Aida de Acosta

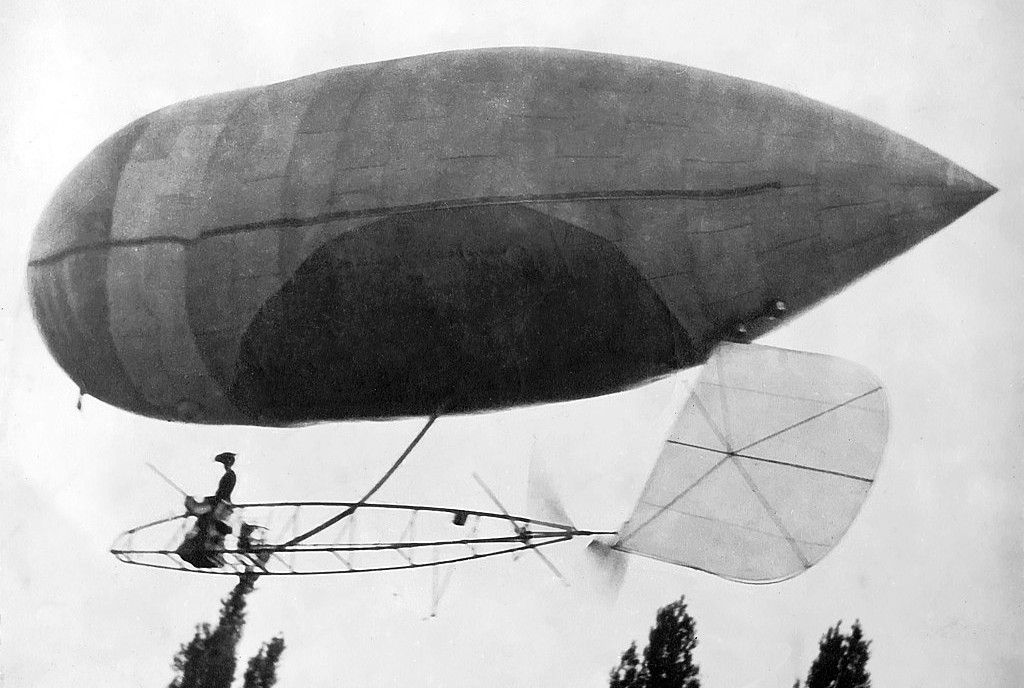

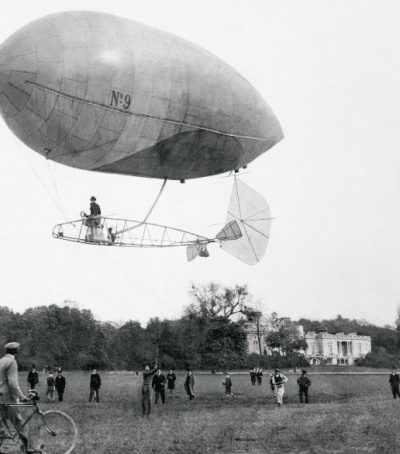

Aida D’Acosta Breckinridge piloted Alberto Santos-Dumont’s airship N° 9, La Baladeuse in 1903.

On 27 June 1903, in Paris, when Acosta was nineteen, Brazilian pioneer aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont showed her how to operate his personal dirigible, “No. 9.” Santos-Dumont was the toast of Paris at the time, flying his dirigible downtown to his favorite restaurant and parking it on the street while he had dinner. Acosta flew Santos-Dumont’s aircraft solo from Paris to Château de Bagatelle while Santos-Dumont rode his bicycle along below, waving his arms and shouting advice.[6]Acosta later recalled that upon her first landing, Santos-Dumont asked her how she had fared. “It is very nice, M. Santos-Dumont,” she replied. “Mademoiselle,” he cried, “vous êtes la première aero-chauffeuse du monde!” (“Miss, you are the first woman aero-driver in the world!”). She was in fact the first woman to pilot any kind of motorized aircraft, nearly six months before the Wright brothers first flew in a heavier-than-air powered aircraft. The first flight ended in the polo field at Bagatelle at the northern end of the Bois de Boulogne, during a match between the American team and the British team. Spectators assisted her from the basket. After watching some polo with Santos-Dumont, Acosta climbed back into the basket and flew the machine back to Neuilly St. James, the entire trip lasting one and a half hours.

