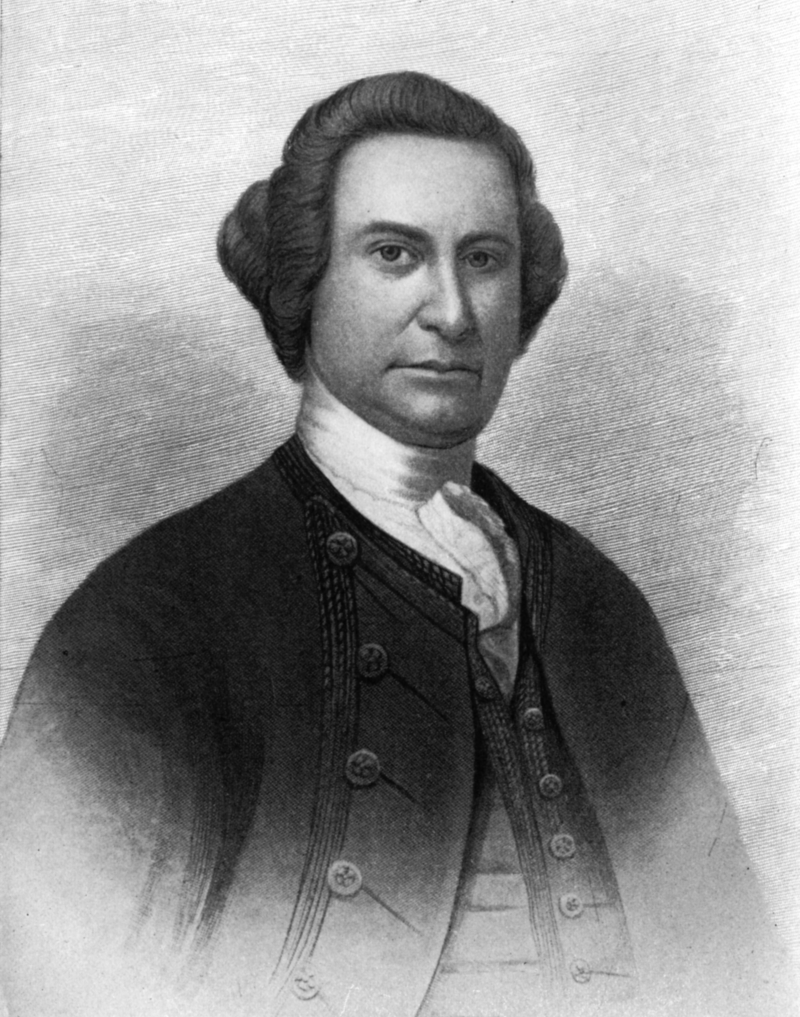

Elijah Estabrooks (1727-1796)

Elijah Estabrook’s served as a Massachusetts provincial soldier in the French and Indian War (1754-1763). He kept a journal between 1758 and 1760 covering his military service. One of my ancestors, he was also one of the earliest settlers on the Saint John River, and now lies buried near Jemseg, New Brunswick. This is a compilation of his stories with additional details and illustrations of the people and events he wrote about in his Journal, as a tribute from one of his many descendants. Part 1.

The French and Indian War

The French and Indian War is also known as the Seven Years War. It began on the 17th of April 1754, and concluded with the Treaty of Paris on the 10th of February 1763. With the signing of this treaty, Canada was ceded to Britain. One of the major battles in the North American campaign of this war was fought at Fort Carillon, also known as Ticonderoga. This is the story of Elijah Estabrooks, one of the Massachusetts Provincial soldiers who took part in that battle.

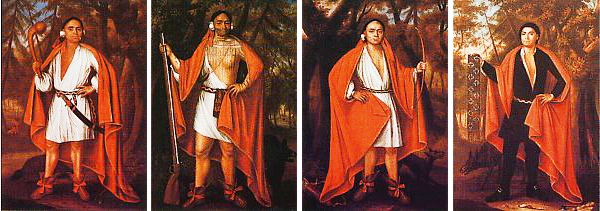

Elijah and his fellow Massachusetts Provincial soldiers may have looked like this in uniform. Terry Hawkins, another descendant of Elijah, is the model, and he is part of a group of re-enactors who have recreated Israel Harrack’s Company of Colonel Jedediah Prebles’ Regiment of Massachusetts Provincials in Shelburne, Nova Scotia. The group travels frequently to French and Indian War re-enactment encampments in the US and Canada, including Fort Ticonderoga and Fortress Louisbourg.

Foreword

The Journal of Elijah Estabrooks covers about three years of a particularly important period in the history of North America. The conflict in which he participated shaped the future of the whole area for many years to come. Had that war not terminated as it did, the movement of great numbers of efficient settlers, including Elijah Estabrooks, from New England to what was then Nova Scotia would not have taken place in the years immediately following 1759.

On the 11th of January 1759, a proclamation was made by Charles Lawrence, Governor of Nova Scotia, offering grants of land and free liberty of conscience to Protestants dissenting from the Church of England. This proclamation was printed by John Draper at Boston in the same year. The defeat of the French forces led to the release of some women and children who had been captured by Indians in Nova Scotia and taken to Quebec, and made it safe for farmers and fishermen to settle over most of the Province.

When Elijah Estabrooks marched to Cornwallis in June 1760, he would have seen one building which is still standing, namely the blockhouse of Fort Edward in present-day Windsor. About 50 years ago the old shingles were being replaced on the sides of this building. I was visiting relatives in the town at the time and went to see the blockhouse when the huge pine timbers were bare. There were many musket balls embedded about two inches deep in the timbers, mostly near the door and the loopholes.

Elijah Estabrooks would have seen the newly arrived settlers at work on their farms and buildings as he passed through the Townships of Newport, Falmouth, Horton and Cornwallis, which were all settled by New England planters in that year. The soldiers seem to have been sent to Cornwallis to protect the newly arrived settlers from Indian raids, which did not take place. While at that township they would have seen the fruit trees and rich soil as well as the many acres of diked land; exceptionally good land free of rocks, providing pasture and hay for cattle and sheep. The lifestyle in these settlements would have been more compatible to anyone with puritan values than in the city of Halifax of that day.

Farmland in the long-settled towns near the coast in New England was nearly all occupied and expensive, while the lands in Nova Scotia were free. Many who emigrated in response to Lawrence’s proclamation were of Separate Congregationalist, Quaker, and Baptist faith, or leaned toward these groups. They had suffered religious restriction in Connecticut and parts of Massachusetts, including being taxed to pay the salaries of ministers they disapproved of. Governor Lawrence’s proclamation stated this would not occur in Nova Scotia.

Elijah Estabrooks brought his family to Cornwallis where the level land must have reminded him of the interval land on the Saint John River, that had some advantages over the land on the Minas Basin. Both places were subject to flooding at times, but the river water did no harm to the soil, whereas when the sea broke through the dikes, it was said to take three years for the salt to leach out of the soil, so that grass would grow again. Both places were accessible to small vessels of that day. The shores at Cornwallis had extremely high tides and were lined with either high cliffs or very wide mud flats, whereas small vessels could come almost to the doors of the settlers on the Saint John River. No less than seventeen families beside Elijah Estabrooks removed from Cornwallis and vicinity to the Saint John River before the Revolutionary War.

Journals exist of other soldiers who traveled the road to Windsor about the same period as Elijah Estabrooks, but they did not return to the area as he did. Here, he gained considerable influence among the many planters on the Saint John River and religious meetings were regularly held at his house for many years. At least in his later years he was affiliated with what were then called “Newlight Congregationalists” who built a meetinghouse which some called “Brooksite” because the Estabrooks men were leaders in building it. When the congregation with their preacher Elijah Estabrooks Junior formed a Baptist Church in 1800, they “inherited the meetinghouse.”

Major Harold Skaarup has done a fine job, explaining the various campaigns in which Elijah Estabrooks participated and other events of the French and Indian, or Seven Years War. Not only will the descendants of Estabrooks find this book of great interest, but the public in general will find it fascinating reading if they are interested in history. The events described are fact not fiction.

I consider it an honour to have been asked to write this Foreword.

Frederick C. Burnett

26 October 2000

Preface

On the 8th of February 1997 the Queen’s County Historical Society in Jemseg, New Brunswick, invited me to give a presentation on an ancestor of mine named Elijah Estabrooks (1727-1796). The subject was Elijah’s Military Service as a Colonial soldier during the period from 1758 to 1760, just prior to his settlement on the Saint John River. The meetinghouse where I spoke to the members of the society stood less than a kilometer from where Elijah lay buried. His remains lie within eyesight of the new Trans-Canada Highway bridge over the river at Jemseg, in what is known locally as the Old Garrison Graveyard, one of the oldest in that part of New Brunswick.

One may find as many as 25 or 30 gravesites on this former farmland that was once the property of a pre-Loyalist family named Garrison. It later went to the family of Jefferson Dykeman and is presently on the property of John Gardner. The gravesite is in fact, now a cattle pasture with a very impressive (and incredibly old) Burr Oak tree standing watch over it. The grass has grown long because of the frequent flooding over the site by the Saint John River each spring, as of the spring of 2001. John’s hand painted marker, however, is still readily visible on the site which lies across from house number 12 on the river road. The first time I saw the site, I couldn’t help thinking that many of the early settlers on the Saint John River that are interred here like Elijah, must have had interesting histories worth further research. For those of you who are, like me, descended from these same settlers, that research may prove as rewarding as mine did, and you may well find that you have the grist for a similar history about your ancestors. Good hunting to you.

This book is about one of these colonists, some of whom were the earliest settlers in the Queen’s County area, back when the territory was still part of the province of Nova Scotia. At least two family members of the original contingent of Loyalists who came to this part of New Brunswick are also buried there, including George Ferris, the forebear of the Queen’s County Ferris’s, as well as a number of Pre-Loyalists like Elijah Estabrooks along with his first wife Mary and his second wife Sarah. Other family names, which would have been familiar to many of those who gathered to hear the presentation, are buried on nearby farms from the same era. Their names include the Purdeys, Starkeys, Dykemans, Gilberts, Colwells, Hatfields, Hanselpackers, Springers, Currys, Mullens, Camps, Gunters, Carpenters and Thurstons.

Later on, there were Oakleys, Nevers, Huestis, Gidneys, Porters and Bates families. The majority of these early settlers were Loyalists except for the Garrisons, Estabrooks and Nevers, who were pre-Loyalists from Massachusetts. The Gunters were from Hanover, Germany, the Dykemans were Old New York State Dutch, and the Springers were Swedish.

As I have mentioned, each settler would have had an interesting story to tell. The particular story I intend to expand on in this book is the military record of a family ancestor of mine named Elijah Estabrooks. Elijah kept a Journal during his travels and recorded his experiences from the time he grew up in New England and throughout the period when he fought in the Seven Years War as a Massachusetts Provincial soldier. This war ended in 1763 with the defeat of the French forces in North America, and with the major result being that Canada was ceded to Britain. Elijah survived his battle experiences, and shortly after his discharge in 1760, he emigrated to this part of the Maritimes which was then known as Nova Scotia. A brief summary of what happened to Elijah during this period follows.

Introduction

As a soldier in the Massachusetts Provincials, Elijah Estabrooks participated in the battle that took place against Montcalm’s French forces at Fort Ticonderoga on the 8th of July 1758. Elijah kept a daily journal of the events that unfolded as he saw them, and later, when he became one of the earliest settlers on the Saint John River in what is now the province of New Brunswick, his journal was passed on to his descendants. Elijah described the events of the battle as he saw them from an “up close and very personal” point of view. The following is one example:

We marched within 30 or 40 rods of the French trenches and set the battle in array. And we had about as smart a fight for about 4 hours as ever was heard or seen in England, Flanders, or America. And the French prevailed very much…but it was through deceit…for they acted contrary to the acts of all kings and parliaments…for in the midst of their fight they hoisted an English flag in heir trench only to deceive us, and so it did, for we thought that they had given up. And drew up and was going to take possession – when all at once they hauled that down and hoisted their own, and with a great hellish shout poured a volley upon us, and killed more at that time than they had before – 2,541 of our men they killed and wounded 1,473.[1]

The battle clearly left an indelible impression on Elijah and as indicated; his journal makes remarkably interesting reading. It opens a window onto one man’s view of the French and Indian War in New England, and his subsequent service in the British forces in Halifax during events that would eventually lead to the ceding of Canada to Britain. In many ways, the observations that he made in his journal are a written heirloom that has been passed on and shared among his many New Brunswick descendants and other interested readers.

