High Flight

By John Gillespie Magee Jr.

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I’ve climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

of sun-split clouds,—and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of—wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hov’ring there,

I’ve chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air ….

Up, up the long, delirious, burning blue

I’ve topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace

Where never lark, or even eagle flew—

And, while with silent lifting mind I’ve trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space,

Put out my hand, and touched the face of God.

Notes:

This poem is in the public domain.

Copyright Credit: Magee, John Gillespie. “Letter to Parents,” September 3, 1941. John Magee Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Manuscript. In Respectfully Quoted: A Dictionary of Quotations Requested from the Congressional Research Service, ed. Suzy Platt (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1989): 117-18.

(RAF Photo)

RAF Supermarine Spitfire over Dover.

O Captain! My Captain!

by Walt Whitman

O Captain! My Captain! our fearful trip is done;

The ship has weather’d every rack, the prize we sought is won;

The port is near, the bells I hear, the people all exulting,

While follow eyes the steady keel, the vessel grim and daring:

But O heart! heart! heart!

O the bleeding drops of red,

Where on the deck my Captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead.

O Captain! my Captain! rise up and hear the bells;

Rise up—for you the flag is flung – for you the bugle trills;

For you bouquets and ribbon’d wreaths – for you the shores a-crowding;

For you they call, the swaying mass, their eager faces turning;

O captain! dear father!

This arm beneath your head;

It is some dream that on the deck,

You’ve fallen cold and dead.

My Captain does not answer, his lips are pale and still;

My father does not feel my arm, he has no pulse nor will;

The ship is anchor’d safe and sound, its voyage closed and done;

From fearful trip, the victor ship, comes in with object won;

Exult, O shores, and ring, O bells!

But I, with mournful tread,

Walk the deck my captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead.

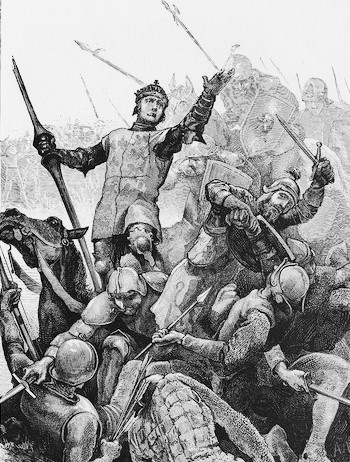

The Death of Nelson is a painting by the American artist Benjamin West dated 1806. In 1770, West painted The Death of General Wolfe. This was not an accurate representation of the event, but rather an idealisation, and it included people who were not present at the event. Nevertheless, it became very popular, and West painted at least five copies.

In 1801, three years after the Battle of the Nile, West met Horatio Nelson, who told him how much he admired the painting of Wolfe, and asked why he had not produced any more similar paintings. West, who was at the time the President of the Royal Academy, replied that he had found no subject of comparable notability. Nelson then expressed the desire that he would be the subject of West’s next similar painting. In 1805, Nelson was killed in the Battle of Trafalgar and, within six months, West had created this painting. Again it proved to be popular. When West exhibited it in his studio, within just over a month it was seen by 30,000 members of the public.

Again it was an idealisation of the subject. Although West took considerable trouble about the accuracy of details in his painting, basing the portraits on over 50 survivors of the battle, he produced, as he admitted himself, a picture “of what might have been, not of the circumstances as they happened”. West created two more paintings with Nelson as the subject, The Death of Lord Nelson in the Cockpit of the Ship “Victory” and The Immortality of Nelson, both of which are in the National Maritime Museum. West displayed the original painting at the Royal Academy Exhibition of 1811 at Somerset House.

Ozymandias, King of Kings

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desart. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

“My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

No thing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

— Percy Shelley, “Ozymandias”, 1819 edition

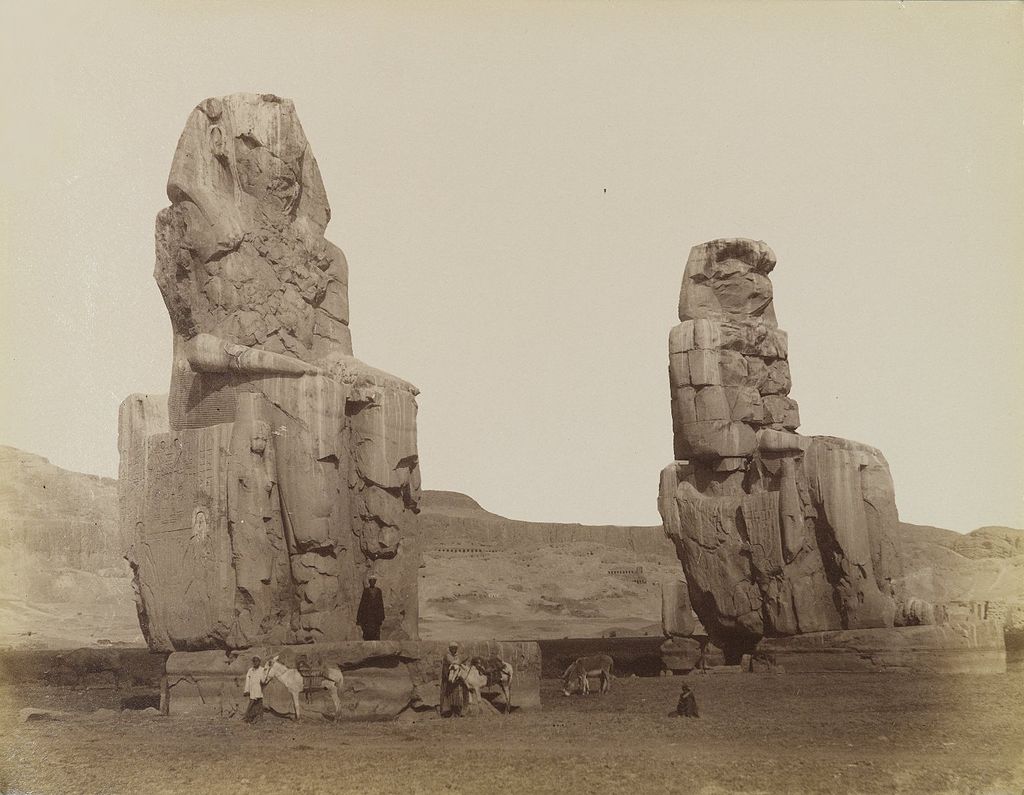

(Antonio Beato Photo)

