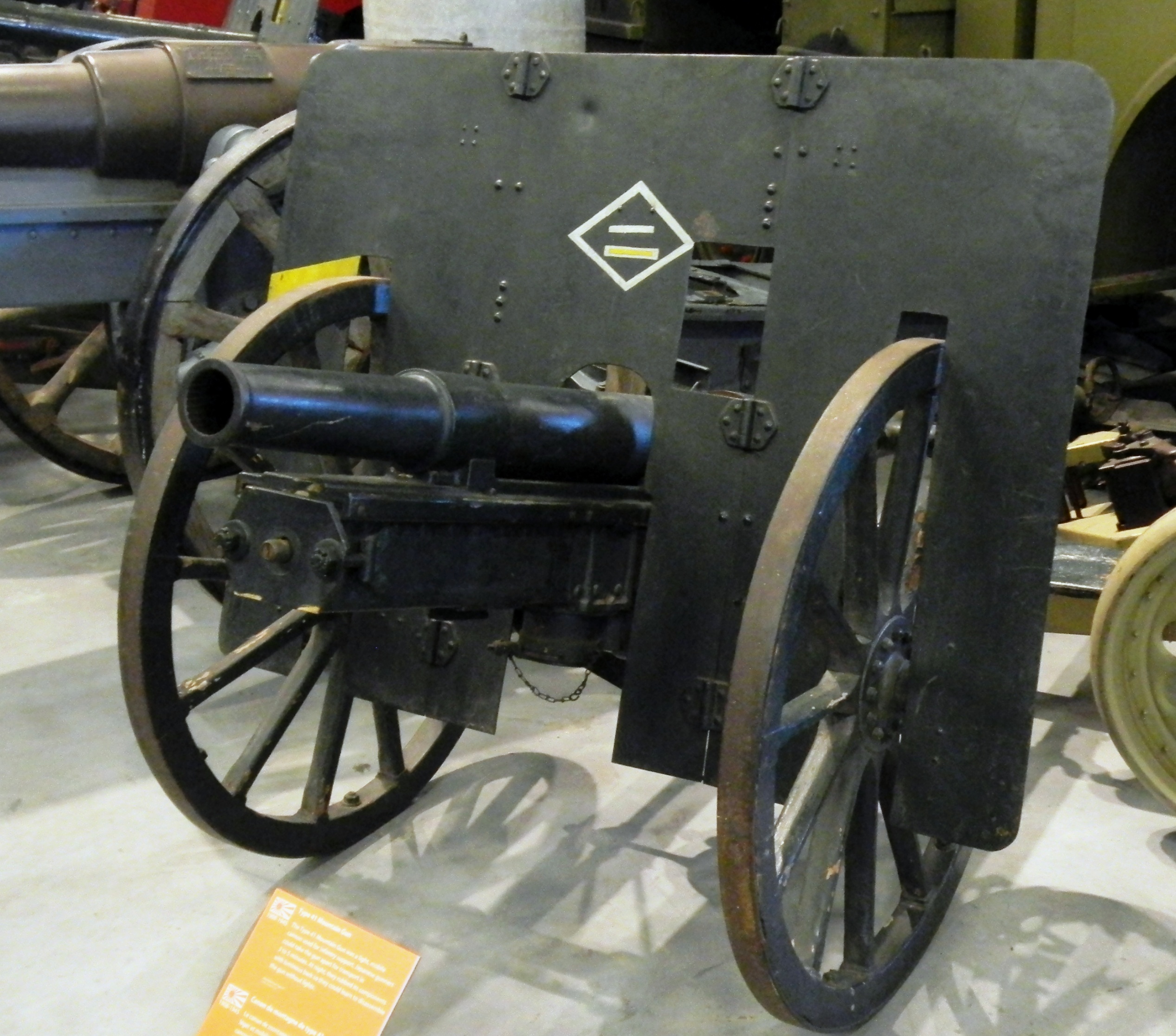

75-mm Type 41 Mountain Gun. Canadian War Museum, Ottawa, Ontario.

