Royal Canadian Artillery in North West Europe, 1944-1945

1st Canadian Army Group, Royal Canadian Artillery, (1st Cdn AGRA)

11th Army Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

1st Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

2nd Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

5th Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

56th Heavy Regiment, Royal Artillery (from Mar 1945)

2nd Army Group, Royal Canadian Artillery, (2nd Cdn AGRA)

19th Canadian Army Field Regiment

3rd Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

4th Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

7th Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

10th Medium Regiment, Royal Artillery

15th Medium Regiment, Royal Artillery, (disbanded December 1944)

1st Heavy Regiment, Royal Artillery

2nd Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment (Mobile)

1st Rocket Battery

1st Radar Battery

1st Canadian Infantry Division

1st Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Horse Artillery

2nd Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

3rd Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

1st Anti-Tank Regiment

2nd Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment

2nd Canadian Infantry Division

4th Field Regiment

5th Field Regiment

6th Field Regiment

2nd Anti-Tank Regiment

3rd Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment

3rd Canadian Infantry Division

12th Field Regiment

13th Field Regiment

14th Field Regiment

3rd Anti-Tank Regiment

4th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment

4th Canadian (Armoured) Division

15th Field Regiment

23rd Field Regiment (Self-Propelled)

5th Anti-Tank Regiment

8th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment

5th Canadian (Armoured) Division

17th Field Regiment

8th Field Regiment (Self-Propelled)

4th Anti-Tank Regiment

5th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment

I Canadian Corps Troops

7th Anti-Tank Regiment

1st Survey Regiment

II Canadian Corps Troops

6th Anti-Tank Regiment

2nd Survey Regiment

6th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment

Royal Canadian Artillery in North West Europe

The First Canadian Army, which was commanded initially by General A.G.L. McNaughton then by General H.D.G. Crerar (both Gunner officers), would have two army artillery groups (AGRAs), two corps artilleries and five divisional artilleries as its primary fire support. The RCA would eventually go on to play a major part in the campaigns in Sicily, Italy and northwest Europe.

Elements of the 2nd Divisional Artillery – mainly men from 3 LAA Regt with Bren guns to provide the raiders with air defence – landed at Dieppe in 1942. In 1943, the guns of the 1st Division supported Canadian armour and infantry units through Sicily. Next, on the Italian mainland, the 1st Divisional Artillery, augmented later by 5th Divisional and 1st Corps Artillery, assisted in smashing a way through the German defenders up the long Italian peninsula until all Canadian troops were concentrated in northwest Europe in 1945.

On 6 June 1944, the Gunners accompanied the assaulting infantry of the 3rd Division, firing their self-propelled 105mm howitzers from the decks of their landing craft on the “run in” to the Normandy beaches. This would be followed by the break-out, the Falaise Gap, the drive up the Channel Coast, the push through Belgium to the Scheldt, the liberation of the Netherlands, the southeast punch through the Hochwald and the Battle of the Rhine. Numerous barrages, concentrations and ceaseless harassing bombardments were fired in support of the 1st Canadian Army in its bitter engagements with the Germans.

Developments in artillery played a large role in the Allied victory during the Second World War. While there were no revolutionary changes to artillery weapons from the First World War, there were significant evolutionary improvements in range, ammunition efficiency, maintenance and mobility of guns. These included the successful combining of the characteristics of a gun (high velocity) and howitzer (high trajectory) in the 25 Pdr and the development of self-propelled artillery. Another early innovation during the Second World War was that the Observers were no longer expected to calculate gun data for indirect fire as had been the practice throughout the First World War, but left that function to the Command Posts, providing only target locations, descriptions and orders for weight of fire as per the modern practice.

Canadians took part in the most important artillery development of the War, that is the ability of an allied commander to quickly bring down the fire of a massive concentration of guns (from division, corps or even army artillery) onto a single target in a short space of time. This required the development of reliable wireless (radio) and other communications equipment, more effective, speedy and accurate methods of gun survey and improved methods of fire control, voice procedure and fire planning. Putting this system into practice required a high level of proficiency in every troop and battery. Most concentrations fired during the war were carried out at the divisional level, where the Commander Royal Artillery (CRA) always had at his disposal the fire of two to three field regiments (48 – 72 guns). Major battles, normally controlled at the corps or army level, routinely involved the concentrated fire of 500 to 1000 guns and mortars.

A good example of how the Canadian and British Gunners were able to achieve massed, accurate fire occurred in early February 1945 during Op Veritable – the First Canadian Army’s attack from Nijmegen southeast to the Rhineland. The Army Commander, General Harry Crerar, had to make a frontal attack against three successive fortified zones, each firmly anchored on the Rhine River. These included a strong system of outposts on the western face of the Reichswald; then three miles beyond these, the northern end of the Siegfried Line; followed by the Hochwald Layback 12 miles further east. The defences included multiple lines of trench works linking strongpoints and reinforced by anti-tank ditches. Small towns and villages between the second and third zones had been extensively fortified. General Crerar’s final objective lay 40 miles from his front lines. Due to this depth, Op Veritable was planned in three stages, with enough time between each to regroup infantry and armour and to bring supporting artillery to within range of their new targets. General Crerar had 30th British Corps under command, while 1st British Corps would provide a secure anchor and deception to the South. Due to the narrow distance between the Rhine (to the north) and the Maas River (to the south), the initial assault would be made by the five divisions of 30th Corps (including 2nd Canadian Division), and as the distance between the rivers widened, 2nd Canadian Corps would join in on the left flank.

The artillery support for the operation was a major battle-winning factor. The 30th Corps Fire Plan was designed to take advantage of the 14:1 superiority in Allied artillery to blast a way for the infantry into the enemy’s defences. The Fire Plan called for:

- preliminary bombardment to prevent the enemy from interfering with the initial assault;

- complete saturation of enemy defences;

- destruction of known concrete positions;

- immediate supporting fire for the attack; and

- maximum fire of the medium regiments on the Materborn feature 12,000 yards from the start line, without their having to move forward.

The fire of seven divisional artilleries would be augmented by five AGRA’s and two anti-aircraft brigades together with units of Corps and Army level artillery, for a total of 1034 guns (not including the 17 Pdrs and 40-mm Bofors which would be used with self-propelled guns, armour, mortars and machine-guns to “Pepperpot” selected targets with harassing fire). All known enemy localities, headquarters and communications sites were targeted. An estimated six tons of shells would fall on each target. The concrete defences of the Materborn would be subjected to the fire of the 8-inch and 240-mm guns of the 3rd Super Heavy Regiment RA located in the 1st British Corps area to the South. The Fire Plan would open with the preparatory fire from 5:00 to 9:45 A.M. on D Day (8 February 1945). It would be followed by a Block Barrage planned to support the three central divisions in their advance. This barrage would commence at 9:20 for seventy minutes on the initial positions and was 500 yards deep. At H Hour (10:30 A.M.) the barrage would lift 300 yards, repeating this every twelve minutes to allow for the advancing speed of the infantry and armour over the difficult terrain.

