Formed in 1962, the coast guard is tasked with marine search and rescue (SAR), communication, navigation, and transportation issues in Canadian waters, such as navigation aids and icebreaking, marine pollution response, and support for other Canadian government initiatives. The coast guard operates 119 vessels of varying sizes and 23 helicopters, along with a variety of smaller craft. The CCG is headquartered in Ottawa, Ontario, and is a special operating agency within Fisheries and Oceans Canada (Department of Fisheries and Oceans).

The CCG works to ensure the safety of mariners in Canadian waters and protect Canada’s marine environment. The CCG supports Canada’s economic growth through the safe and efficient movement of maritime trade. The CCG helps to ensure Canada’s sovereignty and security through its presence in Canadian waters.

(CCG Photo)

CCGS Donjek Glacier.

As part of its fleet renewal plan, the Canadian Coast Guard is acquiring two Arctic and Offshore Patrol Ships (AOPS) to replace two of the five existing Offshore Patrol Vessels. The new AOPS, named the CCGS Donjek Glacier and CCGS Sermilik Glacier, will support offshore international fisheries surveillance and Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization patrols, and offshore search and rescue on Canada’s east coast and in the low Arctic.The AOPS are versatile and modern ships that will allow greater flexibility and adaptability for the Canadian Coast Guard’s operations, including icebreaking, science research, humanitarian assistance, and aids to navigation.The AOPS are designed to be able to support icebreaking operations in the low Arctic during the summer and on the East Coast during the winter. They are also outfitted with a medical cabin and shipping container accommodation, which allow the vessels to provide humanitarian assistance and support resupply operations to communities when needed. Equipped with a robust crane and an A-frame on the stern of the ship, to lower packages from the working deck to the water, the AOPS will be capable of supporting aid to navigation operations and science research. (CCG)

The AOPS are highly capable and versatile ships, able to perform as an at-sea operations centre. The AOPS can operate beyond 120 nautical miles from shore, including outside the Exclusive Economic Zone, have a top speed of 17 knots, and can stay at sea for up to 48 days.

Other main specifications of the ships include: 103 metres long19 metres wideapproximately 6,677 metric tonnes of displacementcan accommodate a crew of 31 members with berths for 57 in totalavailable command and control spaces20-tonne crane in the back of the vessel to support aids to navigation operationsan A-frame designed to support science missionsshipping container capability for resupply missionsThe new AOPS have a helicopter pad and hangar that will allow the ships to accommodate both light (Bell 429) and medium lift (Bell 412 EPI) Canadian Coast Guard helicopters, as well as National Defence’s Cyclone helicopters. (CCG)

(Corporal David Veldman – Canadian Armed Forces Photo)

CCGS Jacques Cartier.

With 123 vessels, the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) is the federal government’s largest maritime organization in terms of hull numbers. Unlike the coast guards of many other countries, its members are responsible for ensuring the safe use of Canadian waters by seafarers rather than enforcing laws through the threat and use of low-level force. It is predominantly a safety, rather than security (narrowly defined), organization. CCG members do not have law enforcement authority and cannot carry out arrests. For these functions, non-CCG members such as fisheries officers (DFO) or Royal Canadian Mounted Police officers are required. Nonetheless, the CCG provides maritime monitoring services while CCG vessels provide the floating platforms necessary to carry those officials as they conduct their missions at sea. Perhaps the most significant of these missions in the coming decades will be offshore fisheries enforcement. As demand for saltwater protein by populous coastal states like China increases over the coming years and their local waters are depleted, there will be more distant-water fishing vessels seeking out new sources of seafood. This has already involved the use of lethal force by other coastal states’ coast guards and navies around the world as they have tried to halt IUU fishing in recent years, notably off South America’s coasts.

Thus, although much popular attention is focused on the CCG’s icebreakers and their role in Canadian Arctic sovereignty, an oft-overlooked area is the CCG’s role in supporting Canada’s control of its fisheries at the edges of its 200-nautical-mile (NM) exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Canada also has a role in protecting fisheries beyond the 200-NM EEZ, thanks to its membership in the North Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO), which sets out quotas and other limits on fishing in the high seas (beyond 200 NM) off Canada’s Atlantic coast. Although Canadian offshore fisheries enforcement actions have not been in the spotlight in recent years, they were a regular feature of the DFO’s fisheries patrol fleet prior to their 1995-1997 amalgamation with the CCG.

Thanks in part to the regular enforcement actions that culminated in the mid-1990s turbot war with Spain and the resultant long-term resolution under the United Nations Straddling Stocks Agreement, the CCG has not had to threaten the use of force at the outer edges of Canada’s EEZ. Canada’s ability to assert its position and ensure it was accepted by the international community was made possible not only by the use of civilian DFO patrol forces, but also by the deployment of the Canadian navy’s warfighting forces as platforms for DFO fisheries officers under fisheries patrols (FISHPATs). In the 1980s and early 1990s, the Canadian Atlantic naval fleet had both the numbers and limited operational requirements to allow it to participate in increasing numbers of FISHPATs following the establishment of the 200-NM zone. These included using Iroquois-class destroyers to chase down trawlers in the mid-Atlantic which had kidnapped fisheries officers and deploying Oberon-class submarines to surveil and deter illegal fishing on the Georges Bank maritime boundary with the United States.

