Roll Call, Newsletter of the Friends of the New Brunswick Military History Museum (FNBMHM)

ROLL CALL

NEWSLETTEROF THE FRIENDS OF THE NEW BRUNSWICK MILITARY HISTORY MUSEUM

AMIS/AMIES DE MUSEÉ D’HISTOIRE MILITAIRE DU NOUVEAU-BRUNSWICK

Volume 8, Issue 1 Spring 2022

Roll Call is published four times a year: Spring, Summer, Fall, and Winter.

Submissions or comments can be sent to the Editor, Brent Wilson, at: jwilson@unb.ca.

For details on joining the Friends, please contact the Museum at 506-422-1304or email us at: friendsnbmhm@gmail.com.

Friends of the New Brunswick Military History Museum

Executive:

President-Brian MacDonald

Vice-President- Harold Skaarup

Secretary- Doug Hall

Treasurer-Randall Haslett

Directors-

Paul Belliveau

Gary Campbell

Robert Dallison

Brent Wilson

Harold Wright

The Revitalization of the NBMHM

by Captain David C. Hughes

I feel extremely lucky to be writing this article for the newsletter as the current Director/Museum Officer of the New Brunswick Military History Museum (NBMHM). For me this is a dream job, and I am excited to be leading the charge on the revitalization of the museum.

In April 2021, the commander of 5 CDSG, Colonel Dwayne Parsons, asked me to take over the museum as he knew that the previous Executive Director would be resigning. I said yes, of course, and immediately started work on bringing the NBMHM back to its former glory after many years of neglect. I am fortunate to have the support and advice of the executive of the Friends of the NBMHM. As we work together to make the NBMHM the true Centre of Excellence for all things related to New Brunswick military history, we are setting ambitious goals, creating new partnerships and opportunities, and bringing the rich military history of our province and its people to an even bigger audience every day.

Some aspects of the revitalization of the museum have already begun. In 2021, we developed the Class Visits Program, which will allow a teacher to either bring their students into the museum or for museum staff to “beam in” to the classroom via MS Teams. Participants from grade levels K to 12 will receive grade level appropriate learning from costumed interpreters that covers a variety of topics relating to the military history of the province over the centuries. The program was developed using the current New Brunswick Schools Curriculum Outcomes as a guide. So far, Anglophone School District West is on board. The COVID situation and current staffing shortages, however, forced us to put the program on hold until the new school year and we hope to begin delivering it to students starting in September 2022. Aswe move forward the goal is to make this program available to all school districts in the province, and to have it available in both English and French.

The weapons vault at the NBMHM was bursting at the seams with our vast collection of weapons. Rather than have them locked up and out of sight we are developing many new weapons displays at the museum where visitors can see an example of all the small arms used by the military in New Brunswick from the 1700’s to the present day. We also have a great collection of the weapons of our allies and adversaries.

We are developing Army, Navy, and Air Force “Profiles” galleries that will tell the stories of individual New Brunswickers who have served in those three arms of service. Also, we are creating The Royal New Brunswick Regiment Gallery. The story of the RNBR goes back over 250 years and touches almost every aspect of New Brunswick’s military history.

Colour of the 71st York Regiment which is perpetuated by the RNBR.

This gallery will be a miniature timeline but will be specific to the antecedent regiments of the RNBR. It will provide a proper home to the RNBR History Collection which was accessioned to the NBMHM by the Regiment a couple of years ago.

The “Feature Exhibit” plan has been put in place and has been very successful so far. Each Feature Exhibit highlights a particular aspect of the military history of the province. The exhibit is displayed in our front foyer for approximately a month at a time. We continue to receive donations and loans of artifacts from other museums, veterans’ groups, and private collectors. We are very grateful for all these items, and they are helping us to present fantastic stories of New Brunswick’s military history in an exciting and meaningful way.

Part of the overall plan for the museum was to also revitalize our social media presence. Our Facebook page has gone from about 500 page likes to over 2,400 page likes and over 2,500 followers. Posts are going up on the page almost daily and each month we are producing a video on the Feature Exhibit.

In the next few months, we will begin our “spring offensive” on our outdoor vehicle and field gun displays. Many of the monument vehicles and guns need restoration, a coat of paint, and some TLC. We will soon be putting the team together to make this happen so that visitors can stroll the museum grounds, and elsewhere on Base Gagetown, and see fine, properly maintained fighting vehicles, guns, and support vehicles from our history. I could go on and on about what we have going on at the NBMMHM but I will end here and advise the reader to check out our Facebook page at NBMHM-MHMNB, and visit the museum in person. We are currently open 9am to 4pm Monday to Friday and will be expanding our hours into the weekends and holidays starting in the summer.

Captain David C. Hughes, CD, is Executive Director of the New Brunswick Military History Museum. He is a 38-year veteran of the CAF. He and his wife, Geraldine Mazerolle, have two beautiful daughters, Sara, 16, and Emma, 13.

The NBMHM’s Russian T-72 Main Battle Tank

by Harold Skaarup

(Harold Skaarup Photo)

Many of us are watching the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. Both sides are using upgraded versions and variants of the Soviet-designed T-72 main battle tank that entered production in 1970. It was the most common tank deployed by the Soviet Army from the 1970s to the collapse of the Soviet Union. It has been widely exported and is used by more than 40 countries. In the 1970s, four that had been in service with the former East German Army came to CFB Gagetown (now 5 Canadian Division Support Base Gagetown).

The tanks were initially used as Opposition Force (OPFOR) trainers and provided realistic training for our combined arms forces participating in live training on base. Due to international agreements related to the Arms Verification Program, three were eventually turned into targets on the Gagetown ranges and one came to the NBMHM. The Armour School has assisted with keeping the T-72 in a presentable state.