The Colossi of Memnon (Arabic: el-Colossat or es-Salamat) are two massive stone statues of the Pharaoh Amenhotep III, which stand at the front of the ruined Mortuary Temple of Amenhotep III, the largest temple in the Theban Necropolis. They have stood since 1350 BC, and were well known to ancient Greeks and Romans, as well as early modern travelers and Egyptologists. The statues contain 107 Roman-era inscriptions in Greek and Latin, dated to between AD 20 and 250; many of these inscriptions on the northernmost statue make reference to the Greek mythological king Memnon, whom the statue was then erroneously thought to represent. Scholars have debated how the identification of the northern colossus as “Memnon” is connected to the Greek name for the entire Theban Necropolis as the Memnonium.

“Ozymandias” is a sonnet written by the English Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. It was first published in the 11 January 1818 issue of The Examiner of London. The poem was included the following year in Shelley’s collection Rosalind and Helen, A Modern Eclogue; with Other Poems, and in a posthumous compilation of his poems published in 1826. The poem was created as part of a friendly competition in which Shelley and fellow poet Horace Smith each created a poem on the subject of Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II under the title of Ozymandias, the Greek name for the pharaoh. Shelley’s poem explores the ravages of time and the oblivion to which the legacies of even the greatest are subject.

Henry Holliday, Ink and watercolour, Rammessu II, 1907.

The poem was written in 1817 and refers to Egypt’s Pharaoh Ramses II, the Elect of Ra, Keeper of Harmony, and Ruler of Rulers, also known as Ozymandias. The Ancient Greek historian Diodorus Siculus reported the following inscription on the base of one of Ozymandias’s statues: “King of Kings am I, Ozymandias. If anyone would know how great I am and where I lie, let him surpass one of my works.” Rameses II built some of the most iconic historical sites in Egypt, including the Temple of Abu Simbel, Luxor and Karnak. The earliest peace treaty ever recovered was written by Ramses II with the Hittite empire.

Abdul Abulbul Amir

The sons of the Prophet are brave men and bold

And quite unaccustomed to fear.

But the bravest by far in the ranks of the Shah

Was Abdul Abulbul Amir.

Now the heroes were plenty and well known to fame

In the troops that were led by the Tsar.

And the bravest of these was a man by the name

Of Ivan Skavinsky Skavar.

One day this bold Russian had shouldered his gun,

And donned his most truculent sneer.

Downtown he did go, where he trod on the toe

Of Abdul Abulbul Amir.

“Young man,” quoth Abdul, “Has life grown so dull,

That you wish to end your career?

Vile infidel, know, you have trod on the toe

Of Abdul Abulbul Amir.”

Said Ivan, “My friend, your remarks, in the end,

Will avail you but little, I fear.”

“For you ne’er will survive to repeat them alive.

Mr. Abdul Abulbul Amir.”

“So take your last look at sunshine and brook.

And send your regrets to the Tsar.

For by this I imply, you are going to die

Count Ivan Skavinsky Skavar.”

Then this bold Mameluke drew his trusty skibouk.

With a cry of, “Allah-Akbar!”

And with murderous intent, he ferociously went

For Ivan Skavinsky Skavar.

They fought all that night, ‘neath the pale yellow moon.

The din, it was heard from afar.

And huge multitudes came, so great was the fame,

Of Abdul and Ivan Skavar.

As Abdul’s long knife was extracting the life —

in fact he was shouting “Huzzah!”

He felt himself struck by that wily Kalmuck,

Count Ivan Skavinsky Skavar.

The Sultan drove by in his red-crested fly,

Expecting the victor to cheer.

But he only drew nigh, to hear the last sigh,

Of Abdul Abulbul Amir.

Tsar Petrovich too, in his spectacles blue,

Rode up in his new crested car.

He arrived just in time to exchange a last line,

With Ivan Skavinsky Skavar.

There’s a tomb rises up, where the blue Danube flows,

Engraved there in characters clear:

“Ah, stranger when passing, oh pray for the soul

Of Abdul Abulbul Amir.”

A Muscovite maiden her lone vigil keeps ‘Neath the light of the pale polar star And the name that she murmurs so oft as she weeps, “Abdul Abulbul Amir” is the most common name for a music-hall song written in 1877 (during the Russo-Turkish War) under the title “Abdulla Bulbul Ameer” by Irish songwriter Percy French, and subsequently altered and popularized by a variety of other writers and performers. It tells the story of two valiant heroes—the titular Abdulla, fighting for the Turks, and his foe, Ivan Skavinsky Skavar (originally named Ivan Potschjinsky Skidar in French’s version), a Russian warrior—who encounter each other, engage in verbal boasting, and are drawn into a duel in which both perish. Percy French wrote the song in 1877 for a smoking concert while studying at Trinity College Dublin. It was likely a comic opera spoof. “Pot Skivers” were the chambermaids at the college, thus Ivan “Potschjinski” Skivar would be a less than noble prince, and as Bulbul is an Arabic dialectic name of the nightingale, Abdul was thus a foppish “nightingale” amir (prince). (Wikipedia)

All For The Want Of A Nail

For want of a nail the shoe was lost.

For want of a shoe the horse was lost.

For want of a horse the rider was lost.

For want of a rider the message was lost.

For want of a message the battle was lost.

For want of a battle the kingdom was lost.

All for the want of a horseshoe nail.