Elijah Estabrooks was the son of Elijah and Hannah (Daniel) Estabrooks, and he was born in 1727 or 1728. Some of his family had originally immigrated to Boston from Enfield, England in 1660, settling nearby in Boxford, Massachusetts. His journal provides a rich treasure trove of eyewitness detail covering the English campaign in 1758 against the French and Indian forces as they unfolded during an interesting period of the Seven Years War. His journal is also a personal record of his experiences in the Massachusetts Provincial Army during the years 1758-1760.[2] Elijah was a volunteer soldier in a Company commanded by Captain Israel Herrick, an officer under the command of Colonel Jedediah Preble and his Regiment of Massachusetts Provincial soldiers.[3]

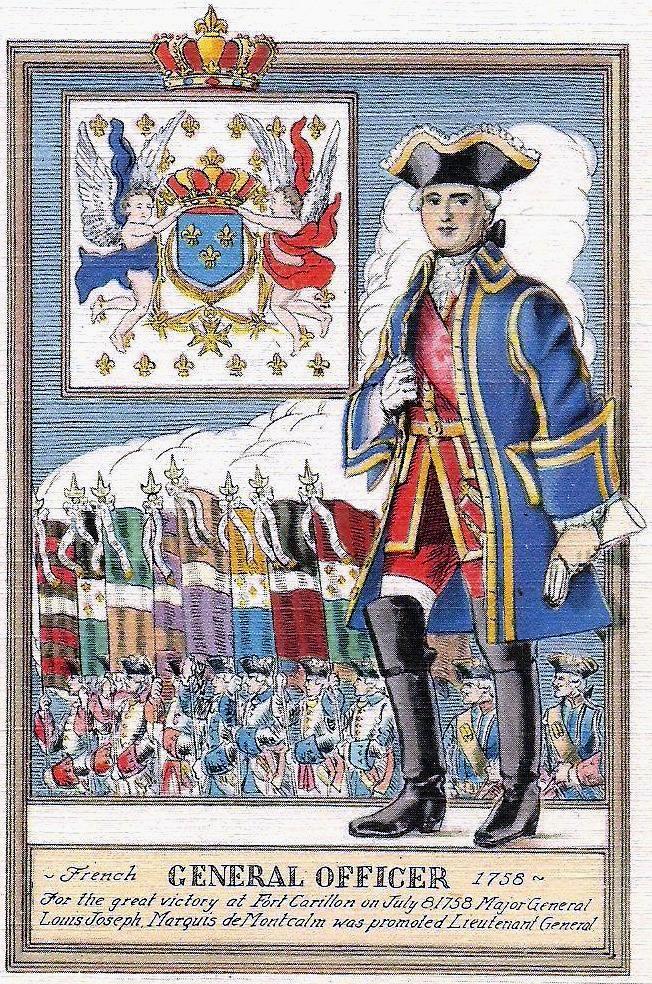

Elijah’s record is a very personal account of the heavy casualties and the defeat that the British forces suffered shortly after the death of Brigadier (and Lord) George Augustus Howe. Howe had been a highly competent commander and one of British Prime Minister Pitt’s “chosen” young men. Unfortunately, he was killed in a skirmish that took place just before the battle at Ticonderoga, and tactical command of the assaulting force was assumed by a British General named Abercrombie. Abercrombie chose to conduct a frontal assault against well dug in troops without using any of his readily available artillery.[4] The result was a bloodbath for the British forces. General Louis-Joseph Marquis de Montcalm and his French forces conducted a spirited and successful defence, although the victory was due more to Abercrombie’s poor assessment of the French defences than to the best choice of ground, position, and tactics.

[1] Journal of Elijah Estabrooks, Haverhill, Massachusetts, 1758-1760, p. 7.

[2] A photo of what Elijah and his fellow Massachusetts Provincial soldiers may have looked like in uniform is re-produced on the cover and throughout this book. Terry Hawkins, another descendant of Elijah, is the model, and he is part of a group of re-enactors who have recreated Isreal Harrack’s Company of Colonel Jedediah Preble’s’ Regiment of Massachusetts Provincials in Shelburne, Nova Scotia, Canada. The group travels frequently to French and Indian War re-enactment encampments in the US and Canada, including Fort Ticonderoga and Fortress Louisbourg. For anyone interested, they can be contacted by mail at the following address: PO Box 999, Shelburne, Nova Scotia, Canada, BOT 1WO, or by email: shoover@aei.ca.

[3] General Jedidiah Preble was born in Wells, Maine in 1707 and began life as a sailor. In 1746 he became a Captain in a provincial regiment. He became a very prominent resident of Portland who settled on The Neck about 1748. In 1755 he held a command as a Lieutenant-Colonel under General John Winslow and assisted in removing the Acadians from Canada. He became a Colonel on 13 March 1758. On 17 March 1759 he was promoted to the rank of Brigadier-General. He was in charge of a company that served under General Wolfe and he was in the battle on the Plains of Abraham standing near General Wolfe when Wolfe was killed. Preble, who was wounded twice during the war was in command of a garrison at Fort Pownal at Fort Pownal on the Penobscot River when peace finally came in 1763. In 1775, General Preble, then 68, was appointed to the rank of Major General and was asked to serve as commander-in-chief of the Massachusetts forces, but he declined citing the infirmities of age. He served 12 years as Portland’s representative to the legislature, was chosen the first senator from Cumberland County under the constitution of 1780, and was a judge of Common Pleas from 1782-83. He died in Portland, Maine on 16 March 1784, at age 77. He had four sons and one daughter by his first wife, Martha (Junkins), of York, and five sons by his second wife, the widow of John Roberts and daughter of Joshua Bangs of Portland. Internet: http://portlandmainehistory.wordpress.com/tag/general-jedidiah-preble/; and http://famousamericans.net/jedediahpreble/.

[4] According to Francis Parkman, Brigadier Lord Howe was one of the most beloved British officers who ever led provincial troops in America. Massachusetts-Bay put up a monument to him in Westminster Abbey, where it may still be seen. He was a younger brother to Admiral Lord Howe and General William “Billy” Howe of the War of Independence. William had been with Amherst at Louisbourg. Francis Parkman, Montcalm and Wolfe, Viking, Markham, Ontario, 1984, p. 441.

According to Robert Leckie, Augustus Howe was an excellent soldier. He was also one of the few British commanders who respected the colonists. He had served with the Rangers led by (then) Captain Robert Rogers, and he insisted that the 6,350 regulars as well as the 9,000 colonials whom Abercrombie was to lead against Ticonderoga, learn to live and fight as the Rangers did. Robert Leckie, The Wars of America, Vol I, Harper Collins Publishers, New York, NY, 1992, p. 57.

Lord and Brigadier George Augustus Howe (age 34). It has been reported that George Howe was as capable and as popular a soldier as then served the king in 1758. He was killed in a French ambush near Lake George on the 5th of July 1758, as he advanced at the head of General Abercrombie’s 15,000-man army just prior to the assault on Fort Ticonderoga.

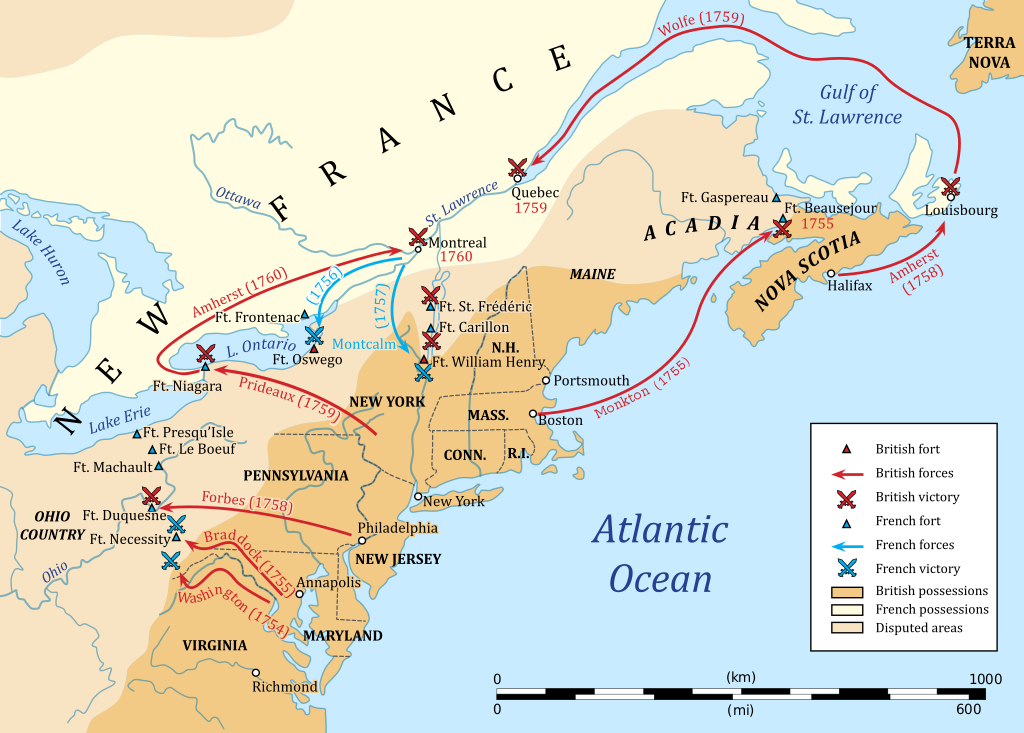

Maps of the French and Indian War

(Hoodinski Map)

Schematic map of the French and Indian War.