(Balcer Photo)

75-mm Type 41 Mountain Gun. RCR Museum, London, Ontario.

(Base Borden Military Museum Photos, left, Guy Despatie Photo, right)

(Andre Blanchard Photo)

(Guy Despatie Photos)

100-mm Type 92 Field Gun, Base Borden Military Museum, CFB Borden, Ontario.

(Bob Spring Photo)

(John Eckersley Photo)

76-mm QF Naval Gun, probable Type 41 3-inch (76.2 mm)/40) Naval Gun, captured at Kiska, Alaska where it was employed in coastal defence by the Japanese occupation forces. Vernon Army Cadet Summer Camp, British Columbia. This Japanese Gun’s breech is stamped 76m Q.F. N211945, 1898. The Japanese characters stamped above the breech translate to “No. 328”.

Type 41 3-inch (76.2 mm)/40 QF Naval Gun

The 12 pounder 12 cwt QF Naval Gun was a common 3-inch (76.2-mm) calibre naval gun introduced in 1894 and used until the middle of the 20th century. It was produced by Armstrong Whitworth, Elswick and used on Royal Navy warships, and exported to allied countries. In British service, “12-pounder” was a rounded reference to the projectile weight and “12 cwt” referred to the weight of the barrel and breech: 12 hundredweight = 12 x 112 pounds = 1,344 pounds, to differentiate it from other “12 pounder” guns. As the Type 41 3-inch (76.2 mm)/40 naval Gun it was used on most early battleships and cruisers of the Imperial Japanese Navy, though it was commonly referred to by its UK designation as a “12-pounder” gun.

The 76-mm QF Naval Gun (Type 41) on display at the Vernon Army Cadet Camp in British Columbia was originally captured by the Japanese at Singapore in 1941. The Japanese No. 3 Special Landing Party and 500 Marines went ashore at Kiska, Alaska on 6 June 1942 capturing the ten-man US Navy Weather Detachment based there. The gun was then set up in a coastal defence position on the beach at Kiska. The Japanese became aware of a large Allied invasion force headed their way after the loss of the island of Attu. They successfully withdrew their troops under the cover od severe fog on 28 July without being detected. On 15 August 1943, an Allied invasion of 34,426 troops including 5,300 Canadians landed on the island and discovered it had been completely abandoned. In spite of this, there were casualties, with 17 Americans and four Canadians dying as a result of preparatory suppresion fire and, booby traps.

The Naval gun was collected and brought to Vernon in 1944 by Canadian Engineers. It was set up in front of their mess hall where it stood for a few years until being moved to its present display location in front of the headquarters of the Vernon Army Cadet Summer Camp. The gun serves as a memorial to the four Canadian fatalities from the Winnipeg Grenadiers, the Fusiliers de Mont-Royal and the Rocky Mountain Rangers.

Japanese uniform and weapons display. Canadian War Museum, Ottawa, Ontario.

7.7-mm Nambu Type 99 Light Machine Gun. Canadian War Museum, Ottawa, Ontario.

8-mm Nambu Taisho 14th Year Type 14 semi-automatic pistol wth large trigger guard. Canadian War Museum, Ottawa, Ontario.

