The Canadian Airborne Regiment, 1969 – 1995

(York Sunbury Historical Society, Fredericton Region Museum Collection Photo)

Flag and Crest of the Canadian Airborne Regiment

Canadian Airborne Regiment

The Canadian Airborne Regiment (CAR) was a tactical formation manned from other regiments and branches. It traced its origin to the Second World War–era 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion (1 Can Para) and the First Special Service Force (FSSF) which was administratively known as the 2nd Canadian Parachute Battalion. The regiment bears battle honours on its Regimental Colours from both units, including Normandy Landing, Dives Crossing and Rhine in the case of the former, and Monte Camino, Monte Majo, Monte La Difensa/Monte La Remetanea, Anzio and Rome in the case of the latter. The Canadian Airborne Regiment was created on 8 April 1968 and was disbanded in 1995.

Combat Wings (after 1968).

Special Service Force

In 1977, 2 Combat Group combined with the Canadian Airborne Regiment to form the Special Service Force, a formation of the Canadian Army. This latter-day Special Service Force represented a compromise between the general-purpose combat capabilities of a normal brigade and the strategic and tactical flexibility that derived from the lighter and more mobile capabilities of the Canadian Airborne Regiment.

The Force was a brigade-sized command with strength of 3,500, created to provide a small, highly mobile, general-purpose force that could be inserted quickly into any national or international theatre of operations. To this end each unit in the Force had a parachute sub-unit that would be used to support the Canadian Airborne Regiment as the Airborne Battle Group. The 8th Canadian Hussars Armoured Regiment had 2 squadrons, “A” and “B,” equipped with Cougar AVGP armoured vehicles, and “D” Squadron, an armoured reconnaissance squadron equipped with M113 C& R Lynx tracked recce vehicles. In 1987, the 8th Canadian Hussars deployed to Canadian Forces Base Lahr in the former West Germany, while the Royal Canadian Dragoons replaced them in the Special Service Force at Petawawa after redeploying from Lahr. The 2nd Regiment, Royal Canadian Horse Artillery (2 RCHA), had a parachute battery (E Battery) with 105-mm L5 Pack Howitzers and from 1991, an airborne air defence troop. 2 Combat Engineer Regiment (2 CER) provided an airborne engineer troop. Command and supporting elements of the SSF Headquarters and Signals Squadron (HQ & Sig Sqn) were airborne, as were a platoon provided from 2 Field Ambulance (2 Fd Amb) and a Tactical Air Movements Section (TAMS) from 2 Service Battalion (2 Svc Bn).

In keeping with the Total Force concept that evolved in the late 1980s a number of combat arms units of the Army Reserve were assigned operational taskings to provide subordinate units in order to augment the Special Service Force when required. These sub-units were provided by units from the Central Militia Area (later re-designated as Land Forces Central Area and now known as the 4th Canadian Division). Units tasked included the Queen’s Own Rifles (QOR), elements of the 2nd Field Engineer Regiment, and a composite battery of Royal Canadian Artillery militia units. The Special Service Force’s readiness and deployability were never tested as a formation, but its units and soldiers served in operations both at home and around the world. They served overseas in Cyprus, Somalia, the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, and Namibia.

The following Units were serving in the SSF on disbandment in 1995:

- Special Service Force Headquarters and Signals Squadron

- 2nd Regiment, Royal Canadian Horse Artillery

- Royal Canadian Dragoons

- 2 Combat Engineer Regiment

- 1st Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment

- Canadian Airborne Regiment (now disbanded)

- 2 Field Ambulance

- 2 Military Police Platoon

- 2 Service Battalion

- 2 Intelligence Platoon

- 427 Tactical Helicopter Squadron

With the addition of Leopard tanks for the RCD, M109 howitzers for 2 RCHA and the addition of the 2nd Battalion, the Royal Canadian Regiment, and the disbandment of the Canadian Airborne Regiment and the resulting reduction in the parachute capability, the Special Service Force was redesignated as 2 Canadian Mechanized Brigade Group (CMBG) by a ministerial order signed on 24 April 1995. This decision and the associated reorganizing and re-equipping of the formation was a reflection of the emphasis in Canadian defence policy on general purpose capabilities at that time. With a smaller force structure, a smaller defence budget and more frequent operational taskings, it became clear that general purpose capabilities provided the best return on investment in defence . Accordingly, 2 CMBG was designed to be a mirror image reflection of its two sister formations, 1 CMBG in Western Canada, and 5 CMBG in Quebec. 2 CMBG maintains the spirit and traditions of the Special Service Force, while mastering the equipment and tactical doctrine that give it wide employability in a range of possible taskings.