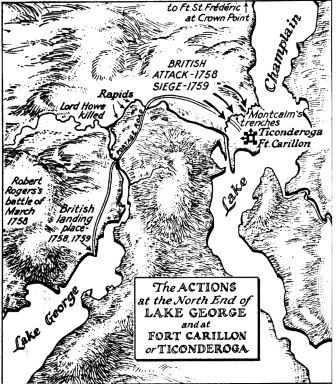

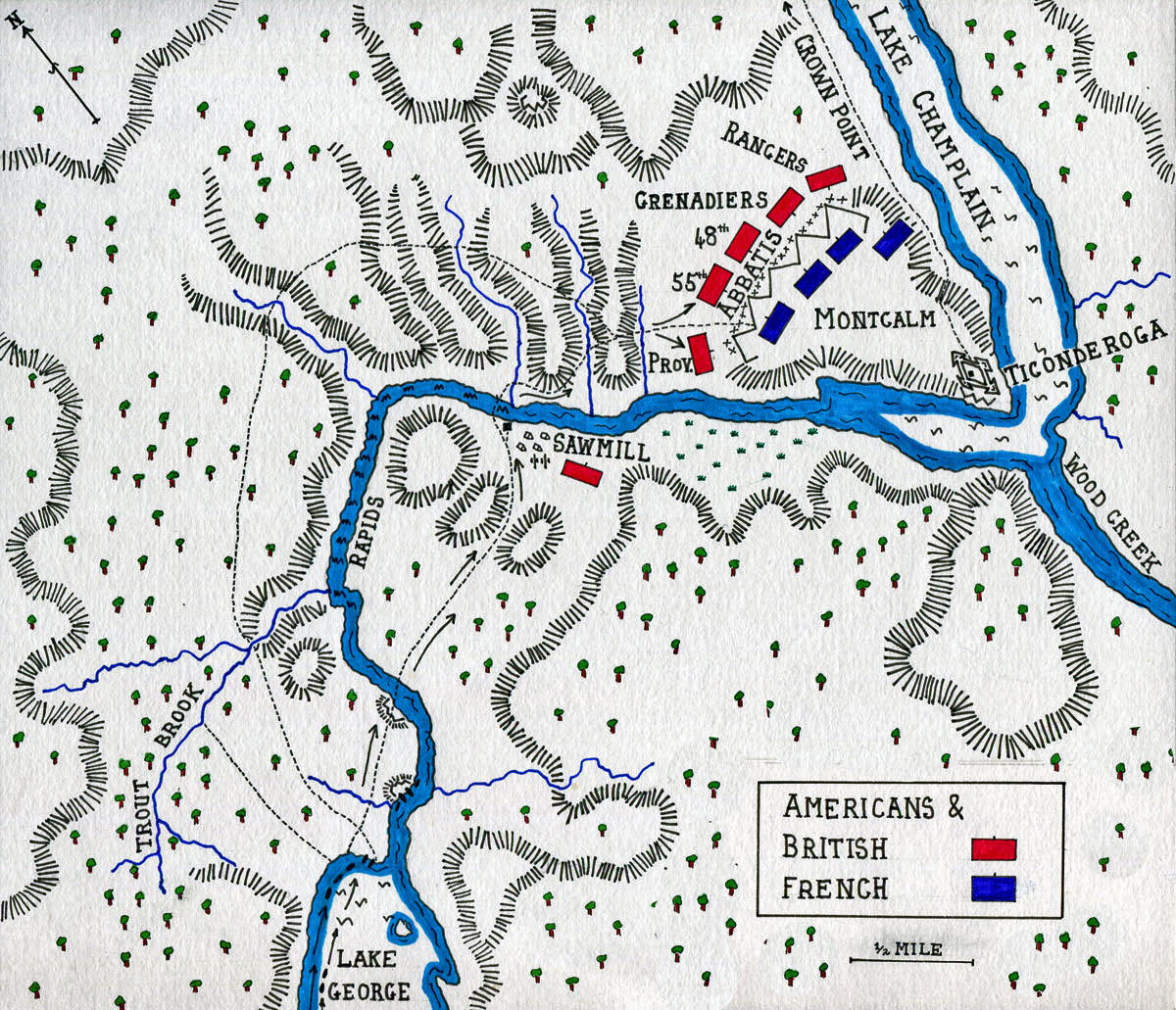

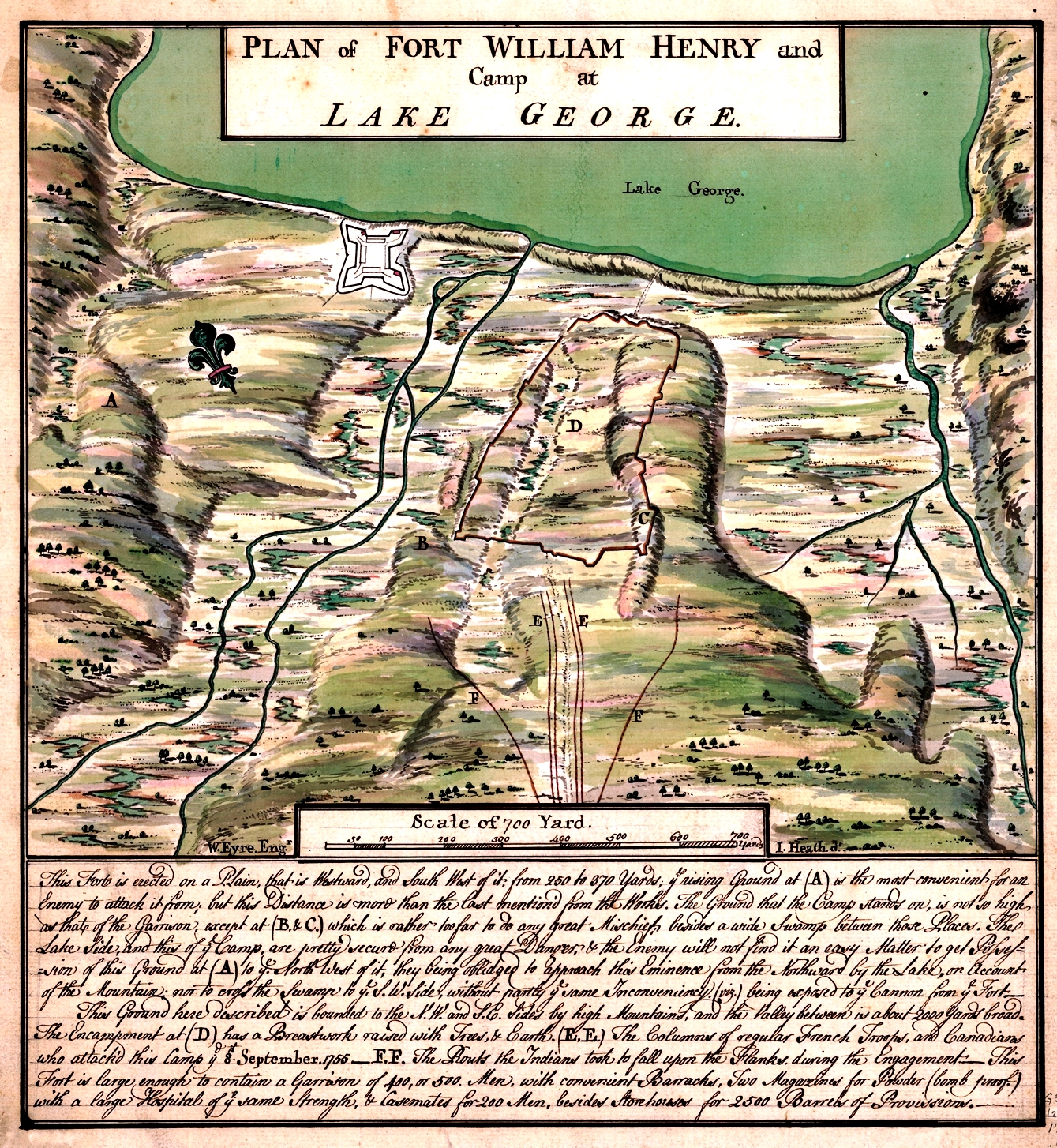

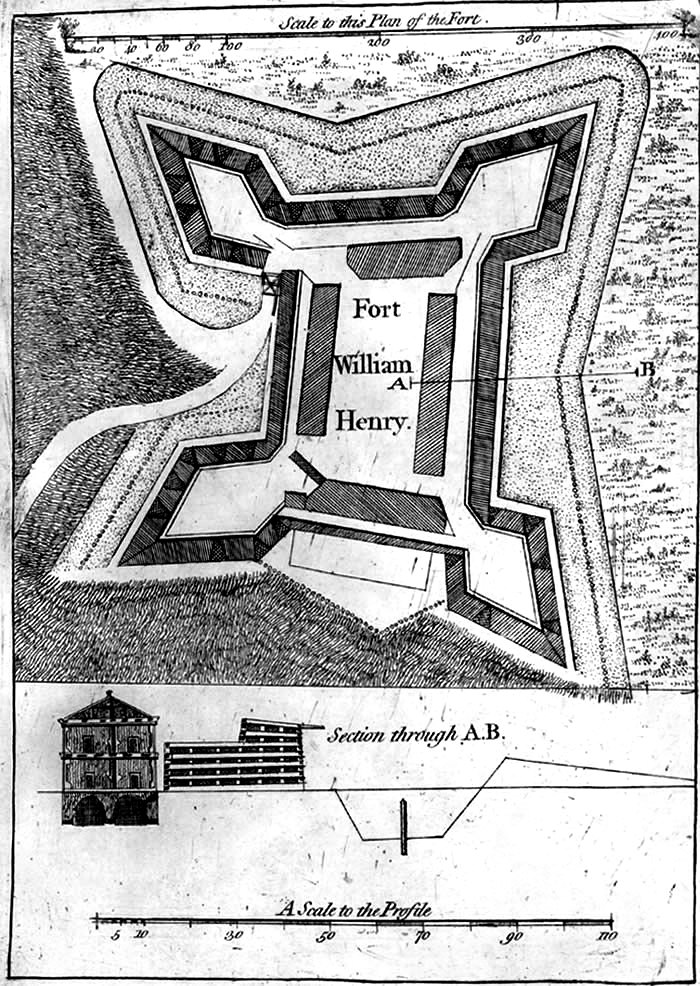

Map of Actions described in Ticonderoga Soldier. This map outlines the military activities that took place at the North end of Lake George in July 1758, indicating where Lord Howe was killed and where Montcalm laid out his defensive position before Fort Carillon – Fort Ticonderoga.

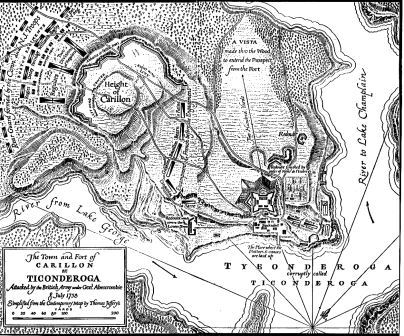

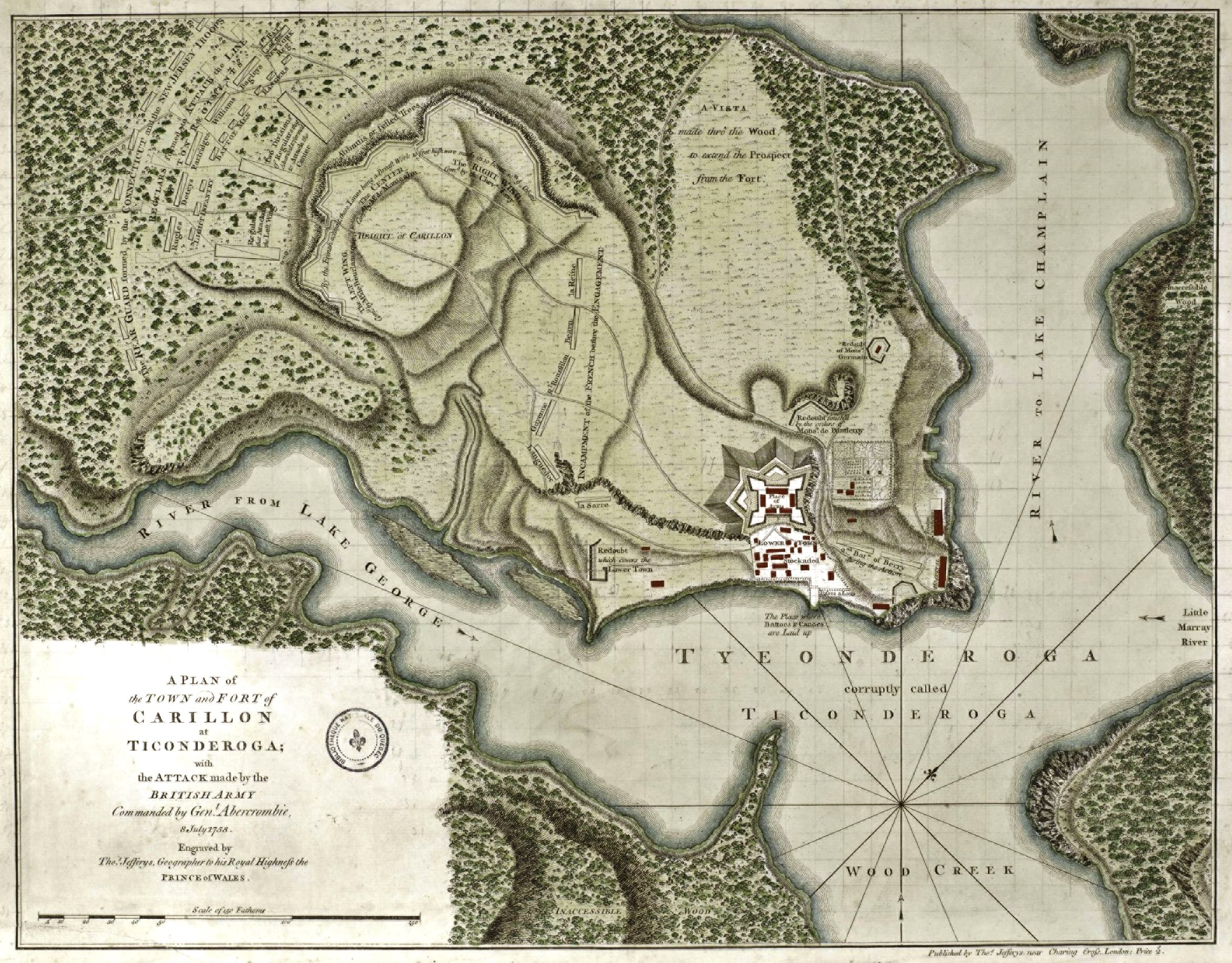

Map of the town and Fort of Carillon at Ticonderoga. This map shows the dispositions of the French forces under Montcalm deployed to the West of the fort, and the attacking British forces under General Abercrombie North West of the height of Carillon, as they were assembled on the 8th of July 1758. (Simplified from a contemporary map by Thomas Jeffreys). (Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4162110)

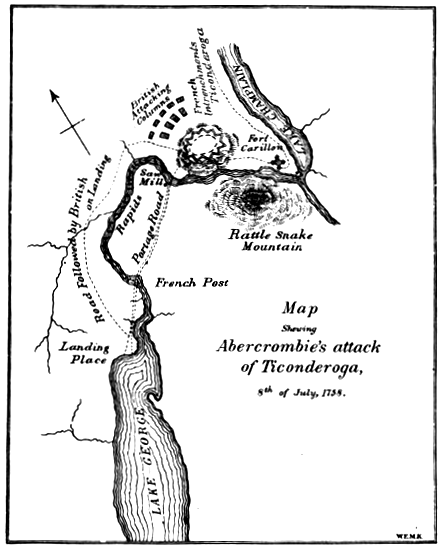

Map showing the movement of General James Abercrombie’s army as it approached Fort Carillon in 1758. William Kingsford.

Map showing Fort Ticonderoga (then known as Fort Carillon) in 1758. (Thomas Jefferys, Library and Archives of Quebec)

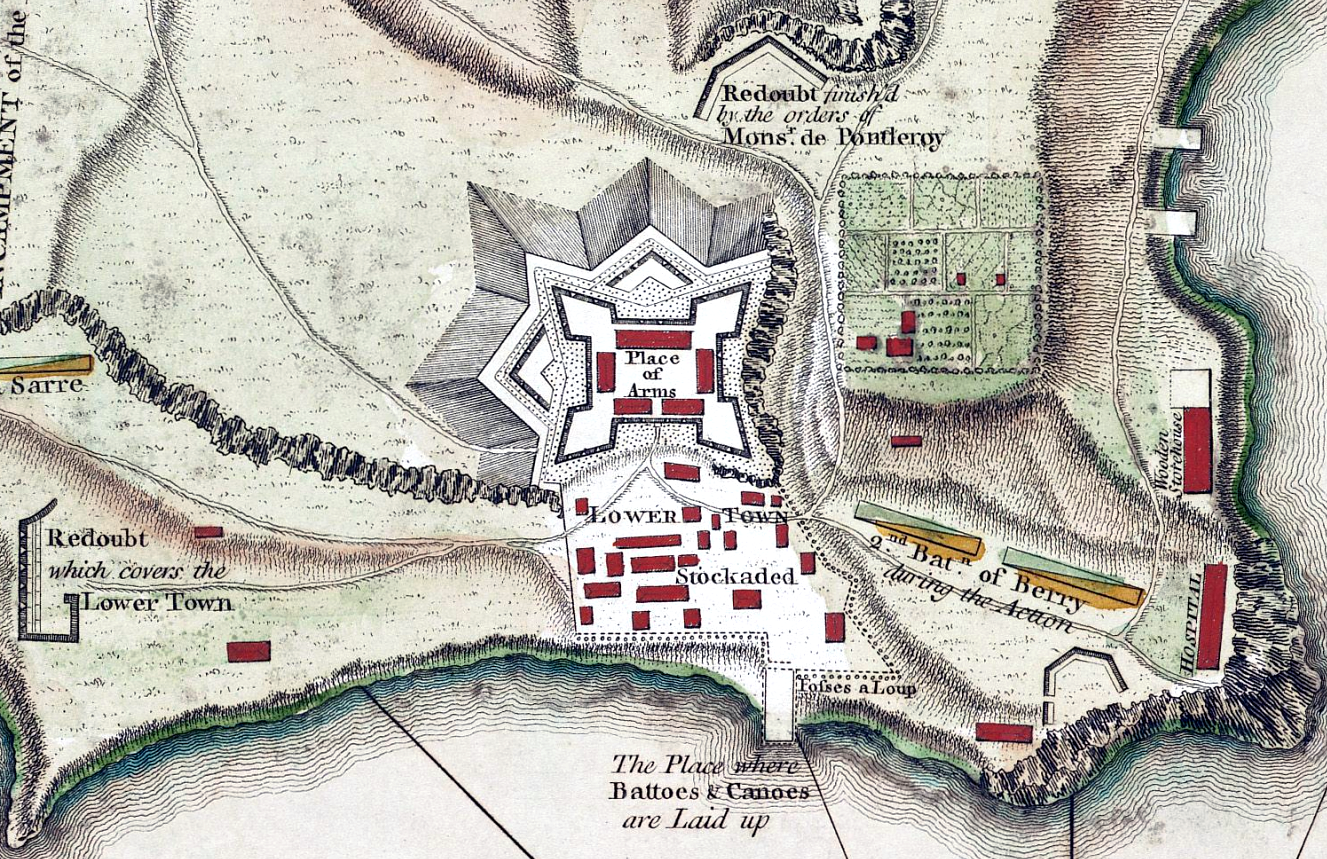

Map showing details of Fort Ticonderoga (then known as Fort Carillon) in 1758. (Thomas Jefferys, Library and Archives of Quebec)