Aida de Acosta made history in 1903 as the first woman to pilot a powered aircraft, flying the airship *Baladeuse*. At just 19 years old, she was inspired to take to the skies after witnessing the flight of the *Giffard* airship and the burgeoning field of aviation. With a passion for adventure and a desire to prove that women could excel in this male-dominated arena, she sought out the guidance of her mentor, the renowned aeronaut Auguste and his brother, Alfred Giffard. They provided her with the necessary training and support, ultimately allowing her to pilot the *Baladeuse* during a flight over Paris.

On July 2, 1903, Aida ascended in the *Baladeuse*, a small dirigible equipped with a lightweight engine. Her journey lasted approximately 30 minutes, during which she showcased her remarkable skills and courage as she navigated the airship through the skies. The flight was a significant milestone not only for Aida but also for women’s roles in aviation, challenging societal norms and perceptions of women’s capabilities. Her success garnered attention, with newspaper articles highlighting her achievement and inspiring other women to pursue their ambitions in aviation and other fields.

Despite her groundbreaking accomplishment, Aida de Acosta’s name faded from the public consciousness as aviation evolved rapidly in the following decades. Nonetheless, her pioneering spirit and determination paved the way for future generations of female aviators. In recognition of her contributions to aviation, historians and enthusiasts continue to celebrate Aida’s legacy, emphasizing the importance of her role in shaping the narrative of women’s participation in aviation history.

(Bain News Service Photo)

Mrs. Oren Root (nee Aida De Costa), 1910. Aida de Acosta Root Breckinridge (July 28, 1884 – May 26, 1962) was an American socialite and aviator. She was the first woman to fly a powered aircraft solo. In 1903, while in Paris with her mother, she caught her first glimpse of dirigibles. She then proceeded to take only three flight lessons, before taking to the sky by herself. Later in life, after losing sight in one eye to glaucoma, she became an advocate for improved eye care and was executive director of the first eye bank in America. (Wikipedia)

On 27 June 1903, in Paris, when Acosta was nineteen, Brazilian pioneer aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont showed her how to operate his personal dirigible, “No. 9.” Santos-Dumont was the toast of Paris at the time, flying his dirigible downtown to his favorite restaurant and parking it on the street while he had dinner. Acosta flew Santos-Dumont’s aircraft solo from Paris to Château de Bagatelle while Santos-Dumont rode his bicycle along below, waving his arms and shouting advice.

Acosta later recalled that upon her first landing, Santos-Dumont asked her how she had fared. “It is very nice, M. Santos-Dumont,” she replied. “Mademoiselle,” he cried, “vous êtes la première aero-chauffeuse du monde!” (“Miss, you are the first woman aero-driver in the world!”). She was in fact the first woman to pilot any kind of motorized aircraft, nearly six months before the Wright brothers first flew in a heavier-than-air powered aircraft.

The first flight ended in the polo field at Bagatelle at the northern end of the Bois de Boulogne, during a match between the American team and the British team. Spectators assisted her from the basket. After watching some polo with Santos-Dumont, Acosta climbed back into the basket and flew the machine back to Neuilly St. James, the entire trip lasting one and a half hours. (Wikipedia)

Alberto Santos-Dumont captured the imagination of the world with his balloons and motorized airships. In Paris, he was a common sight flying low over the rooftops and through the streets where he would tether his dirigible to a lamp post near his favorite cafe and order a drink. In 1901, he became one Paris’s most loved celebrities when he won the 100,000-franc Deutsch Prize for an 11.3-km (7-mile) flight with his airship No. 6 from the suburb of St. Cloud to the Eiffel Tower and back in less than half an hour. The victorious aeronaut then presented one-quarter of the purse to his crew and the rest to the poor people of Paris.