Paratrooper statue by Col (Retd) André D. Gauthier, presented to the author on his posting from the Canadian Airborne Regiment in 1989.

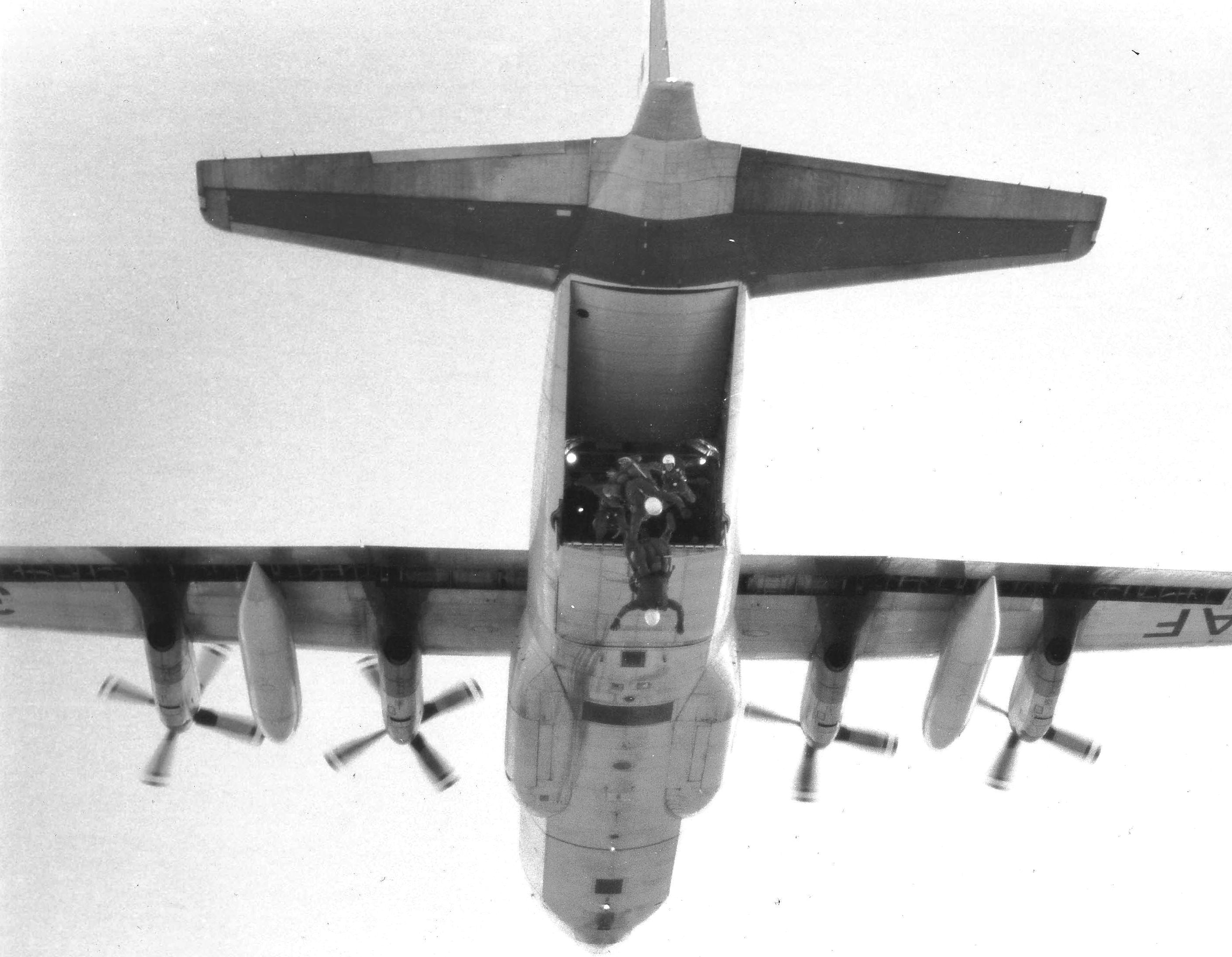

12-plane mass drop on an exercise over CFB Borden, 1988

(RCAF Photo)

Jumpers exiting a Lockheed CC-130 Hercules.