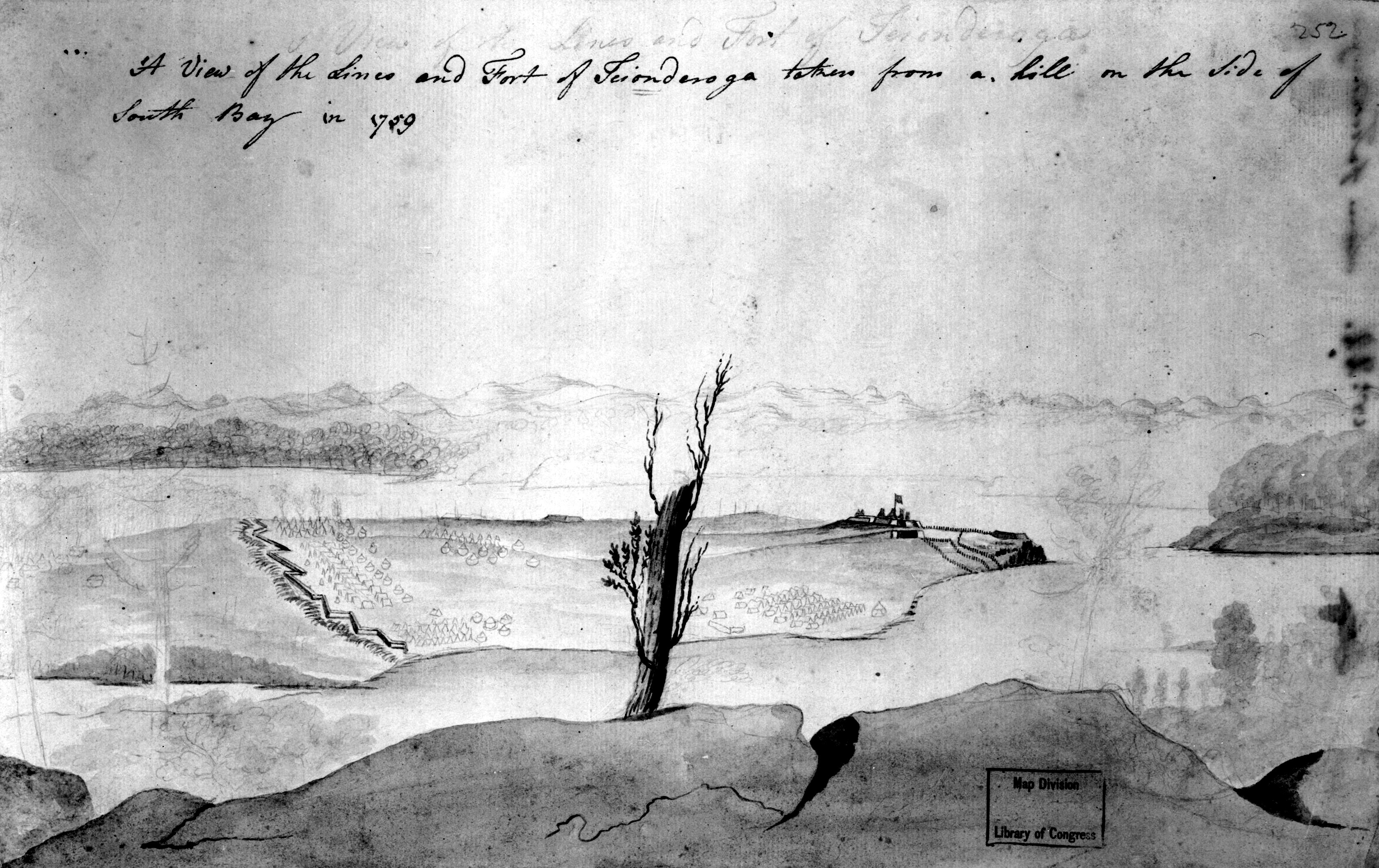

Topographical drawing of Fort Ticonderoga, drawn in 1759 from the South Bay of Lake Champlain in New York state during the French and Indian War. The tents marking military encampment are penciled in. Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.

Fort Carillon – Ticonderoga

The fight to come at Fort Ticonderoga would not be the first time a battle had taken place on the site. On the 29th of July 1609, Samuel de Champlain fought the Iroquois there. Although he would eventually seek to make himself a friend of the Iroquois, on that date he and his Indian allies encountered a band of 200 Mohawks. The two opposing forces built barricades and exchanged insults, much as present day belligerents do. The next day, Champlain and his forces “advanced to contact.” Champlain then fired his quadruple-shotted arquebus and killed two Mohawk chiefs, while a third was killed by another Frenchman. The Iroquois armour of wooden slats offered no protection against firearms, and in the ensuing battle some 50 Mohawks were killed. The Hurons and the Algonquins returned home exalting in their victory over their traditional enemies.[1]

136 years later during the course of the French and Indian War, a talented French-Canadian military engineer named de Lotbinière proceeded to build a star-shaped fortress of stone, earth and timber on this same site. It stands on a rocky ridge near the southern end of Lake Champlain where Lake George flows into it.[2] Construction of ‘Fort Carillon’ was begun in 1755 and the basic outline of the fort was complete by the winter of 1756. Similar in construction to Fort Duquesne, there were two wooden walls around the main enclosure of Fort Carillon. The ten feet of space between the walls was filled with earth to absorb cannon shot, and they were tied to each other with cross timbers dovetailed in place. The wood for the enclosure consisted of heavy oak timbers, 14 or 14 inches square, laid horizontally one on top of the other. A major weeknes of this kind of construction was the continual rotting of the timbers. This led to the decision in 1757 to revet the timber walls with a stone veneer which would make the fort much more durable.[3]

Across the lake the new fortress faced a bluff, and a little to the south Lake George emptied into a channel that flowed through a gorge into Lake Champlain. As a result, whoever held the fort controlled the only passageway which led southward out of Lake Champlain. This route in turn led toward the Hudson River by way of Lake George, and on to Albany. The Frenchman had called his fort Carillon (a chime of bells) because of the loud splash of nearby rapids. For the same reason, the Indians called the spot Cheonderoga, which meant “Noisy.” The British called it Ticonderoga, and the Americans later called it Fort Ti.[4]

For the purpose of this story, whenever the Fort is referred by the French or in the context of their defense activities within it, the site will be called “Fort Carillon.” Whenever the British or Americans refer to it or describe their attacks on it, the site will be called Fort Ticonderoga, or simply “Ticonderoga.”

[1] John Keegan, Warpaths, Travels of a Military Historian in North America, Key Porter Books, Toronto, Ontario, 1995, p. 105.

[2] Michel Chartier, Sieur de Lotbinière, was born in Québec in 1723 and had been sent to France to study the techniques of military engineering. Marguerita Z. Herman, Ramparts, Fortification From The Renaissance to West Point, Avery Publishing Group Inc., Garden City Park, New York, 1992, p. 86.

[3] Ibid, p. 86.

[4] A.J. Langguth, Patriots, The Men Who Started the American Revolution, Touchstone, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1988, p. 260.

A schematic representation of the 1758 map by Thomas Jeffrey. (Map courtesy of Magicpiano)

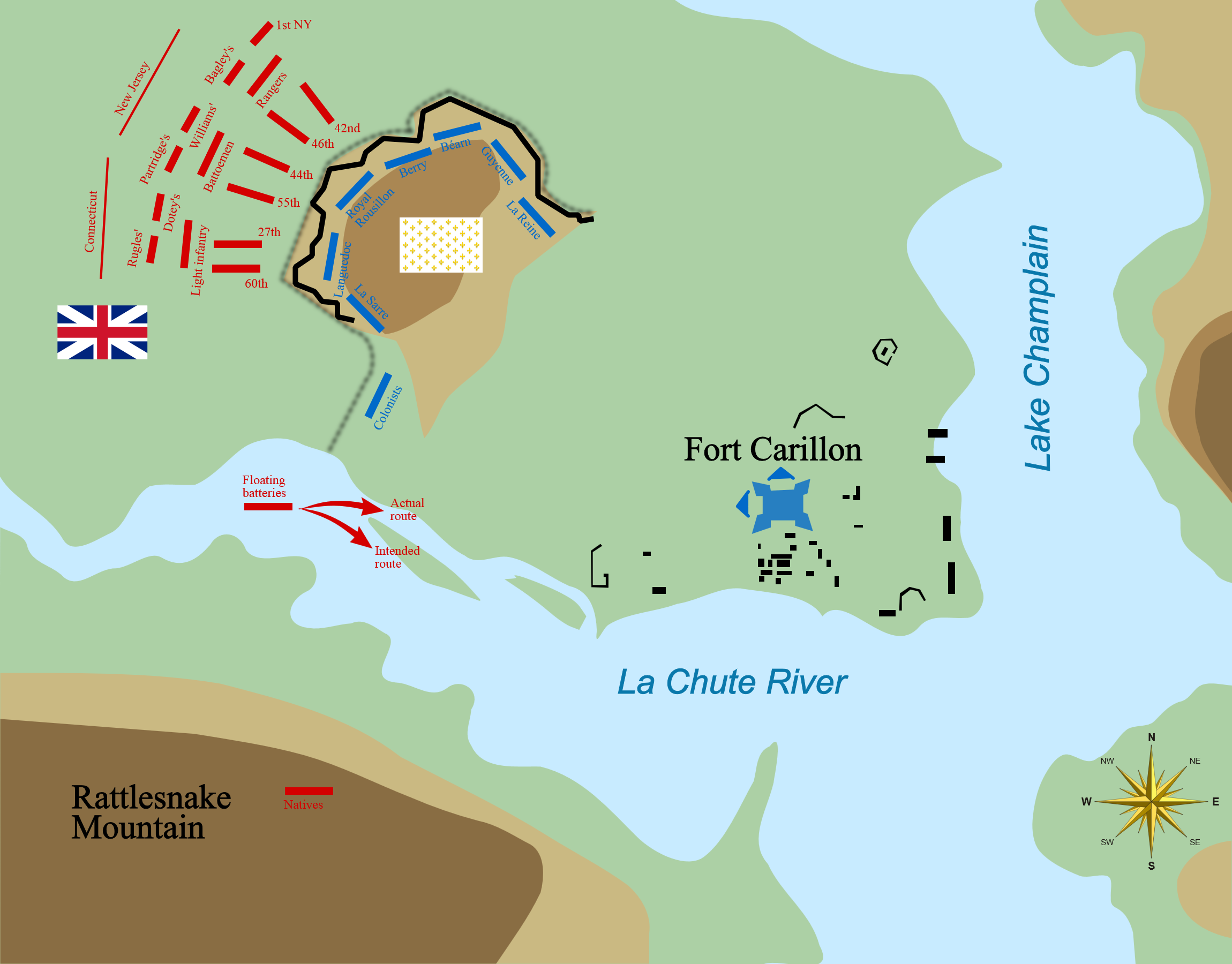

Map of the Battle of Ticonderoga on 8th July 1758 in the French and Indian War. Elijah and his fellow Massachusetts Provincial soldiers would have been standing on the south flank near the river. (Illustration by John Fawkes)

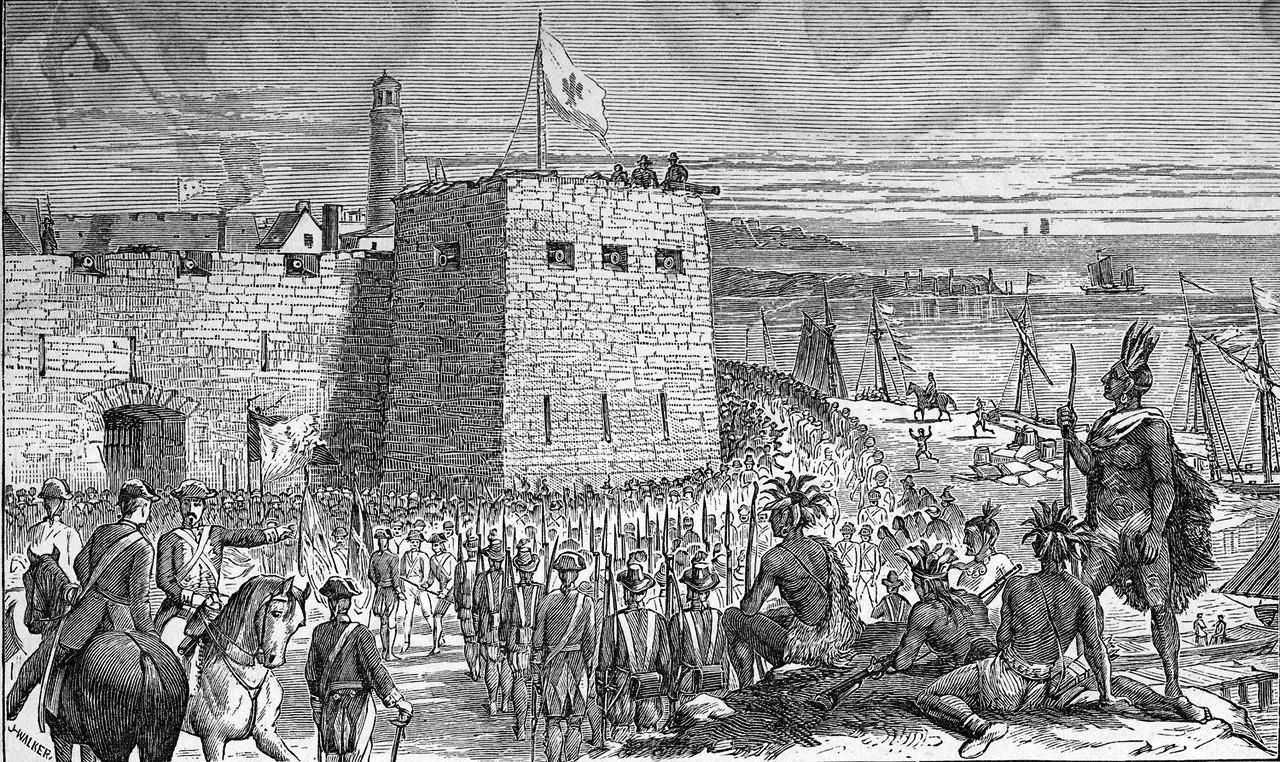

General Abercromby’s force embarking for the attack on Fort Ticonderoga 8th July 1758.