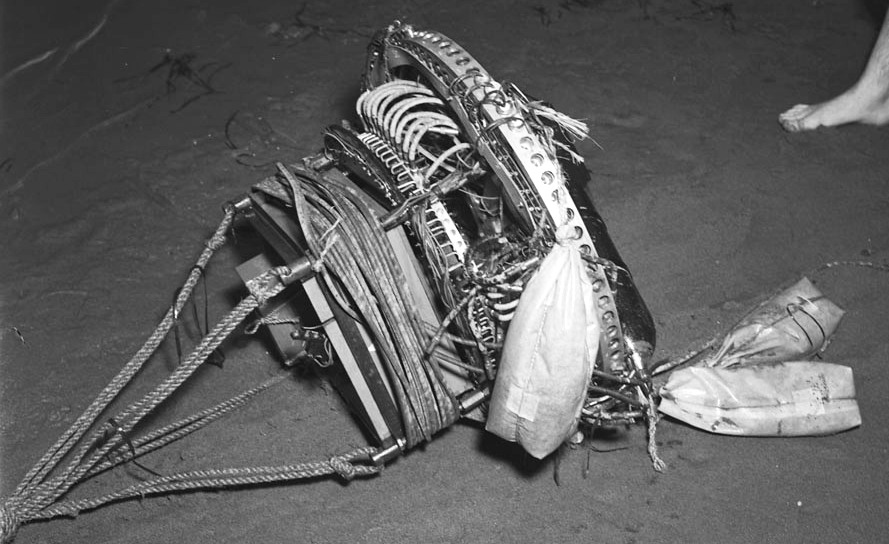

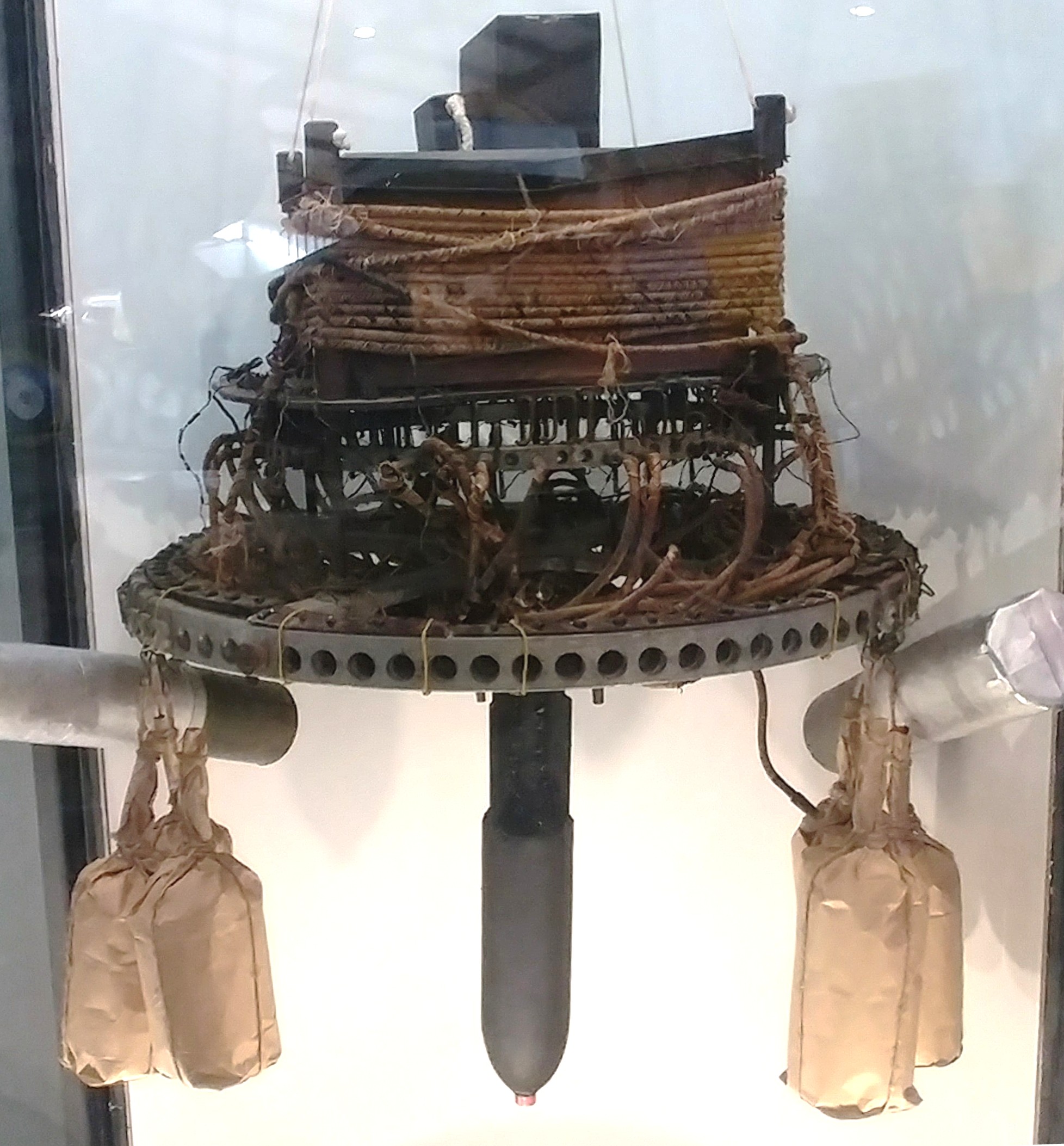

Japanese Balloon Bomb (f?sen bakudan). This balloon had been shot-down and re-inflated by the USAAF in California. In February and March 1945, Curtiss P-40 Kittyhawk fighter pilots from 133 Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force operating out of RCAF Patricia Bay, near Victoria, British Columbia, intercepted and destroyed two of these balloon bombs. On 10 March 1945, Pilot Officer J. O. Patten destroyed another balloon bomb near Saltspring Island, British Columbia. The remains of Balloon bombs have been found in Montana and Arizona, and inside Canada in Saskatchewan, in the Northwest Territories, and in the Yukon Territory.

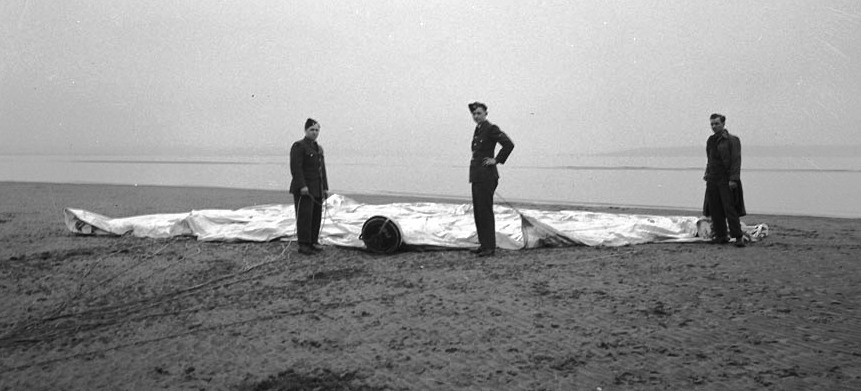

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 5012878)

Japanese balloon bomb that landed off Point Roberts, BC, 18 Apr 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3574157)

Japanese balloon bomb that landed off Point Roberts, BC, 18 Apr 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3574157)

Japanese balloon bomb that landed off Point Roberts, BC, 18 Apr 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 5012879)

Japanese balloon bomb that landed off Point Roberts, BC, 18 Apr 1945.

(Author Photo, 28 Jan 2019)

Japanese Balloon Bomb, on display in the British Columbia Aviation Museum (BCAM), Sidney, British Columbia.

(Author Photo)

Japanese Balloon Bomb (f?sen bakudan) ordnance display in the Canadian War Museum, Ottawa, Ontario.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3599747)

