First Nations Soldiers in the Maritime Provinces

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 5159018)

Private Patrick Joseph Augustine (Tjopatlig), Mi’kmaq traditional chief of the Big Cove Reserve, Big Cove, New Brunswick, serving with the 1st Battalion, Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada, with the Canadian NATO Brigade, ca 1960.

(Author Photo)

Elder Charles Solomon, New Brunswick First Nations combat veteran of the Second World War, giving a sweet grass blessing at the site of the St. Mary’s Reserve on the Saint John River, 14 May 2009.

First Nations Military History in the Maritimes

There are approximately 16,246 First Nations people in New Brunswick, with 15 reserves including 9,781, primarily Maliseet and Mi’kmaq, on reserve and 6,465 off reserve. (Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada’s Indian Register System, 31 Dec 2019)

There are 13 First Nation communities in Nova Scotia. Spread over 42 reserves and settlements, these communities range from Acadia First Nation in the southwest to Membertou First Nation in northeastern Cape Breton. In 2018 there were 19,090 registered Mi’kmaq living in Nova Scotia with 10,878 living on reserve. Eight of these communities are on mainland Nova Scotia, and five are in Cape Breton.

There are two Mi’kmaq First Nations reserves on Prince Edward Island. Lennox Island First Nation – L’nui Mnikuk – is located in western Prince Edward Island and has a total population of 952 (on and off-reserve). Lennox Island is served by a Chief and three Councillors (2 representing on-reserve and 1 representing off-reserve). Abegweit First Nation – Epekwitk – is composed of 3 reserves: Morell, Rocky Point, and Scotchfort. In 2016, Abegweit First Nation had a total population of 375. Abegweit is served by a Chief and two Councillors. Mi’kmaw know the island as ‘Epekwitk’, meaning “lying in the water”.

Mi’kmaq is a plural noun that means “the people.” The singular version of the word, used to refer to one person, ends in a “w” – Mi’kmaw. Members of the Mi’kmaq historically referred to themselves as Lnu but used the term níkmaq (my kin) as a greeting.

Archaeologist Dean Snow says that the deep linguistic split between the Mi’kmaq and the Eastern Algonquians to the southwest suggests the Mi’kmaq developed an independent prehistoric sequence in their territory. It emphasized maritime orientation, as the area had relatively few major river systems. The Mi’kmaq lived in an annual cycle of seasonal movement between living in dispersed interior winter camps and larger coastal communities during the summer. The weapon used most for hunting was the bow and arrow. The Mi’kmaq made their bows from maple.

The Mi’kmaq territory was the first portion of North America that Europeans exploited at length for resource extraction. Reports by John Cabot, Jacques Cartier, and Portuguese explorers about conditions there encouraged visits by Portuguese, Spanish, Basque, French, and English fishermen and whalers, beginning in the early years of the 16th century. Early European fishermen salted their catch at sea and sailed directly home with it. But they set up camps ashore as early as 1520 for dry-curing cod. During the second half of the century, dry curing became the preferred preservation method. These European fishing camps traded with Mi’kmaq fishermen; and trading rapidly expanded to include furs. By 1578 some 350 European ships were operating around the Saint Lawrence estuary. Most were independent fishermen, but increasing numbers were exploring the fur trade.

The Mi’kmaq territory was divided into seven traditional districts. Each district had its own independent government and boundaries. The independent governments had a district chief and a council. The council members were band chiefs, elders, and other worthy community leaders. The district council was charged with performing all the duties of any independent and free government by enacting laws, justice, apportioning fishing and hunting grounds, making war and suing for peace.

The Mi’kmaq were one of the first Indigenous peoples in Canada to have regular contact with Europeans. The French colonized parts of their land in the 17th century. On 24 June 1610, Grand Chief Membertou converted to Catholicism and was baptised. He concluded an alliance with the French Jesuits which affirmed the right of Mi’kmaq to choose Catholicism andor Mi’kmaq tradition. The Mi’kmaq, as trading allies with the French, were amenable to limited French settlement in their midst.

While the Mi’kmaq and French had mostly friendly relations, the arrival of the British resulted in frequent warfare, as France and England were engaged in imperial wars during this time.

(Author Photo)

First Nations birch bark canoe, courtesy of King’s Landing via Evelyn Fidler, on display in the New Brunswick Military History Museum.

Mi’kmaq Warrior.

The Mi’kmaq, many of whom had converted to Roman Catholicism, sided with the French in these conflicts. Following the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), France surrendered mainland Nova Scotia to the British under the Treaty of Utrecht (1713). This happened without the knowledge of the Mi’kmaq, who did not believe they had surrendered their land to the French in the first place.

During continued warfare between the British and Mi’kmaq, a series of peace agreements were signed, including the Peace and Friendship Treaties of 1725, 1752 and 1760–61. However, unlike the later Numbered Treaties, these agreements did not concern the surrender of land. Mi’kmaq in Nova Scotia therefore continue to claim Aboriginal title (ownership) to the province, in addition to their reserves.

British-Mi’kmaq conflict formerly ended after the “Burying of the Hatchet Ceremony”, an event that took place on 25 June 1761 during the signing of the Peace and Friendship Treaties. “Burying the hatchet” is a phrase commonly used to refer to the ending of a feud. During the 1761 ceremony, those who signed the treaties celebrated by dancing and singing.

Allied with the French, the first nations of the Wabanaki Confederacy of Acadia fought six colonial wars against the British and their native allies, including the French and Indian Wars, Father Rale’s War and Father Le Loutre’s War.

Mi’kmaq militias were made up of Mi’kmaq warriors (smáknisk) who worked independently as well as in coordination with the Wabenaki Confederacy, French and Acadian forces throughout the colonial period to defend their homeland Mi’kma’ki against the English (the British after 1707).

War was central to the way of life of many First Nation cultures, and a persistent reality in all regions although it waxed in intensity, frequency and decisiveness. The causes were complex and often interrelated, springing from both individual and collective motivations and needs. At a personal level, young males often had strong incentives to participate in military operations, as brave exploits were a source of great prestige in most Aboriginal cultures. According to one Jesuit account from the 18th Century, ‘The only way to attract respect and public veneration among the Illinois is, as among the other Savages, to acquire a reputation as a skilful hunter, and particularly as a good warrior … it is what they call being a true man.’ At a community level, warfare played a multifaceted role, and was waged for different reasons. Some conflicts were waged for economic and political goals, such as gaining access to resources or territory, exacting tribute from another nation or controlling trade routes. Revenge was a consistent motivating factor across North America, a factor that could lead to recurrent cycles of violence, often low intensity, which could last generations. Among the Iroquoian nations in the northeast, ‘mourning wars’ were practiced. Such conflicts involved raiding with the intent to capture prisoners, who were then adopted by bereaved families to replace family members who had died prematurely due to illness or war.

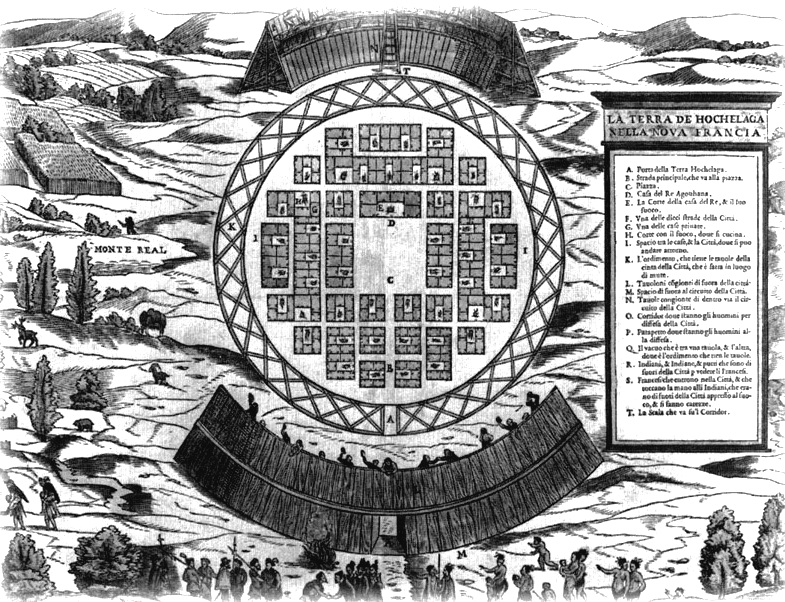

(Library and Archives Canada (C-10489))

Hochelaga ca 1535.