Setting the Stage for the Battle

In June 1758 a combined force of 15,350 British and Provincial soldiers commanded by General James Abercrombie were gathered at the head of Lake George near Lake Champlain, New York, in preparation for an attack on Fort Ticonderoga.[1] The commander of the French forces defending the Fort with one quarter of the numbers of troops facing him was Louis-Joseph Marquis de Montcalm-Gozon, Seigneur de Saint-Véran, who served under the Governor General of New France, Pierre de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnal.[2]

[1] Francis Parkman, The Seven Years War, A Narrative taken from Montcalm and Wolfe, The Conspiracy of Pontiac, and A Half-Century of Conflict, Harper Torchbooks, Harper & Row, Publishers, New York and Evanston, 1968, p. 184.

[2] Montcalm’s full title is Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, Marquis de Montcalm, Seigneur of Saint- Véran, Candiac, Tournemine, Vestric, Saint-Julien, and Arpaon. Baron de Gabriac, lieutenant-general. He was born at Candiac, France, on the 28th of February 1712, son of Louis-Daniel de Montcalm and Marie-Thérèse-Charlotte de Lauris de Castellance. He was mortally wounded at the Battle of Québec and died shortly afterwards on the 14th of September 1759. The Encyclopedia Americana, International Edition, Grolier Inc, Danbury, Connecticut, 1988, p. 458.

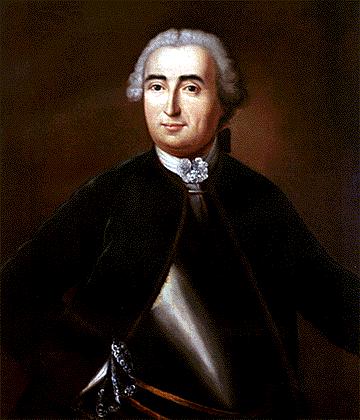

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 2895086)

Governor General Pierre François de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnal (22 Nov 1698 – 4 Aug 1778), Canadian-born colonial governor of New France.

In June 1758 a combined force of 15,350 British and Provincial soldiers commanded by General James Abercrombie were gathered at the head of Lake George near Lake Champlain, New York, in preparation for an attack on Fort Ticonderoga.[1] The commander of the French forces defending the Fort with one quarter of the numbers of troops facing him was Louis-Joseph Marquis de Montcalm-Gozon, Seigneur de Saint-Véran, who served under the Governor General of New France, Pierre de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnal.[2] Following his arrival in Canada in May 1756, Montcalm had already successfully fought and destroyed the British Forts at Oswego and George in August 1757, and demolished Fort William Henry, later made famous in the James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851) story (and a number of films), The Last of the Mohicans.[3] Montcalm prepared to meet the British assault force by deploying his men around the walls of the French stronghold with an army one-fourth the size of Abercrombie’s.[4]

Essentially these activities had become necessary because of a series of related events and battles. Governor General Vaudreuil had anticipated that there would be a renewed Anglo-American assault on Lake Ontario in February 1756. He had therefore sent 360 Canadians and Indians under the command of Gaspard-Joseph Chausegros de Léry, to harass communications between Fort Oswego and Schenectady (New York). They succeeded admirably, successfully assaulting and destroying Fort Bull (on Lake Oneida, New York) along with a vast amount of supplies. No one in the garrison was spared. Other Canadian war parties harassed Oswego all spring and early summer, preventing supplies getting through and putting the fear of God into the garrison. By July, Vaudreuil believed the time had come for the destruction of the fort itself. He sent Montcalm to Fort Carillon to inspect the new fort there, and to deceive the enemy as to his intentions. Vaudreuil assembled a force of 3,000 men at Fort Frontenac.[5]

Montcalm joined this force on the 29th of July. Before leaving Montréal he had expressed grave misgivings about the expedition, but the main problem proved to be nothing more than the building of a road to bring up the siege guns. After a short bombardment, and with the Canadians and Indians commanded by Vaudreuil’s brother, François-Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil, swarming within musket range, the garrison surrendered. 1,700 prisoners were taken, several armed ships, a large number of cannon, munitions and supplies of all sorts, and a war chest containing funds to the value of 18,000 livres. Montcalm stated the cost of the expedition had been 11,862 livres. All told, a profitable enterprise, but strategically it was worth far more than that. French control of Lake Ontario was now assured, the northwestern flank of New York was open to attack, and the danger of an assault on either Fort Frontenac or Niagara (near Youngstown, New York) had been diminished.[6]

[1] Francis Parkman, The Seven Years War, A Narrative taken from Montcalm and Wolfe, The Conspiracy of Pontiac, and A Half-Century of Conflict, Harper Torchbooks, Harper & Row, Publishers, New York and Evanston, 1968, p. 184.

[2] Montcalm’s full title is Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, Marquis de Montcalm, Seigneur of Saint- Véran, Candiac, Tournemine, Vestric, Saint-Julien, and Arpaon. Baron de Gabriac, lieutenant-general. He was born at Candiac, France, on the 28th of February 1712, son of Louis-Daniel de Montcalm and Marie-Thérèse-Charlotte de Lauris de Castellance. He was mortally wounded at the Battle of Québec and died shortly afterwards on the 14th of September 1759. The Encyclopedia Americana, International Edition, Grolier Inc, Danbury, Connecticut, 1988, p. 458.

[3] Ibid, p. 459.

[4] Francis Parkman, The Seven Years War, p. 184.

[5] Remains of this star fort still exist on the site, which is now occupied by the Canadian Land Forces Command and Staff College (CLFCSC), otherwise known as ‘Foxhole U’ at Kingston, Ontario.

[6] The Encyclopedia Americana, International Edition, Grolier Inc, Danbury, Connecticut, 1988, p. 459.

Louis-Joseph, Marquis de Montcalm-Gozon, Seigneur de Saint-Véran, Candiac, Tournemire, Pestric, St. Julien, d’Arpaon, Baron de Gabriac, Lieutenant-Général of the Armies of the King of France, Honorary Commander of the Order of St. Louis and Commander-in-Chief of the French Army in America. Born at Candiac on the 28th of February 1712, he was mortally wounded at the Battle of Quebec, and died there in Canada shortly afterwards, on the 13th of September 1759. Sergent-Marçeau, Antoine François, 1751-1847, (Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3030069)

Military Tactics in the Seven Years War

The principal weapon that came to dominate the Seven Years War was the “smooth-bore, flintlock, muzzle-loading musket, mounted with a bayonet, making it both a fire and a shock weapon.” The weapons range and complicated fire and maneuver procedures meant that it dominated the planning for the tactical deployment of troops on the battlefield of the 18th century. As would be noted by Bernard Cornwell’s 19th century officer, Major Richard Sharpe, even well-trained soldiers could fire no more than two or three rounds a minute.[1]

[1] Bernard Cornwell, Sharpe, The Legend, Video, Carleton Television, 1998.

A specific set of commands was developed to ensure the loading and firing of the Brown Bess was conducted in a “militarily correct” sequence. These orders directed the soldiers to carry out at least 12 key movements at an Officer’s command accompanied by drumbeat. “At close range, under 80 paces, a musket volley could be murderous, but at that distance there was barely time to reload before the enemy’s charge, if it were not checked, reached the line.”[1]

[1] W.J. Eccles, The French forces in North America during the Seven Years’ War, p. xvi.

As will be seen later in this story, in 1759, one double-shotted volley fired by British soldiers under General Wolfe’s command on the Plains of Abraham would be sufficient to destroy the French front line under the command of General Montcalm. The result would change the course of North American history. In the battle formations of the Seven Years War, two basic formations were employed. These were called “the line” and “the column.” The line was a military formation made up of soldiers standing in three ranks, and its effectiveness depended considerably on the coordinated fire-power given by their muskets, and the effective and highly aggressive follow up by a concerted bayonet charge against the shattered foe. An attack carried out by soldiers deployed in a column depended heavily on the shock effect of an attack against a narrow front. The object of this assault was to “pierce and shatter the enemy’s line.” The orderly deployment of troops in a line formation demanded that the supervising officers enforce the most rigorous discipline in order ensure that each and every man in the line stands fast. This discipline was the only way to ensure that a measured and coordinated volley of fire would be delivered on command against a charging foe. An attack in column also required considerable discipline to ensure that once the initial volley had been delivered, the men pressed on into the opposing hail of fire. The key to success in this usually murderous advance, was that the swifter the men assaulted forward to their objective, the fewer the number of enemy volleys they had to endure. The British army relied on the line; the French, however, at this time still believed in the effectiveness of the column. Their commanders believed that “the charge with the arme blanche” was better suited to the capabilities and the morale of their poorly trained troops with “their impetuous temperament.”[1]

Elijah Estabrooks as well as his fellow Massachusetts Provincial soldiers who deployed to Ticonderoga, were equipped with the “Brown Bess” musket.[2] According to the historian C.P. Stacy, the British musket commonly called the “Brown Bess” underwent some modifications between its introduction in the 1720s and its official replacement in 1794. The French, for their part, placed a lot of confidence in their 1754 pattern “Charleville” musket. It would appear, however, that the British felt that the Brown Bess musket was a more effective weapon based on their experience in the Quebec campaign. In a letter that Brigadier George Townshend wrote to Major-General Jeffery Amherst on the 26th of June 1775, he stated, “I recollect that in our service at Quebec, the superiority of our muskets over the French Arms were generally acknowledged both as to the Distance they carried and the Frequency of the Fire.”[3]

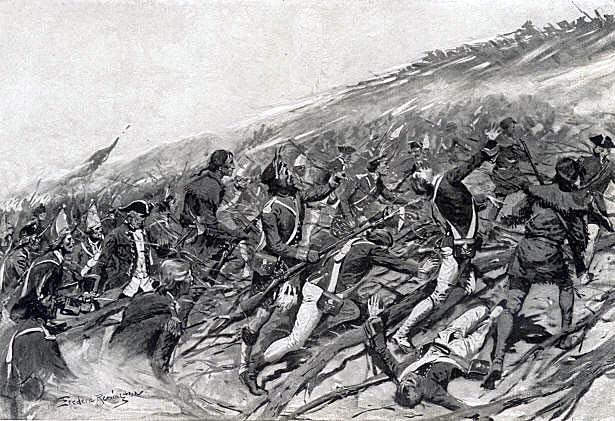

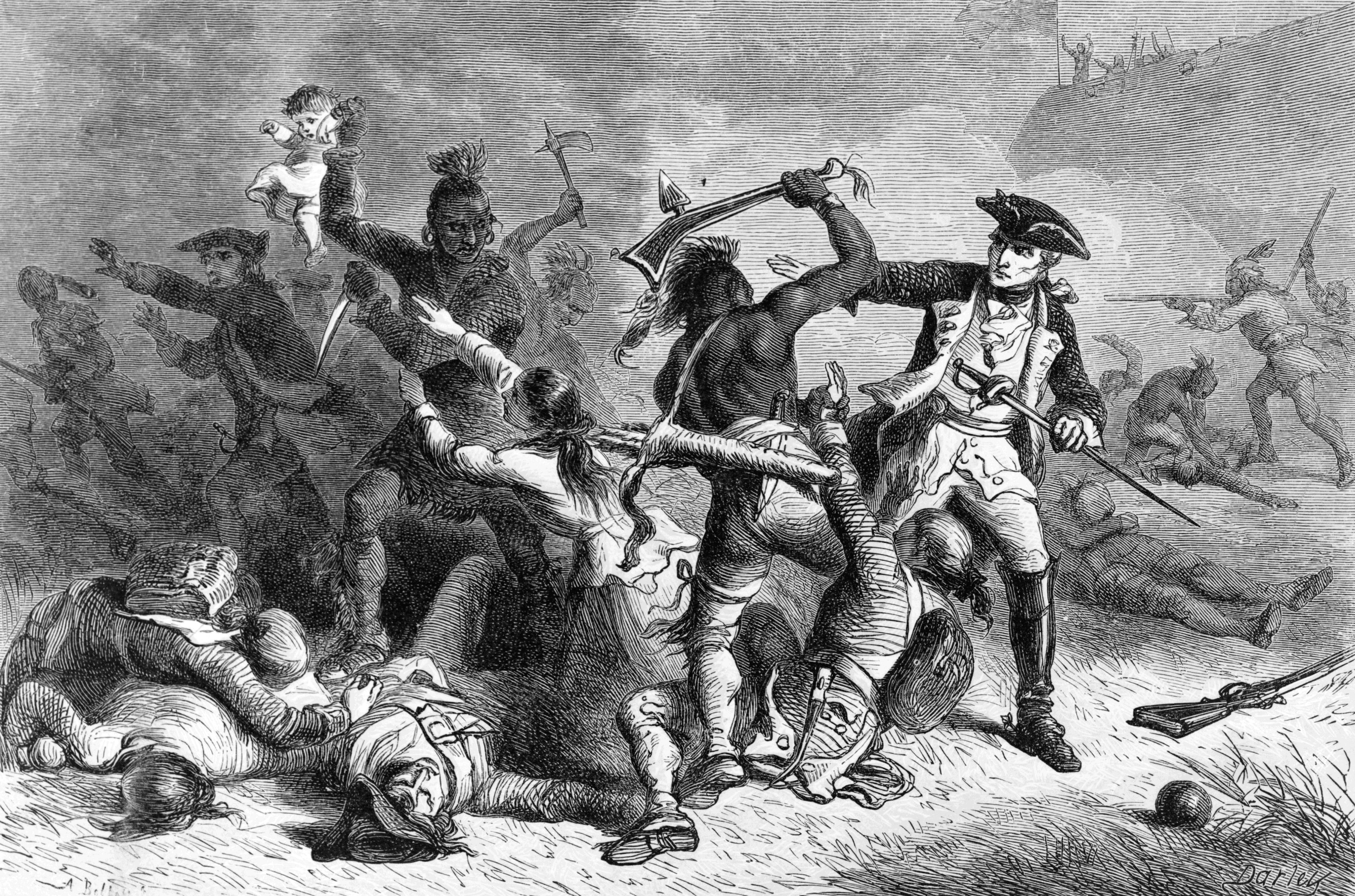

British attack at the Battle of Ticonderoga on 8th July 1758.