A novel feature was introduced into the schedule for the preliminary bombardment. Between 7:30 and 7:40 a smoke screen would be fired across the front, followed by 10 minutes of complete silence. It was hoped that the enemy, assuming that the screen heralded the main assault, would engage with his artillery, thereby exposing his gun positions. At the same time, flash spotters, sound rangers and pen recorders of the locating batteries would attempt to pinpoint the enemy battery positions, allowing counter battery fire to neutralize the exposed enemy guns before H Hour.

A massive ammunition-dumping program was carried out by the 2nd Canadian Corps prior to the assault. More than half a million rounds, weighing more than 10,000 tons were dumped – 700 rounds per gun on field gun positions and 400 rounds per gun on medium positions. In addition, 120 truckloads per division of 40mm, 17 Pdr, 75mm and 12.7mm ammunition were dumped for the “Pepperpot” requirement. More than 10,000 three-inch rockets for the Land Mattress Battery were brought in. Every foot of countryside from Nijmegen to Mook and beyond on the far side of the Maas seemed to be filled with tanks, self-propelled guns and towed artillery, armoured and soft-skinned vehicles and waiting troops.

Stunned by the ferocity of the preliminary bombardment of over 500,000 rounds of various natures of ammunition and pinned down by the tremendous barrage which had expended more than 160,000 shells, the badly disorganized enemy troops offered little resistance to the assaulting infantry and armour. The effectiveness of the counter battery and counter mortar programs was seen in the almost complete lack of German shelling and mortaring. Most of the Allied casualties, which were relatively light, came from mines rather than artillery or small arms fire. Prisoners coming back through the gun positions spoke of what the artillery preparation and the barrage had done. There were reports of half the guns of a 12-gun battery having been destroyed and 32 of 36 guns having been knocked out in another locality.

Interrogators were told that the bombardment had a devastating effect upon morale, producing a feeling of complete helplessness and isolation, with no prospect of any possible reinforcement. The defenders claimed, however, that because of the well-constructed shelters, they had escaped serious casualties from the artillery fire and the “Pepperpot” in the initial assault. Those caught in the open were less fortunate. The artillery fire had also succeeded in seriously disrupting the German lines of communication and resupply.

The day’s success owed much to well-prepared gun programs, carefully sorted ammunition, much improved meteorological data and recently calibrated guns. The massive preparations had been successful in providing effective artillery support to the operation. It didn’t end there, however. The artillery would provide continuous support with barrages, screens, direct support and counter battery fire until the enemy was finally beaten three months later.

A total of 89,050 officers and men served in the Royal Canadian Artillery during the Second World War. Of these, 57,170 served in Europe, Newfoundland, the Aleutians and the Caribbean. The remainder served in Canada in home defence in field, anti-aircraft and coast units as well as in numerous schools and depots. There were also three divisional artilleries in Canada formed as part of the 6th, 7th and 8th Divisions for home defence. In 1945 another 6th Division was formed for service in the Far East Theatre, complete with its divisional artillery. It was still training in Canada and the USA when the war with Japan ended. During the War, the Regiment suffered 2,073 killed and 4,373 injured or wounded.

Total artillery available to the First Canadian Army in Europe by the end of the war included:

- 15 field artillery regiments (264 towed 25 Pdr, 48 SP 25 Pdr Sextons, 48 SP 105mm Priests);

- six medium regiments (48 5.5-in. guns, 48 4.5-in. guns);

- seven anti-tank regiments (150 towed 17 Pdr, 150 SP 17 Pdr);

- one heavy anti-aircraft (HAA) regiment (24 3.7-in. AA guns);

- seven LAA regiments (60 towed 40mm, 108 SP 40mm, 84 quad-mounted 20mm);

- 32 75mm AFV OP vehicles (in SP Field Regiments with 4th and 5th Cdn Armd Divs); and

- One rocket battery (36 Land Mattress rocket projectors).

During the war, though not part of Canada at the time, the province of Newfoundland raised two artillery regiments for service with the British Army. The 59th (Newfoundland) Heavy Regiment, RA fought in North-West Europe, while the 166th (Newfoundland) Field Regiment, RA fought in North Africa and in the Italian campaign. (RRCA Web page)

RCA Photos from the Library and Archives Canada Collection

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3208434)

Dutch children watching a Canadian artillery 25-pounder crew crossing a temporary bridge, Balkbrug, Netherlands, 11 April 1945.

No. 1 Army Group, RCA, 1st Canadian Artillery Group, Royal Artillery (1st Cdn AGRA)

11th Army Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

1st Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

The 1st Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, was one of six Canadian medium artillery regiments that served in the European Theatre during the war. Medium regiments were armed with 5.5-inch and 4.5-inch guns.

(Wikimedia Commons Photo)

5.5-inch Medium gun in Royal Artillery service.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3563841)

Gun Position Officer lining up the guns of the 1st Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (R.C.A.), with the director during a training exercise, England, August 1941.

The 1st Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, was one of six Canadian medium regiments that saw service in Britain and continental Europe in the Second World War, the others being the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th and 7th Medium Regiments. (There was no 6th Medium.)

The 1st, 2nd and 5th Mediums served in Italy, while the 3rd, 4th, and 7th were in northwest Europe. Three of these units (1st, 4th, and 7th) were each equipped with sixteen 5.5-inch (140 mm) guns, firing 100-pound shells, while the other three had 4.5-inch (110 mm) guns firing 60-pound shells.

Medium regiments were not part of the artillery component of the individual infantry or armoured divisions as were most field regiments (25-pounder guns) but were classed as “Army” troops and were available to support any formation which needed the fire of heavier guns.

2nd Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3209132)

Gunners of the 2nd Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), loading a 5.5-inch gun, Netherlands, 2 April 1945. Medium regiments were armed with 5.5-inch and 4.5-inch guns.

5th Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

On 23 February 1945 the 5th Medium learned that it was leaving Italy for North-West Europe. The regiment spent a week and a half in a camp outside of Naples (Camp Lammie) before boarding the ship, Ville D’Oran, on 12 March 1945 in Naples harbour.

On 13 March 1945, at 10:30, the 5th Medium disembarked in Marseilles and was transported to a camp outside the city. The next day, in convoy, the 5th Medium moved through the Rhone Valley of France, into Belgium. On 19 March 1945, the regiment settled in the town of Waregam. After numerous cancelled movement orders, the 5th Medium eventually received orders to move into the Netherlands, outside of Nijmegen, firing on 1 April 1945 at 23:00 on targets along the Rhine and IJssel. By 15 April 1945, the 5th Medium moved to a new position north of Valberg, remaining there until 19 April 1945 when the regiment took up its last offensive position near Barneveld.

On 26 April 1945, the 5th Medium received orders that it would not fire again, unless in retaliation. By 2 May 1945 a local truce had been declared to allow food conveys through to the Dutch citizens. On the evening of 4 May 1945, the regiment received word that the cessation of hostilities would occur on the following day and subsequently, a double issue of rum was authorized within the regiment to all personnel.