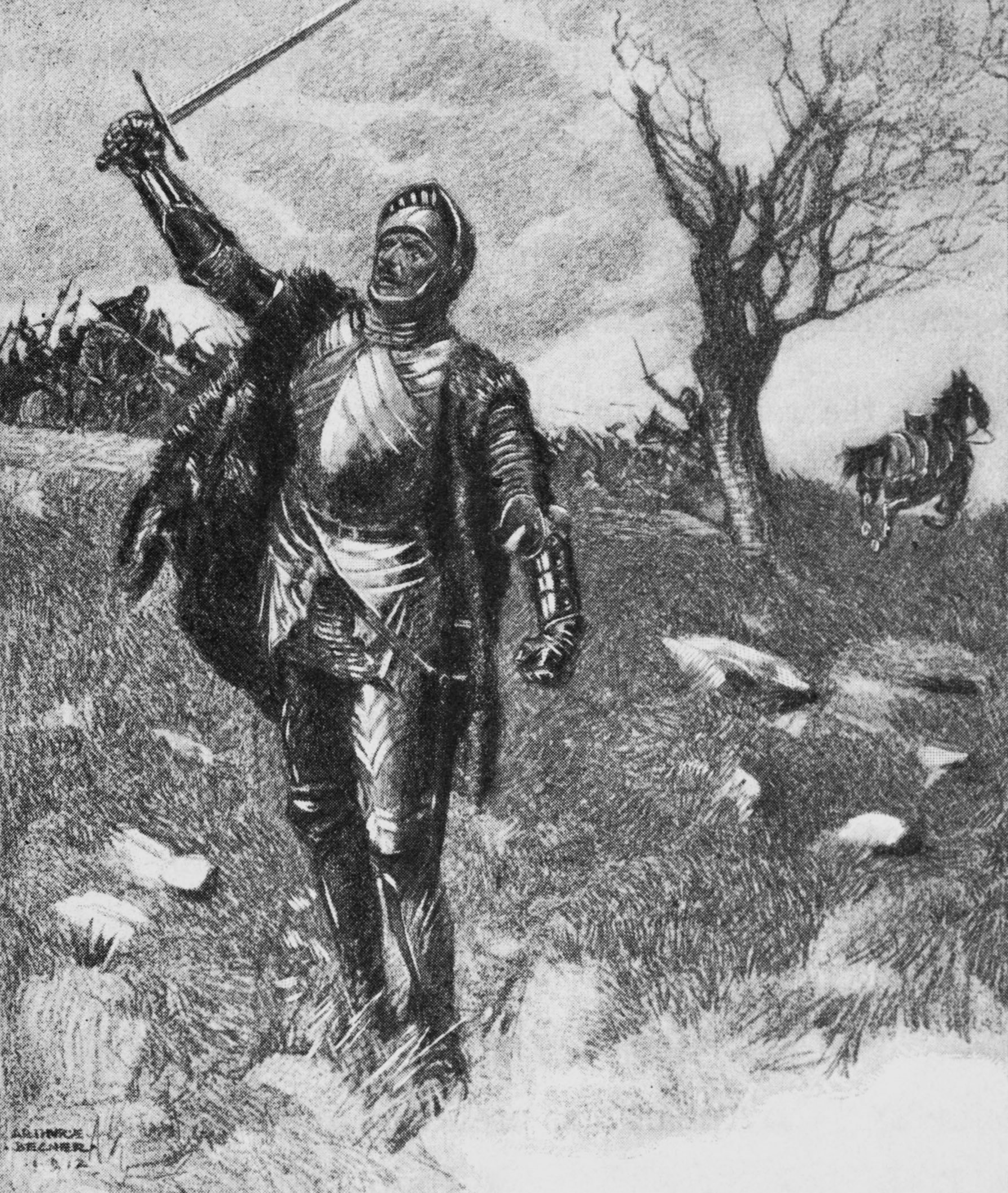

(Richard III, unhorsed during the Battle of Bosworth Field 1485 A.D.

“A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse!”

Richard III, Act 5, scene 4, line 13.

A titanic villain in Shakespeare’s history plays, Richard III departs the stage and this life with these words, fighting to his death on foot after losing his horse in battle. In that moment, the Wars of the Roses near their end. The victor in the battle, Henry Tudor, becomes Henry VII, the first of the Tudor monarchs and the founder of the Tudor dynasty.

The Charge of the Light Brigade

by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

I

Half a league, half a league,

Half a league onward,

All in the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

“Forward, the Light Brigade!

Charge for the guns!” he said.

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

II

“Forward, the Light Brigade!”

Was there a man dismayed?

Not though the soldier knew

Someone had blundered.

Theirs not to make reply,

Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to do and die.

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

III

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon in front of them

Volleyed and thundered;

Stormed at with shot and shell,

Boldly they rode and well,

Into the jaws of Death,

Into the mouth of hell

Rode the six hundred.

IV

Flashed all their sabres bare,

Flashed as they turned in air

Sabring the gunners there,

Charging an army, while

All the world wondered.

Plunged in the battery-smoke

Right through the line they broke;

Cossack and Russian

Reeled from the sabre stroke

Shattered and sundered.

Then they rode back, but not

Not the six hundred.

V

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon behind them

Volleyed and thundered;

Stormed at with shot and shell,

While horse and hero fell.

They that had fought so well

Came through the jaws of Death,

Back from the mouth of hell,

All that was left of them,

Left of six hundred.

VI

When can their glory fade?

O the wild charge they made!

All the worldwondered.

Honour the charge they made!

Honour the Light Brigade,

Noble six hundred!

The Charge of the Light Brigade by Richard Caton Woodville Jr., oil on canvas, 1894. The painting depicts the head of the charge with Lord Cardigan alongside the 17th Lancers.

The Charge of the Light Brigade was a failed military action involving the British light cavalry led by Lord Cardigan against Russian forces during the Balaclava on 25 October 1854 in the Crimean War. Lord Raglan had intended to send the Light Brigade to prevent the Russians from removing captured guns from overrun Turkish positions, a task for which the light cavalry were well suited. However, there was miscommunication in the chain of command and the Light Brigade was instead sent on a frontal assault against a different artillery battery, one well prepared with excellent fields of defensive fire. The Light Brigade reached the battery under withering direct fire and scattered some of the gunners, but they were forced to retreat immediately, and the assault ended with very high British casualties and no decisive gains.

The events were the subject of Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s narrative poem “The Charge of the Light Brigade”(1854), published just six weeks after the event. Its lines emphasise the valour of the cavalry in bravely carrying out their orders, regardless of the nearly inevitable outcome. Responsibility for the miscommunication has remained controversial, as the order was vague and Captain Louis Nolan, who delivered the written orders with some verbal interpretation, was killed in the first minute of the assault.