[1] It took a lot of drill and training to successfully maneuver troops around and onto a battlefield. At least 18 months of basic training on the drill ground was required before they could be relied on to attack in a fixed line or a disciplined column. The constant drill continued until the soldiers became virtual automatons. Even then, it was felt that a solider would need at least five years of experience before he could become “dependable” in battle. W.J. Eccles, The French forces in North America during the Seven Years’ War, p. xvi.

[2] The Brown Bess flintlock musket was the standard weapon of the British army from the 1730’s until 1794. The first model of the Brown Bess or Long-Land Musket (its regulation name), had a 46 inch barrel with a wooden rammer retained by three pipes of equal size and a tail-piece where it entered the stock. At this point the stock swells out and, generally speaking, the bigger the swell, the older the gun. One sling swivel is fastened to the front of the trigger guard bow and the other is screwed through the muzzle end of the stock between the first and second pipes. The lock of the Brown Bess was of a round pattern about seven inches long with a drooping tail. This bend gets less pronounced in the later models until, towards the end of the century, the bottom edge of the lock is practically straight. The bayonet which went with the musket had a socket about four inches long and a triangular blade 17 inches long. Another pattern of which there is increasing mention from 1740 onwards is the Short Land musket, with the same style of lock, stock and furniture as the Long model, but with a 42-inch barrel. There were soon two standard pattern muskets in production, the Long Land with steel rammers and the Short Land with wood rammers, a curious distinction between the two being that only the short pattern had a brass nose cap. By the middle of the century, however, an improved pattern noseband, or cap was fitted to both types of muskets. Internet: British Firearms, http://www.digitalhistory.org/bfirearms.html, p.1.

[3] C.P. Stacy, The British forces in North America during the Seven Years’ War, p. xxvi.

British Land Pattern Musket commonly referred to as “Brown Bess”. The musket was used from 1722 to 1838. (Photo courtesy of Antique Military Rifles)

French Charleville Musket, 1766. (Photo courtesy of Antique Military Rifles)

British Acquisition of Dutch Arms

The British, facing shortages of arms, particularly during the French & Indian War, regularly purchased Dutch muskets and cannons, including a significant shipment of 18,000 “Dutch/Liege” muskets in 1741 for distribution to their American colonies. (Annie Redford)

Elijah’s Military Service

Elijah did two tours of duty with the Massachusetts Provincials, coming out of the army after his first period of service on the 7th of November 1758 and later re-enlisting on the 6th of April 1759. During his second period of service, he was sent by ship to Halifax where he remained until the 25th of November 1760. While he was on duty in Halifax, Elijah served in a Company commanded by Captain Josiah Thatcher as part of a Regiment commanded by Colonel Thomas.[1] Their primary task was the boarding and seizure of French ships re-supplying the soldiers of New France. Elijah also served alongside other provincial soldiers from New England, most notably members of Roger’s Rangers. He was promoted to the rank of Sergeant. His family, however, remained in Boxford, Massachusetts, where he returned at the end of his second period of service.

After completing his military service Elijah Estabrooks eventually came to settle on the Saint John River. In 1762, the government of Massachusetts sponsored a group of men to participate in early exploration of the area around Maugerville in what is present day New Brunswick, in search of suitable settlements. Elijah was one of these early explorers. Early in 1763 he moved his family to Halifax and then on to Cornwallis, Nova Scotia, and later to Maugerville Township. Maugerville was still part of Sunbury County, Nova Scotia in 1763.

Elijah eventually settled on a farm near Conway, a small community just north of the present-day city of Saint John, in 1775. This was before the mass influx (some called it an invasion) of the Loyalists who had to withdraw from New England after the close of the American Revolutionary War of Independence. It was the Loyalists who renamed the newly created province of New Brunswick (NB) after King George III’s German State of Braunschweig. The Loyalists in some cases forced the existing English settlers off their land grants, and therefore many of them moved to sites further up the river. Elijah’s family was one of these, and thus he and his family eventually came to establish themselves on farms located near the village of Jemseg, which is not far from the present day Combat Training Centre (CTC), on Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Gagetown in Oromocto. Elijah later moved to a farm near Swan Creek, NB, where he died about the 11th of August 1796. Many of Elijah’s descendants are alive and well today, and can be found not only in New Brunswick, but also across Canada and the United States.[2]

[1] A company was a unit of 40 to 100 men, led by 3 commissioned officers (a captain assisted by a lieutenant and an ensign) and 7 noncommissioned officers (3 sergeants and 4 corporals). Ten companies made up a battalion, the basic tactical unit of the army. The army’s principal administrative echelon was the regiment, which could consist of from one to 4 battalions. The regiment was headed by 3 “field officers,” a colonel, a lieutenant-colonel, and a major. There were 30 company officers for the line as well as 6 administrative staff officers. Staff officers included the adjutant, who supervised personnel matters; the commissary and the quartermaster, who were responsible for the acquisition, storage, and distribution of food and materiél; the chaplain; and the surgeon and surgeon’s mate. An armorer and armorer’s mate were also attached to the staff, but they were regarded as technicians rather than officers. A regiment’s total strength could vary in size from 400 to 1,000 men, plus officers. Virtually all the Massachusetts provincial soldiers were infantrymen (the British regular units had cavalry, grenadiers, dragoons or light infantry). Fred Anderson, A People’s Army, pp. 48-49.

[2] The original material found in Elijah’s journal was copied from the Estabrooks-Palmer family records, and compiled along with other genealogical records by Florence C. Estabrooks, of Saint John, NB, on the 23rd of February 1948. Elijah’s original manuscript had passed through many hands and several leaves are missing out of the first portion of the book. Florence Estabrooks stated the data she compiled had been “copied from the journal kept by Elijah Estabrooks, a non-commissioned officer (Sergeant) in the Colonial Army during the Old French (and Indian) War which terminated in 1760-61.”

Background to the French and Indian War

The Seven Years War has been described as a worldwide series of conflicts, which were fought between 1756 and 1763. The initial object of the war was to gain control over Germany and to achieve supremacy in colonial North America and India. The war involved most of the major powers of Europe, with Prussia, Great Britain, and Hannover on one side and Austria, Saxony (Sachsen), France, Russia, Sweden, and Spain on the other. The collective series of battles fought during this war in North America became kno wn as the French and Indian War. Essentially the French and Indian war pitted Great Britain and its American colonies against the French forces of New France and their Algonquin Indian allies.[1]

The opening shots of the war in North America were fired in 1754. A rivalry between the colonies of France and England had gradually developed over the lucrative fur-trading posts and the rich lands west of the Appalachian Mountains, as well as over valuable fishing rights off the coast of Newfoundland. The French hoped to contain British settlement, particularly in the Ohio Valley, where Virginia planters had established fur-trading posts in 1749 by a strategy of encirclement. France hoped to unite itself with its Indian allies through a chain of forts, which ran as far south as New Orleans and thus prevent British expansion to the west.[2]

For the first two years of the war, French forces and their and Native Indian allies were largely victorious, winning an important and surprising victory with the defence of Fort Duquesne. In 1757, however, the British statesman William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, and a pro-Prussian, was placed in charge of Britain’s foreign policy. One of his first acts was to appoint General James Wolfe to command the British troops in the New World. The long-term result of Pitt’s bold strategy was the ultimate defeat of the French forces in North America by 1760, and the ceding of all of French Canada to Britain.[3]

[1] “Seven Years’ War,” MicrosoftâEncartaâOnline Encyclopedia 2000, http://encarta.msn.comã1997-2000 Microsoft Corporation.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

Major-General James Wolfe (1727-1759). Wolfe portrait. (Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 289499

As for General James Wolfe, he has been described by Horace Walpole as “a young officer who had contracted a reputation from his intelligence of discipline, and from the perfection to which he had brought his regiment. The world could not expect more from him than he thought himself capable of performing. He looked upon danger as the favorable moment that would call forth all his talents.” (Oliver Warner, With Wolfe to Québec, The Path to Glory, Collins, Toronto, 1972, p. 28.)

The Seven Years War officially ended on the 10th of February 1763 with the Treaty of Paris, which was signed to settle differences between France, Spain, and Great Britain.[1] Among the terms was the acquisition of almost the entire French Empire in North America by Great Britain. The British also acquired Florida from Spain and the French retained their possessions in India only under severe military restrictions. The continent of Europe remained free from territorial changes.[2]

[1] The Treaty of Paris ceded all of Canada to Britain, leaving France with only the small islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon, which permitted her to maintain a tiny foothold in the lucrative fishing region. Under the Treaty, France also kept part of Louisiana. The National Post, 10 February 2000. The Key points of the treaty are as follows:

Article IV of the Treaty states, “His Most Christian Majesty renounces all pretensions which he as heretofore formed or might have formed to Nova Scotia or Acadia in all its parts and guarantees the whole of it, and with all its dependencies, to the King of Great Britain; Moreover, his Most Christian Majesty cedes and guaranties to his said Britannic Majesty, in full right, Canada, with all its dependencies, as well as the island of Cape Breton, and all the other islands and coasts in the gulf and river of St. Lawrence, and in general, every thing that depends on the said countries, lands, islands, and coasts, with the sovereignty, property, possession, and all rights acquired by treaty, or otherwise, which the Most Christian King and the Crown of France have had till now over the said countries, lands, islands, places, coasts, and their inhabitants, so that the Most Christian King cedes and makes over the whole to said King, and to the Crown of Great Britain, and that in the most ample manner and form, without restriction, and without any liberty to depart from the said cession and guaranty under any pretense, or to disturb Great Britain in the possessions above mentioned. His Britannic majesty, on his side, agrees to grant the liberty of the Catholic religion to the inhabitants of Canada: he will, in consequence, give the most precise and most effectual orders, that his new Roman Catholic subjects may profess the worship of their religion according to the rites of the Romish church, as far as the laws of Great Britain permit. His Britannic Majesty further agrees, that the French inhabitants, or others who had been subjects of the Most Christian King in Canada, may retire with all safety and freedom wherever they shall think proper, and may sell their estates, provided it be to the subjects of his Britannic Majesty, and bring away their effects as well as their persons, without being restrained in their emigration, under any pretense whatsoever, except that of debts or of criminal prosecutions: The term limited for this emigration shall be fixed to the space of eighteen months, to be computed from the day of the exchange of the ratification of the present treaty…” The complete text of the Treaty of Paris can be found at: http://www.solon.org/Constitutions/Canada/English/PreConfederation/Treaty_of_Paris_1763.html, and in “The History of Nova Scotia,” p. 14.

[2] “Seven Years’ War,” Online Encyclopedia 2000, http://encarta.msn.comã1997-2000 Microsoft Corporation.

Louisbourg and the Seven Years War

Four periods of war had dominated life in North America during the late 17th and early part of the 18th centuries. King William’s War was fought between 1689 and 1697, and followed only five years later by Queen Anne’s War fought between 1702 and 1713. Less than a dozen years later, Governor Dummer’s War was fought between 1722 and 1725, followed by the fourth conflict, King George’s Wars which took place between 1744 and 1748. By this time, the people of Massachusetts had contributed more than their share of blood and treasure in support of England’s worldwide conflict with France. The Seven Years War would see the cost rise even higher for the New England colony.[1]

When France lost Port Royal (in what is present day Nova Scotia) in the Treaty of Utrecht, it proceeded to spend six million in gold building the “impregnable” fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island.[2]

In many ways, the great fortress of Louisbourg was a memorial to the fortress-designing genius of Vauban. This is because two of his pupils, Verville and Verrier, made extensive use of Vauban’s ideas and designs to make the fortress one of the greatest strongholds of New France. Louisbourg was built on a narrow headland, with water on three sides. The sea itself provides a moat, and on nine days out of ten the surf pounds hard on the rock-strewn Nova Scotia shore. Beyond the shore there is a string of shoals and islands that reduces the harbour entrance to a mere 400 yards, and this in turn offers the defender numerous well-sited positions for gun emplacements that would command the roadway and the only channel entrance into Louisbourg’s harbour. In its heyday, a marsh lay to the landward side of the fortress, and this would have caused any heavy artillery that the British needed to employ to bog down. Even then, there are only a few low hillocks that offer would offer a useful position to mount and site the guns that had been dragged into position. Using Vauban’s principles, the fortresses walls were ten feet thick, and faced with fitted masonry that rose thirty feet behind a steep ditch. This defence in turn was fronted by a wide glacis, with an unobstructed sloping field of fire that could rake a designated killing ground at pointblank range with cannon and musket shot. The fortress was equipped with 148 cannons, including 24 and 42 pounders, and positioned to allow all-round fire or massive concentrations at selected danger points. The defenders were also sheltered inside the fortress with “covered ways,” which protected them from bombardment splinters.[3]

In spite of its solid design, however, on the 20th of April 1745 (during King George’s War), the English conducted a successful amphibious landing and siege of the fortress of Louisbourg. The operation was conceived by Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts and carried out by the New England militia led by William Pepperell, a merchant of Kittery, Maine, and the Royal Navy, which supported him with a blockading squadron under Admiral Sir Peter Warren. Following a six-week siege, the French commander surrendered the fortress (at a time when it was known as “the Gibraltar of the New World”), on the 16th of June 1745.[4]