After VE Day on 8 May 1945, the regiment moved towards Hippo and eventually to Doorn. The last day of the regiment’s official existence was 30 June 1945. The final notation in the 5th Medium’s war diary ends: “This is the last entry of the war diary of the 5th Cdn. Med. Regt., RCA. FINTO — KAPUT”.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3208405)

Gunner Gerry Smith and Lance-Bombardier Bert Coughtry of the 5th Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), Otterloo, Netherlands, 5 May 1945.

The 5th Medium Regiment sailed to North-West Europe from Camp Lammie, Naples, Italy on the ship Ville D’Oran, on 12 March 1945. On 13 March 1945, at 10:30, the 5th Medium disembarked in Marseilles and was transported to a camp outside the city. The next day, in convoy, the 5th Medium moved through the Rhone Valley of France, into Belgium. On 19 March 1945, the regiment settled in the town of Waregam. After numerous cancelled movement orders, the 5th Medium eventually received orders to move into the Netherlands, outside of Nijmegen, firing on 1 April 1945 at 23:00 on targets along the Rhine and IJssel. By 15 April 1945, the 5th Medium moved to a new position north of Valberg, remaining there until 19 April 1945 when the regiment took up its last offensive position near Barneveld.

On 26 April 1945, the 5th Medium received orders that it would not fire again, unless in retaliation. By 2 May 1945 a local truce had been declared to allow food conveys through to the Dutch citizens. On the evening of 4 May 1945, the regiment received word that the cessation of hostilities would occur on the following day and subsequently, a double issue of rum was authorized within the regiment to all personnel. After VE Day on 8 May 1945, the regiment moved towards Hippo and eventually to Doorn. The last day of the regiment’s official existence was 30 June 1945.

56th Heavy Regiment, Royal Artillery, from March 1945.

(IWM Photo, NA 22470)

British 155-mm Long Tom gun, Italy February 1945. This gun fired a 127-pound shell to a range of 13.2 miles (21.2 km).

In early 1945 Operation Goldflake began to transfer selected British and Canadian forces from the Italian Front to reinforce 21st Army Group for its final offensive into Germany. 56th Heavy Regt was one of the units transferred in an operation that involved a sea voyage to Marseilles and then an overland journey to Belgium. This was not completed until after the crossing of the Rhine in late March, and the units saw little action in the final stages of the campaign.

When the war in Europe ended on VE Day, 56th Heavy Regt was in The Netherlands with 1st Canadian Army Group Royal Artillery (AGRA). 6th Heavy Regiment RA came under command 1st Canadian Army Group RCA on 23 Apr 45 at 1500 hours. By now it had adopted the new standard organization of two batteries of 4 x 7.2-inch howitzers and two of 4 x 155mm guns (the US-made ‘Long Tom’). On 7 May the regiment parked its guns at Arnhem aerodrome and returned its ammunition to the supply column. The personnel were then moved through liberated towns to Beverwijk in North Holland, where they established a concentration area for surrendered German troops and equipment. The regiment also took over the coastal defences from their German garrisons. The regiment served in British Army of the Rhine after the war ended, until it was disbanded between 16 and 27 March 1946.

(IWM Photo, B 9956)

7.2-inch howitzer 51st Heavy Regiment, Royal Artillery, France, 2 September 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3378347)

Gunners of “X” Battery, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), digging a breech pit for a captured 155mm. gun to be used to fire on Dunkirk. Adinkerke, Belgium, 15 September 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3559551)

Major R.E. Lucy and Lieutenant E.G. Pethybridge of “X” Battery, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), laying the battery’s guns on zero line before opening fire on Dunkerque. Adinkerke, Belgium, 15 September 1944.

107th AA Brigade

16th AA Operations Room, RCA

2nd Heavy AA Regiment, RCA

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3607609)

Ordnance QF 3.7-inch Heavy AA Gun manned by 2nd Canadian Heavy AA Regiment.

109th Heavy AA Regiment, RA

1st Canadian Centaur Battery, RCAA

At the beginning of August 1944, the left (coastal) flank of First Canadian Army was held by the British 6th Airborne Division (of which, 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion was a part), whose divisional artillery consisted of one airlanding light field regiment (53rd (Worcestershire Yeomanry) Airlanding Light Regiment, Royal Artillery) equipped with 24x 75-millimetre pack howitzers. To supplement this artillery firepower, 1st British Corps had on 21 June 1944 formed an ad hoc battery of 12x 95-millimetre Centaur self-propelled equipments, which was designated “X” Armoured Battery, Royal Artillery (“X” Armd Bty, RA). These 12x 95-millimetre Centaur self-propelled equipments, had formerly been operated by the Royal Marines Armoured Support Group[,elements of which had landed on 6 June 1944, in support of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division to provide supplementary artillery support, and had continued to support various Canadian and British units until it was decided, due to their losses (in both personnel and equipment) from enemy action, accidents and mechanical breakdowns, to withdraw the Royal Marines Armoured Support Group from Normandy.

These 95-millimetre Centaur self-propelled AFVs, were based on the British designed and built Cruiser Tank, Mark VIII, Centaur (A27L). Only 80 of these close support versions of the tank, mounting a 95-millimetre howitzer in the turret, in place of the standard armament of a 6-pounder gun were produced, and were simply known, as the ‘Centaur IV.’ The crew consisted of a commander, gunner, loader, driver, and co-driver. Fully loaded, the Centaur IV weighed 28 tonnes, and was 6.4 metres in length, by 2.5 metres in height, by 2.9 metres wide. The Centaur IV was armed with a 95-millimetre tank howitzer (Ordnance Quick Firing) and a co-axial 7.92-millimetre BESA machine gun, both of which were mounted, side by side, in the turret. The turret could be traversed manually by hand, or by a hydraulic power system, which enabled the turret to be completely traversed in14-15 seconds at the highest speed. The 95-millimetre tank howitzer had an elevation of minus 5-degrees to plus 34-degrees, and a nominal maximum range of 5,486 metres, and used fixed ammunition, in the form of either a high explosive (HE) shell, or high explosive hollow charge (HES) (capable of penetrating either armour, or concrete) shell, each weighing 11- kilograms, or a 7-kilogram smoke shell. There was stowage within the vehicle for 51 rounds of 95-millimetre ammunition (28 HE, five HES, and 18 Smoke), and for 4,950 rounds of 7.92-millimetre ammunition, contained in 22 boxes (with each box containing one 225-round belt). Like all other British tanks of the period, the Centaur IV had a 51-millimetre smoke bomb thrower (for localized smoke protection) mounted in the turret roof, with stowage inside the tank for 24 bombs, and was also equipped with a No. 19 wireless set (radio), which was housed in the turret. The No. 19 wireless set included an “A” set for general use, a “B” set for short range inter-tank work at troop level, and an intercommunication unit for the crew, so arranged that each member could establish contact with any one of the others. There was also an armoured box attached to the rear hull plate, which contained an “Infantry Telephone,” by which targets could be indicated to the crew commander from those being supported.