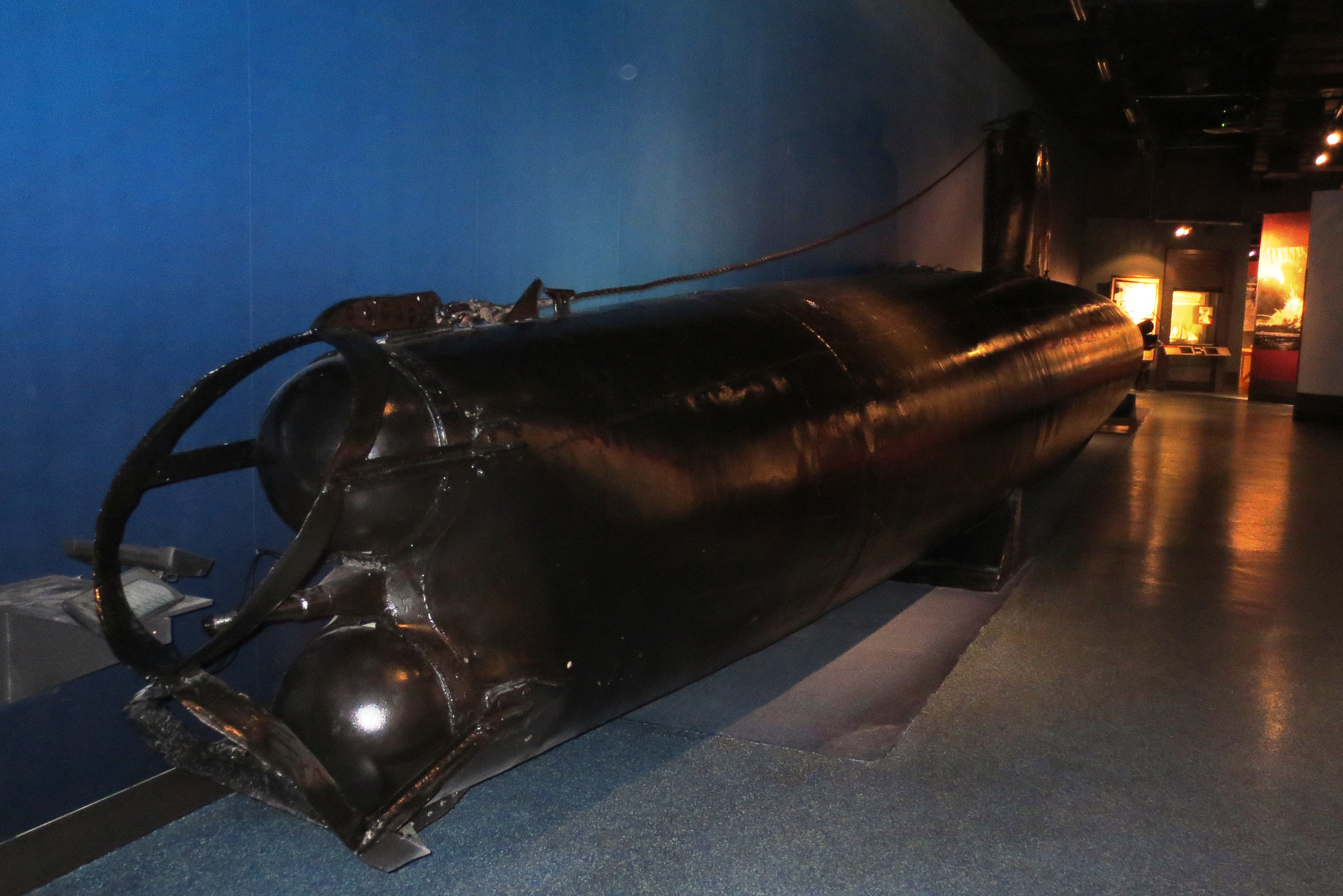

Canadian and American soldiers examine abandoned Imperial Japanese Navy Ko-hyoteki class midget submarines found at Kiska in the Aleutian Islands, Alaska, 1 Sep 1943.

(USN Photo)

A heavily damaged midget submarine base constructed by occupying Japanese forces on Kiska Island, photo taken sometime in 1943, after Allied forces retook the island.