In our present time, there are often politically short-sighted reasons that a number of countries feel their military forces and defence networks do not need to be maintained. There is no quicker way to increase the vulnerability of your “fortress,” than to let your military arm be depleted to the point where it will be ineffective when you need it. Those who do so will clearly find their homelands unsafe and insecure, and highly vulnerable to attack – and there will always be some group or other who hopes to gain power over the weak. Paratroops are only one of many links in an army’s necessary suit of chain-mail. It is the spirit, élan and professionalism of these kinds of dedicated soldiers that will ensure a successful outcome to a defence or attack. To let such people be lost to the exigencies of political expedience is to diminish the chances of survival for the nations who make such decisions.

To understand how such men and women can be employed when conducting a modern operation, I would like to mention a typical exercise carried out by members of the Canadian Airborne Regiment during a training mission long before the regiment was disbanded. I would imagine that a number of similar preparations and plans have been made for operations ongoing even now around the world.

A typical airborne operation begins with the Commander’s Orders Group (O Gp). The Lockheed CC-130 Hercules aircrews, the Company/Commando Commanders and all support staffs are briefed on where, when, and how the operation will take place. The objectives are defined, the drop points selected for the first group of pathfinders who will go in to mark the drop zone and a plan is presented on how it will be defended etc. Men and equipment are “cross-loaded.” The loading is planned and mounted to ensure that not all the personnel from any one unit are placed on the same aircraft. This is to ensure that if an aircraft breaks down or crashes, there will be enough troops spread out among the other aircraft to enable the survivors to continue the mission. For example, the mortar platoon is split into two fighting elements; the tube-launched, optically-tracked wire-guided anti-tank missile (TOW) platoon is split in two fighting teams; even the Intelligence platoon with four people went on three different aircraft; the regiment’s commander is on one aircraft and his deputy (the DCO) is on another etc.[1]

Members of the Headquarters and Signals Squadron Intelligence platoon built terrain models and assembled maps and briefings to cover the objectives. In preparation, the Company Commanders would gather their Commandos, which were comprised of about 120 paratroops, with about 730 soldiers in the Regiment (a regular Infantry Company would have about 250 soldiers, an Infantry Battalion would have about 650, and there would normally be about 2,000 in an Infantry Regiment). The Commandos would gather together for a collective briefing on the operation to come. Each unit Commander would brief his individual Commando with all 120 men seated in front of the terrain model.

Every man is required to know every detail of the plan, because if some of them don’t make it to the drop-zone or the objective, others will have to fill in the gaps or carry out alternate plans. Some will have the task of covering the drop zone with heavy weapons, some will be designated to take out guard towers, sentries, control and access points, while others cover the entrances and exit or extraction points. Some will destroy buildings, aircraft, fuel and supply dumps and power sources, others may be designated to take prisoners, release hostages, carry out medical evacuations (Medevac) etc. If it is to be a combat extraction, the operation on the ground will last no more than a few hours. Every man participating in the briefing is expected to understand the plan, and if only a few get through, the plan still goes ahead.