Built in the former Soviet Union, the T-72 has been equipped with laser rangefinders since 1978. It is armed with a125-mm 2A46 series main gun and is capable of firing anti-tank guided missiles, as well as standard main gun ammunition, including High-explosive anti-tank(HEAT) and armour- piercing fin-stabilized discarding sabot (APFSDS) rounds. The125-mm main gun of the T-72 has a mean error of one metre (39 inches)at a range of 1,800 m (2,000yd). Its maximum firing distance is 9,100m (10,000 yd), due to limited positive elevation. The limit of aimed fire is 4,000 m (4,400 yd) (with the gun-launched anti-tank guided missile, which is rarely used outside the former USSR). The T-72’s main gun is fitted with an integral pressure reserve drum, which assists in rapid smoke evacuation from the bore after firing. The 125-mm gun barrel is certified strong enough to ram the tank through forty centimetres of iron-reinforced brick wall, though doing so will negatively affect the gun’s accuracy when subsequently fired.

The museum staff have occasionally opened the T-72 to visitors under close-supervision. This provides troops and visitors the opportunity to experience the interior of the tank and to get the real feel of being inside one. Most people are surprised to discover how compact the interior is, with the driver essentially operating the tank in a horizontal position. In July, 2021, Bob Dallison brought the Garrison Club history enthusiasts to examine the museum’s armoured fighting vehicle (AFV) collection and with the aid of a ladder, many of them took the opportunity to check out the T-72 and other vehicles on display. We will be opening other AFVs in the collection at future events and hope you will join us.

Major (Retired) Harold Skaarup, BFA, MA, CD, served as a Canadian Forces Intelligence Officer, retiring in 2011. He earned his Master’s degree in War Studies through RMC and is the Vice-president of the Friends of the NBMHM (and President of the York Sunbury Historical Society).

New Brunswick and the Trent Affair of 1861

by Gary Campbell

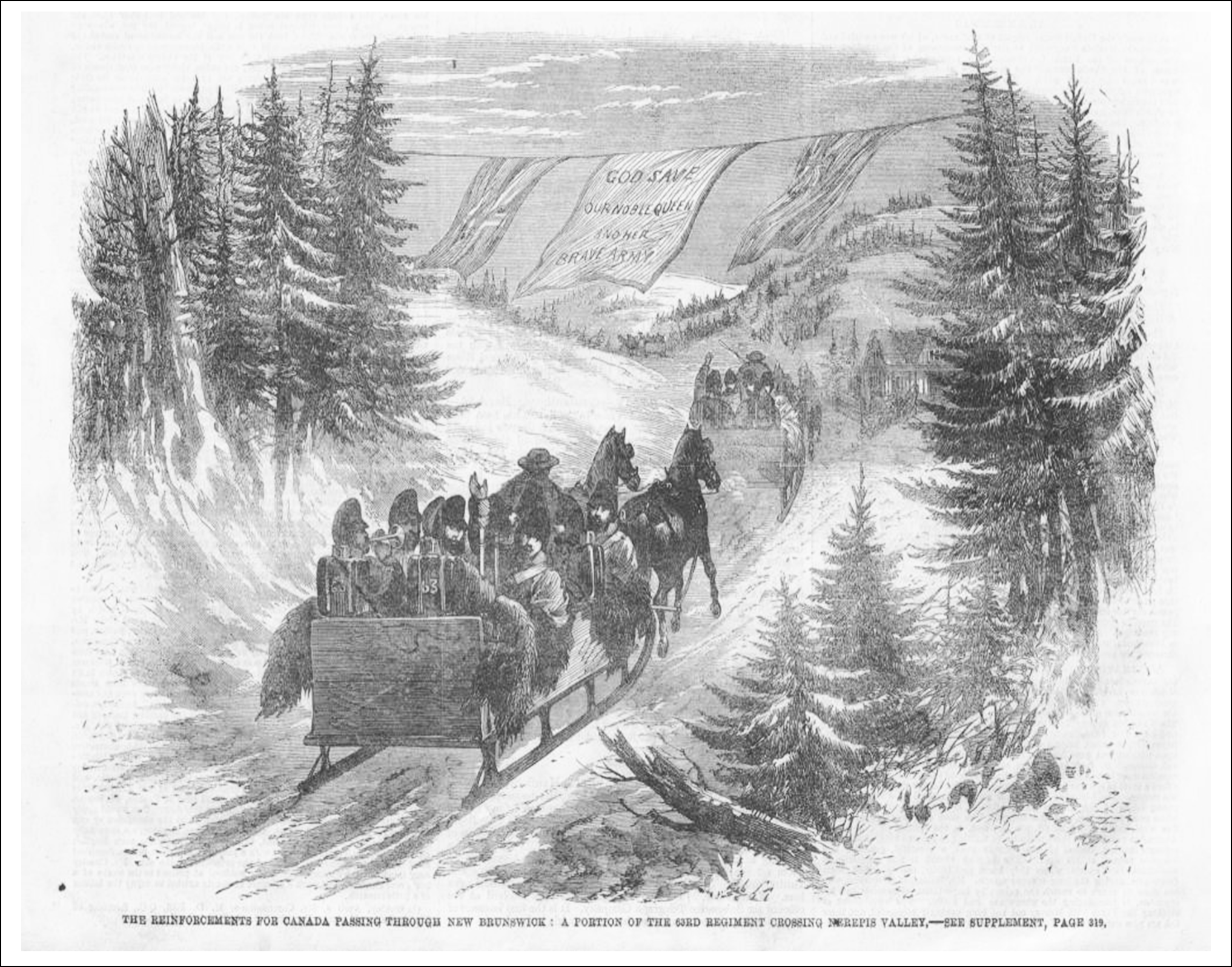

The outbreak of the American Civil War in April 1861 led to rising tensions between Great Britain and the United States. Diplomatic antagonism reached fever pitch in November 1861 after the USS Jacinto, a US Navy warship, illegally intercepted the British mail packet RMS Trent on the high seas and removed two Confederate envoys, one of whom was bound for England. While the American public delighted in the twisting of the lion’s tail, the British public was outraged. War seemed to be the likely outcome. In order to help defend British North America, a large-scale reinforcement was quickly planned. As the St. Lawrence River was closed due to ice, the troops destined for the Canadas would land in Saint John, New Brunswick and move by sleigh over the Grand Communications Route toRiviere du Loup for onwards travel by rail. By the time the deployment was over, 11,500troops had been sent to British North America of which 6,818had passed through New Brunswick to the Canadas.