Be always more ready to forgive

Be always more ready to forgive, than to return an injury;

he that watches for an opportunity of revenge, lieth in

wait against himself, and draweth down mischief on his own

head.

Akhenaton? (c. B.C. 1375)

Egyptian King and Monotheist

A colossal statue of Akhenaten from his Aten Temple at Karnak. Egyptian Museum of Cairo.

Before Enlightenment

“Before enlightenment, chop wood and carry water. After enlightenment, chop wood and carry water” – Wu Li, Chinese Zen Master

…the performance of simple daily tasks can be a form of relaxing meditation.

Wu Li landscape sketch. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

May I become at all times, both now and forever

A protector for those without protection

A guide for those who have lost their way

A ship for those with oceans to cross

A bridge for those with rivers to cross

A sanctuary for those in danger

A lamp for those without light

A place of refuge for those who lack shelter

And a servant to all in need.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama

(XiQuinho Photo)

The Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region, China.

He that would be a leader must be a bridge.

—Welsh proverb

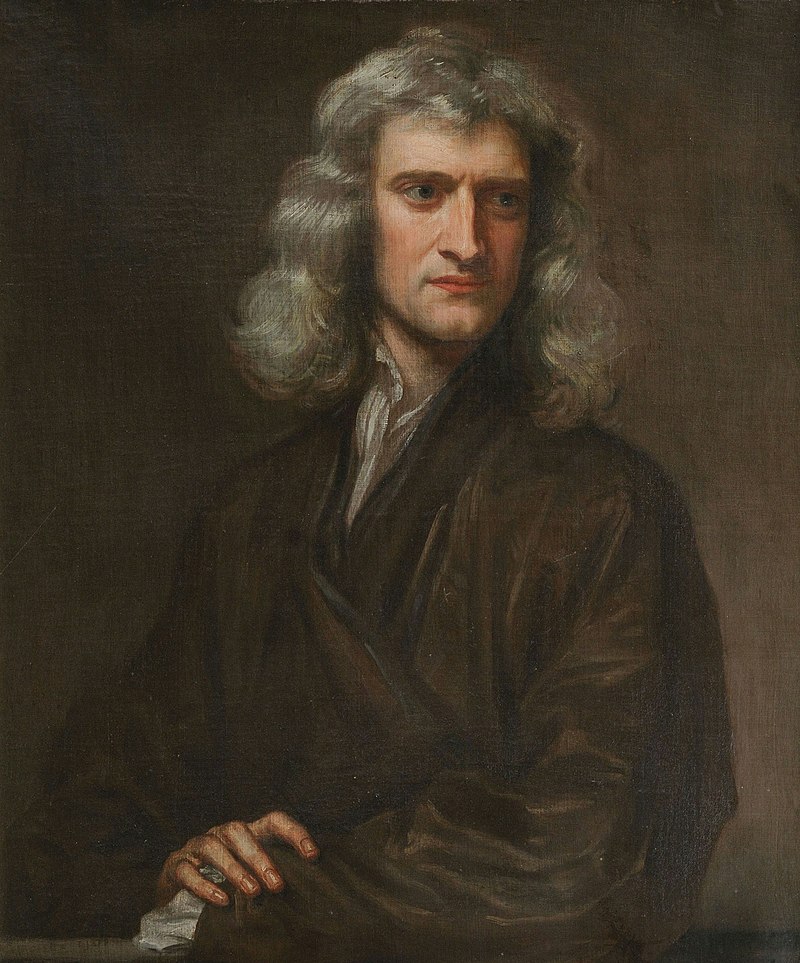

If I have been able to see farther than others, it was because I stood on the shoulders of giants.

—Sir Isaac Newton

Portrait of Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727)

Sir Isaac Newton PRS (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27)[a] was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a “natural philosopher”). He was a key figure in the philosophical revolution known as the Enlightenment. His book Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), first published in 1687, established classical mechanics. Newton also made seminal contributions to optics, and shares credit with German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz for developing infinitesimal calculus.

In the Principia, Newton formulated the laws of motion and universal gravitation that formed the dominant scientific viewpoint for centuries until it was superseded by the theory of relativity. Newton used his mathematical description of gravity to derive Kepler’s laws of planetary motion, account for tides, the trajectories of comets, the precession of the equinoxes and other phenomena, eradicating doubt about the Solar System’s heliocentricity. He demonstrated that the motion of objects on Earth and celestial bodies could be accounted for by the same principles. Newton’s inference that the Earth is an oblate spheroid was later confirmed by the geodetic measurements of Maupertuis, La Condamine, and others, convincing most European scientists of the superiority of Newtonian mechanics over earlier systems.

Newton built the first practical reflecting telescope and developed a sophisticated theory of colour based on the observation that a prism separates white light into the colours of the visible spectrum. His work on light was collected in his highly influential book Opticks, published in 1704. He also formulated an empirical law of cooling, made the first theoretical calculation of the speed of sound, and introduced the notion of a Newtonian fluid. In addition to his work on calculus, as a mathematician Newton contributed to the study of power series, generalised the binomial theorem to non-integer exponents, developed a method for approximating the roots of a function, and classified most of the cubic plane curves.

Newton was a fellow of Trinity College and the second Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge. He was a devout but unorthodox Christian who privately rejected the doctrine of the Trinity. He refused to take holy orders in the Church of England, unlike most members of the Cambridge faculty of the day. Beyond his work on the mathematical sciences, Newton dedicated much of his time to the study of alchemy and biblical chronology, but most of his work in those areas remained unpublished until long after his death. Politically and personally tied to the Whig party, Newton served two brief terms as Member of Parliament for the University of Cambridge, in 1689–1690 and 1701–1702. He was knighted by Queen Anne in 1705 and spent the last three decades of his life in London, serving as Warden (1696–1699) and Master (1699–1727) of the Royal Mint, as well as president of the Royal Society (1703–1727). (Wikipedia)

I am THE LIGHT

THE LIGHT is WITHIN me

THE LIGHT SURROUNDS me

THE LIGHT PROTECTS me…

I AM “THE LIGHT”

Consuela Newton 1996.