Aida was just 19 when she met Alberto in Paris. Santos-Dumont wrote that Aida de Acosta “was a very beautiful young Cuban lady, well known in New York society…having visited my station with her friends on several occasions, (she) confessed an extraordinary desire to navigate the air-ship.”

Aida’s training included learning the basics of steering the rudder with a lever for the propellers, shifting ballast as needed, and the all-important way to get airborne by dropping weights. It only took her 3 lessons before Santos-Dumont deemed Aida ready for her flight. Santos-Dumont decided to use his handkerchief to help relay signals to Aida while he followed along under the flying machine on his bicycle. “If I wave it with my right hand, you will turn toward the right, and so, on the left. If I wave it around in circles, you will make the motor go as fast as it can.”

And he added the most valuable safety measure – a length of rope tied to her wrist. She was to pull this rip cord attached to a panel on the gas bag if she should go too high or lose control. This would allow the machine to come down quickly. If she fainted, the rip cord would serve the same purpose. She was ready to fly!

29 June 1903 was a beautiful and practically windless day in Paris. Many were outside enjoying the day and especially fans of the American and British polo teams who were playing that day in a field at Bois de Boulogne. Santos-Dumont and Aida decided this was the perfect day for a flight. They left the hangar with Aida in the basket and Santos-Dumont riding below on his bicycle giving directions onward toward the polo field.

Aida must have been enchanted as the rooftops of Paris glided by while she fearlessly piloted the Zeppelin alone. All too soon she arrived at the polo field and gently set the aircraft down with help from those on the ground pulling the dragging guide rope. Santos-Dumont met her with a wild grin and asked how she’d fared. “It is very nice, Monsieur Santos-Dumont,” Aida said.

“Mademoiselle,” he cried, “vous êtes la première aero-chauffeuse du monde!” (You are the first woman aero-driver in the world!)

They watched some of the polo match together until it was time for her to get back in the basket alone and head back to the hangar. The entire trip took about one and 1/2 hours. Aida de Acosta flew Santos-Dumont’s aircraft alone from Paris to Château de Bagatelle and landed in the polo field. This was six months before the Wright Brothers’ first flight. Thus she became the first woman to pilot a motorized aircraft solo.

The press who were covering the international polo match immediately wanted to know more about the young lady who piloted the aircraft. Unfortunately for Aida, the excitement she must have felt was very quickly squashed when her mother heard of the adventure and the interest of the press. Aida was a girl of 19 who lived in the Victorian age where notoriety in the newspapers was not something a lady of social standing would seek in any form – except for her birth, marriage, and death.

Aida’s mother immediately went to Santos-Dumont and asked that her daughter’s name not be mentioned to the press or in any of memoirs, as this would cause a great scandal in the family. To prevent any further possibility of the family being dishonored, she quickly packed up and took Aida back to New York. Alberto Santos-Dumont agreed to do as she asked and faithfully kept his word. He only mentioned Aida by description in his book, My Airships, and never gave her name.

It wasn’t until almost 30 years later that Aida’s secret was revealed. She was hosting a dinner party in 1932 when a young naval officer spoke of his dream to fly a dirigible one day. Aida smiled and said, “I’ve flown dirigibles myself; they are a lot of fun.”

It was the first time she had ever revealed she was the girl who flew solo in 1903 Paris in the No. 9 La Baladeuse owned by the famous Alberto Santos-Dumont. There were a few photos of her taken that day, but until that moment no one knew who the mysterious woman was who became the first female to fly solo in a motorized flying machine. Aida de Acosta – socialite, philanthropist, and the first woman pilot died in Bedford, New York on 26 May 1962 at the age of 77. (Lisa Chavez)