British reinforcements travelling through New Brunswick in early 1862.

A great deal of planning went into this deployment. The horror of the Crimean winter of 1854/55 was still fresh in British minds. Medical experts, such as Florence Nightingale, and experienced logisticians were all consulted. However, speed was the essence. The first ship loaded with troops, equipment, and stores sailed by 7 December. A total of 16 ships were chartered, some of which made more than one voyage. The overland route was ready by the end of December and the first troops left Saint John by sleigh on 1 January 1862.

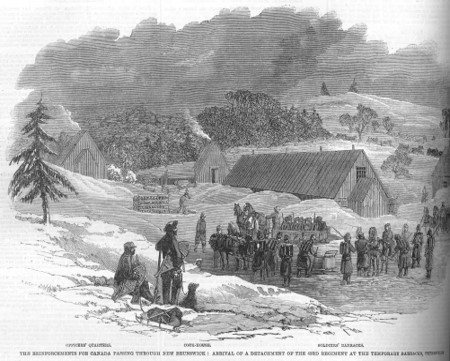

The route was divided into ten stages of about 30 miles each. Where suitable accommodations were not available, temporary camps were built such as the one at Petersville, New Brunswick. Detachments of the Military Train, Army Hospital Corps, and Commissariat Staff Corps were located at each of the staging stops. The movement of troops was regulated by telegraph.

Local contractors provided the open sleighs. The careful preplanning minimized the number of cold weather injuries. Desertion was a constant concern, and nine soldiers were lured away by American “crimps” as they travelled through New Brunswick. Fortunately, the diplomatic crisis had been resolved by late December and the Southern Commissioners had been released. This meant that the anticipated interference by American troops did not occur. This also resulted in the scaling back of the number of reinforcements.

British reinforcements arriving at Camp Petersville.

By 13 March 1862, six battalions of infantry, three field artillery and six garrison artillery batteries, two companies of engineers, two battalions of the Military Train, and detachments of the Army Hospital Corps and Commissariat Staff Corps had passed along the route.

This included the guns and equipment of the field batteries and a quantity of military stores.

The existing garrison in British North America had been reinforced by four battalions of infantry, two batteries of garrison artillery, and three field artillery batteries earlier in 1861.Four battalions of infantry, two batteries of field artillery and two of garrison artillery were added to Nova Scotia Command during the Trent Affair. This was a substantial reinforcement. Because of the relaxation in tensions, some of the troops began returning to England as soon as the summer of 1862. Those that remained, along with the militia they had trained, helped to defend British North American against the Fenian Raids four years later. The camp at Petersville is still in use.

Gary Campbell, PhD, is a retired Canadian Army Logistics officer. He has a special interest in logistics history, especially where it involves transportation. His articles on this subject have been published in several journals, both in Canada and abroad.

My articles for Friends of the NBMHM Newsletters of the past:

Battle of Hong Kong, December 1941, Newsletter March 2015

The winter of December1941 was a hard one for Canada and its allies. The Japanese attack on the Hawaiian Island of Oahu on 7 Dec took most of the headlines, but Canadians were already involved in the Pacific theatre, having sent soldiers to Hong Kong just before the conflict began. Britain had first thought of Japan as a threat with the ending of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in the early 1920s, a threat which increased with the expansion of the Sino-Japanese War. On 21 October 1938 the Japanese occupied Canton (Guangzhou) and Hong Kong was effectively surrounded. Various British Defence studies had already concluded that Hong Kong would be extremely hard to defend in the event of a Japanese attack, but in the mid-1930s, work had begun on new defences. Although Winston Churchill and his army chiefs initially decided against sending more troops to the colony, they reversed their decision in September 1941 in the belief that additional reinforcements would provide a military deterrent against the Japanese.

In the fall of 1941, the British government accepted an offer by the Canadian Government to send two infantry battalions and a brigade headquarters (1,975personnel) to reinforce the Hong Kong garrison. The Canadian battalions were the Royal Rifles of Canada from Quebec and the Winnipeg Grenadiers from Manitoba.

The Royal Rifles were serving in New Brunswick where they recruited a large number of soldiers from across the province as well as from PEI and Nova Scotia. In the fall of 1941 these soldiers were deployed to Gander, Newfoundland, where they served on Coastal Defence duties. From there they redeployed to Valcartier where they were outfitted for tropical operations. They travelled by train to the port of Vancouver where they joined up with the Winnipeg Grenadiers. These two units were formed into a formation designated as “C Force” and on 27 October they embarked on board the troopship Awatea and the armed merchant cruiser Prince Robert. They arrived in Hong Kong on 16 November 1941, but without all of their equipment as a ship carrying their vehicles was diverted to Manila at the outbreak of war.

(IWM Photo, KF 189)

Canadian soldiers on exercise in the hills on Hong Kong Island before the Japanese invasion.

The Royal Rifles had served only in Newfoundland and New Brunswick prior to their duty in Hong Kong, and the Winnipeg Grenadiers had been serving in Jamaica. As a result, many of these Canadian soldiers did not have much field experience before arriving in Hong Kong. Unfortunately, these were the soldiers who found themselves engaged in the Battle of Hong Kong which began on 8 December 1941 and ended on 25 December 1941 with the surrender of the Crown colony to the Empire of Japan. More than 100 casualties suffered by the Royal Rifles during this battle were soldiers recruited from New Brunswick.