(Zouavman Le Zouave Photo)

Lili Marlene

Based on a German poem of 1915, this song became a favorite of both German and Allied troops during the Second World War, both in English and in the original German.

A curious example of song transcending the hatreds of war, American troops particularly liked Lili Marlene as sung by the German-born actress and singer, Marlene Dietrich.

Marlene Dietrich, photo by Don Engels.

The lyrics:

Underneath the lantern by the barrack gate, Darling I remember the way you used to wait, ‘Twas there that you whispered tenderly, That you loved me, You’d always be, My Lili of the lamplight, My own Lili Marlene.

Time would come for roll call, Time for us to part, Darling I’d caress you and press you to my heart, And there ‘neath that far off lantern light, I’d hold you tight, We’d kiss “good-night,” My Lili of the lamplight, My own Lili Marlene.

Orders came for sailing somewhere over there, All confined to barracks was more than I could bear; I knew you were waiting in the street, I heard your feet, But could not meet, My Lili of the lamplight, My own Lili Marlene.

Resting in a billet just behind the line, Even tho’ we’re parted your lips are close to mine; You wait where that lantern softly gleams, Your sweet face seems to haunt my dreams, My Lili of the lamplight, My own Lili Marlene.

Marlene Dietrich did a variation on the lyrics, probably to endear the song to the troops of the day:

…When we are marching in the mud and cold, And when my pack seems more than I can hold, My love for you renews my might, I’m warm again, My pack is light, It’s you Lili Marlene, It’s you Lili Marlene.

Listen

When I ask you to listen to me

and you start giving advice,

you have not done what I asked.

When I ask you to listen to me

and you begin to tell me why

I shouldn’t feel that way,

you are trampling on my feelings.

When I ask you to listen to me

and you feel you have to do something

to solve my problems,

you have failed me.

Strange as it may seem…

So, please, just listen and hear me.

And if you want to talk, wait a few minutes

for your turn and I promise

I’ll listen to you.

Suicide in the Trenches

by Sigfried Sasson

I knew a simple soldier boy

Who grinned at life in empty joy,

Slept soundly through the lonesome dark,

And whistled early with the lark.

In winter trenches, cowed and glum,

With crumps and lice and lack of rum,

He put a bullet through his brain.

No one spoke of him again.

You smug-faced crowds with kindling eye

Who cheer when soldier lads march by,

Sneak home and pray you’ll never know

The hell where youth and laughter go.

The Viking Prayer

Lo, there do I see my father.

Lo, there do I see my mother.

And my sisters and my brothers.

Lo, there do I see the line of my people,

back to the beginning.

Lo, they do call to me.

They bid me take my place among them,

in the Halls of Valhalla,

where the brave may live forever.

This prayer commonly known as the “Viking prayer” from the film The 13th Warrior is a fictional creation for the movie, though it is inspired by the 10th-century account of the Arab traveler Ahmad Ibn Fadlan and his observations of the Rus people. Ibn Fadlan’s account describes the death of a wealthy Rus chieftain and the grieving process, including a passage about the deceased’s family members beckoning them to the afterlife.

(Viking Armada by Edward Moran)

Naming of Parts (1942), by Harry Reed

Today we have naming of parts. Yesterday,

We had daily cleaning. And tomorrow morning,

We shall have what to do after firing. But to-day,

Today we have naming of parts. Japonica

Glistens like coral in all of the neighbouring gardens,

And today we have naming of parts.

This is the lower sling swivel. And this

Is the upper sling swivel, whose use you will see,

When you are given your slings. And this is the piling swivel,

Which in your case you have not got. The branches

Hold in the gardens their silent, eloquent gestures,

Which in our case we have not got.

This is the safety-catch, which is always released

With an easy flick of the thumb. And please do not let me

See anyone using his finger. You can do it quite easy

If you have any strength in your thumb. The blossoms

Are fragile and motionless, never letting anyone see

Any of them using their finger.

And this you can see is the bolt. The purpose of this

Is to open the breech, as you see. We can slide it

Rapidly backwards and forwards: we call this

Easing the spring. And rapidly backwards and forwards

The early bees are assaulting and fumbling the flowers:

They call it easing the Spring.

They call it easing the Spring: it is perfectly easy

If you have any strength in your thumb: like the bolt,

And the breech, and the cocking-piece, and the point of balance,

Which in our case we have not got; and the almond-blossom

Silent in all of the gardens and the bees going backwards and forwards,

For today we have naming of parts.

.303-inch Lee Enfield rifle.

Over the Hills

Though I may travel far from Spain,

a part of me shall still remain,

for you are with me night and day,

over the hills and far away…

O’er the hills and o’er the main,

through Flanders, Portugal and Spain,

King George commands and we obey,

over the hills and far away…

Then fall in lads behind the drum,

with colours blazing like the sun,

along the road to come what may,

over the hills and far away…

O’er the hills and o’er the main,

through Flanders, Portugal and Spain,

King George commands and we obey,

over the hills and far away…

Fire and shot and shell,

to the very gates of hell,

we shall stand and we shall stay,

over the hills and far away…

O’er the hills and o’er the main,

through Flanders, Portugal and Spain,

King George commands and we obey,

over the hills and far away…

…The Major marched off to carry out his tasks, while Commandante Theresa watched from her place on her horse, and smiled…

Wellington at Waterloo, by Robert Hillingford.

Protection

The only way to protect ourselves is through the strength of our consciousness. If a person is attuned to God and owns their personal power, and has self mastery over their energies, they have nothing to worry about. The world needs to wake up spiritually and psychologically, and stop being victims. It is this victim consciousness that allows them to be abducted and manipulated. If ever you sense them around, just pray, affirm, and visualize protection for yourself. Your connection with God and the Masters will bring you immediate protection.

The Tiger

William Blake

Tiger Tiger. burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye.

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

In what distant deeps or skies.

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand, dare seize the fire?

And what shoulder, & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat.

What dread hand? & what dread feet?

What the hammer? what the chain,

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? what dread grasp.

Dare its deadly terrors clasp?

When the stars threw down their spears

And watered heaven with their tears:

Did he smile His work to see?

Did he who made the lamb make thee?