By August 1944, it had become necessary for the British to withdraw these reinforcement personnel from the ad hoc “X” Armd Bty, RA, to be employed as Royal Artillery reinforcements elsewhere, and they informed First Canadian Army, that they could no longer maintain this supplementary battery to the 6th Airborne Divisional Artillery, and that they would be withdrawing their personnel as of 8 August 1944. Since it was felt that the continued existence of this ad hoc battery was of an operational necessity at this time to provide artillery support within the 6th Airborne Divisional area of operations, Staff Duties, General Staff Branch, Headquarters First Canadian Army, on 4 August, drew up a request for the approval of Lieutenant-General H.D.G. Crerar, General Officer Commanding-in-Chief First Canadian Army, for the authorization to form a temporary Canadian unit to man the 12x 95-millimetre Centaur self-propelled equipments of the battery. This request was duly authorized by Crerar, on 6 August 1944, with a note that the continued authorization of this temporary Canadian unit, was to be reviewed monthly.

Details of the organization of this proposed unit were attached to the Staff Duties request of 4 August, as Appendix “A,” under the heading of “Temporary SP Bty RCA (95mm CENTAUR),” under which, the proposed title of the unit was given as “1 Centaur Bty RCA,” with the proposed personnel strength of the unit given as 11 officers, and 100 other ranks, and that the 12x 95-millimetre Centaur self-propelled equipments, and ammunition were already available. It also went on to state that administrative personnel and vehicles were not included in the proposed War Establishment, as the administration of the proposed unit was to be entirely undertaken by the British 6th Airborne Division, and that the formation of the unit would be made under the arrangements of First Canadian Army, with effect from 6 August 1944, and that the unit was to operate under the command of 1st British Corps. Lastly, it was stated that the unit would be disbanded as soon as its present operational necessity ceased (which was forecasted as within three to four weeks).

With Crerar’s authorization of 6 August for the formation of 1 Centaur Battery, RCA, things followed along quickly. Under Canadian Section General Headquarters 1st Echelon, 21 Army Group Administrative Order No. 5, dated 7 August 1944, the authorization for the formation of Serial CM 804, 1st Canadian Centaur Battery, RCA, with effect from 6 August 1944, in the North-Western European Theatre of Operations, under instructions of Headquarters First Canadian Army, and the approved Table of Organization for the battery was published. This was followed on 8 August by a letter from the Canadian Section General Headquarters 1st Echelon, 21 Army Group, to Canadian Military Headquarters (London), with an attached copy of the approved Table of Organization, informing them that the General Officer Commanding-in-Chief First Canadian Army (Crerar), had authorized the formation of Serial CM 804, 1st Canadian Centaur Battery, RCA, with effect from 6 August 1944. Subsequently, and after having received Privy Council authorization from National Defence Headquarters (Ottawa), the formation of Serial CM 804, 1st Canadian Centaur Battery, RCA, with effect from 6 August 1944, was notified under Canadian Military Headquarters Administrative Order No. 139, dated 18 August 1944.

Under the Table of Organization that was published under both Cdn Sec GHQ 1 Ech 21 A Gp Admin Order No. 5/44, and CMHQ Admin Order No. 139/44, 1st Canadian Centaur Battery, RCA, was to consist of 11 officers, and 103 other ranks, organized into a Battery Headquarters (two officers, and ten other ranks), and three Troops, with each Troop consisting of a Troop Headquarters (three officers, and 11 other ranks), and two Sections (each of ten other ranks), for a total Troop strength of 34 all ranks. Each Troop was to be equipped with one motorcycle, one Car 5-cwt (a Jeep), one Truck 15-cwt (fitted for Wireless (Radio)), one Observation Post Tank, and four (two per Section) 95-millimetre Centaur self-propelled equipments, for a total battery strength of 12x 95-millimetre Centaur IVs.

On 9 August 1944, Captain F.D. Miller (Royal Canadian Artillery) arrived at “X” Armoured Battery, Royal Artillery, 6th Airborne Division, to begin the process of the handover of the battery to 1st Canadian Centaur Battery, RCA, and found that it was going to be necessary to keep the 95-millimetre Centaur IVs in action during the handover of the battery’s equipment from British to Canadian hands. The next day, Captain Miller met the incoming Battery Commander, Major D.M. Cooper (Royal Canadian Artillery), and a draft of Royal Canadian Artillery personnel, who were drawn from No. 12 Canadian Base Reinforcement Battalion (No. 2 Canadian Base Reinforcement Group), consisting of six Lieutenants, six Sergeants, and three other ranks. After meeting with the Brigadier, Royal Artillery, Headquarters First Canadian Army, from where three 15-cwt trucks were obtained, Major Cooper, Captain Miller, and the nine-member draft proceeded to join “X” Armd Bty, RA. Upon arriving in the battery area, Major Cooper, assigned two Lieutenants, and two Sergeants, to each of 1st Canadian Centaur Battery’s three Troops, and appointed Captain Miller “C” Troop Leader, following which, Major Cooper met with Major Marchand (Royal Artillery), the Battery Commander, “X” Armoured Battery, RA. Marchand informed Cooper, that his battery was nothing more then predicted shooting on counter mortar, counter bombardment, and harassing fire tasks, and that the current policy of Headquarters 6th Airborne Divisional Artillery, because the position of the division was static, was maximum harassing fire on the enemy’s administrative areas, and vigorous and immediate retaliatory fire, to that of the enemy.

From 11 to 14 August, the men of 1st Canadian Centaur Battery, learned their respective jobs, and duties from their British counterparts of “X” Armoured Battery, and familiarized themselves with the 95-millimetre Centaur IVs. The battery’s Gunners were also greatly aided by three Instructors in Gunnery who were rushed over to Normandy from No. 1 Canadian School of Artillery (Overseas) in the United Kingdom to help the gunners in mastering the workings of the 95-millimetre tank howitzer. Also, during this period, another 22 personnel of the Royal Canadian Artillery, were brought forward to the battery from No. 12 Canadian Base Reinforcement Battalion, and the three Troops of the battery were organized with one Sherman Observation Post Tank, four (two per Section) 95-millimetre Centaur IVs, and one Truck 15-cwt. On 14 August, another 38 personnel of the Royal Canadian Artillery, arrived from No. 12 Canadian Base Reinforcement Battalion, and as of 8:00 P.M., that evening, Canadian personnel took over completely from their British counterparts. This was followed by the next day being spent in fine tuning the organization of 1st Canadian Centaur Battery, and also saw the establishment of Battery Headquarters, in rear of “A” Troops position, and the move of Major Cooper up to the battery position from Headquarters 6th Airborne Divisional Artillery. Captain E.J. Leapard (Royal Artillery), who had served with “X” Armoured Battery, RA, since its formation, was attached to 1st Canadian Centaur Battery, and was appointed Battery Captain. Also, 15 members of the British Royal Corps of Signals, and one mechanic (gun) from the British Corps of Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, who had served with “X” Armoured Battery, RA, were attached to 1st Canadian Centaur Battery, fulling the earlier stated commitment of the British in undertaking the administrative needs of the battery. 16 August saw the withdrawal of the remaining Royal Artillery members of “X” Armoured Battery, RA, and the arrival of Captain W.A. Walker, and Captain J. Else (both Royal Canadian Artillery), who respectively, were appointed “A” Troop Leader, and “B” Troop Leader. At 11:00 P.M. that evening, 1st Canadian Centaur Battery was warned to be prepared to move the next morning, as 6th Airborne Division began their advance toward the mouth of the River Seine along the coast, as part of First Canadian Army’s push to the River Seine, with 1st British Corps on the left, and 2nd Canadian Corps on the right.