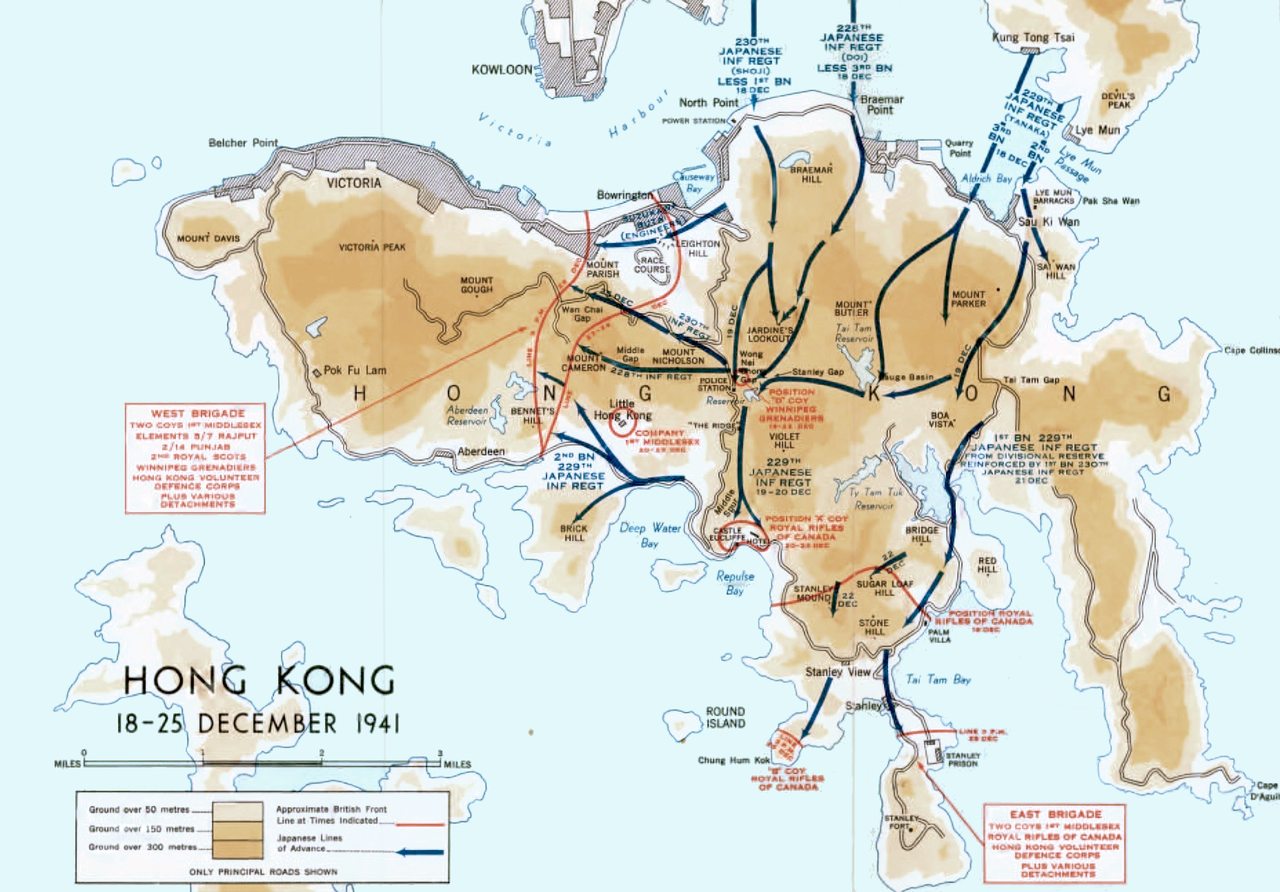

C. C. J. Bond / Historical Section, General Staff, Canadian Army – Stacey, C. P., maps drawn by C. C. J. Bond (1956) [1955]. Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War. Volume I: Six Year of War: The Army in Canada, Britain and the Pacific(PDF). (2nd rev. online ed.). Ottawa: By Authority of the Minister of National Defence. OCLC 917731527). Map compiled and drawn by Historical Section, General Staff, Canadian Army.

Map of the Battle of Hong Kong Island, 18-25 December 1941.

The Japanese attack began shortly after 08:00 on 8 December 1941 less than eight hours after the Attack on Pearl Harbor. British, Canadian and Indian forces, commanded by Major-General Christopher Maltby supported by the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps resisted the Japanese invasion by the Japanese 21st, 23rd and the38th Regiments, commanded by Lieutenant General Takashi Sakai. Some 52,000 Japanese assaulted the 14.000 Hong Kong defenders, most of whom lacked the recent combat experience of their opponents.

The colony had no significant air defence. The Commonwealth forces decided against holding the Sham Chun River which separated Hong Kong from the mainland and instead established three battalions in a defence position known as the Gin Drinkers’ Line across the hills. The Japanese 38th Infantry under the command of Major General Takaishi Sakai quickly forded the Sham Chun River by using temporary bridges. Early on 10 December1941 the 228th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel Teihichi, of the 38th Division attacked the Commonwealth defences at the Shing Mun Redoubt defended by the 2nd Battalion Royal Scots. The line was breached in five hours and later that day the Royal Scots also withdrew from Golden Hill. D company of the Royal Scots counter-attacked and captured Golden Hill. By 10:00am the hill was again taken by the Japanese. This made the situation on the New Territories and Kowloon untenable and the evacuation from them began on 11 December 1941 under aerial bombardment and artillery barrage. Where possible, military and harbour facilities were demolished before the withdrawal. By 13 December, the 5/7 Rajputs of the British Indian Army, the last Commonwealth troops on the mainland had retreated to Hong Kong Island.

MGen Maltby organised the defence of the island, splitting it between an East Brigade and a West Brigade. On 15 December, the Japanese began systematic bombardment of the island’s North Shore. Two demands for surrender were made on 13 December and 17 December. When these were rejected, Japanese forces crossed the harbour on the evening of 18 December and landed on the island’s North-East. That night, approximately 20gunners were massacred at the Sai Wan Battery after they had surrendered. There was a further massacre of prisoners, this time of medical staff, in the Salesian Mission on Chai Wan Road. In both cases, a few men survived to tell the story.