Archaeological evidence confirms the prominent role of warfare in indigenous societies well before the arrival of permanent European settlers. As early as the year 1000, for example, Huron, Neutral, Petun and Iroquois villages were increasingly fortified by a timber palisade that could be nearly 10 metres in height, sometimes villages built a second or even third ring to protect them against attacks by enemy nations. Craig Keener has described how these structures became larger and more elaborate through to the 1500s, with logs as large as 24 inches in diameter being used to construct the multi-layered defences, an enormous investment in communal labour that the villagers would not have made had it not been deemed necessary. Sieges and assaults on such fortified villages therefore must have occurred before Europeans arrived, and were certainly evident in the 17th and 18th Centuries. War also fuelled the development of highly complex political systems among these Iroquoian nations. The great confederacies, such as the Iroquois Confederation of Five Nations and the Huron Confederacy, probably created in the late 16th Century, grew out of their members’ desire to stem the fratricidal wars that had been ravaging their societies for hundreds of years. They were organized around the Confederacy Council, which ruled on inter-tribal disputes in order to settle differences without bloodshed. The Councils also discussed matters of foreign policy, such as the organization of military expeditions and the creation of alliances.

The Iroquois Confederacy, also known as the Haudenosaunee, is a Native American confederation consisting of six different tribes: the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora. The confederacy was founded sometime around the 12th century, and is believed to be the oldest surviving participatory democracy in the world.The confederacy was created as a way for the six tribes to unite and work together towards common goals, such as defense against outside threats.

In 1609, the French explorer Samuel de Champlain fought a battle against the Iroquois, alongside his Montagnais allies. According to his detailed account of the encounter, the military practices were highly ritualistic and governed by strict rules. For example, when the two groups met on the shores of Lake Champlain, they negotiated the time at which the battle would take place. They decided to ‘wait until day to recognize each other and as soon as the sun rose’ they would wage battle. ‘The entire night was spent in dancing and singing,’ reports Champlain, with the two camps shouting ‘an infinite number of insults’ and threats at each other. When the sun rose, the armies, each made up of more than 200 warriors, faced each other in close ranks and approached calmly and slowly, preparing to join combat. All the warriors were armed with bows and arrows, and wore armour made of wood and bark woven with cotton. When Champlain and two other French soldiers opened fire with their arquebuses, they killed the three main Iroquois chiefs and the enemy retreated. Finally, hand-to-hand combat was engaged and the allies of the French captured 10 or 12 prisoners.

Europeans were less likely to witness the more common and more deadly raiding and ambushes that characterised the indigenous way of war across the continent. In the northeast woodlands and elsewhere, the advent of European firearms would quickly render such open field combat too costly according to indigenous cultural norms of war. After 1609, most observers reported that Aboriginal people did ‘not know how to fight in open country,’ and accounts of Aboriginal warfare usually described hit and run military techniques, which the French called ‘la petite guerre.’ This was essentially a form of guerrilla warfare, the primary goal of which was to inflict casualties, capture prisoners and take scalps, while suffering as few losses as possible. To do so, the warriors generally moved in small groups and took pains to catch the enemy unawares or encircle to encircle them, while eluding the same tactics by the other side. They took advantage of the terrain to remain concealed and ambush the enemy, or slipped into a camp by night to surprise the occupants in their sleep. Once they had achieved their objective, the warriors retreated before a counter-attack could be mounted.

While it suited conditions in the forests of North America, Aboriginal guerrilla warfare was far removed from European methods of the time. To Europeans, who believed that rigid discipline was essential to produce a soldier capable of producing maximum fire through massed formation in the open, the Aboriginal warriors generally seemed to be undisciplined fighters without any sense of tactics. Moreover, “skulking” behind trees was viewed as cowardly, and actually aiming, particularly at officers, was unsporting and barbaric.

Aboriginal warriors had a high regard for their own tactics, and were themselves often dismissive of Europeans modes of combat, which they considered courageous folly. For example, Makataimeshekiakiak (Black Sparrowhawk), a Sauk war chief who fought in the War of 1812, wrote: Instead of taking every opportunity to kill the enemy and preserve the lives of their own men (which among us is considered sound policy for a war chief), they advance in the open and fight, with no regard for the number of warriors they may lose! When the battle is over, they withdraw to celebrate and drink wine, as if nothing had happened, after which they set down a written declaration on what they have done, each side claiming victory! And neither of the two records half the dead in his own camp. They all fought bravely but would be no match for us at war. Our maxim is ‘kill the enemy and save our own men.’ These [white] chiefs are fine for paddling a canoe but not for steering it.

When the Europeans arrived, the main offensive weapon of a warrior in north-eastern America, was the bow and arrow. The arrowhead was usually made of bone or flaked stone. When they attacked a village, the warriors sometimes used burning arrows and some nations, such as the Erie, were even known to use poisoned arrows. The bow was slightly less than two metres long and powerful enough to propel an arrow more than 120 metres. However, the bow and arrow was most effective at short distances. In 1606, an arrow that passed through the dog he was holding in his arms killed a French sailor. Warriors were therefore taught to approach the enemy and let fly a volley of arrows before the adversary had time to react. The hatchet, better known by the Algonquin name ‘tomahawk,’ and the war club (a bludgeon of approximately 60 cm usually made of a very hard wood and ending in a large ball) were used in hand-to-hand combat to knock down the opponent, who was then often finished off with a knife.

Aboriginal peoples quickly adopted European firearms. While the early arquebuses were less effective than the bow and arrow, since they were ‘too cumbersome and too slow,’ they had the advantage of emitting a thunderous noise when fired, frightening the enemy and making him more vulnerable. While a few Aboriginal peoples did manage to get their hands on firearms in the early 17th Century, it was not until the 1640s that they began acquiring them on a large scale. They quickly mastered the new technology and became more skilful in handling the weapons than their European counterparts. Indeed, Patrick Malone has argued that the Algonquian speaking tribes of New England also became keen judges of the technology. They quickly recognised the disadvantages of matchlock muskets, and began demanding the more expensive flintlocks, which better suited their hunting and ‘skulking way of war.’ Use of the bow and arrow continued for many years, especially in surprise attacks in which the sound of a gun firing would have alerted the enemy, but by the early 18th Century, most northeastern First Nation were using the musket for hunting and combat.

Some aspects of indigenous warfare shocked the European settlers. For example, the custom of scalping the enemy, which consisted in removing his hair by cutting off his scalp, scandalized many European observers. While some scholars have suggested that the Europeans themselves during first contact introduced this practice, it now appears certain that scalping existed well before colonization. In 1535, the explorer Jacques Cartier saw five scalps displayed in the village of Hochelaga. But while they acted indignant about the practice, the whites encouraged their allies to engage in it. In the 1630s, the British began offering a reward for the scalps of their enemies, the French followed suit in the 1680s. According to ethno-historians James Axtell and William Sturtevant, it was the Europeans (particularly the British settlers) who adopted the practice of scalping after contact with the Aboriginal peoples, prompted by the often attractive rewards paid by the colonial authorities. (DND, DDH Notes)

The Mi’kmaq militias deployed effective resistance for over 75 years before the Halifax Treaties were signed (1760–61). In the nineteenth century, the Mi’kmaq “boasted” that, in their contest with the British, the Mi’kmaq “killed more men than they lost”. In 1753, Charles Morris stated that the Mi’kmaq have the advantage of “no settlement or place of abode, but wandering from place to place in unknown and, therefore, inaccessible woods, is so great that it has hitherto rendered all attempts to surprise them ineffectual”. Leadership on both sides of the conflict employed standard colonial warfare, which included scalping non-combatants (e.g., families). After some engagements against the British during the American Revolution, the militias were dormant throughout the nineteenth century, while the Mi’kmaq people used diplomatic efforts to have the local authorities honour the treaties.

In 1763, following the end of the Seven Years War, the British issued a Royal Proclamation. It defined the relationship between the Crown and Indigenous people and claimed to protect Indigenous territory from settlers. In practice, however, White settlement continued. Twenty years later, the British government began granting land to the Mi’kmaq. The first designated “Indian Reserves” were created in 1801, followed by more in 1820 (the year Cape Breton was incorporated into the colony) and 1821.

In his review of these lands in 1843, Joseph Howe, then Nova Scotia’s commissioner for Indian Affairs, noted that reserves had been created on poor-quality lands. The reserves were also vulnerable to intrusion by settlers. By the mid-19th century, the Mi’kmaw population in Nova Scotia had declined to around 1,500. (Estimates have placed the pre-contact Mi’kmaq to anywhere between 3,500 and 6,000 people.)

After confederation, Mi’kmaq warriors eventually joined Canada’s war efforts in both World Wars. The most well-known colonial leaders of these militias were Chief (Sakamaw) Jean-Baptiste Cope and Chief Ètienne Bâtard. Chief Bâtard fought in Father Le Loutre’s War and he participated in fighting the British in the Battle of Chignecto and the Attack at Jeddore.