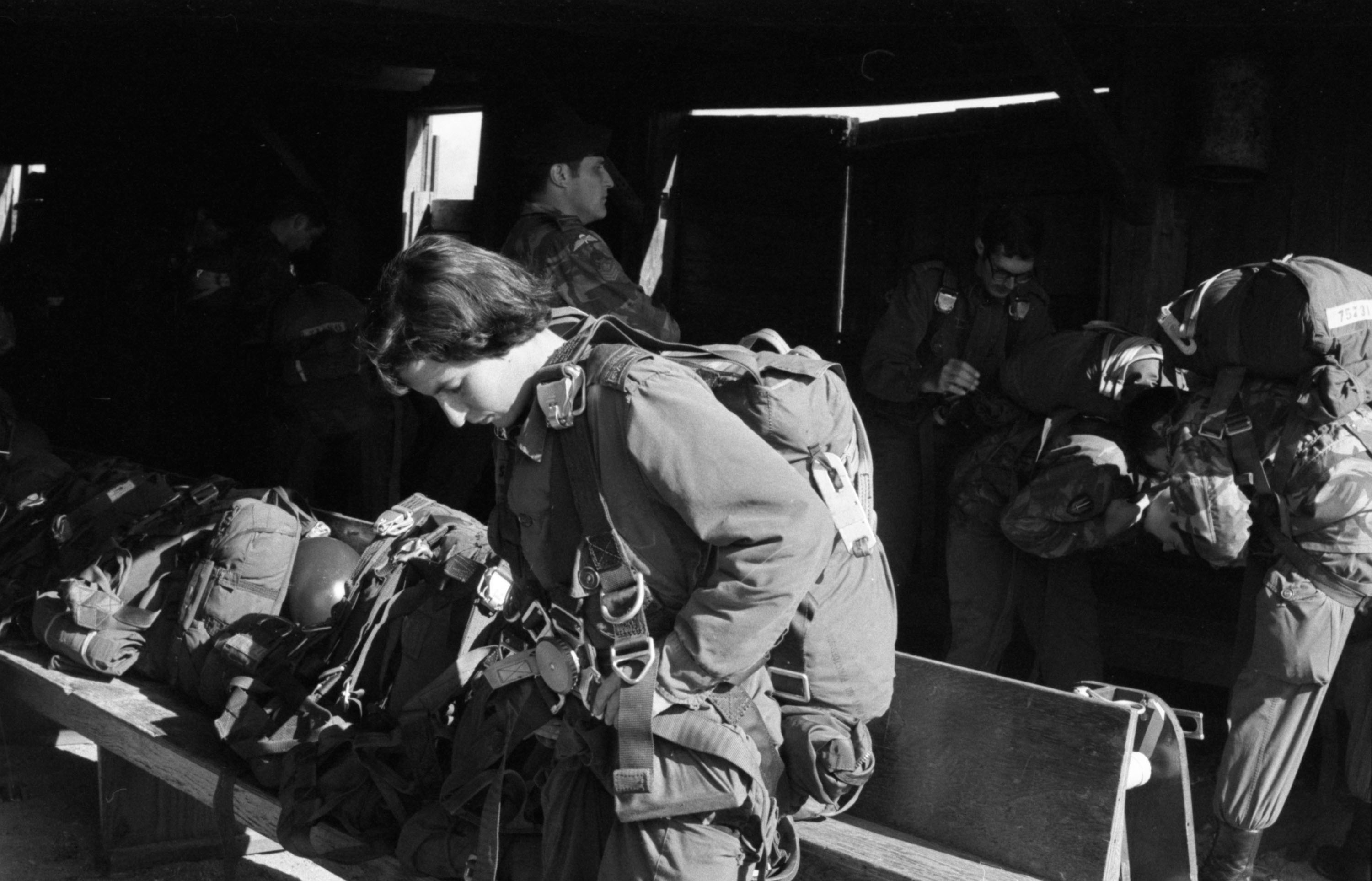

For a night drop, the Battalion turns up at the “nose dock” (a hangar big enough for the entire front end of a Hercules except for the tail), early in the evening, with their small-arms (rifles, Karl Gustav and M-72 anti-tank weapons etc.), rucksacks and equipment ready to go. The order to get dressed is given, and the buddy system is applied as each paratrooper dons his parachutes and mounts his rucksack and any special equipment he may have to carry (extra mortar rounds, fuel, water, extra ammunition, radios, snowshoes and so on). Each jumper is then checked by a rigger, who examines the paratrooper’s main and reserve parachutes, rigs his static-line and after his inspection is complete, declares him ready to go (usually with a solid slap on the butt of the jumper’s parachute harness and container). When all are dressed, the senior jumpmaster (JM) or his deputy will then order, “Listen up for the JM briefing.” He will then brief the sticks of men who have been prepared for their specific “chalk” load on the jump procedures appropriate to the type of aircraft they are using, such as the Hercules or Buffalo transport aircrat or Griffon helicopters, and on where, when and how the drop will take place, at what altitude, the likely wind conditions and potential hazards they may encounter on the drop zone, and a reminder of emergency procedures in the event of a hang-up (being towed behind the aircraft if the static-line doesn’t separate etc.) The JM will then complete his orders by stating, “You have now been manifested and will jump in accordance with these orders and instructions,” at which point all will shout “HuaaH!” in response.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 5056416)

Lt Savard dressing for a static line jump, with Sgt Ralph Goebel in the background, likely at Namao, Alberta, 1978.