(Author Photo)

Imperial Japanese Navy Ko-hyoteki class midget submarine used at Pearl Harbor on 7 Dec 1941. National Museum of the Pacific War, Fredericksburg, Texas.

(Library & Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4105388).

Curtiss P-40E Kittyhawks, No. 111 (F) Sqn, RCAF, Kodiak, Alaska, 1942-43. A P-40K was flown by Squadron Leader K.A. Boomer when he shot down a Japanese Rufe floatplane on 25 Sep 1942.

(IJNAF Photo)

Japanese Naval Air Force Nakajima A6M2-N Type 2 Rufe floatplane in flight.

(Author Photo)

Japanese Naval Air Force Kawanishi N1K-1 Kyofu (Mighty Wind) George floatplane (Serial No. 562). National Museum of the Pacific War, Fredericksburg, Texas.

Japanese Decorations and Medals

Very few Japanese medals, badges and decorations came into the hands of Canadian servicemen and women during the war, and even now there are only a few in private collections. Japanese medals fall into four main categories including Military Orders, Campaign/War Medals, Commemorative Medals and Medals for Meritorious Service. All of these decorations were administered by the Japan Medals and Awards Department. Unlike Commonwealth war medals, the Japanese medals were not “named”, but rather were accompanied by large-format certificates with the recipient’s name. Badges generally were allotted into two categories, which included proficiency badges and association badges.

Medals worn by Imperial Japanese Army and Navy personnel included awards dating back to the late 19th century. In 1875, the Meiji 8 Medal was established. This decoration is the forerunner of the Order of the Rising Sun. It was followed in 1876 by the Meiji 9 Medal. This was a Medal of Merit and was initially worn with crimson, green, and blue ribbons. A yellow ribbon was added in 1887, a dark blue ribbon was added in 1919, and most recently, a purple ribbon was added in 1955.

(Teri Jane Bryant Photo)

7th Class Order of the Golden Kite, Teri Jane Bryant Collection.

(Teri Jane Bryant Photo)

8th Class Order of the Sacred Treasure, Teri Jane Bryant Collection.

(Teri Jane Bryant Photo)

8th Class Order of the Rising Sun, Teri Jane Bryant Collection.

In 1888 (Meiji 21) Order of the Sacred Treasure and the Order of the Sacred Crown were instituted (the later was awarded to women only). The 8th Class shown above was awarded to ordinary soldiers, and low-ranking officers. All classes of the Order of the Golden Kite were available only to the military. All classes of the Order of the Rising Sun were available to both military and civilian personnel (and some have been awarded to foreigners). The 8th Class Order of the Rising Sun (Order of the White Pawlonia Leaves) was awarded to both civilian and military personnel.

The Order of the Golden Kite was established in 1899 (Meiji 23). The final wartime order was the 1937 Showa 12 Order of Culture. No official campaign or commemorative medals were made after 1945. The last medal approved was the Great East Asia War Medal in 1944, which would have been awarded for victory in the Pacific, but only a few were awarded posthumously, with the remainder apparently destroyed. The Order of the Rising Sun and the Order of the Sacred Treasure were awarded long after the war ended, but the lower classes were finally abolished within the last few years. The Order of the Golden Kite was abolished after the war.[1]

(Terry Jane Bryant Photo)

The Manchurian Incident Medal, established in 1934, was awarded for service in the 1931-1934 Manchurian Campaign (Showa 6 to 9),was awarded for general military service. One of the few service medals awarded to most of the Japanese soldiers who fought in the Second World War. (TJB)

(Terry Jane Bryant Photo)

The China Incident Medal, established in 1939, was awarded for general military service. These were generally the only service medals awarded to most of the Japanese soldiers who fought in the Second World War. (TJB)

Japanese Military casualties in the Second World War amounted to 2,566,000 Imperial Armed Forces dead, including non-combat deaths, with 1,506,000 killed in action. 810,000 were listed as missing in action and presumed dead. There are 672,000 known civilian dead.[2]

[1] Teri Jane Bryant; and James W. Peterson, Orders and Medals of Japan and Associated States, (Orders and Medals Society of America, 2000)

[2] Internet: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imperial_Japanese_Army.