Jean Baptiste Cope (Kopit in Mi’kmaq meaning ‘beaver’) was also known as Major Cope, a title he was probably given from the French military, the highest rank given to Mi’kmaq. Cope was the sakamaw (chief) of the Mi’kmaq of Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia. He maintained close ties with the Acadians along the Bay of Fundy, speaking French and being Catholic. During Father Le Loutre’s War, Cope participated in both military efforts to resist the British and efforts to create peace with the British. During the French and Indian War, he was at Miramichi, New Brunswick, where he is presumed to have died during the war. Cope is perhaps best known for signing the Treaty of 1752 with the British, which was upheld in the Supreme Court of Canada in 1985 and is celebrated every year along with other treaties on Treaty Day (1 October). Cope was born in Port Royal and the oldest child of six.

The Dummer’s War (1722–1725, also known as Father Rale’s War, Lovewell’s War, Greylock’s War, the Three Years War, the 4th Anglo-Abenaki War, or the Wabanaki-New England War of 1722–1725), was a series of battles between New England and the Wabanaki Confederacy (specifically the Mi’kmaq. Maliseet and Abenaki) who were allied with New France. The eastern theatre of the war was fought primarily along the border between New England and Acadia in Maine as well as in Nova Scotia; the western theatre was fought in northern Massachusetts and Vermont at the border between Canada (New France) and New England. (During this time, Massachusetts included Maine and Vermont.)

The root cause of the conflict on the Maine frontier concerned the border between Acadia and New England, which New France defined as the Kennebec River in southern Maine. Mainland Nova Scotia came under British control after the Siege of Port Royal in 1710 and the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 (not including Cape Breton Island), but present-day New Brunswick and Maine remained contested between New England and New France. New France established Catholic missions among the four largest Indian villages in the region: one on the Kennebec River (Norridgewock), one farther north on the Penobscot River (Penobscott Indian Island Reservation), one on the Saint John River (Meductic Indian Village/Fort Meductic, and one at Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia (Saint Anne’s Mission). Similarly, New France established three forts along the border of New Brunswick during Father Le Loutre’s War to protect it from a British attack from Nova Scotia.

The Treaty of Utrecht ended Queen Anne’s War, but it had been signed in Europe and had not involved any member of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Abenaki signed the 1713 Treaty of Portsmouth, but none had been consulted about British ownership of Nova Scotia, and the Mi’kmaq began to make raids against New England fishermen and settlements. The war began on two fronts as a result of the expansion of New England settlements along the coast of Maine and at Canso, Nova Scotia. The New Englanders were led primarily by Massachusetts Lt. Governor William Dummer, Nova Scotia Lt. Governor John Doucett, and Captain John Lovell. The Wabanaki Confederacy and other Indian tribes were led primarily by Father Sébastien Rale, Chief Gray Lock, and Paugus.

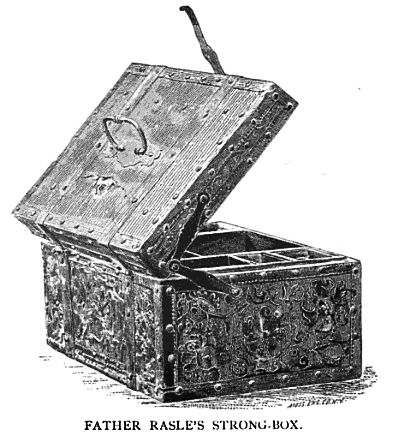

Governor Shute was convinced that the French were behind Wabanaki claims, so he sent a military expedition under the command of Colonel Thomas Westbrook of Thomaston to capture Father Rale in January 1722. Most of the tribe was away hunting, and Westbrook’s 300 soldiers surrounded Norridgewock to capture Rale, but he was forewarned and escaped into the forest. They found Rale’s strongbox among his possessions, however, which contained a secret compartment. Inside that compartment they found letters implicating Rale as an agent of the government of Canada, promising Indians enough ammunition to drive the Colonists from their settlements.

(William Goold – From the book Portland in the Past (1886), p. 180)

Father Rale’s strongbox with a secret compartment.

Shute reiterated English claims of sovereignty over the disputed areas in letters to the Lords of Trade and to Governor General Philippe de Rigaud Vaudreuil of New France. Vaudreuil pointed out in response that France claimed sovereignty over the area, while the Wabanakis maintained possession, and he suggested that Shute misunderstood the way in which European ideas of ownership differed from those of the Indians.

In response to the raid on Norridgewock, on 13 June 1722, the Abenakis raided Fort George which was under the command of Captain John Gyles. They burned the homes of the village and took 60 prisoners, most of whom were later released.

On 15 July 1722, Father Lauverjat from Penobscot led 500-600 Indians from Penobscot and Medunic (Maliseet) and laid siege to Fort St. George for 12 days. They burned a sawmill, a large sloop, and sundry houses, and killed many of their cattle. Five New Englanders were killed and seven were taken prisoner, while the New Englanders killed 20 Maliseet and Penobscot warriors. After the raid, Westbrook was given command of the fort. Following this raid, Brunswick was raided again and burned before the warriors returned to Norridgewock.

In response to the New England attack on Father Rale at Norridgewock in March 1722, 165 Mi’kmaq and Maliseet troops gathered at Minas (Grand Pre, Nova Scotia) to lay siege to Annapolis Royal. Lieutenant Governor John Doucett took 22 Mi’kmaqs hostage in May 1722 to prevent the provincial capital from being attacked. In July, the Abenakis and Mi’kmaqs blockaded Annapolis Royal with the intent of starving the capital. The Indians captured 18 fishing vessels and prisoners in raids from Cape Sable Island to Canso. They also seized prisoners and vessels working in the Bay of Fundy.

On 25 July 1722, Governor Shute formally declared war on the Wabanakis. Lieutenant Governor William Dummer conducted the Massachusetts involvement in the war, since Shute sailed for England at the end of 1722 to deal with ongoing disputes that he had with the Massachusetts colonial assembly.

During Father Rale’s War, at the young age of 28, Jean Baptiste Cope was probably one of several Mi’kmaq who signed the peace treaty, which ended the war between the New Englanders and the Mi’kmaq. During King William’s War, Cope was a leader in the Shubenacadie region. There were between 50-150 Mi’kmaq families and a few Acadian farms in the river valley close to the principal Mi’kmaq village named Copequoy. The village had become the site of a Catholic mission in 1722. (The location became a site of two major annual events, All Saints Day and Pentecost, which attracted Mi’kmaq from great distances.)

On 10 Sep 1722, between 400 and 500 St. Francis (Odanak, Quebec) and Mi’kmaq Indians attacked Arrosic, Maine in conjunction with Father Rale at Norridgewock. Captain Penhallow discharged musketry from a small guard, wounding three of the Indians and killing another. This defence gave the inhabitants of the village time to retreat into the fort, leaving the Indians in full possession of the village. They slaughtered 50 head of cattle and set fire to 26 houses outside the fort, then assaulted the fort, killing one New Englander but otherwise making little impression.

That night, Col. Walton and Capt. Harman arrived with 30 men, to which were added approximately 40 men from the fort under Captains Penhallow and Temple. The combined force of 70 men attacked the Indians, but they were overwhelmed by their numbers. The New Englanders then retreated into the fort. The Indians eventually retired up the river, viewing further attacks on the fort as useless.

During their return to Norridgewock, the Indians attacked Fort Richmond with a three-hour siege. They burned homes and killed cattle, but the fort held. Brunswick and other settlements near the mouth of the Kennebec were destroyed.

On 9 March 1723, Colonel Thomas Westbrook led 230 men to the Penobscot River and traveled approximately 32 miles (51 km) upstream to the Penobscot Village. They found a large Penobscot fort some 70 by 50 yards (64 by 46 m), with 14-foot (4.3 m) walls surrounding 23 wigwams. There was also a large chapel (60 by 30 feet [18.3 by 9.1 m]). The village was vacant, and the soldiers burned it to the ground.

The Wabanaki Confederacy of Acadia orchestrated a total of 14 raids against towns along the border of New England throughout 1723, primarily in Maine. The campaign started in April and lasted until December, during which 30 people were killed or taken captive. The Indian attacks were so fierce along the Maine frontier that Dummer ordered residents to evacuate to the blockhouses in the spring of 1724.

During the spring of 1724, the Wabanaki Confederacy orchestrated ten raids on the Maine frontier which killed, wounded, or imprisoned more than 30 New Englanders. In Kennebunk harbour, a sloop was taken, and the whole crew was put to death.