For a 12-plane drop, we have used fourteen Lockheed C-130 Hercules aircraft standing by with the props churning (two were back-up aircraft in case any broke down or otherwise become unserviceable). The order to embark is given, and you may imagine the picture of long lines of double rows of men marching out across the tarmac runway to board twelve separate aircraft. (Actually, waddling would be a better description than marching, as they are heavily weighed down with parachute equipment and their rucksacks mounted in front). The Pathfinder reconnaissance team will have flown out earlier, as they will be jumping in freefall from a higher altitude (about 10,000’ to 12,000’), and their rucksacks are mounted behind them. Their primary job is to mark the drop zone and to secure it with their weapons.

(Author Photo)

Military Free Fall Pathfinders exit a Lockheed CC-130 Hercules.

(Author Photo)

Pathfinder in freefall – note the MFP jumper’s rucksack is mounted behind him, static line jumpers carry it mounted in front.

Once onboard the aircraft, all jumpers put their seatbelts on, white lights are extinguished and the aircraft’s interior red lights are turned on to preserve night vision. All the aircraft taxi out in a long convoy-like line, and take off in “trail” formation. To prevent one long line of continuous targets presenting itself over the drop zone, the entire group of Hercules transports is split into four separate flights of three, which will approach the dropzone from different directions each flying in a “finger-three” V formation.

Each separate flight of Hercules will proceed to fly cross-country at a very low level until just before the run-in for the drop, and then ramp-up to the pre-determined jump altitude (1,000 feet to 1,200 feet in training, 650 feet to 700 feet over hostile terrain).

About ten minutes before the drop takes place, the jumpmaster (JM) on board each separate aircraft will issue the first of a sequence of commands, beginning with the attention-getting words, “Look this way!” Each paratrooper is anticipating this command and is particularly “focused” at this point, and on all succeeding commands given by the JM, which are shouted back, word for word, to ensure no one has missed hearing them. The next command shouted out by the JM is, “Seat belts off!” Every paratrooper reacts and complies in a coordinated and concerted action, and when ready, turns in his seat to face the JM again.

The next command is, “Stand Up!” at which point each jumper stands up and then removes his static line snap from where it had been stowed by the Rigger in an elastic band on his reserve and then he takes one step towards the heavy steel static line cable strung overhead, holds the open snap up to the cable and prepares to hook on. On the command, “Hook Up!”, the jumper snaps his static line onto the overhead cable which runs the length of the aircraft’s interior, and slides it to the rear for the person behind him to double check, at which point the JM shouts “Check Static Line!” Each jumper examines the snap and static line of the person in front of him to see that it is secure, then he traces a path with his hand down the yellow nylon cord to the back of the parachute on the man in front and tightens up the slack in the elastic bands holding the remaining static line stows in place. The second last and last men in the line make a half turn so they can check each other.

The next command is, “Check your equipment!” This is when a jumper takes the opportunity to move his testicles and other private parts out from underneath the leg straps and double checks every snap and strap including his helmet and the equipment that he is wearing. The JM then double checks the snaps and kit of every single man in the line, then returns to his position near the exit door and shouts, “Sound off for equipment check!” Starting with the last man, each man shouts out in succession, “1 OK, 2 OK” and so on, with the last man standing closest to the exit door pointing to the JM and shouting, “All OK,” when all have sounded off. About this time the red warning light over the jump door comes on. The JM and his deputy slide the doors up on each side of the Hercules, and stamp on the jump steps to ensure they are secure for “double-door exit.” In some cases the rear ramp may be lowered instead.

By now the three Hercules in each formation are in the process of moving from a line astern or “trail” formation into the finger-three formation. It is a spectacular sight if your are number one on the ramp of the lead Hercules watching the other two aircraft lined up behind your aircraft as they slide over to the left and right wings parallel with your aircraft.