On the morning of 19 December fierce fighting continued on Hong Kong Island as the Japanese annihilated the headquarters of West Brigade. A British counter-attack could not force them from the Wong Nai Chung Gap that secured the passage between the north coast at Causeway Bay and the secluded southern parts of the island. From 20 December, the island became split in two with the British Commonwealth forces still holding out around the Stanley peninsula and in the West of the island. At the same time, water supplies started to run short as the Japanese captured the island’s reservoirs.

On the morning of 25 December, Japanese soldiers entered the British field hospital at St. Stephen’s College, and tortured and killed a large number of injured soldiers, along with the medical staff. By the afternoon of 25 December 1941, it was clear that further resistance would be futile and British colonial officials headed by the Governor of Hong Kong, Sir Mark Aitchison Young, surrendered. The garrison had held out for 17 days.

(Hong Kong Archives Photo)

228th Japanese Infantry Regiment enters Hong Kong, 8 December 1941.

The Allied dead from the campaign, including British, Canadian and Indian soldiers, were eventually interred at the Sai Wan Military Cemetery and Stanley Military Cemetery. A total of 1,528 soldiers, mainly Commonwealth, are buried there. At the end of February 1942, The Japanese government stated that numbers of prisoners of war in Hong Kong were: British 5,072, Canadian 1,689, Indian 3,829, others357, for a total of 10,947. Of the Canadians captured during the battle, 267 subsequently perished in Japanese prisoner of war camps.

Following the battle, John Robert Osborn was awarded the Victoria Cross. After seeing a Japanese grenade roll in through the doorway of the building Osborn and his fellow Canadian Winnipeg Grenadiers had been garrisoning, he took off his helmet and threw himself on the grenade, saving the lives of over 10 other Canadian soldiers.[1]

Canada responded to the outbreak of war with Japan by significantly strengthening its Pacific coastal defences, ultimately stationing more than 30,000 troops, 14 RCAF squadrons, and over 20 warships in British Columbia. Canadian forces also co-operated with the United States in clearing the Japanese from the Aleutian Islands off Alaska. Before Japan surrendered in August 1945, a Canadian cruiser, HMCS Uganda, participated in Pacific naval operations, two RCAF transport squadrons flew supplies in India and Burma, and communications specialists served in Australia.

[1] Internet:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Hong_Kong.

Battle of Hong Kong, New Brunswick Soldiers serving with the Royal Rifles of Canada

https://www.silverhawkauthor.com/post/second-world-war-battle-of-hong-kong-new-brunswick-soldiers-with-the-royal-rifles-of-canada-december-1941.

New Brunswick Units of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) in the First World War

12th Battalion, CEF

The 12thBattalion, CEF, an infantry battalion of the CEF, was authorized on 10 August 1914 and embarked for Britain on 30 September 1914, where it was redesignated the 12th Reserve Infantry Battalion, CEF on 29 April 1915,to provide reinforcements for the Canadian Corps in the field. The battalion was reduced during the summer of1916 and ultimately dissolved. Its residual strength was absorbed on 4 January 1917 into a new 12th Reserve Battalion, upon re-organization of the reserve units of the Canadian Infantry. The battalion was officially disbanded on 30 August 1920. The 12th Battalion formed part of the Canadian Training Depot at Tidworth Camp in England.

26th Battalion(New Brunswick), CEF

.jpeg)

The 26thBattalion (New Brunswick), CEF, was authorized on 7 November 1914and embarked for Britain on 15 June 1915. It arrived in France on 16 September 1915,where it fought as part of the 5th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Division in France and Flanders throughout thewar. The battalion was disbanded on 30 August 1920. (Perpetuated by the RNBR).

55th Battalion(New Brunswick & Prince Edward Island), CEF

.jpeg)

The 55th Battalion (New Brunswick & Prince Edward Island), CEF, was authorized on 7 November 1914 and embarked for Britain on 30 October 1915, where it provided reinforcements for the Canadian Corps in the field until 6July 1916, when its personnel were absorbed by the 40th Battalion (Nova Scotia), CEF. The battalion was disbanded on 21 May 1917. (Perpetuated by the RNBR).

104th Battalion, CEF

.jpeg)

The 104th Battalion, CEF, was authorized on 22 December 1915 and embarked for Britain on 28 June 1916,where it provided reinforcements for the Canadian Corps in the field until 24January 1917, when its personnel were absorbed by the 105th Battalion(Prince Edward Island Highlanders), CEF. The battalion was disbanded on 27 July 1918. (Perpetuated by the RNBR).

115th Battalion(New Brunswick), CEF

.jpeg)

The 115th Battalion (New Brunswick), CEF, was authorized on 22 December 1915and embarked for Britain on 23 July 1916, where it provided reinforcements for the Canadian Corps in the field until 21 October 1916, when its personnel were absorbed by the 112th Battalion (Nova Scotia), CEF. The battalion was disbanded on 1 September 1917. (Perpetuated by the RNBR).

132nd Battalion(North Shore), CEF

.jpeg)

The 132nd Battalion (North Shore), CEF was a unit in the CEF Force during the First World War. Based in Chatham, New Brunswick, the unit began recruiting in late 1915 in North Shore and Northumberland Counties. After sailing to England in October 1916, the battalion was absorbed into the 13th Reserve Battalion on 28 January 1917.

140th Battalion (St. John’s Tigers), CEF

The 140thBattalion (St. John’s Tigers), CEF, was authorized on 22 December1915 and embarked for Britain on 25 September 1916, where, on 2 November 1916,its personnel were absorbed by the depots of The Royal Canadian Regiment, CEF and Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, CEF to provide reinforcements for the Canadian Corps in the field. The battalion was disbanded on 27 July 1918. (Perpetuated by the RNBR).