On 17 August 1944, under command of Headquarters 53rd (Worcestershire Yeomanry) Airlanding Light Regiment, Royal Artillery, 1st Canadian Centaur Battery came into action near Troarn, France, in support of the British 6th Airlanding Brigade. From 17 to 27 August, the battery continued in support of elements of the 6th Airborne Division, which included 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, and Dutch infantrymen of the Royal Netherlands Brigade (Princess Irene’s), and of elements of the British 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division, as 1st British Corps continued their advance toward the River Seine. By the morning of 27 August, the battery had only one Sherman Observation Post Tank, three 95-millimetre Centaur IVs, and one 95-millimetre Cromwell VI left in action due to enemy action, accidents and mechanical breakdowns, which had occurred along the way since first going into action on 17 August, and had taken up gun positions to the rear of Toutainville, France. During the afternoon of 27 August, the 15 members of the British Royal Corps of Signals, who had been attached to the battery, were released and sent back to British 31 Reinforcement Holding Unit, and the battery’s tank crews who had accompanied their broken down, or damaged Sherman Observation Post Tanks, and 95-millimetre Centaur IVs, to workshops, rejoined the battery, leaving only the individual drivers behind.

Earlier, on 24 August, while 1st Canadian Centaur Battery was out of action in a concentration area pending deployment for an attack beyond Pont-l’Évêque, France, the Brigadier Royal Artillery, Headquarters First Canadian Army, and the Officer Commanding, 53rd (Worcestershire Yeomanry) Airlanding Light Regiment, Royal Artillery, met with the Battery Commander, Major D.M. Cooper. During this meeting they suggested to Major Cooper that he endeavour to operate the battery as a six-gun battery, instead of that of a 12-gun battery, due to the battery’s losses (in both personnel and equipment) from enemy action, accidents and mechanical breakdowns, and that the battery would probably only be in operation for another two weeks, with the pending withdrawal of the 6th Airborne Division from 1st British Corps. Major Cooper was also informed at this time, that the 15 members of the British Royal Corps of Signals, were to be withdrawn from their attachment to the battery on 27 August (as noted in the paragraph above).

From their gun positions to the rear of Toutainville, France, 1st Canadian Centaur Battery remained in action until 12:00 P.M., 28 August 1944, at which point they ceased fire for the last time. During the afternoon, the battery moved back to a concentration area, and the reorganization from a 12-gun, to a six-gun battery took place. This reorganization lead to the release of Captain Walker, Captain Miller, two Lieutenants, and the gun crews (24 other ranks) of six 95-millimetre Centaur IVs (less drivers), who were all sent back to No. 2 Canadian Base Reinforcement Group, as Royal Canadian Artillery reinforcements. On 29 August, Major Cooper, Captain Leapard (Royal Artillery), and Captain Else, went to Headquarters Army Troops Area First Canadian Army, where Major Cooper received authority to disband 1st Canadian Centaur Battery, Royal Canadian Artillery, with effect from 30 August 1944, and also instructions on the disposal of the battery’s guns, vehicles, equipment, and personnel.

On 30 August, 1st Canadian Centaur Battery moved to a concentration area near Pont-l’Évêque, France, where the process of the disposal of the battery’s guns, vehicles, equipment, and personnel began on the morning of 31 August. Between 31 August – 2 September 1944, the battery’s vehicles, and equipment were returned to the applicable Canadian Army Vehicle Park, or Ordnance Stores. The battery personnel themselves, were dispatched to No. 13 Canadian Base Reinforcement Battalion (No. 2 Canadian Base Reinforcement Group), as Royal Canadian Artillery reinforcements.

Having learned of the planned withdrawal of the 6th Airborne Division from 1st British Corps with effect from 30 August, Staff Duties, General Staff Branch, Headquarters First Canadian Army, drew up a request (dated 29 August 1944) for the approval of Lieutenant-General H.D.G. Crerar, General Officer Commanding-in-Chief First Canadian Army, for the authorization to disband Serial CM 802, 1st Canadian Centaur Battery, RCA, with effect from 30 August 1944, which was duly authorized by Crerar. Notification of the authorized disbandment of Serial CM 802, 1st Canadian Centaur Battery, RCA, under instructions of Headquarters First Canadian Army, was published under Canadian Section General Headquarters 1st Echelon, 21 Army Group Administrative Order No. 10, dated 9 September 1944. This was followed by a message from Canadian Section General Headquarters 1st Echelon, 21 Army Group, to Canadian Military Headquarters (London), with an attached copy of the submission authorizing the disbandment of 1st Canadian Centaur Battery, RCA (signed by Crerar), and a copy of Cdn Sec GHQ 1 Ech 21 A Gp Admin Order No. 10/44, under which it was notified. Subsequently, the disbandment of Serial CM 804, 1st Canadian Centaur Battery, RCA, with effect from 30 August 1944, was notified under Canadian Military Headquarters Administrative Order No. 149, dated 13 September 1944.

Of the three Sherman Observation Post Tanks, and 12x 95-millimetre Centaur IVs, that 1st Canadian Centaur Battery had originally taken over from “X” Armoured Battery, Royal Artillery, only one Sherman Observation Post Tank (Census No. T149788), and four 95-millimetre Centaur IVs (Census Numbers T185007, T185107, T185373, and T185387) were in serviceable and operational condition when turned into 259 Delivery Squadron, Royal Armoured Corps (the ‘Corps’ delivery squadron for 1st British Corps), on 4 September 1944. These five vehicles were duly turned over to “F” Squadron, 25th Canadian Armoured Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment), Canadian Armoured Corps (the ‘Army’ delivery squadron for First Canadian Army), on 5 September 1944, from where they were returned to the applicable Ordnance facility. The remaining two Sherman Observation Post Tanks, and eight 95-millimetre Centaur IVs, having been struck-off-charge of 1st Canadian Centaur Battery, were in various workshops throughout the 1st British Corps area, undergoing repairs, of one sort or another. (Mark W. Tonner, MilArt)

(IWM Photo, B5457)

Centaur IV tank with 95mm howitzer of ‘H’ Troop, 2nd Battery, Royal Marine Armoured Support Group, 13 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4233764)

A British close-support Centaur 95-mm howitzer self-propelled gun used to support the Royal Marines serving alongside Canadians during the amphibious invasion of Normandy, June 1944

19th Canadian Army Field Regiment

On 5 July 1943, the 19th Field received orders to move overseas. They left Halifax on 21 July on board the RMS Queen Elizabeth and arrived in Greenock 27 July 1943 and fell under the command of the II Canadian Corps. On 19 October 1943, the 19th Field was briefly transferred to the command of the 5th Canadian Armoured Division before once again being transferred to the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division when the 5th was moved to the Italian Campaign. Between July 1943 and May 1944, the 19th Field would begin training for the coming invasion of mainland Europe and exchanged their Sextons for American M7 Priests, which were self-propelled 25-pounders, similar to the Sexton that had an armament of 105mm and could fire a distance of 11,500 yards.