The use of Canadian navy platforms to fulfil increased FISHPAT sailing hours was possible during the early ’90s due to the end of the Cold War and the limited overseas presence requirements of the Canadian navy (with the exception of Desert Storm). In the subsequent decades, however, Canada’s increased foreign policy interests have led to greater use of its naval forces on regular overseas deployments even as its number of ships dwindled due to aging hulls that went unreplaced. This has reduced their availability for domestic support missions such as offshore FISHPATS. Thankfully, there has been a limited need for such domestic operations due to previously settled institutional solutions to Canada’s offshore fisheries disputes. However, while solutions like NAFO have been effective, they only apply to fishing fleets belonging to the institution’s members. This means the fleets of other countries like China are not under the same jurisdiction and control, requiring direct Canadian enforcement presence and potential force should such fleets appear in and around Canada’s EEZ.

Canada’s ability to conduct offshore FISHPATs is limited today. While both the Royal Canadian Navy’s Halifax-class frigate fleet and Kingston-class coastal defence vessels can be employed for FISHPATs, recent years have seen only the latter employed in such a capacity, possibly due to the former’s globe-ranging deployments.The new Harry DeWolf-class Arctic and offshore patrol vessels are technically ideal for this task given their long endurance, active fin stabilizers to deal with heavy seas and extra accommodations for fisheries officers, but their missions in the Arctic and the Caribbean may limit their availability for offshore FISHPATs on the east and west coasts. Future overseas tasks will also call the RCN’s AOPVs away from Canadian shores, further limiting such availability. With all these commitments, it is uncertain whether the RCN can fulfil its traditional platform role in supporting fisheries officers in the event of an intensified fisheries patrol effort.

Thus, it is necessary to re-examine the offshore patrol role of Canada’s civilian fleet. As climate change makes southern waters more inhospitable to local fisheries, they may migrate northwards into waters with temperatures more suitable for their survival.11 Such waters may include those within Canada’s EEZ or NAFO’s areas of authority. Current measures for controlling, patrolling and enforcing fisheries conservation in areas of Canadian jurisdiction may no longer suffice. Increased presence at sea with an ability to surveil, interdict, halt and arrest violators will likely be required in the coming decades. The CCG will be the seagoing agency in this regard. (Timothy Choi, CGAI Fellow)

(Jordanroderick Photo)

CCGS Tanu is a fisheries patrol vessel in service with the Canadian Coast Guard. The ship was constructed in 1968 by Yarrows at their yard in Esquimalt, British Columbia and entered service the same year. Home ported at Patricia Bay, British Columbia, the ship is primarily used to carry out fisheries patrols and search and rescue missions along Canada’s Pacific coast.

Tanu was the third of three vessels designed for fisheries patrol use on Canada’s Pacific coast. Tanu had two near-sister ships, CCGS Cape Freels and CCGS Chebucto all designed for fisheries patrols but differed slightly in layout.[1] Tanu has a full load displacement of 925 long tons (940 t), a gross tonnage (GT) of 753 and net tonnage (NT) of 203. Tanu is 52.1 metres (170 ft 11 in) long with a beam of 9.9 metres (32 ft 6 in) and a draught of 3.5 metres (11 ft 6 in).

The ship is powered by two Fairbanks Morse-38D8 geared diesel engines driving one controllable pitch propeller and bow and stern thrusters.. The machinery is rated at 1,968 kilowatts (2,639 hp) and gives the vessel a maximum speed of 13.5 knots (25.0 km/h; 15.5 mph). Tanu has capacity for 236.4 m3 (52,000 imp gal) of diesel fuel which gives the ship a range of 5,000 nautical miles (9,300 km; 5,800 mi) at 11 knots (20 km/h; 13 mph) and an endurance of 22 days. The vessel is also equipped with three Caterpillar C9 generators and one Perkins 2430 emergency generator. Tanu has a complement of 15 composed of 6 officers and 9 crew, with berths for an additional 16. The vessel can be equipped with two 12.7 mm machine guns. (Wikipedia)

(CCG Photo)

CCGS Sir Wilfred Grenfell.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4951182)

HMCS Labrador in ice proceeding through Bellot Strait, 24 August 1957. CCGS Labrador was a Wind-class icebreaker. First commissioned on 8 July 1954 as HMCS Labrador (AW 50) in the (RCN), Captain O.C.S. “Long Robbie” Robertson, GM, RCN, in command. She was transferred to the Department of Transport (DOT) on 22 November 1957, and re-designated Canadian Government Ship (CGS) Labrador. She was among the DOT fleet assigned to the nascent Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) when that organization was formed in 1962, and further re-designated CCGS Labrador. Her career marked the beginning of the CCG’s icebreaker operations which continue to this day. She extensively charted and documented the then-poorly-known Canadian Arctic, and as HMCS Labrador was the first ship to circumnavigave North American in a single voyage. The ship was taken out of service in 1987 and broken up for scrap in 1989.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4950065)

HMCS Labrador, 1961.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4950137)

Canadian Coast Guard Ship d’Iberville, 1957.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3199579)

Canadian Coast Guard Ship d’Iberville, August 1953.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4374238)

Canadian Coast Guard Ship Sir John A. MacDonald off Burnett Inlet, 12 August 1963.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4952604)

CCG Icebreaker, 1957.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3223594)

Hudson Strait Expedition, Cletrac tractor going ashore from CGS Stanley at Base ‘B’, August 1927.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3278249)

CCGS Mikula.