In the spring of 1724, the command of St. George’s Fort at Thomaston was given to Capt. Josiah Winslow, older brother of John Winslow. On 30 April 1724, Winslow and Sergeant Harvey and 17 men left George’s Fort in two whale boats and went downriver several miles to Green Island. The following day, the two whale boats became separated and approximately 200 to 300 Abenakis descended on Harvey’s boat, killing Harvey and all his men except three Indian guides who escaped to the Georges Fort. Captain Winslow was then surrounded by 30 to 40 canoes which came off from both sides of the river and attacked him with great fury. After hours of fighting, Winslow and his men were killed except for three friendly Indians who escaped back to the fort. The Tarrantine Indians were reported to have lost over 25 warriors.

On 27 May at Purpooduck, the Indians killed one man and wounded another. On the same day, a man was killed at Saco. In June, Indians raided Dover, New Hampshire and Elizabeth Hanson wrote her captivity narrative.

The Indians also engaged in a naval campaign, assisted by the Mi’kmaqs from Cape Sable Island. In just a few weeks, they had captured 22 vessels, killing 22 New Englanders and taking more prisoner. They also made an unsuccessful siege of St. George’s Fort.

In the second half of 1724, the New Englanders launched an aggressive campaign up the Kennebec and Penobscot rivers. On 22 Aug, Captains Jeremiah Moulton and Johnson Harmon led 200 Rangers to Norridgewock to kill Father Rale and destroy the settlement. There were 160 Abenakis, many of whom chose to flee rather than fight. At least 31 chose to fight, and most of them were killed. Father Rale was killed in the opening moments of the battle, a leading chief was killed, and nearly two dozen women and children.

The Colonists had casualties of two militiamen and one Mohawk. Harmon destroyed the Abenaki farms, and those who had escaped were forced to abandon their village and move northward to the Abenaki village of St. Francis and Bécancour, Quebec. New England took over much of the Maine territory. In New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, the treaty that ended Father Rale’s war marked a significant shift in European relations with the Mi’kmaq and Maliseet tribes.

Captain John Lovell made three expeditions against the Indians. On the first expedition in Dec 1724, he and his militia company of 30 men (often called “snowshoe men”) left Dunstable, New Hampshire, trekking to the north of Lake Winnipesaukee (“Winnipiscogee Lake”) into the White Mountains of New Hampshire. On 10 Dec 1724, they and a company of rangers killed two Abenakis. In February 1725, Lovewell made a second expedition to the Lake Winnipesaukee area. On 20 Feb, his force came across wigwams at the head of the Salmon Falls River in Wakefield, New Hampshire, where ten Indians were killed.

Lovewell’s third expedition consisted of 46 men and left from Dunstable on 16 April 1725. They built a fort at Ossipee, New Hampshire and garrisoned it with 10 men, including a doctor and John Goffe, while the rest left to raid the |Pequawket tribe at Fryeburg, Maine. On 9 May, the militiamen were being led in prayer by chaplain Jonathan Frye when a lone Abenaki warrior was spotted. Lovewell and his men closed in on the warrior, leaving their packs behind in a clearing. Shortly after they left, their packs were discovered by a Pequawket war party led by Chief Paugus, who set up an ambush in anticipation of their eventual return.

Lovewell and his men caught up with the warrior and exchanged gunfire. Lovewell and one of his men were wounded in the encounter, and the Indian was killed by Ensign Seth Wyman, Lovewell’s second in command. Lovewell’s force then returned to their packs and the ambush was sprung. Lovewell and eight of his men were killed and two were wounded when the Pequawkets opened fire. The survivors managed to retreat to a strong position and fended off repeated attacks until the Pequawkets withdrew around sunset. Only 20 of the militiamen survived the battle; three died on the return journey. The Pequawket losses included Chief Paugus. The battle was the last major engagement between the English and the Wabanaki Confederacy and Governor Dummer’s War.

(Engraving from John Gilmary Shea A Child’s History of the United States Hess and McDavitt 1872)

Chamberlaine and Paugus at Lovewell’s Fight.

Nova Scotia’s governor launched a campaign to end the Mi’kmaq blockade of Annapolis Royal at the end of July 1722. They retrieved over 86 New England prisoners taken by the Indians. One of these operations resulted in the Battle of Winnepang (Jeddore Harbour), in which 35 Indians and five New Englanders were killed. Only five Indian bodies were recovered from the battle, and the New Englanders decapitated the corpses and set the severed heads on pikes surrounding Canso’s new fort.

During the war, a church was erected at the Catholic mission in the Mi’kmaq village of Shubenacadie (Saint Anne’s Mission). In 1723, the village of Canso was raided again by the Mi’kmaqs, who killed five fishermen, so the New Englanders built a 12-gun blockhouse to guard the village and fishery.

The worst moment of the war for Annapolis Royal came on 4 July 1724 when a group of 60 Mi’kmaqs and Maliseets raided the capital. They killed and scalped a sergeant and a private, wounded four more soldiers, and terrorized the village. They also burned houses and took prisoners. The New Englanders responded by executing one of the Mi’kmaq hostages on the same spot where the sergeant was killed. They also burned three Acadian houses in retaliation. As a result of the raid, three blockhouses were built to protect the town. The Acadian church was moved closer to the fort so that it could be more easily monitored. In 1725, sixty Abenakis and Mi’kmaqs launched another attack on Canso, destroying two houses and killing six people.

Penobscot tribal chiefs expressed a willingness to enter peace talks with Lieutenant Governor Dummer in December 1724. They were opposed in this by French authorities, who continued to encourage the conflict, but Massachusetts Lieutenant Governor Dummer announced a cessation of hostilities on 31 July 1725 following negotiations in March. The terms of this preliminary agreement were negotiated by Dummer and Chiefs Loron and Wenemouet and applied only to the Penobscots at first. They could retain Jesuit priests, but the two parties disagreed concerning land titles and British sovereignty over the Wabanakis. The written agreement was translated into Abenaki by French Jesuit Etienne Lauverjat; Chief Loron immediately repudiated it, specifically rejecting claims of British sovereignty over him.

Despite his disagreement, Loron pursued peace, sending wampum belts to other tribal leaders, although his envoys were unsuccessful in reaching Gray Lock, who continued his raiding expeditions. Peace treaties were signed in Maine on 15 Dec 1725 and in Nova Scotia on 15 June 1726, involving many tribal chiefs. The peace was reconfirmed by all except Gray Lock at a major gathering at Falmouth in the summer of 1727; other tribal envoys claimed that they were not able to locate him. Gray Lock’s activity came to an end in 1727, after which time he disappears from English records.

As a result of the war, the Indian population declined on the Kennebec and Penobscot Rivers, and western Maine came more strongly under British control. The terms of Dummer’s Treaty were restated at every major new treaty conference for the next 30 years, but there was no major conflict in the area until King George’s War in the 1740s.

In New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, Dummer’s Treaty marked a significant shift in British relations with the Mi’kmaqs and Maliseets, who refused to declare themselves British subjects. The French lost their footholds in Maine, while New Brunswick remained under French control for several years. The peace in Nova Scotia lasted for 18 years. The British took control of New Brunswick at the end of Father Le Loutre’s War, with the defeat of Le Loutre at Fort Beauséjour. This was the only war fought by the Wabanakis against the British on their own terms and for their own reasons, rather than in support of French interests. The final major battle of the war was the Battle of Pequawket, or “Lovewell’s Fight”.

Le Loutre took over the Shubenacadie mission in 1737. During King William’s War, Cope and Le Loutre worked together in several engagements against the British forces. At the outbreak of Father Le Loutre’s War, the Catholic missionary began to lead the Mi’kmaq and Acadian Exodus out of peninsular Nova Scotia to settle in French-ruled territory. Dozens of Mi’kmaq from Shubenacadie accepted Le Loutre’s offer and followed him to the Isthmus of Chignecto. Cope and at least ninety other Mi’kmaq, however, refused to abandon their homes on the Shubenacadie. While Cope may have initially not supported the French initiatives, he would quickly reconsider after Edward Cornwallis established Halifax.

By unilaterally establishing Halifax, the Mi’kmaq believed that the British were violating earlier treaties (1726). He tried to set up peace treaties but failed. Cornwallis offered a bounty to New England Rangers for the scalps of Mi’kmaq families just as the French had offered a bounty to the Mi’kmaq for the scalps of British families. At the same time the British were adopting an uncomplicated, racially based view of local politics, several leaders of the Micmac community were developing a similar stance. According to historian Geoffery Plank, both combatants understood their conflict as a “race war”, and that the Mi’kmaq and British were “single-mindedly” determined to drive each other from the peninsula of Nova Scotia.

After the establishment of Halifax, Cope seems to have joined Father Le Loutre at the Isthmus of Chignecto. Through a series of raids, while stationed in this region, Cope and the other Mi’kmaq war leaders were able to confine the new settlers to the vicinity of Halifax. British plans to scatter Protestants across peninsular Nova Scotia were temporarily undermined.