The fall of Hong Kong

The winter of December 1941 was a hard one for Canada and its allies. The Japanese attack on the Hawaiian Island of Oahu on 7 Dec took most of the headlines, but Canadians were already involved in the Pacific theatre, having sent soldiers to Hong Kong just before the conflict began. Britain had first thought of Japan as a threat with the ending of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in the early 1920s, a threat which increased with the expansion of the Sino-Japanese War. On 21 October 1938 the Japanese occupied Canton (Guangzhou) and Hong Kong was effectively surrounded. Various British Defence studies had already concluded that Hong Kong would be extremely hard to defend in the event of a Japanese attack, but in the mid-1930s, work had begun on new defences. Although Winston Churchill and his army chiefs initially decided against sending more troops to the colony, they reversed their decision in September 1941 in the belief that additional reinforcements would provide a military deterrent against the Japanese.

In the fall of 1941, the British government accepted an offer by the Canadian Government to send two infantry battalions and a brigade headquarters (1,975 personnel) to reinforce the Hong Kong garrison. The Canadian battalions were the Royal Rifles of Canada from Quebec and the Winnipeg Grenadiers from Manitoba.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396534)

Royal Rifles of Canada, disembarking from HMCS Prince George, Hong Kong, 16 Nov 1941.

The Royal Rifles were serving in New Brunswick where they recruited a large number of soldiers from across the province as well as from PEI and Nova Scotia. In the fall of 1941 these soldiers were deployed to Gander, Newfoundland, where they served on Coastal Defence duties. From there they redeployed to Valcartier where they were outfitted for tropical operations. They travelled by train to the port of Vancouver where they joined up with the Winnipeg Grenadiers. These two units were formed into a formation designated as “C Force” and on 27 October they embarked on board the troopship Awatea and the armed merchant cruiser Prince Robert. They arrived in Hong Kong on 16 November 1941, but without all of their equipment as a ship carrying their vehicles was diverted to Manila at the outbreak of war.

The Royal Rifles had served only in Newfoundland and New Brunswick prior to their duty in Hong Kong, and the Winnipeg Grenadiers had been serving in Jamaica. As a result, many of these Canadian soldiers did not have much field experience before arriving in Hong Kong. Unfortunately, these were the soldiers who found themselves engaged in the Battle of Hong Kong which began on 8 December 1941 and ended on 25 December 1941 with the surrender of the Crown colony to the Empire of Japan. More than 100 casualties suffered by the Royal Rifles during this battle were soldiers recruited from New Brunswick.

The Japanese attack began shortly after 08:00 on 8 December 1941 less than eight hours after the Attack on Pearl Harbor. British, Canadian and Indian forces, commanded by Major-General Christopher Maltby supported by the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps resisted the Japanese invasion by the Japanese 21st, 23rd and the 38th Regiments, commanded by Lieutenant General Takashi Sakai. Some 52,000 Japanese assaulted the 14.000 Hong Kong defenders, most of whom lacked the recent combat experience of their opponents.

The colony had no significant air defence. The Commonwealth forces decided against holding the Sham Chun River which separated Hong Kong from the mainland and instead established three battalions in a defence position known as the Gin Drinkers’ Line across the hills. The Japanese 38th Infantry under the command of Major General Takaishi Sakai quickly forded the Sham Chun River by using temporary bridges. Early on 10 December 1941 the 228th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel Teihichi, of the 38th Division attacked the Commonwealth defences at the Shing Mun Redoubt defended by the 2nd Battalion Royal Scots. The line was breached in five hours and later that day the Royal Scots also withdrew from Golden Hill. D company of the Royal Scots counter-attacked and captured Golden Hill. By 10:00am the hill was again taken by the Japanese. This made the situation on the New Territories and Kowloon untenable and the evacuation from them began on 11 December 1941 under aerial bombardment and artillery barrage. Where possible, military and harbour facilities were demolished before the withdrawal. By 13 December, the 5/7 Rajputs of the British Indian Army, the last Commonwealth troops on the mainland had retreated to Hong Kong Island.