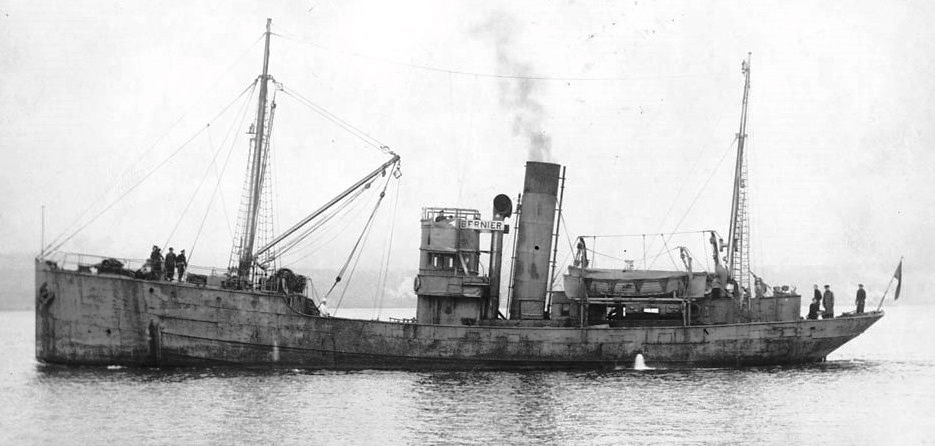

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4374224)

Canadian Coast Guard Ship J.E. Bernier, operated in the lower St. Lawrence River and the Gulf of the St. Lawrence. It was christened 28 April 1967.

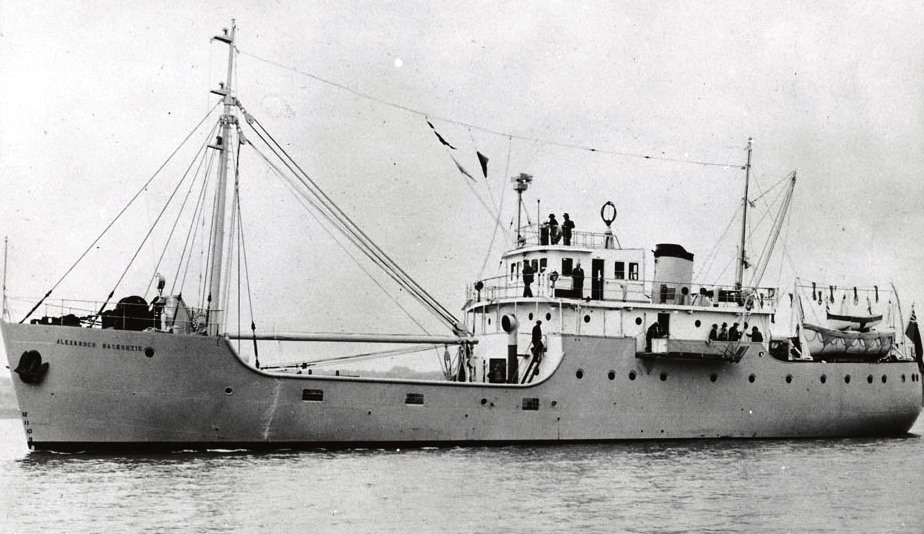

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4374223)

Coast Guard Ship Alexander Mackenzie – Lighthouse Supply and Buoy Vessel.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3724036)

Coast Guard Ship Canada

CCG Aircraft

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4374221)

Canadian Coast Guard helicopter on ice reconnaissance over St. Lawrence near Quebec City.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4374237)

Escorting charter vessel Eskimo, Canada Steamship Lines, and Canadian Coast Guard Narwhal out from Brevoort Island, 2 August 1963.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3613664)

CCG Sikorsky Sea King helicopter, above the Triple Island light station near Prince Rupert, British Columbia, 31 July 1967.

(Ken Fielding Photo)

de Havilland Twin Otter, Reg. No. C-FCSU, 22 September 2010.

(John Davies Photo)

de Havilland Canada DHC-8-102 Dash 8, Canadian Coast Guard – Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 26 October 2001.

(Dennis Jarvis Photo)

CCG Bell 206L LongRanger, Reg. No. C-GCHR, 6 March 2008.

(Cephas Photo)

CCG Messerschmitt-Bolkow-Blohm (BO-105-CBS) helicopter, Reg. No. C-GCHR, 8 March 2011.

(Letartean Photo)

CCGS Cap Aupaluk assisting the RCAF in a training exercise, 30 May 2012.