After the Battle of Chignecto on 3 Sep 1750, Le Loutre and the French retreated to Beausejour ridge and Lawrence began to build Fort Lawrence on the former Acadian community of Beaubassin. Almost a month after the battle, on 15 Oct, Cope, disguised in a French officer’s uniform, approached the British under a white flag of truce and killed Captain Edward Howe.

After eighteen months of inconclusive fighting, uncertainties and second thoughts began to disturb both the Mi’kmaq and the British communities. By the summer of 1751 Governor Cornwallis began a more conciliatory policy. For more than a year, Cornwallis sought out Mi’kmaq leaders willing to negotiate a peace. He eventually gave up, resigned his commission and left the colony.

With a new Governor in place, Governor Peregrine Hopson, the first and only willing Mi’kmaq negotiator was Cope. On 22 Nov 1752, Cope finished negotiating a peace for the Mi’kmaq at Shubenacadie. The basis of the treaty was the one signed in Boston which closed Father Rale’s War (1725). Cope tried to get other Mi’kmaq chiefs in Nova Scotia to agree to the treaty but was unsuccessful. The Governor became suspicious of Cope’s actual leadership among the Mi’kmaq people. Of course, Le Loutre and the French were outraged at Cope’s decision to negotiate at all with the British.

In retaliation for the Attack at Country Harbour, on the night of 21 April (19 May), under the command of Major Cope, Mi’kmaq warriors attacked a diplomatic team made up of Captain Bannerman and his crew in the area of Jeddore, Nova Scotia. On board were nine English men and one Anthony Casteel, who was the pilot and spoke French. The Mi’kmaq killed the English and let Casteel off at Port Toulouse, where the Mi’kmaq sank the schooner after looting it.

As the war continued, on 23 May 1753, Cope burned the peace treaty of 1752. The peace treaty signed by Cope and Hobson had not lasted six months. Shortly after, Cope joined Le Loutre again and worked to convince Acadians to join the exodus from the peninsula portion of Nova Scotia.

After the experience with Cope, the British were less willing to trust Mi’kmaq efforts for peace that followed over the next two years. Future peace treaties also failed because the Mi’kmaq proposals always included land claims, which the British presumed was tantamount to giving land to the French. In the Action of 8 June 1755, a naval battle off Cape Race, Newfoundland, 10,000 scalping knives for Acadians and Indians serving under Chief Cope and Acadian Beausoleil were found on board the French ships Alcide and Lys, for use as they continued to fight Father Le Loutre’s War.

During the French and Indian War, Lawrence declared another bounty on scalps of male Mi’kmaq. Cope was probably among the Mi’kmaq and the Algonquian allies who helped Acadians evade capture during the Saint John River Campaign. According to Louisbourg account books, from 1756 to 1758, the French made regular payments to Cope and other natives for British scalps. Cope is reported to have gone to Miramichi, New Brunswick, in the area where French Officer Boishebert had his refugee camp for Acadians escaping the deportation. He is likely to have died in the region before 1760.

Tradition indicates that during the French and Indian War, Lahave Chief Paul Laurent and a party of eleven invited Shubenacadie Chief Jean-Baptiste Cope and five others to St. Aspinquid’s (in present-day Point Pleasant park, Halifax) to negotiate peace with the British. Chief Paul Laurent had just arrived in Halifax after surrendering to the British at Fort Cumberland on 29 Feb 1760. In early March 1760, the two parties met and engaged in armed conflict. Chief Larent’s party killed Cope and two others, while Chief Cope’s party killed five of the British supporters. Shortly after Cope’s death, Mi’kmaq chiefs signed a peace treaty in Halifax on 10 March 1760. Chief Laurent signed on behalf of the Lahave tribe and a new chief, Claude Rene, signed on behalf of the Shubenacadie tribe. (During this time of surrender and treaty making, tensions among the various factions who were allied against the British were evident. For example, a few months after the death of Cope, the Mi’kmaq militia and Acadian militias made the rare decisions to continue to fight despite losing the support of the French priests who were encouraging surrender.)

After the treaty of 1752, while the conflict continued, the British never returned to their old policy of driving the Mi’kmaq off the peninsula. The treaty signed by Cope and Governor Hobson was upheld in 1985 Supreme Court. Currently there is a monument to the Peace Treaty on the Shubenacadie Reserve. The descendants of Cope gave Cope’s gun to the Citadel Hill (Fort George) museum of Parks Canada. (Source: Wikipedia, including “Anthony Casteel’s Journal”. Collection de documents inédits sur le Canada et l’Améuqye (Tome Deuxieme ed.). Quebec: L.-J. Demers et Freres. 1889. pp. 111–126.

Between 1775 and 1815, British agents worked to make the First Nations into military allies of the British, providing supplies, weapons, and encouragement. During the American Revolutionary Ear (1775–1783) most of the tribes supported the British. In 1779, the Americans launched a campaign to burn the villages of the Iroquois in New York State. The refugees fled to Fort Niagara and other British posts and remained permanently in Canada. Although the British ceded the Old Northwest to the United States in the Treaty of Paris in 1783, it kept fortifications and trading posts in the region until 1795. The British then evacuated American territory, but operated trading posts in British territory, providing weapons and encouragement to tribes that were resisting American expansion into such areas as Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois and Wisconsin. Officially, the British agents discouraged any warlike activities or raids on American settlements, but the Americans became increasingly angered, and this became one of the causes of the War of 1812.

In the war, the great majority of First Nations supported the British, and many fought under the aegis of Tecumseh. But Tecumseh died in battle in 1813 and the Indian coalition collapsed. The British had long wished to create a neutral Indian state in the American Old Northwest and made this demand as late as 1814 at the peace negotiations at Ghent. The Americans rejected the idea, the British dropped it, and Britain’s Indian allies lost British support. In addition, the Indians were no longer able to gather furs in American territory. Abandoned by their powerful sponsor, Great Lakes-area natives ultimately assimilated into American society, migrated to the west or to Canada, or were relocated onto reservations in Michigan and Wisconsin. Historians have unanimously agreed that the Indians were the major losers in the War of 1812.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2851179)

1842 Medal presented to Joseph M. Itkobeitch, Chief of the Micmac First Nations at Restigouche, New Brunswick.

(Library and Archives Canada Photos, MIKAN No. 2851184)

1872 Medal, presented to Dominion of Canada First Nations Chiefs (Northwest Territories), Replacement Medal for first medal to commemorate Treaty numbers 1 and 2 (Queen Victoria)

(Library and Archives Canada Photos, MIKAN No. 2851193)

1873-1899 Medal presented to First Nations Chiefs to commemorate Treaty Numbers 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 (Queen Victoria).

Confederation in 1867 and the passage of the Indian Act in 1876 put further strain on Mi’kmaw society. The federal government established residential schools to assimilate Indigenous peoples throughout Canada. The Mi’kmaq and other Indigenous peoples in the Maritimes were sent to the Shubenacadie residential school in Nova Scotia, which operated from 1930 to 1967. However, the government found it challenging to administer services to a small population. Therefore, in 1942, Indian Affairs initiated a policy of centralization: all Mi’kmaq were encouraged to move to one of two reserves, one on the mainland (Shubenacadie) and one in Cape Breton (Eskasoni). Sipekne’katik (formerly Shubenacadie) and Eskasoni remain the most populous reserves on the mainland and Cape Breton, respectively.

Except for self-governing communities, the federal government has some level of control over reserves through the Indian Act. First Nation communities in Nova Scotia each receive funding from the government through annual “contribution agreements.”

First World War

More than 4000 Indigenous men volunteered for overseas service with the(CEF) in the First World War. Modern historians and other researchers have show that a few thousand more Indigenous soldiers volunteered without self-identifying as Indigenous on their recruitment forms. Historian Timothy Winegard has revealed that recruitment and volunteerism of Indigenous soldiers breaks down into three phases. In the first phase, from August 1914 to December 1915, the Army “unofficially” accepted Indigenous soldiers, particularly Status Indians (en with legal Indian status). In other words, they allowed them to enlist but did not actively recruit them. In the second phase, from December 1915 to December 1916, the Canadian government and the Department of Indian Affairs relaxed restrictions against Indigenous volunteers as casualties grew for the CEF after deadly battles like the Second Battle of Ypres (1915) and the Battle of the Somme (1916). The third phase took place from 1917 to the end of the war. In the third phase, Indigenous volunteers were officially encouraged as voluntary enlistment dried up across Canada and Prime Minister Robert Borden decided to institute (mandatory military service). The Military Service Act (MSA) of August 1917, which declared conscription of men aged 20-45, initially included all Indigenous men (except for Inuit men), regardless of their legal Indian status. Although First Nations and other Indigenous men were exempted from the MSA in January 1918, many more continued to volunteer through the end of the war. It is estimated that more than 1200 Indigenous soldiers were killed or wounded in the First World War (https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/first-world-war-wwi)

During the First World War, First Nations enlistment was remarkably high in several Aboriginal communities inthe Maritimes. Nearly half of eligible Mi’kmaq and Maliseet men in Atlantic Canada enlisted. Every eligible male from the Mi’kmaq reserve near Sydney, Nova Scotia, volunteered. New Brunswick bands sent 62 out of 116 eligible males to the front, and 30 of 64 eligible PEI Indians joined. Although Newfoundland and Labrador remained a separate colony during the world wars, an estimated fifteen men from Labrador with Inuit ancestry served with The Royal Newfoundland Regiment in the British Army.