145th Battalion (New Brunswick), CEF

.jpeg)

The 145thBattalion (New Brunswick), CEF was authorized on 22 December 1915 and embarked for Britain on 25 September 1916,where, on 7 October 1916, its personnel were absorbed by the 9th Reserve Battalion, CEF to provide reinforcements for the Canadian Corps in the field. The battalion was disbanded on 17 July 1917. (Perpetuated by the RNBR).

165th Battalion (Acadiens), CEF

%2520-%2520Copy.jpeg)

The 165th (French Acadian) Battalion, CEF was a unit in the CEF during the First World War. Based in Moncton, New Brunswick, the unit began recruiting in late 1915 throughout the Maritime provinces. After sailing to England in March 1917, the battalion was absorbed into the 13th Reserve Battalion on April 7, 1917. (Perpetuated by The North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment).

236th Battalion (New Brunswick Kilties), CEF

.jpeg)

The 236thBattalion (New Brunswick Kilties), CEF was authorized on 15 July 1916 and embarked for Britain on 30 October and 9 November 1917, where it provided reinforcements for the Canadian Corps in the field until 13 March 1918, when its personnel were absorbed by the 20th Reserve Battalion, CEF. The battalion was disbanded on 30 August 1920. (Perpetuated by the RNBR).

28thField Battery, Canadian Field Artillery, CEF

The 28th Field Battery, RCA originated in Newcastle, New Brunswick. The 28th Battery, which was authorized on 7 November 1914 as the 28th Battery, CEF, embarked for Great Britain on 9 August 1915. The battery disembarked in France on 21 January 1916, where it provided field artillery support as part of the 7th Brigade, CFA, CEF in France and Flanders until 19 March 1917, when its personnel were absorbed by the 15th and 16th Field Battery, CFA, CEF. The battery was disbanded on 1 November 1920. (Perpetuated by The North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment).

New Brunswick Regiments in Home Defence

Elements of the 62nd Regiment St. John Fusiliers, 67th Regiment Carleton Light Infantry, 71st York Regiment, and 74th Regiment The Brunswick Rangers were placed on active service on 6 August 1914 for local protective duty.

More on the CEF can be found here:

https://www.silverhawkauthor.com/post/canadian-expeditionary-force-cef-1-order-of-battle

https://www.silverhawkauthor.com/post/cancanadian-expeditionary-force-cef-2-order-of-battle-the-numbered-battalions

https://www.silverhawkauthor.com/post/canadian-expeditionary-force-cef-3-order-of-battle-the-numbered-battalions

https://www.silverhawkauthor.com/post/canadian-expeditionary-force-cef-4-order-of-battle-the-numbered-battalions

https://www.silverhawkauthor.com/post/canadian-expeditionary-force-cef-5-order-of-battle-the-numbered-battalions

Canadian Army Triumph motorcycle

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3225468)

Sergeant R.H. Easby (L) handing a message to a despatch rider, Signalman J.K. Armstrong, with his Triumph motorcycle at 5th Canadian Armoured Division Headquarters, 17 March 1944.

(Harold Skaarup Photo)

Triumph motorcycle, Canadian Army Serial No. 532176, on display in the New Brunswick Military History Museum, 5 Canadian Division Support Base Gagetown, New Brunswick.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3298166)

Sergeant Gordon Davis of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, riding a Welbike lightweight motorcycle used by airborne forces, Carter Barracks, Bulford, England, 5 January 1944.

(Author Photo)

Canadian Army folding Welbike motorcycle used by airborne forces, on display in the New Brunswick Military History Museum, 5 Canadian Division Support Base Gagetown, New Brunswick. The Welbike has the distinction of being the smallest motorcycle ever used by Commonwealth Armed Forces. Between 1942 and 1943, 3,641 units (plus a prototype and some pilot models) were built. A few were used by the British 1st and 6th Airborne Divisions and some were used at Arnhem during Operation Market Garden in the fall of 1944.