The JM shouts, “Stand By!” and all jumpers step forward, sliding their static lines with them. When the green light flashes on, the JM shouts “GO!” At this moment each and every paratrooper immediately steps forward in a one-two movement (known as the mambo step), and as he reaches the door or the end of the ramp, he throws his static line forward, stamps down hard on the jump step to get a good “launch,” and exits smartly out the door, head down, feet together, hands on each side of his reserve, ready for the worst, hoping for the best, sounding out the count, “1,000, 2,000, 3,000, 4,000, 5,000, check canopy!”

The heat and the prop wash from four churning propellers hits the jumper just as he drops below the aircraft and the big round green T-10 parachute seems to explode off his back (many times harder than the gentle openings one experiences from a helicopter jump). The tightened harness straps keep him from being squeezed the wrong way, and after his count he will immediately look up to check for a properly open canopy. It is extremely rare that it does not open properly, primarily due to the Canadian invention of netting that runs around the skirt of the canopy which prevents partial malfunctions. The jumper then quickly grabs his rear risers and begins looking sharply around him all directions to watch for other jumpers and to avoid a canopy collision. If necessary, he will slip in the opposite direction by pulling down on the pair of suspension risers in the direction he needs to steer. If it is as dark as the inside of a monkey’s nether end, he will look, listen and feel for the wind on his face to get an idea of which way it is taking him. If it is a moonlit night, he will watch for the wind blowing along the grass or snow which looks like waves of fur fluttering along the back of a woolly bear, to get an idea of where to land and what obstacles to avoid.

About 300 above the ground, each jumper lowers his rucksack by pulling a special release tab, which lets it drop to hang about 15 feet below him. It will swing somewhat, but if it is really dark, he will feel it thump first and have some warning of when he needs to prepare to make contact with the ground. He keeps his feet and knees together and his elbows in tight as he prepares to hit and roll, arcing his body in the direction he is swinging and hopefully not landing too hard or on anything sharp.

Once the jumper has completed his “parachute landing fall” (PLF) on the ground he has to quickly deflate his chute to keep from being dragged by pulling on one of the risers to draw it towards himself. He then quickly undoes his reserve, punches his quick release system to get out of the harness, and very quickly extricates his weapon. If it is his rifle, he may have to remove it from his snowshoes, and if it is a Sterling Sub-machinegun (SMG), clear it from under his reserve. To reduce his outline as a potential target, the paratrooper keeps low to the ground as he gathers the chute and stuffs it into the built-in bag it comes with, then dons his rucksack and he prepares to move off the Drop Zone to meet the rest of his section at a pre-determined rendezvous (RV) point. (In training jumps you bring all your kit with you to the RV point, in exercises you drop the parachute bags at a collection point and then get on with the exercise). At all times he must keep a watchful eye out for other jumpers and their equipment as they descend above him from the following waves so they don’t land on him, particularly if they are dropping a platform with one of the Regiment’s Airborne Artillery Battery guns, or an M113 C & R Lynx armoured reconnaissance vehicle, an M113 armoured personnel carrier (APC), or a TOW missile mounted on a jeep.

Each Commando team is watching for the pathfinder’s markers. A soldier may have to wave a small blue, green or red light on a pole for a few seconds every few minutes to guide each group into their RV point if it is really dark. If there is moonlight, the jumper can use his compass to get to an observable RV. As soon the majority of each assault team is in place, they move on to the objective. Time is of the essence, and it is very hard to recover when it has been lost. In a hostage-freeing scenario, the terrorists are hit according to the plan. Sometimes changes have to be made on the spot, and paratroopers have a ready instinct for an alternate but workable plan when necessary. In this exercise, the enemy force was taken out or neutralized, the hostages were freed and collected along with the wounded, and all injured were brought to a pre-planned collection point.

If it is a long-range operation, the paratroopers walk out. If it is a combat extraction operation, all assemble at pre-determined points on a designated runway. Each aircraft will roar in to land, and taxi to the end of the runway lowering its ramp as it reaches the turn-around point to prepare for take-off. In the few seconds the non-stop turn around takes place, each stick will re-board an incoming aircraft. When the Hercules has turned 180° and is facing the opposite end of the runway, the ramp is raised whether all are on board or not, and the aircraft takes off.