Sometimes an almost ridiculous element of chance had a major role to play in the successful outcome of a siege. During the first siege of Louisbourg on the 28th of May 1745, the combined forces of William Pepperell and Admiral Warren lacked the heavy cannon needed to reduce the fortifications of the Gabarus island battery blocking access to the harbour defences. During a reconnaissance by a landing party, a sharp-eyed man looking down into the clear water saw what incredibly appeared to be a whole battery of guns half hidden in the sand below. This is exactly what it was, ten bronze cannon which had slid from the deck of a French “Man o’ War” years earlier and had been left in the water by the profligate Governor. The men swiftly raised the guns, scoured them off, hoisted them onto the headland and were soon blasting shot across the half-mile gap onto the French battery. When one shot finally hit the island’s powder magazine, the French Commander d’Aillebout had to give up. With this position in hand the siege was then brought to a successful conclusion after 46 days. After Louisbourg’s surrender, Admiral Warren put the French flag back up. Thus, French ships kept sailing into Louisbourg’s harbour, including one carrying a cargo of gold and silver bars. 850 guineas were given to every sailor as prize money.[5]

Capturing Louisbourg and holding it were two different matters in the world of European politics. Diplomacy lost what valour had won, and in the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748, which concluded this war with France and Spain, Louisbourg was returned to the French. This meant that Louisbourg had to be retaken during the Seven Years War.[6]

The Second Siege of Louisbourg took place between the 1st and 26th of July in 1758. On this occasion, the French forces of Governor Augustin de Droucourt defended the fortress with 3080 men and 219 cannon against the combined forces of Major-General Jeffery Amherst and Admiral Edward Boscawen. With 25,000 men and 1842 guns afloat, some 200 ships left England in February 1758 with orders to take Canada. Brigadier General James Wolfe was one of the three brigade commanders onboard. The force conducted amphibious training in Halifax before sailing to Louisbourg where a 49-day siege was successfully carried out. The fortress had been bombarded to the point where the defenders were left with only three cannons able to fire, at which point Governor Augustin surrendered. Shortly afterwards, the task force set off to take Québec, which fell on the 13th of September 1759. In this case, one successful siege led to the staging of the next, in a domino effect that ultimately resulted in far reaching changes to the nation of Canada.[7]

[1] With the exception of Governor Dummer’s War, these conflicts were all American phases of ongoing European conflicts, which included the War of the League of Augsburg ((1689-1697); the War of the Spanish Succession (1702-1713); and the War of Jenkins’ Ear – also known as the War of the Austrian Succession (1739-1748). Fred Anderson, A People’s Army, Massachusetts Soldiers and Society in the Seven Years’ War, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London, 1984, p. 3.

[2] Construction on the fortress was begun by Michel-Philippe on the 7th of March 1719. The National Post, Toronto, 07 March 2000, History of Nova Scotia. Internet, http://www.alts.net/ns1625/nshist01.html, p. 6.

[3] Leslie F. Hannon, Forts of Canada, The Conflicts, Sieges, and Battles that Forged a Great Nation, Toronto, McClelland and Stewart Ltd, 1969, p. 30.

[4] Ibid, p. 30.

[5] Leslie F. Hannon, Forts of Canada, p. 30.

Great Britain reimbursed Massachusetts for the entire cost of the expedition, Á183,649 sterling, which was the largest reimbursement in the history of the province. The sum was paid in coin, which in 1750 was used to provide a specie base for a reformed provincial currency, the Lawful Money that replaced Massachusetts’ greatly depreciated Old Tenor paper money. The disbursement of the coins halted the inflation that had plagued the colony for most of the century. Fred Anderson, A People’s Army, pp. 9-10.

[6] Ibid, p.30.

[7] Ibid, p.30.

William Pitt

On the 29th of June 1757 William Pitt (1708-1778, Earl of Chatham in 1766) became secretary of state and Prime Minister. An able strategist, “Pitt saw that the principal objective for England should be the conquest of Canada and the American West, thus carving out a field for Anglo-American expansion.”[1]

[1] Samuel Eliot Morison, The Oxford History of the American People, New York, 1965, p. 165.

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham (1708-1778).

On the 29th of June 1757 William Pitt (1708-1778, Earl of Chatham in 1766) became secretary of state and Prime Minister. An able strategist, “Pitt saw that the principal objective for England should be the conquest of Canada and the American West, thus carving out a field for Anglo-American expansion.”[1]

A great number of William Pitt’s predecessors had been largely incompetent. His immediate predecessor for example, had been more interested in the distribution of patronage and the benefits he could gain by them rather than in conducting the affairs of the state. Bluntly stated, he used and abused the Parliament rather than serving it. Pitt was not cast from the same mold. He was an honest, devoted, and able man, but more importantly, he had the great gift of being able to find other men like himself and to inspire them to do great things. Like Cromwell, he “had his warts.” He enjoyed “putting on a show.” He was theatrical, self-assured, and sometimes pompous. He was also sometimes quite extravagant which in turn often put him in a difficult financial position. On top of this, he had an “overweening pride.” It was not his arrogance or the pride, however, that the British people both at home and in the colonies, had come to know and respect. Pitt had taken action to restore order where there had been serious discord. One example of this was the fact that the English hated and feared the Scots, due the troubles that had stemmed from the uprisings of the Jacobites.[2]

Not much more than a dozen years had passed since the Scottish clans had threatened the security of England. Because of this, the general English population wanted restrictions maintained against the Scots and the threat they posed. Instead of destroying the clans, Pitt responded to this difficult issue by employing Scottish soldiers in the service of Britain. He raised regiments from among them to serve a common country. Because of this, Elijah Estabrooks would find himself and his fellow Colonial soldiers at Ticonderoga fighting alongside Scottish regiments such as the famed “Black Watch.” The highlanders would play a dramatic part in the story of the fight for Canada. Another bone of contention in the colonies, which Pitt dealt with, was the wiping out of the social snobbery which gave a British regular officer seniority and rank over any position held by their colonial counterparts.[3]

Pitt made a number of critical decisions, which in turn had an immediate effect in North America. One of his first acts was to recall an incompetent military commander, the Earl of Loudoun. For almost the same reasons, he would also have removed General Abercrombie, but this officer apparently had better or more aggressive friends. Instead of stirring up a hornet’s nest of dissension in a relatively short a space of time, Pitt decided on an alternative course of action. He sent out Lord Howe to be Abercrombie’s second-in-command. Pitt seemed certain that Howe would eventually come to “dominate the older man and so assume command in fact, if not in name.” Wolfe, writing to his father, had called Howe “the noblest Englishman that has appeared in my time and the best soldier in the army.” Pitt must have been satisfied at Wolfe’s comment, as he also had a great deal of confidence in this young brigadier’s judgment.[4]

[1] Samuel Eliot Morison, The Oxford History of the American People, New York, 1965, p. 165.

[2] On the 16th of April 1746, Scottish Jacobites, who were followers of Prince Charles Edward fought against King George the Second’s son, the Duke of Cumberland in the Battle of Culloden Moor. The Dukes 10,000 men and artillery defeated every Highland charge. His cavalry then counter-attacked and proceeded to slaughter the Jacobites.

[3] Joseph Lister Rutledge, Century of Conflict, The Struggle Between the French and British in Colonial America, Volume Two of the Canadian History Series, Edited by Thomas B. Costain, Doubleday & Company Inc., Garden City, New York, 1956, p. 448.

[4] Ibid, p. 449.

General Jeffrey Amherst (1717-1797) painted in 1765 by Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792)

Pitt selected Jeffery Amherst, (whom Elijah mentions in his diary), to be his “commander in chief in America.”[1] Amherst apparently was “solid and unemotional, and had the right character to neutralize the impetuosity of Wolfe.” Amherst, Wolfe, and Admiral Boscawen, in July 1758 recaptured a much more strongly fortified and skillfully defended Louisbourg than what the British had faced in 1745. That same year a force of New Englanders under the command of Colonel John Bradstreet, (also mentioned by Elijah in his Journal) captured Fort Frontenac, which was strategically sited at a point where the St Lawrence flows out of Lake Ontario. Shortly after these major battlefield successes, Brigadier John Forbes, with George Washington on his staff, marched across Pennsylvania and captured Fort Duquesne, renaming it Pittsburgh after their esteemed British “war” minister.[2]

The earliest authenticated portrait of George Washington shows him wearing his colonel’s uniform of the Virginia Regiment from the French and Indian War. The portrait was painted about 12 years after Washington’s service in that war, and several years before he would return to military service in the American Revolution. Oil on canvas. (Charles Willson Peale – Washington-Custis-Lee Collection, Washington and Lee University, Lexington)

Pitt steadfastly refused to delegate any authority to his subordinates, and equal self-assurance he overrode the intense dislike the British regular officers had of employing large numbers of provincial soldiers. He was convinced that only vast numbers could decisively defeat the French forces in North America, and therefore insisted that the colonies raise large numbers of provincials every year, in spite of the fact that his regular field commanders regarded them as somewhat of a burden.[3]

Sir William Johnson.

Elijah rejoined the Colonial Army on the 6th of April 1759, the same year that Britain won many of the war’s most famous battles. A well-conducted amphibious operation in the West Indies had led to the fall of Guadeloupe, for example. The French power in India had been destroyed. In addition, a French fleet that had been intended to reinforce Canada had been destroyed at Quiberon Bay by Admiral Sir Edward Hawke. Fort Niagara, which was the key to the Great Lakes, was captured by the British with the help of Sir William Johnson and his Iroquois braves. Above and beyond these successes, however, was the campaign that ultimately led to the siege and capture of Québec.[4]

The Battle of Quiberon Bay, 20 November 1759, by Richard Paton. (Royal Museums, Greenwich, UK, BHC0397)

The Battle of Quiberon Bay, 20 November 1759 The Battle of Quiberon Bay, on 20 November 1759, was the most decisive naval encounter during the Seven Years War, 1756-63, a conflict involving the major European colonial powers and fought around the globe. France had been at war with Britain since 1756, her position in Canada, India and the West Indies was on the point of collapse and in Europe she faced stalemate against Prussia, which received British support. The battle resulted in the destruction of the French Brest fleet and occurred when the French broke out of the five-month English blockade of Brest . In an attempt to solve her problems the French planned to land an army of 20,000 men in Ireland. This force was assembled largely in the gulf of Morbihan in southern Brittany under the Duc d’Aiguillon, and was to be escorted by the Brest fleet under Admiral de Conflans. Admiral Sir Edward Hawke’s Channel Fleet blockaded Brest to prevent the French leaving to collect the troop transports, but during a gale in the first week of November, Hawke’s ships were forced to run for shelter in Torbay, giving de Conflans the chance to escape. On hearing that the French had done so Hawke went in pursuit and, on 20 November, sighted him 20 miles out to sea. De Conflans, relying on local knowledge, ordered his fleet to take refuge in Quiberon Bay, south of Morbihan, assuming Hawke would not follow, both because night was quickly coming on and when he saw the area was one of ill-charted rocks, reefs and wild seas. This was a miscalculation, for Hawke relentlessly pursued him into the bay, losing two of his own ships on the outer reefs but sinking the French ‘Thesee’ outright and otherwise decimating de Conflans’ force in what became an action practically in the dark. The French flagship ‘Soleil Royal’ went aground in the bay, near Le Croisic, and was burnt the following day. Others were captured and, of the few which managed to escape into the mouth of the River Vilaine, all were trapped for months, and one more lost by grounding. This action stopped any French plans to invade Britain during the Seven Years War. The famous naval song ‘Hearts of Oak’ was composed to commemorate the battle, which was fought so close inshore that contemporary accounts reported that ten thousand persons watched it from the coast. In the central foreground is the French ship ‘Thesée’ taking her last plunge as the water breaks over her fo’c’sle. Close by on the right and still firing into the ‘Thesée’ is the English ‘Torbay’ commanded by Captain the Hon. Augustus Keppel, with her main and mizzen sails aback. On the right of the picture in the middle distance is the French ship ‘Formidable’ which is shown being taken by the English ship ‘Resolution’ astern of her. In the background seen between the ‘Torbay’ and the ’Formidable’ is a frigate, in port-quarter view. On the left of the picture in the background are the sterns of the leading division of the English warships and the rear of the French fleets sailing on the port tack and in action. The nearest two are the French flagship ‘Soleil Royal’ on the left, shown as a three-decker, firing at an English ship which is returning her fire. Curiously the painting does not include Hawke’s flagship, the ‘Royal George’. The battle of Quiberon Bay, 20 November 1759

[1] Jeffrey Amherst was only 40 and a Colonel when he was chosen to lead the British forces against Louisbourg and Quebec in 1758. Although he had never had an independent command, he had impressed the most influential generals in the British Army as an unusually dependable and persistent officer. He had entered the army at the age of 14; gone with his regiment to the Low Countries, Germany, and Scotland; won praise for his steadiness under fire at Dettingen and Fontenoy; and served as the aide-de-camp to the Duke of Cumberland in the closing campaigns of the War of the Austrian succession and in the opening campaign of the Seven Years War. He has been described as an officer with the patience, prudence, and persistence to succeed in a war of sieges and maneuver. Robert A. Doughty et al, Warfare in the Western World, Vol I, Military Operations from 1600 to 1871, Heath and Company, Lexington, Massachusetts, 1996, p. 118.

[2] Samuel Eliot Morison, The Oxford History of the American People, p. 165.

[3] Fred Anderson, A People’s Army, p. 16,

[4] Samuel Eliot Morison, The Oxford History of the American People, p. 165.