The statistics from Quebec are somewhat sketchy, but also suggest a high enlistment rate. In Ontario, all but three eligible men from the Algonquin of Golden Lake band enlisted, and approximately 100 Anishnawbe (Ojibwa) men from isolated communities in northern Ontario travelled to Port Arthur (Thunder Bay) to sign up. The Six Nations of the Grand River Reserve provided more soldiers than any other Indian community in the country: approximately 300. In Manitoba, 20 men from the Peguis band saw frontline service – an impressive statistic considering that the total adult male population was only 118. Sadly, eleven never made it home. Similarly, The Pas Band, Sioux Band at Griswold, and St. Peter’s Band all sent more than twenty percent of their adult male population overseas. More than half of the eligible adult males on the Cote Reserve in Saskatchewan served overseas. 29 Alberta Indians served, with 17 men volunteering from the Blood Reserve. In British Columbia, every male member of the Head of the Lake band between the ages of twenty and thirty-five enlisted. These cases are exemplary by any measure. Men who lived in the Territorial North seldom volunteered because they pursued a subsistence lifestyle and had little information about or connection to international developments, but a few – such as John Campbell, who ventured three thousand miles by trail, canoe and steamer to enlist in Vancouver – joined the war effort. ‘It must … be borne in mind,’ D.C. Scott explained at war’s end, ‘that a large part of the Indian population, located in remote and inaccessible locations, were unacquainted with the English language and were, therefore, not in a position to understand the character of the war, its cause or effect.’ This made the high levels of Aboriginal enlistment even more remarkable. (http://www.cmp-cpm.forces.gc.ca/dhh-dhp/pub/boo-bro/abo-aut/chapter-chapitre-05-eng.asp)

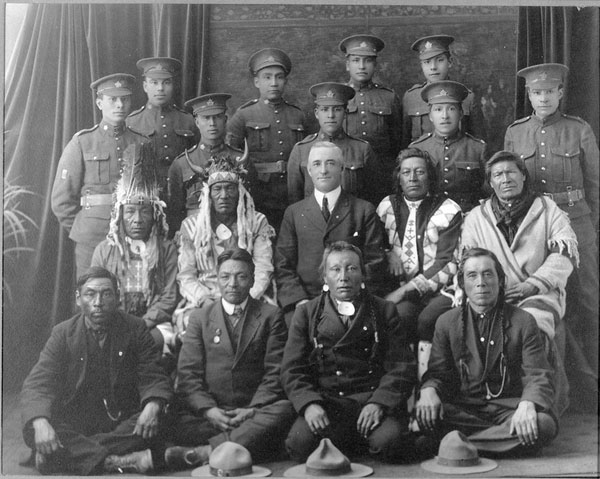

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3192219)

Indigenous soldiers and Elders from a Saskatchewan First Nations community during the First World War. The soldiers would become part of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), ca 1917.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo)

Private Tom Longboat buying a trench paper, June 1917.

Thomas Charles Longboat (4 June 1887 – 9 Jan 1949, Iroquois name: Cogwagee) was an Onondaga distance runner from the Six Nations Reserve near Brantford, Ontario and, for much of his career, the dominant long-distance runner. He was known as the “bulldog of Britannia” and was a soldier in the CEF during the First World War. Longboat served as a dispatch runner in France during the war. He was twice wounded and twice declared dead while serving in Belgium. He retired following the war.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3194489)

Cpl. Hughes, 4th Canadian Mounted Rifles. He was the first full blooded Indian to enlist in the CEF.

Chief Joe Dreaver, of Mistawasis Cree Band in Saskatchewan, served in both world wars. During the First World War, he was a sapper and earned the Military Medal, an award for bravery in the field, in Belgium. When war erupted again, he immediately re-enlisted, leaving his farm and bringing 17 men with him, including three of his sons. At 48, he was too old for overseas service and remained in Canada with the Veterans Guard, watching over prisoners of war in Alberta.

(Royal Canadian Legion, Happy Valley, Labrador Photo)

Lance-Corporal John Shiwak, a Labrador Inuit from Rigolet, served with the Royal Newfoundland Regiment.

He was killed on 20 Nov 1917 during fighting at Cambrai.

Frederick Freida was another Great War Inuit volunteer from the Labrador coast. During the Second World War, the presence of Inuit along the Labrador coast complicated the efforts of German U-boat crews in landing autotmated weather stations. Presently across the Canadian north, Inuit members of the Canadian Ranger Patrol Groups of the Canadian Forces reserve are an integral part of our militarypresence in the Arctic.

Henry Norwest, a Cree-Métis saddler, cowboy, trapper and hunter from Alberta, served as a sniper with the 50th Battalion C.E.F. Officially credited with 115 confirmed kills, the highest “score” recorded in the armies of the British Empire to that point, Norwest was killed in action on 18 Aug 1918 near Amiens.

(J. Moses Photo)

Charlotte Edith Anderson Monture, AEF, an Iroquois woman from the Six Nation’s of the Grand River reserve was living

and working as a registered nurse in New York City when the U.S. entered the First World War in 1917. Joining

the American Expeditionary Force as an army nurse, she served overseas in France until demobilized in 1919.

She returned home to the reserve to continue nursing, and to raise a family. Aboriginal women on the

homefront during both World Wars were heavily involved in charitable work, and with various forms of war

relief and soldier’s support. During the Second World War, a number of Aboriginal women served in the

women’s branches of the three services.

(Canadian Government Photo)

Francis Pegahmagabow MM and two bars (9 March 1891-5 Aug 1952).

This Ojibway war hero came from the Wasauksing First Nation. He was the most highly decorated First Nations soldier of the First World War. He was awarded the Military Medal three times, and seriously wounded during the war. He was an expert marksman and scout, credited with killing 378 Germans and capturing 300 more. Later in life, he served as chief and a councilor for the Wasauksing First Nation.

Following the outbreak of the First World War, Pegahmagabow volunteered for service with the CEF in August 1914. He was posted to the 23rd Canadian Regiment (Northern Pioneers). After joining the Canadian force he seerved at Camp Valcartier. While there he decorated his army tent with traditional symbols including a deer, the symbol of his clan. In February 1915 he was deployed overseas with the 1st Canadian Infantry Battalion of the 1st Canadian Division, which was sthe first contingent of Canadian troops sent to fight in Europe. His companions there nicknamed him “Peggy”.

Shortly after his arrival on the continent, Pegahmagabow fought in the Second Battle of Ypres, where the Germans used chlorine gas for the first time on the Western Front, and it was during this battle that he began to establish a reputation as a sniper and scout. Following the battle he was promoted to lance corporal. His battalion took part in the Battle of the Somme in 1916, during which he was wounded in the left leg. He recovered in time to return to the 1st Battalion as they moved to Belgium. He received the Military Medal for carrying messages along the lines during these two battles. Initially, his commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Frank Albert Creighton, had nominated him for the Distinguished Conduct Medal, citing his disregard for danger and “faithfulness to duty”, but it was downgraded.

On 6/7 Nov 1917, Pegahmagabow earned a Bar to his Military Medal for his actions in the Second Battle of passchendael. During the fighting, Pegahmagabow’s battalion was given the task of launching an attack at Passchendaele. By this time, he had been promoted to the rank of corporal and during the battle he was recorded playing an important role as a link between the units on the 1st Battalion’s flank. When the battalion’s reinforcements became lost, Pegahmagabow was instrumental in guiding them and ensuring that they reached their allocated spot in the line.

On August 30, 1918, during the Battle of the Scarpe, Pegahmagabow was involved in fighting off a German attack at Orix Trench near Upton Wood. His company was almost out of ammunition and in danger of being surrounded. Pegahmagabow braved heavy machine gun and rifle fire by going into no-man’s land and brought back enough ammunition to enable his post to carry on and assist in repulsing heavy enemy counter-attacks. For these efforts he received a second Bar to his Military Medal, becoming one of only 39 Canadians to receive this honour.