While in England, the 19th took part in several training operations, but specifically “Exercise Savvy”. It was the first divisional training exercise the regiment took part in, which focused on the firing of artillery on ships towards coastal targets and landing on beaches under fire. While in England, the 19th Field was also inspected by General Bernard Montgomery on 28 February 1944, and King George VI on 25 April 1944, in the prelude to the invasion of Europe.

On 23 May 1944, the 19th Field’s camp was sealed for security reasons and plans were finalized for Operation Overlord: the long-awaited invasion of German occupied France. The final preparations were made as all vehicles were waterproofed and ammunition was brought up. On 1 June 1944, the 19th Field moved to its marshalling areas in Gosport and Southampton before embarking on the longest day. On 3 June 1944, Forward Observation Officers (FOOs) went to their respective units with the North Shore Regiment as Landing Craft were prepared to be filled with infantry units.

D-Day: 6 June 1944

The Canadian assault on Juno Beach had three infantry brigades – the 7th, 8th and 9th – of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division with the 7th landing at Courseulles-sur-Mer, the 8th at Bernieres-sur-Mer and St. Aubin-sur-Mer with the 9th landing after the initial assault passing through the 8th’s sector and advancing on Authie and Carpiquet airfield before capturing the high ground above Caen. The 19th was attached to the 8th brigade and the 12th, 13th, and 14th Field Regiments were also involved bringing a total of 96 M7 Priest guns into action.[9] Specifically, the 19th was part of the 14th Canadian Field Regiment Artillery Group led by Lt.-Col. H.S. Griffin with each regiment firing towards the beaches from four Landing Craft towards their target of Nan Red beach.

The Landing Craft carrying the 19th and the other three Field Regiments advanced at about 6:30 a.m. with the 22nd and 30th LCT Flotilla carrying the 24 M7 Priests of the 19th. At 7:39 a.m., Major Peene the Fire Control Officer, gave the order to commence firing when they were 9,000 yards out. The guns of the 19th were the first Canadian to go into action and began firing towards northern France to signal the imminent invasion of German occupied Europe. Each gun launched 100 to 150 rounds over the course of about 30 minutes further saturating the German held territory. One gun from each of the six troops were firing phosphorus shells with seven fires being started on the Nan Red beach. The commander of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, General Rod Keller, said the SP’s “put on the best shoot they ever did.” The Field Regiments had their M7 Priests strapped to the deck of the landing craft and went in firing towards the beaches as planes and naval vessels pounded the beaches. After they reached a 2,000 yards from shore they turned around and passed the inbound North Shore Regiment infantry of the first wave. Once the beachhead had been secured they came around again and landed with the second wave of infantry to provide close artillery support against any German counterattack.

Artillery is often a feared weapon of war, but studies conducted by the 21st Army Group’s 2nd Operational Research Section found the gunners were highly inaccurate thanks to the intense waves of the English Channel. The report said the 19th missed their targets by up to 1,000 yards since they were sent on the wrong course inland by the navy. Once it was corrected, the inaccuracy prevailed with the unpredictable English Channel wreaking havoc on the sights of the gunners. They were still about 700 yards wide and 300 yards deep from their intended target.[14] Also causing difficulty was that the concrete fortifications were between three and seven feet in thickness.

At 9:10 a.m. ‘D’ Troop of the 63rd Battery landed west of St. Aubin-sur-Mer under mortar and rifle fire on Nan Red beach and within 10 minutes they had their first gun 200 yards inland and in action providing fire support. ‘C’ Troop followed shortly after with ‘E’ and ‘F’ Troop also landing and in action by 10 a.m. with the 55th Battery and Q Battery being delayed due to a rudder being damaged and massive traffic trying to land on the beaches.

Shortly after landing, the 19th took their first casualties of the war with Lt. Malcolm, the regimental survey officer, being wounded and Gunner B.T. McHughen being killed. A further two men were killed and 17 more wounded on the first day. The regiment had a vehicle damaged when a M7 Priest of ‘E’ Troop hitting a mine and a track was blown off with it taking two hours to repair. The 55th Battery also faced its first difficulty when an ammunition explosion had two M7 Priests and a Bren Carrier catch fire quickly spreading to other vehicles and threatening to become larger as it moved towards live ammunition. Gunner H.R. Chaplin, already wounded from shrapnel, jumped in the Bren Carrier that had the ammunition and moved it safety to prevent further casualties or damage. Chaplin received the Military Medal for this act.

They ran into the German 716th Infantry Division that was primarily used as an occupation division and primarily made up of Polish, Russians, Ukrainians and other nationalities from the Soviet Union who were pressed into service. They had mostly obsolete Czechoslovakian equipment from the late-1930s, but also had a small cadre of non-commissioned officers that had combat experience on the Eastern Front giving the green troops veteran leadership.

The 19th ended D-Day in positions just outside St. Aubin-sur-Mer with them being called for close fire support multiple times throughout the day as German tanks and infantry counterattacked the positions gained by Canadian infantry. With night falling over northern France and the Allied beachhead secured the 19th had three soldiers killed and another 18 wounded in the first 24 hours of Operation Overlord. (Wikipedia)

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3231470)

Company Sergeant-Major W.H. Galloway and Captain H.J. “Bummer” Stirling of the 19th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), Normandy, France, 22 June 1944.