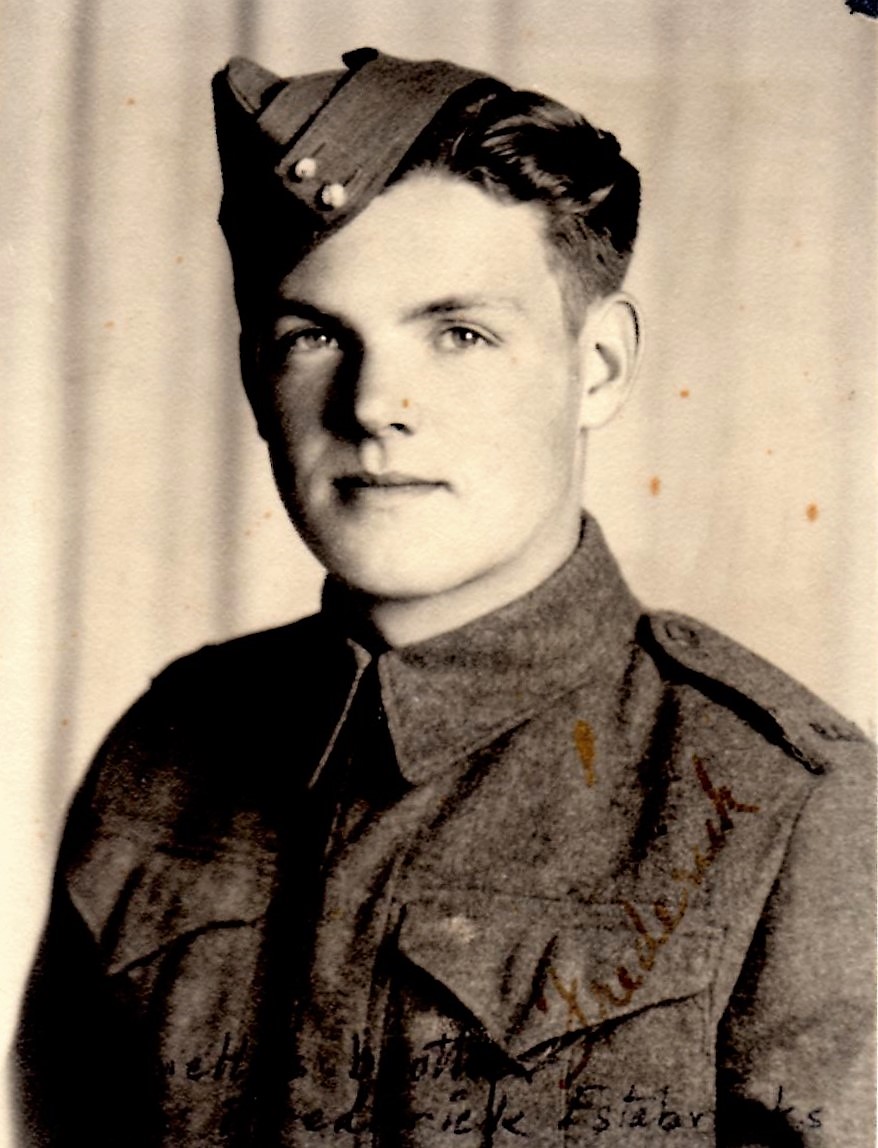

Provost Fred Estabrooks and Princess Elizabeth, Newsletter article, 10 March 2015

by Harold Skaarup

Frederick Walter Estabrooks, a retired veteran of Canadian Army Provost Corps who served in the the Second World War has passed. Fred joined the Canadian Army in 1943 at the age of 16in Woodstock, New Brunswick, did his basic training in Fredericton and then was sent to Sydney, Cape Breton, where he served on Coast Defence searchlights. Shortly afterwards he was sent to Halifax for a course in mechanics. He then sailed to the UK in May 1943 on the Queen Mary along with 20,000 other Canadian troops and landed at North Southampton. There, he joined the Military Police, No. 11 Provost Company.

During his training in England in 1943 as a Provost Corps Military Policeman, he spoke with 17-year-old Princess Elizabeth and her sister Margaret, while their father. King George VI was inspecting Canadian troops. He saw Winston Churchill while patrolling routes for convoys through the Reichswald Forest in Germany, and General Harry Crerar, Commander of the First Canadian Army. He spoke with him at a rest stop on one of the routes where directing traffic. He saw General McNaughton, and he was also in a group of Canadian troops addressed by General Bernard Montgomery in the UK and again later in Antwerp. He also he saw General Eisenhower about the same time.

Frederick went ashore at Juno Beach on 11 June, the 5th day of the landings at Normandy, with two MP sections, 26 motorcycles, and two jeeps on a landing barge. He carried a Browning 9-mm pistol. He served in the 11th Provost Company attached to 1st Canadian Army Headquarters. He rode a Harley Davidson 40/41 low clear clearance which he felt was too low and later used Matchless motorcycles. He was at Rouen with No. 4 Company riding Norton and Triumph motorcycles.

Frederick was directing traffic in the battles North of Caen in France, and lost his motorcycle to shell fire. He was attached to the No. 3Provost Company with the 3rd Canadian Division and was in the vicinity of the unfortunate bombing of the Polish Armoured forces serving under the Canadian Corps with tremendous casualties. He counted more than 200 ambulances on one of the roads he was traffic controlling, and on at least one occasion had to use his pistol to order anofficer’s staff car off the road to make way for the ambulances. His supervisor, Sergeant-Major Ray Chambers took note and approved.

On 14 November 1944 a shell hit close enough to him to destroy his motorcycle and blow him up over the cab of an oncoming truck near Nijmegen. He bounced off the hood of the cab on the truck and landed in a water-filled ditch on the other side. The German 88-mm shell took a chunk out of his right arm and pieces went through the calf of his left leg. His legs were black and blue for months, and he was sent to the Casualty Clearing Post at Cenocky sur Mer, and then to the 6th Brigade General Hospital in Antwerp for five weeks to convalesce about the time of the Battle of the Bulge through to March1945. He went on to No. 4 Provost Company with the 3rd Division in Antwerp, then to No. 13 Provost Company with II Corps. He was on traffic control duty and served as the Company Dispatch Driver in a Willys Jeep, moving up to Apeldoorn in the Netherlands and then across the border into Germany. He passed through Goch and onto Bad Zwishenheim over the next three to four weeks, where he was serving when the war ended on 8 May 1945. He then volunteered for duty in the Pacific war with Japan.

He returned to Canada at the end of July 1945 on the Isle de France at the age of 20. The war ended before he was to be deployed west. He was in Montreal for 30 days leave then went back to Saint John and then on to Fredericton where he was discharged on 21 Nov 1945. He was on train patrol from Fredericton to Newcastle for the winter of 1945-46, and was married to Joyce Taylor from Woodstock in 1946. He worked for the CPR before moved to Guelph where he met up with his former Sergeant Ray Chambers who he had served with in No. 4 Provost Company. Ray put in a good word for him with the Inspector in Guelph and Frederick was hired on with the Guelph Police Force a week later. He served with the Guelph Police Force for 30 years from Sep 1949 until his retirement as a Staff Sergeant in June 1979. He and his wife travelled in a trailer coach for four years before settling near a lake in Bobcaygeon, Ontario in 1983. Their two children Gary and Linda and their families live in Ontario. Fred passed away on 24 February 2015. He was my mother Beatrice’s older brother, and my uncle.

In 1945, Princess Elizabeth convinced her father to let her contribute directly to the war effort. Elizabeth was a member of the Auxiliary Territorial Service (the ATS), No. 230873 Second Subaltern Elizabeth Alexandra Mary Windsor, and was trained as a driver. Few of you may be aware that Britain had introduced conscription of women at the end of 1941. Elizabeth formally registered under the wartime youth service scheme in April and was given a registration card, E. D.431. By 1943, 90 per cent of single and 80 per cent of married women were in work, mostly in industry and the Armed Forces. She joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS) in the spring of 1945. She became a competent driver and was proficient in vehicle maintenance, and was enrolled on an NCO’s cadre course. The Princess’s personal contribution to service life lasted only a few months. On VE-Day, 8 May 1945, Princess Elizabeth, dressed in her ATS uniform, stood with her parents, Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Princess Margaret on the palace balcony. Later, the Princesses slipped away with young Guards officers to join the cheering crowds. They came back to stand outside the palace incognito, chanting: “We want the King, we want the King.” (Extracted from “A New Biography of the Queen”, by Sarah Bradford).