Tiger Tiger burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

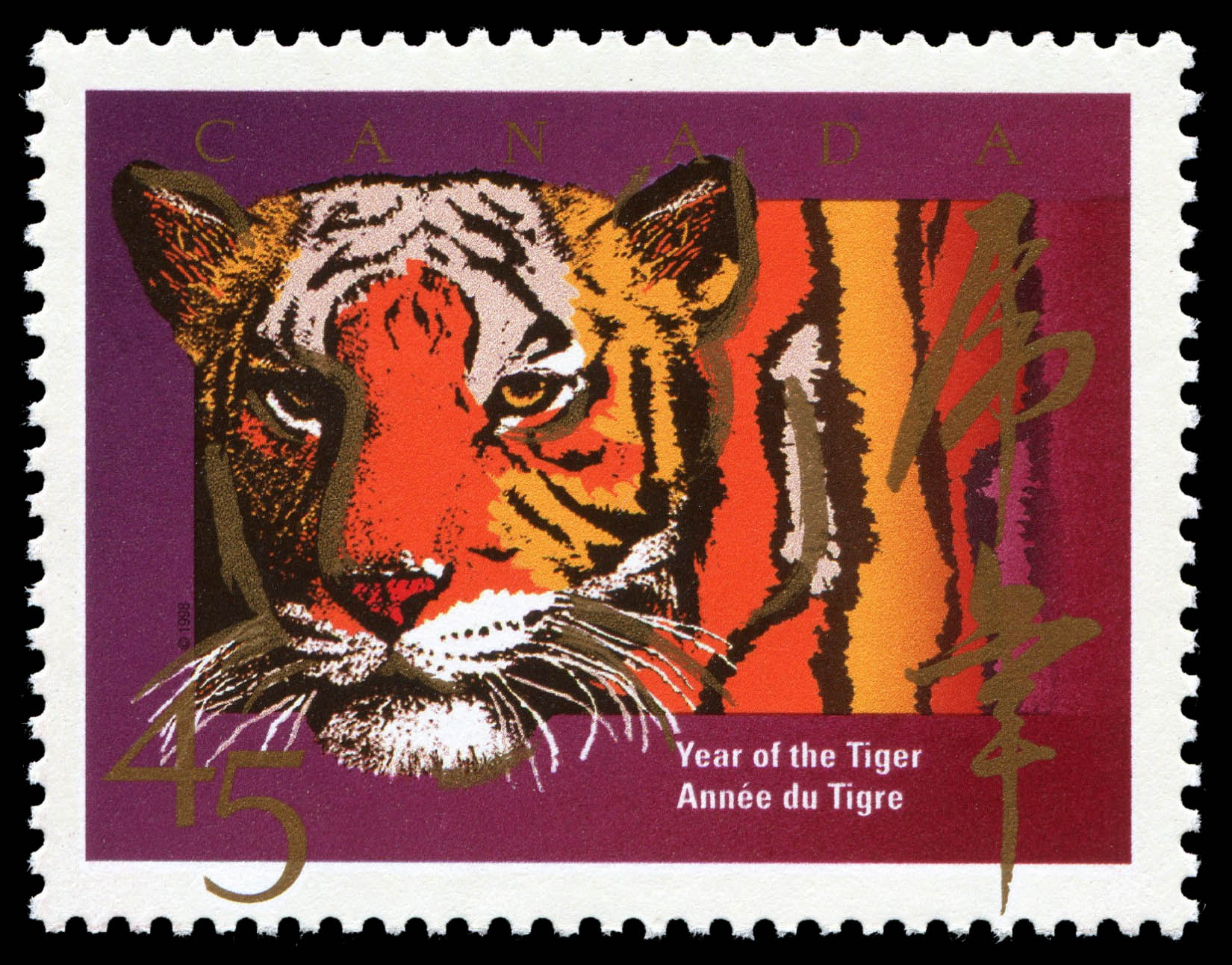

Canadian Tiger Stamp, Chinese New Year, 8 January 1998.

This Day, by Wilhelmine Estabrook-Nielsen

If you’re feeling overwhelmed

If aches and twinges have soured your attitude

While time keeps hurtling forward

And you know with all there is to do

There will never be hours enough

It’s best to climb off duty’s spinning wheel

Put on a jacket (hunter’s orange for safety)

And take a walk

To the music of bird song

On a leaf-strewn path

With two frolicking dogs

And a friend.

Then all you need to do is look up

To receive the blessing,

The breathtaking splendor

Of the day.

To be thankful for this

Miraculous gift.

This life.

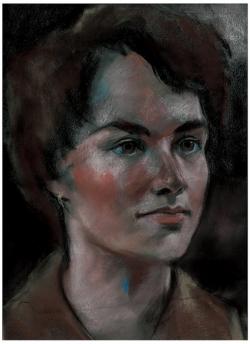

Portrait of Wilhelmine Adeline Estabrook. She passed away peacefully at her home in Wilmot, with family at her side, on Sunday, 28 February 2021. She was born 7 September 1938 and was the daughter of the late Walter and Myrtle Estabrook. Besides her parents, she was predeceased by her husband, Robert F. Neilsen; siblings, Frederick (Joyce) Estabrook, Bernard “Joe” Estabrook, Kathryn Martin; brother-in-law, Aage Skaarup. Wilhelmine is survived by two sisters, Gaynell Hawkins and Beatrice Skaarup; a sister-in-law, Ursela Estabrook; and nieces and nephews. Wilhelmine loved to tell stories and to plant trees.

Stopping by the Woods on a Snowy Evening, by Robert Frost

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

My little horse must think it queer

To stop without a farmhouse near

Between the woods and frozen lake

The darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound’s the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

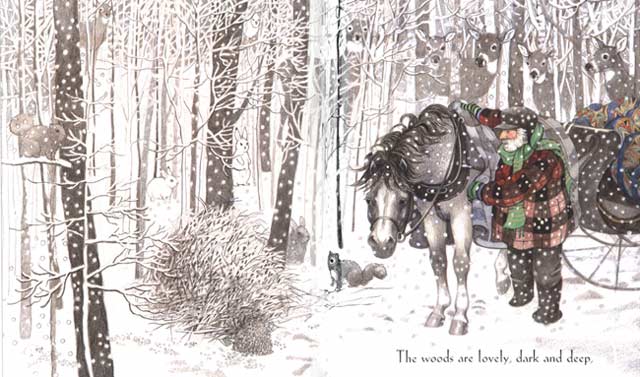

Stopping by the woods on a snowy evening.