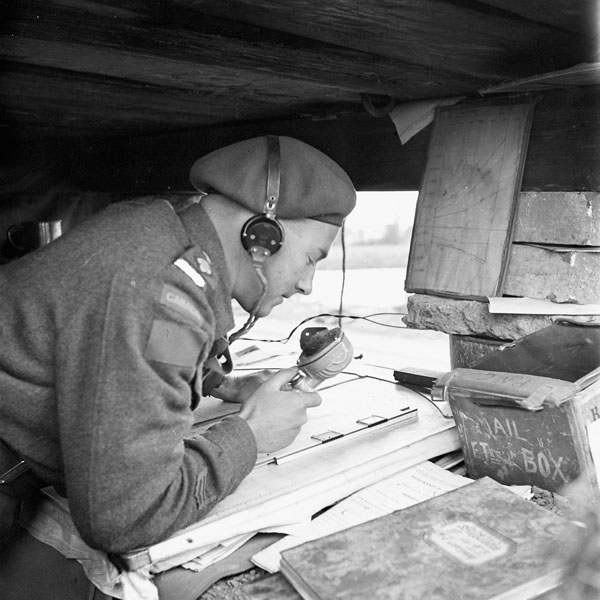

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3208741)

Sgt. R.A. Garbutt of the 19th Field Regiment, RCA, showing shrapnel holes made in the radiator of his CMP C8A Heavy Utility, Computor truck by a German anti-tank gun, possibly from a high-explosive (HE) round such as a 7.5-cm or 10.5-cm gun, 16 June 1944. The truck has covers over the side openings. A Heavy Utility, Computor (HUC) was used by Artillery Surveyors as a Command Post (CP) to do the computations from the surveyor’s raw data.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3231477)

Sergeant V.R. Francis, 19th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), displaying a German 88-mm Panzerschreck anti-tank rocket launcher, discovered at a captured German radar station, France, 16 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396110)

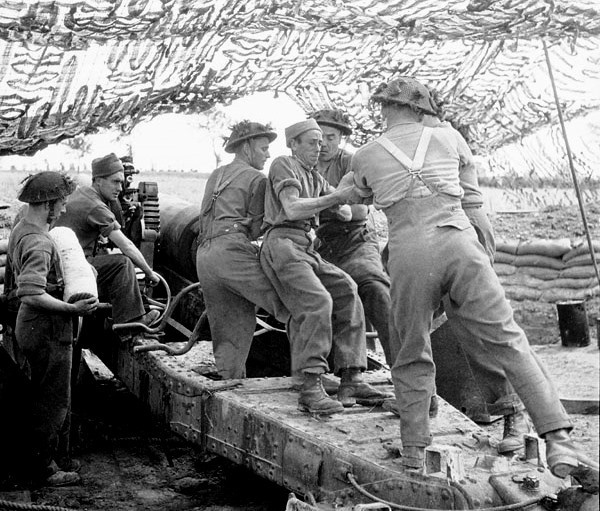

Gun crew with the Priest M-7 self-propelled gun A3 “The Wacky Seven” of the 19th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), France, July 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396109)

Bombardier B.W. Bailey in a Priest self-propelled gun of the 19th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), France, July 1944.

The Canadian assault on Juno Beach had three infantry brigades – the 7th, 8th and 9th – of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division with the 7th landing at Courseulles-sur-Mer, the 8th at Bernieres-sur-Mer and St. Aubin-sur-Mer with the 9th landing after the initial assault passing through the 8th’s sector and advancing on Authie and Carpiquet airfield before capturing the high ground above Caen. The 19th was attached to the 8th brigade and the 12th, 13th, and 14th Field Regiments were also involved bringing a total of 96 M7 Priest guns into action. Specifically, the 19th was part of the 14th Canadian Field Regiment Artillery Group led by Lt.-Col. H.S. Griffin with each regiment firing towards the beaches from four Landing Craft towards their target of Nan Red beach.

The Landing Craft carrying the 19th and the other three Field Regiments advanced at about 6:30 a.m. with the 22nd and 30th LCT Flotilla carrying the 24 M7 Priests of the 19th. At 7:39 a.m., Major Peene the Fire Control Officer, gave the order to commence firing when they were 9,000 yards out. The guns of the 19th were the first Canadian to go into action and began firing towards northern France to signal the imminent invasion of German occupied Europe. Each gun launched 100 to 150 rounds over the course of about 30 minutes further saturating the German held territory. One gun from each of the six troops were firing phosphorus shells with seven fires being started on the Nan Red beach. The commander of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, General Rod Keller, said the SP’s “put on the best shoot they ever did.” The Field Regiments had their M7 Priests strapped to the deck of the landing craft and went in firing towards the beaches as planes and naval vessels pounded the beaches. After they reached a 2,000 yards from shore they turned around and passed the inbound North Shore Regiment infantry of the first wave. Once the beachhead had been secured they came around again and landed with the second wave of infantry to provide close artillery support against any German counterattack.

Artillery is often a feared weapon of war, but studies conducted by the 21st Army Group’s 2nd Operational Research Section found the gunners were highly inaccurate thanks to the intense waves of the English Channel. The report said the 19th missed their targets by up to 1,000 yards since they were sent on the wrong course inland by the navy. Once it was corrected, the inaccuracy prevailed with the unpredictable English Channel wreaking havoc on the sights of the gunners. They were still about 700 yards wide and 300 yards deep from their intended target. Also causing difficulty was that the concrete fortifications were between three and seven feet in thickness.

At 9:10 a.m. ‘D’ Troop of the 63rd Battery landed west of St. Aubin-sur-Mer under mortar and rifle fire on Nan Red beach and within 10 minutes they had their first gun 200 yards inland and in action providing fire support. ‘C’ Troop followed shortly after with ‘E’ and ‘F’ Troop also landing and in action by 10 a.m. with the 55th Battery and Q Battery being delayed due to a rudder being damaged and massive traffic trying to land on the beaches.

Shortly after landing, the 19th took their first casualties of the war with Lt. Malcolm, the regimental survey officer, being wounded and Gunner B.T. McHughen being killed. A further two men were killed and 17 more wounded on the first day. The regiment had its vehicle damaged when a M7 Priest of ‘E’ Troop hitting a mine and a track was blown off with it taking two hours to repair. The 55th Battery also faced its first difficulty when an ammunition explosion had two M7 Priests and a Bren Carrier catch fire quickly spreading to other vehicles and threatening to become larger as it moved towards live ammunition. Gunner H.R. Chaplin, already wounded from shrapnel, jumped in the Bren Carrier that had the ammunition and moved it safety to prevent further casualties or damage. Chaplin received the Military Medal for this act.

They ran into the German 716th Infantry Division that was primarily used as an occupation division and primarily made up of Polish, Russians, Ukrainians and other nationalities from the Soviet Union who were pressed into service. They had mostly obsolete Czechoslovakian equipment from the late-1930s, but also had a small cadre of non-commissioned officers that had combat experience on the Eastern Front giving the green troops veteran leadership.

The 19th ended D-Day in positions just outside St. Aubin-sur-Mer with them being called for close fire support multiple times throughout the day as German tanks and infantry counterattacked the positions gained by Canadian infantry. With night falling over northern France and the Allied beachhead secured the 19th had three soldiers killed and another 18 wounded in the first 24 hours of Operation Overlord.

3rd Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

The regiment was equipped with the 5.5-inch medium gun/howitzer, later converting to the 4.5-inch Gun (Canadian Specification). In March 1942, the 3rd Medium was assigned to I Canadian Corps in England; in July 1944, the unit was transferred to II Canadian Corps for service in Northwest Europe. It was later assigned to the First Canadian Army level of command under 2 Army Group RCA (2nd AGRCA). The 3rd Medium Regiment, RCA, was disbanded on November 16, 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 5053591)

Gunners of the 3rd Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), preparing to fire a 5.5-inch gun, 26 November 1943.