The war ended in November 1918 and in 1919 Pegahmagabow was invalided back to Canada . He had served for almost the whole war, and had built a reputation as a skilled marksman. Using the much-maligned Ross rifle, he was credited with killing 378 Germans and capturing 300 more. By the time of his discharge, he had attained the rank of sergeant-major and had been awarded the 1914-15 star, the British War Medal, and the Victory Medal. Upon his return to Canada he continued to serve in the Algonquin Regiment militia as a non-permanent active member. Following in his father’s and grandfather’s footsteps, he was elected chief of the Parry Island Band from February 1921. During the Second World War, Pegahmagabow worked as a guard at a munitions plant near Nobel, Ontario, and served as a Sergeant-major in the local militia. In 1943, he became the Supreme Chief of the Native Independent Government, an early First Nations organization. In 2003 the Pegahmagabow family donated his medals and chief head dress to the Canadian War Museum where they can be seen as of 2010 as part of the First World World War display.

(Government of Canada Photo)

Lieutenant Frederick Ogilvie Loft served with the Canadian Forestry Corps during the First World War. A Mohawk from the Six Nations of the Grand River, in 1919 he founded the League of Indians of Canada, the first national Native political organization in the country.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2095973)

Michel Ackbee, a sniper from the Thunder Bay Band, during the First World War.

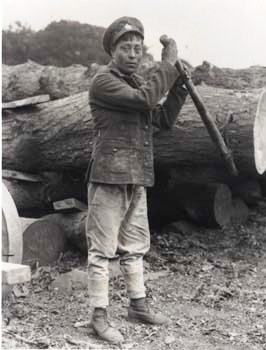

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, PA 5424)

First Nations soldier in the Canadian Forestry Corps during the First World War.

John McLeod, an Ojibwa, served overseas in the First World War and was a member of the Veterans Guard during the Second World War. Six of his sons and one of his daughters enlisted. Two sons gave their lives, and another two were wounded. In 1972, John’s wife, Mary, became the first Indigenous woman to be named Canada’s Memorial Cross Mother, placing a wreath at the National War Memorial in Ottawa on Remembrance Day on behalf of all Canadian mothers who had lost children to the war. The Canadian Forces named the 3rd Canadian Ranger Patrol Group HQ Building at CFB Borden, Ontario, in his honour.

(J. Moses Photo)

Subalterns of “A” Company, 107th “Timberwolf” Battalion, France, 29 July 1917. Sitting in the front row, left is Lieutenant Oliver Martin, a Mohawk from the Grand River Reserve; and back row standing at right, Lieutenant James Moses, a Delaware from the same Reserve. Both were later seconded to the Royal Flying Corp s. Martin survived the war as a pilot, stayed active in the Canadian Militia during the interwar years, and was appointed Brigadier during the Second World War. Moses was reported missing, later confirmed killed, on 1 April 1918 while serving as an air observer. A third First Nations junior officer from the 107th, John Randolph Stacey, a Mohawk from Kahnawake, also became a pilot, but was killed in a flying accident in England a week after Moses.

Brigadier Oliver Milton Martin, a Mohawk from the Six Nations Grand River Reserve, reached the highest military rank ever held by an Indigenous person. During the First World War, he served in both the army and the air force. During the Second World War, he oversaw the training of hundreds of recruits in Canada. For his 20 years of excellent service, he was awarded the Colonial Auxiliary Forces Officer’s Decoration.

More than 6,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis served with British forces during the First World War and the Second World War. A generation of young native men fought on the battlefields of Europe during the Great War and approximately 300 of them died there. When Canada declared war on Germany on 10 Sep 1939, the native community quickly responded to volunteer. Four years later, in May 1943, the government declared that, as British subjects, all able Indian men of military age could be called up for training and service in Canada or overseas.

Second World War

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3203934)

Members of The Cape Breton Highlanders baseball team at the Snow Haven rest camp, Fornelli, Italy, 2 May 1944. Winslow Eagle child noted that his First Nations father top center, Pat Eagle Child, is a Blackfoot from The Blood Tribe, Kainai Nation, Southern Alberta.

(DND Photo)

Sergeant Tommy Prince (R), M.M., 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, PA-142289)

Sergeant Tommy Prince (R), M.M., 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, with his brother, Private Morris Prince, at an investiture at Buckingham Palace, 12 Feb 1945.

Pte Tommy Prince in the Second World War. An Ojibwa from Manitoba, he volunteered to be a paratrooper. He served with the elite Canadian-American commando unit called the First Special Service Force that became known to the Germans as the Devil’s Brigade. He earned the Military Medal during a battle in Italy, and the Silver Star, an American award for gallantry, for his reconnaissance work in France. These awards were presented to him by King George VI at Buckingham Palace.

Charles Byce, the son of a Cree woman, joined the Lake Superior Regiment (Motor). He won the Military Medal in the Netherlands and the Distinguished Conduct Medal in the Rhineland Campaign. His citation for the latter was impressive: “His gallant stand, without adequate weapons and with a bare handful of men against hopeless odds will remain, for all time, an outstanding example to all ranks of the Regiment.”

(DND Photo)

David Greyeyes, a member of the Muskeg Lake Cree Band in Saskatchewan, enlisted in 1940 and attained the rank of Sergeant overseas before being returned to Canada in February 1943 for officer training. Returning to Britain as a Lieutenant in July 1943 “he was believed to be the only officer of Indian blood who is serving in the Canadian Army overseas”. He served in seven European countries in many difficult military roles, including commanding a mortar platoon in Italy. During the Italian Campaign, he earned the Greek Military Cross (third class) for valour in supporting the Greek Mountain Brigade. In 1977 he was awarded the Order of Canada. His citation reads: “Athlete, soldier, farmer, former Chief of the Muskeg Lake Reserve, Saskatchewan, and ultimately Director of Indian Affairs in the Maritime and Alberta Regions. For long and devoted service to his people, often under difficult circumstances.”

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, 29 September 1942. PA-129070)

Mary Greyeyes, a member of the Canadian Women’s Army Corps, during the Second World War. Councillor Harry Bull, of the Piagut Indian community near Regina who lost a leg at Vimy Ridge in the Great War is shown giving his blessing.

Mary Greyeyes Reid, Cree veteran of the Second World War (born 14 November 1920 on the Muskeg Lake Cree Nation reserve, Marcelin, Saskatchewan; died 31 March 2011 in Vancouver, BC). Mary was the first Indigenous woman to join Canada’s armed forces, becoming a member of the Canadian Women’s Army Corps during the Second World War. She served in the CWAC as a cook and was posted overseas to England in a Laundry Unit. In an effort to boost Indigenous recruitment in the Canadian forces, she posed for this photo that was widely circulated in Canada.

When the Second World War erupted in September 1939, many Indigenous people again answered the call of duty and joined the military. By March 1940, more than 100 of them had volunteered and by the end of the conflict in 1945, over 3,000 First Nations members, as well as an unknown number of Métis, Inuit and other Indigenous recruits, had served in uniform. While some did see action with the Royal Canadian Navy and Royal Canadian Air Force, most would serve in the Canadian Army.

While Indigenous soldiers again served as snipers and scouts, as they had during the First World War, they also took on interesting new roles during this conflict. One unique example was being a “code talker.” Men like Charles Checker Tompkins of Alberta translated sensitive radio messages into Cree so they could not be understood if they were intercepted by the enemy. Another Cree-speaking “code talker” would then translate the received messages back into English so they could be understood by the intended recipients.

The Mi’kmaq on Prince Edward Island had a greater percentage of soldiers serving in both World Wars compared with other communities. A Mi’kmaq soldier named Lawrence Maloney, who was born in Nova Scotia but moved to Lennox Island, PEI after the end of the Second World War saw service in Poland. He was captured by the Nazis and taken to a concentration camp where he was subjected to mistreatment and forced labour. Many years after the war, Maloney, who was a residential school survivor, described life in the concentration camp as harsh but added the residential schools were sometimes harder.

Indigenous service members would receive numerous decorations for bravery during the war. Willard Bolduc, an Ojibwa airman from Ontario, earned the Distinguished Flying Cross for his brave actions as an air gunner during bombing raids over occupied Europe. Huron Brant, a Mohawk from Ontario, earned the Military Medal for his courage while fighting in Sicily.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3193153)

Huron Brant receiving his Military Medal from Lieutenant-General Sir Bernard Montgomery at Catanzo, Italy in 1943.

The Korean War erupted in the Far East in 1950 and several hundred Indigenous people would serve Canada in uniform during the conflict. Many of them had seen action in the Second World War which had only come to an end five years earlier. This return to service in Korea would see some of these brave individuals expanding on their previous duties in new ways.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, PA-128264)

Tommy Prince, PPCLI, during the Korean War.