Each empty aircraft will take a turn coming in until all on the ground have been collected. It gets trickier loading the wounded with all due care and assistance, and no dead are left behind, so the body bags have to be carried on board as well as the extra people including hostages and prisoners. On this exercise, which took place at CFB Borden, Ontario, more than 200 additional people were flown back, while a number on the ground made their way to vehicles hidden off-site. In spite of the hasty activity, no one wants to be left behind to hike 25 kilometres north to an alternate ground collection point, and in this last mission, everyone and everything except those role-playing the enemy force was onboard the tenth aircraft to land, leaving the last two pilots severely annoyed because they still had to practice their rapid extraction skills minus live bodies on the ground to load.

While airborne on the flight back, medics were very busy working to plant IV s, treat the wounded and manage triage. Everyone helped out. Within an hour or two, all were back on the ramp at CFB Petawawa, and very shortly afterwards slid into a debriefing room to go over what has been collected and to discuss the lessons learned during the operation. We will have gotten in, done the job and gotten out, as close to the schedule and plan as possible. We will also have proven once again, the Airborne gets the job done.

Ex Coelis!

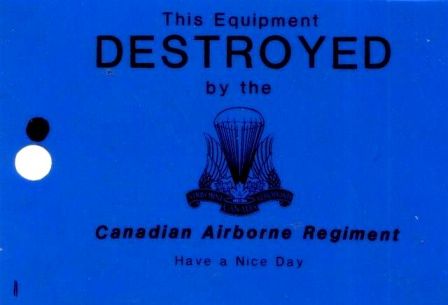

Equipment destroyed tag provided by the Airborne Intelligence Section for use by the Canadian Airborne Regiment on exercise.

[1] The Author earned his military jump wings in 1975 at CFB Edmonton, Alberta, and later served as a member of the Canadian Forces Parachute Team (CFPT), the SkyHawks from 1977 to 1979. From 1986 to 1989 he served as the Regimental Intelligence Officer for the Canadian Airborne Regiment (CAR) within the First Special Service Force (FSSF) based at CFB Petawawa, Ontario, when the training exercise described here took place. He continued to serve as an active military parachutist until his retirement as a Major at 5 Canadian Division Support Base Gagetown, New Brunswick, in August 2011. He has been the Honorary Lieutenant-Colonel for 3 Intelligence Company, Halifax from Feb 2015 to Feb 2018.

The CAR motto is “Ex Coelis” (from the skies).

The Airborne Forces Monument, located at the entrance to the Canadian Forces Base Petawawa, Ontario, was dedicated on 28 August 1988. It was constructed in memory of the Canadian Airborne Forces, including the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, The Canada/USA Special Service Force, and Defence of Canada Parachute Units, on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Canadian Airborne Regiment.

The Canadian Airborne Regiment commissioned this monument to mark its 20th anniversary and to honour all past and present Canadian operational parachute units. Colonel Andre D. Gauthier (CF Ret’d) of Orleans, Ontario, designed and sculpted this 8 foot high bronze statue. The artist named the sculpture “INTO ACTION” and it depicts a contemporary Paratrooper in winter gear who has just landed on a frozen lake drop zone, shed his parachute harness (seen at his feet), picked up his rifle and is heading “into action”. The dedication ceremony involved an Honour Guard from the Canadian Airborne Regiment, a Flag Party of Canadian and USA Veterans, a Canadian Forces band, and numerous guests and veterans of Airborne Forces. Although the Canadian Airborne Regiment was disbanded in 1996, the Airborne role lives on in three Light Infantry battalions (3 PPCLI, 3 RCR and 3 R22eR) which each have a Parachute Company; the monument remains under the care of the Parachute Company of 3 RCR in Petawawa.

Airborne Coin

In the pocket of every member of the Airborne Regiment, if you are lucky enough to be allowed to see it, you will find his most prized possession, his coin. The Airborne coin is not something that is easily obtained, it must be earned. An Airborne soldier must carry his coin with him at all times. At any time, another soldier can “coin” you by producing their coin. If you can’t produce your coin, you must buy a round of drinks for every soldier who produces a coin in response to the challenge. If however, everyone produces a coin, it falls on the challenger to buy the round.

Flag of the Canadian Airborne Regiment, Infantry School. 5 Canadian Division Support Base Gagetown, New Brunswick.