The Road not Taken by Robert Frost

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

Do not go gentle into that good night by Dylan Thomas

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Charlemagne by Henry Wadwsorth Longfellow

Olger the Dane and Desiderio,

King of the Lombards, on a lofty tower

Stood gazing northward o’er the rolling plains,

League after league of harvests, to the foot

Of the snow-crested Alps, and saw approach

A mighty army, thronging all the roads

That led into the city. And the King

Said unto Olger, who had passed his youth

As hostage at the court of France, and knew

The Emperor’s form and face “Is Charlemagne

Among that host?” And Olger answered: “No.”

And still the innumerable multitude

Flowed onward and increased, until the King

Cried in amazement: “Surely Charlemagne

Is coming in the midst of all these knights!”

And Olger answered slowly: “No; not yet;

He will not come so soon.” Then much disturbed

King Desiderio asked: “What shall we do,

if he approach with a still greater army!”

And Olger answered: “When he shall appear,

You will behold what manner of man he is;

But what will then befall us I know not.”

Then came the guard that never knew repose,

The Paladins of France; and at the sight

The Lombard King o’ercome with terror cried:

“This must be Charlemagne!” and as before

Did Olger answer: “No; not yet, not yet.”

And then appeared in panoply complete

The Bishops and the Abbots and the Priests

Of the imperial chapel, and the Counts

And Desiderio could no more endure

The light of day, nor yet encounter death,

But sobbed aloud and said: “Let us go down

And hide us in the bosom of the earth,

Far from the sight and anger of a foe

So terrible as this!”

And Olger said:

“When you behold the harvests in the fields

Shaking with fear, the Po and the Ticino

Lashing the city walls with iron waves,

Then may you know that Charlemagne is come.

And even as he spake, in the northwest,

Lo! there uprose a black and threatening cloud,

Out of whose bosom flashed the light of arms

Upon the people pent up in the city;

A light more terrible than any darkness;

And Charlemagne appeared;–a Man of Iron

!His helmet was of iron, and his gloves

Of iron, and his breastplate and his greaves

And tassets were of iron, and his shield.

In his left hand he held an iron spear,

In his right hand his sword invincible.

The horse he rode on had the strength of iron,

And colour of iron. All who went before him

Beside him and behind him, his whole host,

Were armed with iron, and their hearts within them

Were stronger than the armor that they wore.

The fields and all the roads were filled with iron,

And points of iron glistened in the sun

And shed a terror through the city streets.

This at a single glance Olger the Dane

Saw from the tower, and turning to the King

Exclaimed in haste: “Behold! this is the man

You looked for with such eagerness!” and then

Fell as one dead at Desiderio’s feet.

Charlemagne receiving the submission of Widukind at Paderborn in 785, painted c1840 by Ary Scheffer.

Gunga Din, by Rudyard Kipling

You may talk o’ gin and beer

When you’re quartered safe out ’ere,

An’ you’re sent to penny-fights an’ Aldershot it;

But when it comes to slaughter

You will do your work on water,

An’ you’ll lick the bloomin’ boots of ’im that’s got it.

Now in Injia’s sunny clime,

Where I used to spend my time

A-servin’ of ’Er Majesty the Queen,

Of all them blackfaced crew

The finest man I knew

Was our regimental bhisti, Gunga Din,

He was ‘Din! Din! Din!

‘You limpin’ lump o’ brick-dust, Gunga Din!

‘Hi! Slippy hitherao

‘Water, get it! Panee lao,

‘You squidgy-nosed old idol, Gunga Din.’

The uniform ’e wore

Was nothin’ much before,

An’ rather less than ’arf o’ that be’ind,

For a piece o’ twisty rag

An’ a goatskin water-bag

Was all the field-equipment ’e could find.

When the sweatin’ troop-train lay

In a sidin’ through the day,

Where the ’eat would make your bloomin’ eyebrows crawl,

We shouted ‘Harry By!’

Till our throats were bricky-dry,

Then we wopped ’im ’cause ’e couldn’t serve us all.

It was ‘Din! Din! Din!

‘You ’eathen, where the mischief ’ave you been?

‘You put some juldee in it

‘Or I’ll marrow you this minute

‘If you don’t fill up my helmet, Gunga Din!’

’E would dot an’ carry one

Till the longest day was done;

An’ ’e didn’t seem to know the use o’ fear.

If we charged or broke or cut,

You could bet your bloomin’ nut,

’E’d be waitin’ fifty paces right flank rear.

With ’is mussick on ’is back,

’E would skip with our attack,

An’ watch us till the bugles made ‘Retire,’

An’ for all ’is dirty ’ide

’E was white, clear white, inside

When ’e went to tend the wounded under fire!

It was ‘Din! Din! Din!’

With the bullets kickin’ dust-spots on the green.

When the cartridges ran out,

You could hear the front-ranks shout,

‘Hi! ammunition-mules an’ Gunga Din!’

I shan’t forgit the night

When I dropped be’ind the fight

With a bullet where my belt-plate should ’a’ been.

I was chokin’ mad with thirst,

An’ the man that spied me first

Was our good old grinnin’, gruntin’ Gunga Din.

’E lifted up my ’ead,

An’ he plugged me where I bled,

An’ ’e guv me ’arf-a-pint o’ water green.

It was crawlin’ and it stunk,

But of all the drinks I’ve drunk,

I’m gratefullest to one from Gunga Din.

It was ‘Din! Din! Din!

‘’Ere’s a beggar with a bullet through ’is spleen;

‘’E’s chawin’ up the ground,

‘An’ ’e’s kickin’ all around:

‘For Gawd’s sake git the water, Gunga Din!’

’E carried me away

To where a dooli lay,

An’ a bullet come an’ drilled the beggar clean.