MGen Maltby organised the defence of the island, splitting it between an East Brigade and a West Brigade. On 15 December, the Japanese began systematic bombardment of the island’s North Shore. Two demands for surrender were made on 13 December and 17 December. When these were rejected, Japanese forces crossed the harbour on the evening of 18 December and landed on the island’s North-East. That night, approximately 20 gunners were massacred at the Sai Wan Battery after they had surrendered. There was a further massacre of prisoners, this time of medical staff, in the Salesian Mission on Chai Wan Road. In both cases, a few men survived to tell the story.

On the morning of 19 December fierce fighting continued on Hong Kong Island as the Japanese annihilated the headquarters of West Brigade. A British counter-attack could not force them from the Wong Nai Chung Gap that secured the passage between the north coast at Causeway Bay and the secluded southern parts of the island. From 20 December, the island became split in two with the British Commonwealth forces still holding out around the Stanley peninsula and in the West of the island. At the same time, water supplies started to run short as the Japanese captured the island’s reservoirs.

On the morning of 25 December, Japanese soldiers entered the British field hospital at St. Stephen’s College, and tortured and killed a large number of injured soldiers, along with the medical staff. By the afternoon of 25 December 1941, it was clear that further resistance would be futile and British colonial officials headed by the Governor of Hong Kong, Sir Mark Aitchison Young, surrendered. The garrison had held out for 17 days.

The Allied dead from the campaign, including British, Canadian and Indian soldiers, were eventually interred at the Sai Wan Military Cemetery and Stanley Military Cemetery. A total of 1,528 soldiers, mainly Commonwealth, are buried there. At the end of February 1942, The Japanese government stated that numbers of prisoners of war in Hong Kong were: British 5,072, Canadian 1,689, Indian 3,829, others 357, for a total of 10,947. Of the Canadians captured during the battle, 267 subsequently perished in Japanese prisoner of war camps.

Following the battle, John Robert Osborn was awarded the Victoria Cross. After seeing a Japanese grenade roll in through the doorway of the building Osborn and his fellow Canadian Winnipeg Grenadiers had been garrisoning, he took off his helmet and threw himself on the grenade, saving the lives of over 10 other Canadian soldiers.[1]

Canada responded to the outbreak of war with Japan by significantly strengthening its Pacific coastal defences, ultimately stationing more than 30,000 troops, 14 RCAF squadrons, and over 20 warships in British Columbia. Canadian forces also co-operated with the United States in clearing the Japanese from the Aleutian Islands off Alaska. Before Japan surrendered in August 1945, a Canadian cruiser, HMCS Uganda, particpated in Pacific naval operations, two RCAF transport squadrons flew supplies in India and Burma, and communications specialists served in Australia.

(Author Photos)

Hong Kong War Memorial, Ottawa.

Axis Warplane Survivors

A guidebook to the preserved Military Aircraft of the Second World War Tripartite Pact of Germany, Italy, and Japan, joined by Hungary, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia; the co-belligerent states of Thailand, Finland, San Marino and Iraq; and the occupied states of Albania, Belarus, Croatia, Vichy France, Greece, Ljubljana, Macedonia, Monaco, Montenegro, Norway, Cambodia, China, India, Laos, Manchukuo, Mengjiang, the Philippines and Vietnam.

The book may be ordered online at:

http://www.lulu.com/shop/harold-a-skaarup/axis-warplane-survivors/paperback/product-20360959.html

http://www.chapters.indigo.ca/books/search/?keywords=axis%20warplane%20survivors&pageSize=12.

[1] Internet: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Hong_Kong.