Major Raymond M. Hickey, MC, Chaplain with the North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment during the Second World War, Friends of the NBMHM Newsletter

by Harold Skaarup

One of the things about New Brunswick military history is that it is intricately tied to most of our family history. As a boy on farm in Carleton County I can remember listening to a veteran of the Second World War talking to my grandfather, a First World War veteran, about his experiences in Normandy. The man had served with the North Shore Regiment, and he was talking about the Hitler Youth boys he had fought and the hard fact that they wouldn’t surrender even when the adults had, and had to be mown down with machine gun fire. My grandfather said he was still suffering from a form of shell-shock. These days we call it post-traumatic stress. It has always been around us, even in peacetime.

When my father, RCAF Warrant Officer Aage C. Skaarup was posted to CFB Chatham, New Brunswick where he serviced the equipment that was used to start up the McDonnell CF-101B Voodoos, my mother introduced me to another veteran soldier who had been in Normandy. He was a former chaplain who had also served with the North Shore Regiment, and at that time in 1973 was living in a hospital in the town of Chatham.

The first thing I noticed as I entered his small room was a Military Cross hanging on his mirror, a fairly rare medal of bravery. I was not catholic, so calling him a father didn’t seem right. I therefore asked if I could address him as Padre or Major (Raymond Myles) Hickey and he was very pleased with that.

I had read a great deal about the war, and had many questions for him. He kindly spoke at great length about his experiences and the pride he had in having served with the men of the North Shore Regiment. He loaned me a book he had written called “The Scarlet Dawn”, which gave me much more information to add to my list of questions. His stories covered his wartime experiences from the time he did his basic training in Woodstock to his trip to England by ship and what happened when he landed in Normandy on D-Day with the first wave going into the German storm of fire. He pulled wounded men from the water as bullets splashed around him, he gave the last rites to those who weren’t going to survive, and he tended to all around him in spite of the danger. The Military Cross hanging on his mirror was well deserved, but for him, the appreciation of the men he served with was far more important.

Major Hickey stayed with his men through the horrific battles in France, Belgium, the Netherlands and on into Germany where the war ended for them. He came back to the village of Jacquet River, New Brunswick where he had been born in 1905, and where he had been ordained as a Catholic priest in 1933. He had served as a curate in Bathurst, for four years until he was appointed to the teaching staff at St. Thomas University in Chatham. When the Second World War began and Canada followed Britain in declaring war on Germany in September 1939, Father Hickey enlisted in the Canadian Army to serve as the Chaplain for the North Shore Regiment, a task he managed for six hard years. In his book, his citation includes this tribute, “His understanding and leadership of men, his keen sense of humor, and his spirit of self-sacrifice, which won him the Military Cross for bravery under enemy fire on D-Day, made him beloved and respected by all who knew him.”[1]

After the war, Reverend Hickey served as the Pastor at St. Thomas Aquinas church in Campbelton, Nova Scotia. His book The Scarlet Dawn was published in 1949. He became a Monsignor and was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Laws by his alma mater, but what he valued far more in his recollections to me was histime served with the men of the North Shore Regiment. Padre Hickey died in Chatham, now the Miramichi in 1987.

As you will find often in these newsletters, New Brunswick’s history is often our family history, and we often learn far more by word of mouth about what it was really like to have been in the service by those who were there because of it. Perhaps you have similar stories you would like to share with the Friends of the New Brunswick Military History Museum.

For those of you who would like to read a much more detailed account of Major Hickey’s service, please have a look at Melynda Jarratt’s webpage at www.CanadianWarBrides.com.

Major Raymond M. Hickey, MC

[1] Reverend Raymond Myles Hickey, The Scarlet Dawn, Tirbune Publishers Limited, Campbelton, Nova Scotia, 1940, endpapers.

5 Canadian Division Support Group Gagetown History

5 Canadian Division Support Group(5CDSG), aka Canadian Forces Base Gagetown was created at the beginning of the Cold War as a training facility for the Canadian Army which was in need of an exercise area suitable for the deployment of division-sized armoured, infantry and artillery units. Canada had just deployed two Brigades overseas, with one going to the battlefields of Korea and a second established in northern Germany to face the combined forces of the Warsaw Pact which were threatening NATO. Defence planners recognized the fact that existing facilities were relatively small, and a larger base site would need to be located relatively close to an all-season Atlantic port and have suitable railway connections. Regional economic development planners noted that the establishment of the new base in southwestern New Brunswick would provide considerable economic benefits to the province, although it would eventually come to disrupt the lives of over 900 families living in the area selected.

Following many years of construction, Camp Gagetown was officially opened in 1958, with its headquarters located near the community of Oromocto. The base occupies an expansive plateau west of the Saint John River between the cities of Fredericton and Saint John and encompasses 1,129 sq km. It was the largest military training facility in Canada and the British Commonwealth until the opening of CFB Suffield in 1971.

Initially, Camp Gagetown was the home base for many army regiments, including the Black Watch and the Royal Canadian Regiment, until defence cutbacks resulted in the removal of their parent formation, 3 Brigade Group, from the Canadian Army Order of Battle. Following the unification of the Canadian Forces on 1 February 1968, Camp Gagetown was renamed CFB Gagetown. Since that time, the base has served as the primary combat training centre for the Canadian Army, supported by 3 Area Support Group. Now 5 CDSG Gagetown. The year 2023 marks 64 years of service for both 3 ASG and CTC within our New Brunswick community.

(Harold Skaarup Photo)

Tactical Armoured Patrol Vehicle (TAPV), 5 Canadian Division Support Base Gagetown, New Brunswick.