’E put me safe inside,

An’ just before ’e died,

‘I ’ope you liked your drink,’ sez Gunga Din.

So I’ll meet ’im later on

At the place where ’e is gone—

Where it’s always double drill and no canteen.

’E’ll be squattin’ on the coals

Givin’ drink to poor damned souls,

An’ I’ll get a swig in hell from Gunga Din!

Yes, Din! Din! Din!

You Lazarushian-leather Gunga Din!

Though I’ve belted you and flayed you,

By the livin’ Gawd that made you,

You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din!

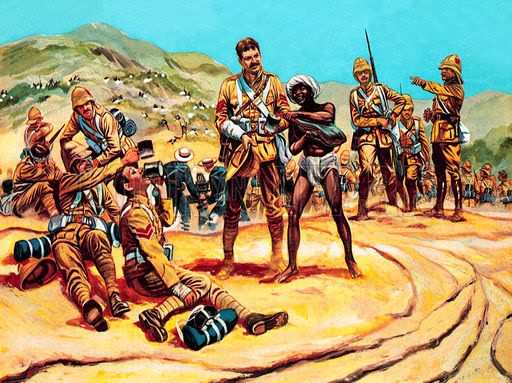

In the story-poem Gunga Din the unnamed narrator is a British soldier in the Indian Army recounting a battle in which a regimental water carrier (a bhisti) by the name of Gunga Din saved the narrator’s life at the cost of his own.

Three things

It has been said that three things increase the power of sight: gazing at greenery, gazing at beautiful faces, and gazing at flowing water. May it always be so!

یہ کہا گیا ہے کہ تین چیزیںنگاہ کی قوت کو بڑھا دیتی ہیں ، ہرے رنگ کی نگاہوں سے دیکھتی ہے ، خوبصورت چہروں کودیکھتی ہے اور بہتے ہوئے پانی کی طرف دیکھتی ہے۔ یہ ہمیشہ ایسا ہی رہے!

Trails

May your trails be crooked, winding, lonesome, dangerous, leading to the most amazing view.

And may your mountains rise into and above the clouds.

Arizona cowboys.

For all of us who lay claim to being military historians, Margaret Atwood is a great supporter:

The Loneliness of the Military Historian

By Margaret Atwood

Confess: it’s my profession

that alarms you.

This is why few people ask me to dinner,

though Lord knows I don’t go out of my way to be scary.

I wear dresses of sensible cut

and unalarming shades of beige,

I smell of lavender and go to the hairdresser’s:

no prophetess mane of mine,

complete with snakes, will frighten the youngsters.

If I roll my eyes and mutter,

if I clutch at my heart and scream in horror

like a third-rate actress chewing up a mad scene,

I do it in private and nobody sees

but the bathroom mirror.

In general I might agree with you:

women should not contemplate war,

should not weigh tactics impartially,

or evade the word enemy,

or view both sides and denounce nothing.

Women should march for peace,

or hand out white feathers to arouse bravery,

spit themselves on bayonets

to protect their babies,

whose skulls will be split anyway,

or, having been raped repeatedly,

hang themselves with their own hair.

These are the functions that inspire general comfort.

That, and the knitting of socks for the troops

and a sort of moral cheerleading.

Also: mourning the dead.

Sons, lovers, and so forth.

All the killed children.

Instead of this, I tell

what I hope will pass as truth.

A blunt thing, not lovely.

The truth is seldom welcome,

especially at dinner,

though I am good at what I do.

My trade is courage and atrocities.

I look at them and do not condemn.

I write things down the way they happened,

as near as can be remembered.

I don’t ask why, because it is mostly the same.

Wars happen because the ones who start them

think they can win.

In my dreams there is glamour.

The Vikings leave their fields

each year for a few months of killing and plunder,

much as the boys go hunting.

In real life they were farmers.

They come back loaded with splendour.

The Arabs ride against Crusaders

with scimitars that could sever

silk in the air.

A swift cut to the horse’s neck

and a hunk of armour crashes down

like a tower. Fire against metal.

A poet might say: romance against banality.

When awake, I know better.

Despite the propaganda, there are no monsters,

or none that can be finally buried.

Finish one off, and circumstances

and the radio create another.

Believe me: whole armies have prayed fervently

to God all night and meant it,

and been slaughtered anyway.

Brutality wins frequently,

and large outcomes have turned on the invention

of a mechanical device, viz. radar.

True, valour sometimes counts for something,

as at Thermopylae. Sometimes being right—

though ultimate virtue, by agreed tradition,

is decided by the winner.

Sometimes men throw themselves on grenades

and burst like paper bags of guts

to save their comrades.

I can admire that.

But rats and cholera have won many wars.

Those, and potatoes,

or the absence of them.

It’s no use pinning all those medals

across the chests of the dead.

Impressive, but I know too much.

Grand exploits merely depress me.

In the interests of research

I have walked on many battlefields

that once were liquid with pulped

men’s bodies and spangled with exploded

shells and splayed bone.

All of them have been green again

by the time I got there.

Each has inspired a few good quotes in its day.

Sad marble angels brood like hens

over the grassy nests where nothing hatches.

(The angels could just as well be described as vulgar

or pitiless, depending on camera angle.)

The word glory figures a lot on gateways.

Of course I pick a flower or two

from each, and press it in the hotel Bible

for a souvenir.

I’m just as human as you.

But it’s no use asking me for a final statement.

As I say, I deal in tactics.

Also statistics:

for every year of peace there have been four hundred

years of war.

Copyright Credit: Margaret Atwood, “The Loneliness of the Military Historian” from Morning in the Burned House. Copyright © 1995 by Margaret Atwood. Used by permission of Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

Source: Morning in the Burned House (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1995)

(Henry Palmer Photo)

Margaret Eleanor Atwood, CC, poet, novelist, critic (born 18 November 1939 in Ottawa, ON). A varied and prolific writer, Margaret Atwood is one of Canada’s major contemporary authors.

Quotable quotes

Life should not be a journey to the grave with the intention of arriving safely in a pretty and well-preserved body, but rather to skid in broadside, in a cloud of smoke, thoroughly used up, totally worn out, and loudly proclaiming “Wow! What a Ride! Hunter S Thompson.