Background to the Estabrooks Family

Elijah and the Estabrooks family that settled on the Saint John River in what was then part of the Province of Nova Scotia and is now the Canadian Province of New Brunswick have a long and storied tradition. The Estabrooks name originated in Flanders, (now Belgium) where Estauberg (d’) or Estaubrugge was the name of one of the confederate nobles. He apparently belonged to the family or clan d’Estambrugge, to which Oliver d’Estambrugge, who was appointed bailiff of Ghent in 1387, belonged. Heer van Estambrugge may have been a brother of the Count Van Ligne, in which case he later broke away from the confederates, as in the latter part of 1566, he assumed command of 100 Cavalry from the National Militia, for the defense of Brussels.[1]

In the Middle Ages, several Flemish families by the name of Yandell (or Yendall) lived together long ago in the Low Countries of Europe (Holland or Flanders) in the neighborhood of Ghent or Liege. They were Dutch-Flemings. The main body of the family lived on the West Side of a stream; but a considerable number lived on the East Side at the end of a particular bridge (or bridges), and were therefore called the Estenbrugge-Yandells or briefly, the Estenbrugge.

At the time of the Reformation, (about 1517), these people became Protestants. During the religious wars that followed (about 1570-80), and the activity of the Spanish Inquisition during the latter half of the sixteenth century, they had to leave the country. A large group went together and settled in western Devon. Some used the name Yandell and some the name Estenbrugge, which gradually became Anglicized into various forms of Estabrooks.

The tradition received by one of Elijah’s descendants, Florence Estabrooks, was that the Estenbrugge family or Yandells lived in Brugges, Liege or Ghent (in present day Belgium). Another tradition, however, is that they originally lived in Holland, moved into Flanders, and after a brief stay went on to England. Both branches of the family had members who migrated to America, where they apparently kept some contact.

Joseph Estabrook of Concord, Massachusetts was born at Enfield, Middlesex County, England in 1640. His father was also probably born in England, but his grandfather may have been born in Flanders, placing the original emigration sometime between 1590 and 1600. The family must have done well in England, as Joseph was prepared for college before coming to America and took his four-year course after his arrival. His brother Thomas also did well, as he bought a large farm near Concord.

Joseph’s parents were certainly Puritans. After the death of Cromwell and the Restoration of Charles II, it was the sensible thing for a person wishing to be a clergyman in the Congregationalist Church to come to Boston, Massachusetts.

Joseph arrived in Boston in 1660 and attended Harvard College from which he graduated in 1664. In 1667 he was ordained as a colleague of the Reverend Peter Bulkeley at Concord, and on Bulkeley’s death in 1696 became pastor of the Church, continuing in that office until his death on the 16th of September 1711 at the age of 71 years. He had been made a freeman at Cambridge, Mass on the 3rd of May 1665. On the 20th of May 1668, he married Mary Mason, daughter of Captain Hugh and Esther Mason, at Watertown, Massachusetts.

The “Boston News” reported that the Reverend Joseph Estabrook “was eminent for his skill in the Hebrew language, a most orthodox, learned, and worthy divine; of excellent principles in religion, indefatigably laborious in the ministry of holy life and conversation.”

Joseph had married Mary Mason (born on the 18th of December 1640) on the 20th of May 1668 and they had six children. Joseph died on the 16th of September 1711 at the age of 71. The children of Joseph and Mary were: Joseph; Benjamin (who attended Harvard in 1690, then became a minister at Lexington, and died in 1697); Mary; Samuel (who also attended Harvard in 1696, and became a minister at Canterbury, Connecticut from 1711 to 1727); Daniel; and Ann.

Joseph (junior) was born in Concord, Massachusetts on the 6th of May 1669. He married his first wife, Millicent Woods on the 31st of December 1689, at Cambridge Farms, Massachusetts and they had six children. Millicent was the daughter of Henry W. Woods of Connecticut, and she died at Concord on the 26th of March 1692. Joseph later married Hannah Leavitt, daughter of John Leavitt of Hingham. Hannah was the widow of Joseph Loring and had a daughter by her first husband named Submit. Submit later married Joseph’s son by Millicent Woods, Joseph junior.

Joseph bought a farm of two hundred acres of land in Lexington in 1693. The Concord Road bound it on the southwest. He was an active and influential member of the Church at Lexington and represented it on many public occasions. He commanded a military company, and filled the office of town clerk, treasurer, assessor, selectman, and representative to the General Court. He was a man of more than ordinary education and was engaged to teach the first man’s school in the town. He died in Lexington on the 23rd of September 1733.

The children of Joseph and Millicent were: Joseph (the third); John; Solomon; Hannah (who married Joseph Frost of Sherburne); Millicent; and Elijah.

Elijah, son of Joseph (the second) and Hannah (Leavitt) Loring, was born in Lexington on the 25th of August 1703. He married Hannah Daniel of Sherburne (born on the 6th of April 1702), in Boston on the 1st of October 1724. Their place of residence is unknown between 1724 and 1734, and there is a tradition that after their marriage, Elijah and his wife went to England, where their son Elijah (junior) was born. It is said they returned to America in 1730.

While in England Elijah probably visited Flemish relatives, for his son Elijah (junior) was very well versed in Flemish traditions, which he told to his grandchildren. The American tradition is that the Elijah Estabrooks who came to the Saint John River was pro-British.

A short time after his return, Elijah (senior) was with his wife’s people, the Daniel’s, and his brother-in-law, Joseph Frost in Sherburne. His daughter Hannah was born in Sherburne in 1734. Not long afterwards, Elijah (senior) died on the 1st of December 1740 in Sherburne.

An entry in the Newbury, Massachusetts records states, Joseph Burril of Haverhill married Mrs. Hannah Esterbrook in Newbury on the 9th of February 1743/44. They lived in East Haverhill (Rocks Village). This Hannah may have been the widow of Elijah (senior); hence Elijah (junior), Submit and Samuel turn up in Haverhill.

Elijah senior’s journeys must have depleted his resources, as he died intestate and his estate was small. Joseph Frost administered it.

The children of Elijah and Hannah were Mary; Elijah; Deborah; Submit; Hannah; Joseph; Samuel; and Aaron.

In the Middlesex County Probate Records from Cambridge, Massachusetts, the following entry appears:

Middlesex. S.S. Guardianship to Elijah (at his election) a minor in his 19th year of age, son of Elijah Estherbrook (sic) late of Sherburne in said County Dec’d., is committed to Joseph Frost of Sherburne aforesaid. Gent. who hath given bond of 500 (pounds). Witness my hand and seal of office. Dated at Cambridge the 14th of July 1746. S. Danforth, J. Probt.[2]

Elijah (junior) was born about 1727, and as a boy before the death of his father, he must have been in Sherburne with his family between 1734 and 1740. During this time, he acquired a good education for his journal is well written. After his father’s death, his Uncle Joseph Frost or the Daniels probably looked after him. The formal guardianship assumed in 1746 was “probably a surety for him going out into the world.”[3]

Elijah soon found his way to Haverhill, Massachusetts. His mother was there and there was plenty of work in connection with shipbuilding. He was admitted to the Second Church (Congregational) at East Salisbury on the 4th of March 1750. He married Mary Hackett of Salisbury on the 14th of November 1750, with the wedding ceremony being performed at Haverhill, although it is recorded in the Second Church at Salisbury.

The family apparently lived in East Haverhill from 1750 to about 1757 as the baptisms of their first three children are recorded in the Fourth (Congregational) Church. These include Hannah, baptized on the 25th of August 1751; Molly, baptized on the 18th of March 1753, and Elijah, baptized on the 23rd of May 1756. Elijah then appears to have moved to Boxford, close to Bradford, about 1727, as baptisms of two of his children appear in the records of the Second Church (Congregational) in Boxford: Samuel, baptized on the 11th of December 1757, and Ebenezer, baptized on the 9th of September 1759.

It should be noted that dating went through a radical change in North America in 1752.[4] Also of interest is a newspaper report that on the 18th of November 1755 at 11:35 UTC (GMC), the largest earthquake in Massachusetts took place.[5]

Elijah’s wife, Mary Hackett, was born in Salisbury on the 1st of August 1728. She was the daughter of Ebenezer and Hannah (Ring) Hackett, and her family was known for their shipbuilding.

[1] CF. te Water, Confederacy of the Nobles; D11, p. 386-387.

[2] Middlesex County Probate Records (1st series), v.24, p. 157

[3] Florence C. Estabrooks, Estabrooks Family, Vol 1, Upper Gagetown, New Brunswick, c. 1948, p. 10.

[4] Normally there are 30 days in the month of September, but in 1752 there was a special September with only 19 days. The eleven days, September 2nd through to the 13th inclusive, were omitted from the calendar. This applied to Great Britain (except Scotland) and all Colonies.

Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun

1 2 14 15 16 17

18 19 20 21 22 23 24

25 26 27 28 29 30

This change was part of the conversion from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar, and applied throughout Great Britain (except Scotland) and in all territories and colonies then controlled by Great Britain. This included the Thirteen Colonies along the eastern coast of North America. The new calendar did not apply to those territories under the control of France, which included Louisbourg and Québec, because France had converted to the Gregorian calendar centuries earlier. History of Nova Scotia, Internet, http://www.alts.net/ns1625/nshist01.html, p. 9.

[5] The “Cape Ann Earthquake,” was reported from Halifax, Nova Scotia, south to Chesapeake Bay in Maryland, and from Lake George, New York, east to a ship 300 kilometres east of Cape Ann. The location of the ship is thought to be near the epicenter, because the shock was felt so strongly that those on board believed the ship had run aground. Several aftershocks occurred. The region around Cape Ann and Boston received the heaviest damage from this earthquake. Stone fences were thrown down throughout the countryside, particularly on a line extending from Boston to Montréal. New springs formed, and old springs dried up. At Scituate (on the coast southeast of Boston), Pembroke (about 15 kilometres southwest of Scituate) and Lancaster (about 40 kilometres west of Boston), cracks opened in the earth. Water and fine sand issued from some of the ground cracks at Pembroke. Internet: Largest Earthquake in Massachusetts, http://www.neic.cr.usgs.gov/neis/eqlists/USA/1755_11_18.html, and from the History of Nova Scotia, p. 10.

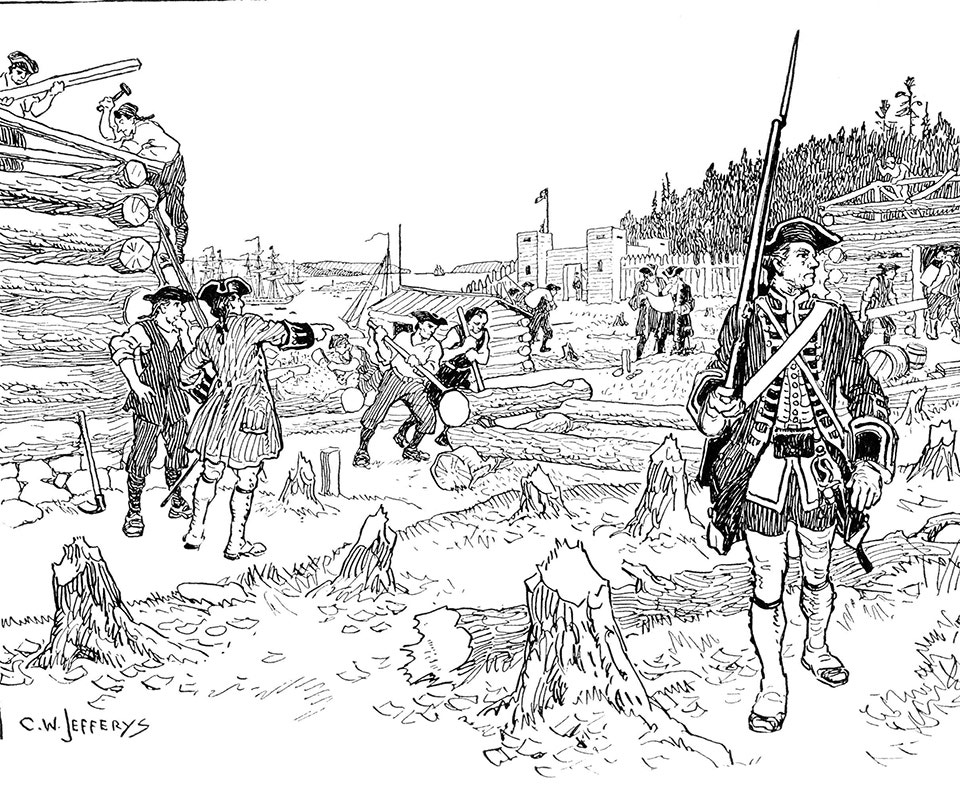

Founding of Halifax in 1749. C.W. Jeffreys.

Elijah’s diary records two periods of service; he completed his first tour of duty (after the battle at Ticonderoga) on the 7th of November 1758 and re-enlisted on the 6th of April 1759. He went by ship to Halifax and spent his second tour of duty in Nova Scotia, where he became a Sergeant. His family remained in Boxford. He left Nova Scotia on the 25th of November 1760 and arrived home on the 15th of December 1760, having completed his military service. The diary and an account of the events that took place during his tour of duty follows a brief description of the Massachusetts Provincial soldiers.

Massachusetts Provincial Soldiers

The British colonies responded to the leadership and financial encouragement of William Pitt by making a greater military effort than ever before to place large forces in the field. From an early period, the various British provinces in America had militias based on universal service, with every citizen of military age being liable to serve when required. These militias were called upon in the Seven Years War only in emergency. The provincial forces employed in the war were usually ad hoc units enlisted by the various colonial governments for the occasion and drawn from what may be called the floating population. In 1758 the crown furnished the men with their arms, equipment, and provisions; the colonial governments paid and clothed the men. In the response for the requisitions for troops, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New York responded particularly well. General Abercromby reported the strength of his army that advanced against Ticonderoga in July 1758 as “amounting to 6,367 regulars, officers, light infantry, and Rangers included, and 9024 provincials including officers and bateaux men.”[1]