(PPCLI Museum and Archives in Calgary )

Sgt. Tommy Prince (centre), from Brokenhead Ojibway Nation, in Korea.

Tommy Prince, an Ojibwa from Manitoba, served with the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry in Korea. He would draw upon his extensive infantry experience in the Second World War with missions like a “snatch patrol” raid. Prince was second-in-command of a rifle platoon and led a group of men into an enemy camp where they captured two machine guns. He also took part in the bitter Battle of Kapyong in April 1951 which saw his battalion subsequently awarded the United States Presidential Unit Citation for its distinguished service, a rare honour for a non-American force. His cunning and bravery earned him a dozen medals, including battle honours for service in Korea with the PPCLI.

Indigenous men and women have continued to proudly serve in uniform in the post-war years, as well. Like so many of those who have pursued a life in the military, they have been deployed wherever they have been needed—from NATO duties in Europe during the Cold War to service with United Nations and other multinational peace support operations in dozens of countries around the world. In more recent years, many Indigenous Canadian Armed Forces members saw hazardous duty in Afghanistan during our country’s 2001-2014 military efforts in that war-torn land.

(Department of National Defence Photo, IS2012-1012-06)

A Canadian Ranger during a patrol in Nunavut in 2012.

Canadian Rangers crest.

Closer to home, Indigenous military personnel have filled a wide variety of roles, including serving with the Canadian Rangers. This group of army reservists is active predominantly in the North, as well as on remote stretches of our east and west coasts. The Rangers use their intimate knowledge of the land there to help maintain a national military presence in these difficult-to-reach areas, monitoring the coastlines and assisting in local rescue operations.

The story of Indigenous service in the First and Second World Wars, the Korean War and later Canadian Armed Forces efforts is a proud one. While exact numbers are elusive, it has been estimated that as many as 12,000 First Nations, Métis and Inuit people served in the great conflicts of the 20th century, with at least 500 of them sadly losing their lives.

This rich heritage has been recognized in many ways. The names given to several Royal Canadian Navy warships over the years, like HMCS Iroquois, Cayuga and Huron, are just one indication of our country’s lasting respect for the contributions of Indigenous peoples. This long tradition of military service is also commemorated with the striking National Aboriginal Veterans Monument in Ottawa. This deeply symbolic memorial features a large bronze eagle at its top, with four men and women from different Indigenous groups from across Canada immediately below. A wolf, bear, bison and caribou, powerful animals that represent “spiritual guides” which have long been seen by Indigenous cultures as important to military success, look out from each corner. Remembrance ceremonies are held at this special monument, including on National Aboriginal Veterans Day which is observed each year on 8 November.

(I, Padraic Ryan Photo)

Following the end of the Second World War, laws concerning First Nations in Canada began to change, albeit slowly. The federal prohibition of potlatch and Sun Dance ceremonies ended in 1951. Provincial governments began to accept the right of Indigenous people to vote. In June 1956, section 9 of the Citizenship was amended to grant formal citizenship to Status Indians and Inuit, retroactively as of January 1947. In 1960, First Nations people received the right to vote in federal elections without forfeiting their Indian status. After the Canadian Supreme Court recognized that indigenous rights and treaty rights were not extinguished, a process was begun to resolve land claims and treaty rights and is ongoing today.

Today, more than 1200 First Nations, Inuit and Métis Canadians serve with the Canadian Forces at home and overseas with the same fervour and pride as their ancestors. Their diversity is extraordinary. They represent over 640 distinct bands, sharing common beliefs and practices, and all unique in themselves. As well, there are 55 languages and distinct dialects that belong to 11 linguistic families.

(Sources: Veterans Affairs Canada)

Aboriginal Awareness Group, Capt Petra Comeau, Shannon Johnson, Maj Hal Skaarup, Sgt CW Paul (St. Mary’s First Nation), Lt Gov Nicholas Graydon (former Captain in the Canadian Forces, Tobique First Nation) induction day, Fredericton 2009.

(DND Photo)

Sgt CW Paul (St. Mary’s First Nation), attending a pow-wow in Toronto, 2009.

(DND Photo)

Aboriginal Awareness Day, Author briefing members of 3 ASG (now 5 CDSB) Gagetown, attending the sunrise ceremony at the site of the original St. Mary’s Reserved on the Saint John River, 14 May 2009.

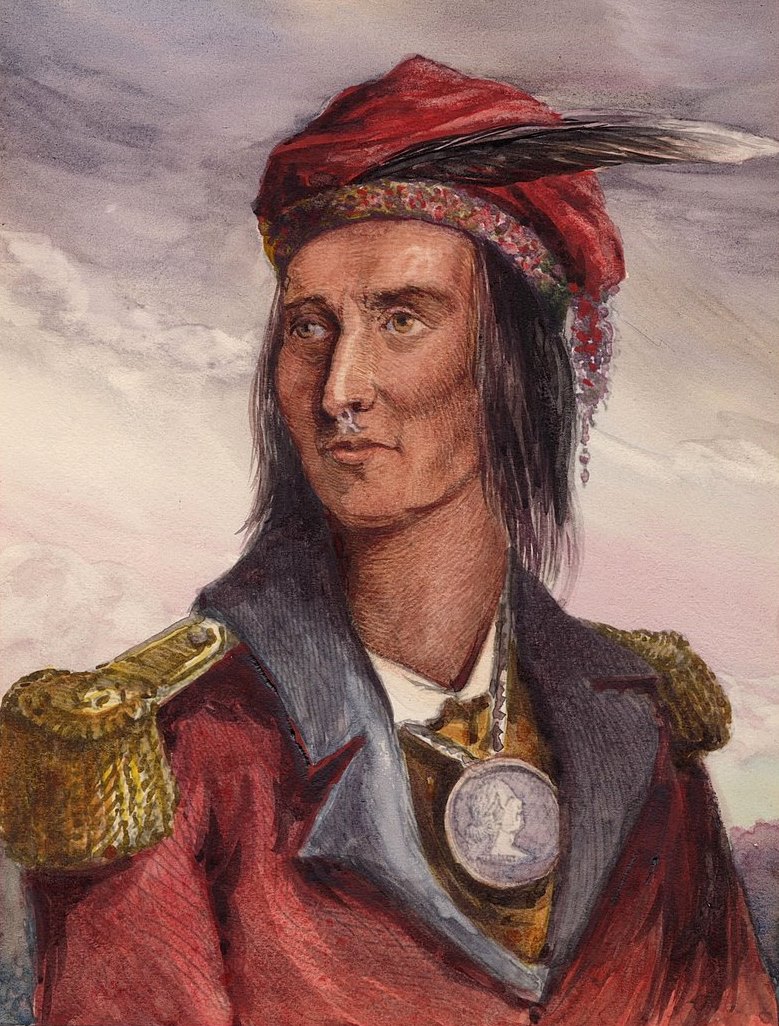

Chief Tecumseh – when your time comes.

“So live your life that the fear of death can never enter your heart. Trouble no one about their religion; respect others in their view and demand that they respect yours. Love your life, perfect your life, beautify all things in your life. Seek to make your life long and its purpose in the service of your people. Prepare a noble death song for the day when you go over the great divide.”

“Always give a word or a sign of salute when meeting or passing a friend, even a stranger, when in a lonely place. Show respect to all people and grovel to none.”

“When you arise in the morning give thanks for the food and for the joy of living. If you see no reason for giving thanks, the fault lies only in yourself. Abuse no one and no thing, for abuse turns the wise ones to fools and robs the spirit of its vision.”

“When it comes your time to die, be not like those whose hearts are filled with the fear of death, so that when their time comes they weep and pray for a little more time to live their lives over again in a different way. Sing your death song and die like a hero going home.”

Chief Tecumseh. A portrait reproduced by Nenson John Lossing from a pencil sketch by French trader Pierre Le Dru at Vincennes, taken from life about 1808.

(Photo by Dennis Jarvis, published in the Star Weekly, 4 Sep 1971)

Chief Margaret Pictou LaBillois of the Eel River Bar First Nation near Dalhousie, New Brunswick.

Chief LaBillois was the first of her Eel River Bar First Nation community to graduate high school in 1939. After graduating from high school, she joined the RCAF, and served an Aircraftwoman First Class. She was a photo-reconnaissance technician who worked on mapping the Alaska Highway, which was constructed during the Second World War to connect Alaska to Canada and the rest of the United States.

In 1982, she graduated from Lakehead University with an Honours Degree in Native Languages. In 1970, she was elected as Chief of Eel River Bar First nations, making her the first female chief in New Brunswick. Chief LaBillois received the Order of Canada in 1996 in recognition of her leadership abilities, and the Order of New Brunswick in 2005 for her protection of Mi’kmaq language. She “walked” on 19 April 2013 at the age of 89.