4th Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

7th Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, PA-169331)

7th Medium Regiment, 12th Battery, “A” Troop, fire on Germans with 5.5 inch guns, Bretteville-Le-Rabet, Normandy, 16 August 1944.

The 7th Medium crossed the Channel in the second week in July 1944, and from then until the end of the fighting in the first week of May 1945 it took part in all the major battles and actions in which First Canadian Army was engaged: Normandy, the Seine crossing, the Channel ports (Boulogne and Calais), the Scheldt, Bergen op Zoom, Nijmegen salient, the Rhineland, the Rhine crossing, the advance through central and northern Netherlands, and finally across the Ems River into northwest Germany.

The 7th Medium fired its first round in anger at Rots, near Caen, Normandy, shortly after 18:00 on 13 July 1944, and its last, also shortly after 18:00, from its last gun position at Veenheusen in Germany, a short distance from Emden, on 4 May 1945. In the course of 10 months in action, the 7th occupied about 60 gun positions, fired nearly 70,000 rounds of 100-pound shells in support of three Canadian divisions, most of the British divisions and the 1st Polish Armoured Division, all of the British 21st Army Group.

The major battles in which the 7th was engaged were of course Normandy, the Scheldt and the Rhineland. The fire program for the opening of the latter is reported to have been the largest in the West during the war: at 05:00 on 8 February 1945, 1,400 British and Canadian guns of all calibres opened fire at once in support of the British XXX Corps, consisting for the opening of the battle of four British divisions and the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division attacking east from Nijmegen into Germany. Included in the preliminary bombardment, which ended at 09:30, were 16 medium regiments (13 Royal Artillery and three Royal Canadian Artillery. This was followed at 10:00 by the 2½-hour barrage in support of XXX Corps infantry attacking into Germany. In the ten months in which the 7th Medium was in action it had 124 casualties, of which 35 were killed and 89 wounded (some of the latter returned to the unit on recovery).

In Normandy, during Operation Totalize, on August 8, 1944, a group of American bombers dropped their ordnance right on top of the 7th medium regiment, 12th battery, Royal Canadian Artillery. “The great problem on our side was road space, and it was while waiting in our gun positions, still firing at the retreating German forces, that the first disaster of the campaign befell us. A flight of American Fortresses flying high over 12th Battery area unloaded their bomb load right on top of the battery and on a nearby ammunition depot. B troop received most of the damage and Lt. J.E. Clark and ten other ranks were killed or died of wounds shortly afterwards. Captain W.G. Ferguson and eighteen other ranks were wounded and evacuated”.

Several G.P.O.s from the 7th became ‘Air Observation Post’ pilots with No. 665 Squadron RCAF, and No. 666 Squadron RCAF: Lt. A.B. Culver, Lt. R.G. Everett, and Lt. R.A.S. Perley. The 7th Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, was disbanded on 8 June 1945.

10th Medium Regiment, Royal Artillery

The Royal Artillery 9 AGRA became the 21st Army Group AGRA in the NW Europe Campaign on its embarkation to France on 12 July 1944. On landing in Normandy, the regiment was placed under the command of 5 AGRA, which was the British 30 Corps AGRA. On 14 August 1944, the regiment was returned to 9 AGRA, with whom it fought its way through France, Belgium and Holland until 1 December 1944, when it was transferred to the 2nd Canadian AGRA as the replacement for the 15th Medium Regiment RA, which had been chosen to be converted back to Infantry. The 10th Medium Regiment supported the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, 2nd Canadian Corps, throughout the campaign to take the Dutch, Long Left Flank of Holland in 1945 to The North Sea. Crossing the Rhine at Emmerich, the regiment supported the 2nd Canadian Corps until the end of the war in May 1945, when it was transferred back to 5 AGRA, 30 Corps. The Regiment was disbanded at Winsen, Germany on 15 April 1946.

15th Medium Regiment, Royal Artillery (disbanded after supporting the Canadians, in December 1944).

1st Heavy Regiment, Royal Artillery (supported Canadians).

2nd Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment (Mobile)

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3607609)

Ordnance QF 3.7-inch Heavy AA Gun manned by 2nd Canadian Heavy AA Regiment.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3211345)

Gunners of the 2nd Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, pushing an Ordnance QF 3.7-inch Heavy h (9.84 cm) anti-aircraft gun through mud, 1 February 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3250940)

Gunners of the 2nd Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (R.C.A.), carrying a battery charge, Dunkirk, France, 1 February 1945.

1st Rocket Battery, RCA

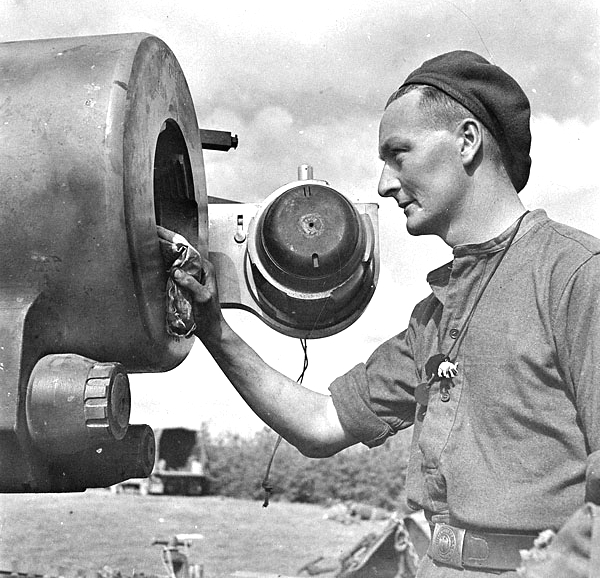

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3601142)

Gunner R. Foulkes of the 1st Rocket Battery, Royal Canadian Artillery (R.C.A.), is holding the connecting wire which fires one of the rockets of the Landmattress rocket launcher during firing trials near Helchteren, Belgium, 29 October 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3601147)

Sergeant V.D. Miller of the 1st Rocket Battery, Royal Canadian Artillery (R.C.A.), holds three different sizes of spoilers used to regulate the speed of rockets fired from the Landmattress rocket launcher during firing trials near Helchteren, Belgium, 29 October 1944

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3204964)

Personnel of the 1st Rocket Battery, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), loading a Landmattress rocket launcher, Helchteren, Belgium, 29 October 1944.

1st Radar Battery, RCA

In January 1942 No. 1 Canadian Radio Location Unit (1 CFLU) was authorized. On 22 March 1942, 4 Officers and 224 ORs arrived in England from Canada and on 23 March 1942 were taken on strength at 1 Canadian Artillery Reinforcement Unit. The No. 1 CRLU served with British Anti-Aircraft Regiments on the South coast of England until the summer of 1943, when orders were received to disband. Personnel not serving with the British at this time were transferred to other Regiments and/or retrained. One hundred and seventy-five personnel still serving with the British on the South coast of England, on 27 September, 1944,received orders to form a Radar (radio detection and ranging) Battery with their mission being to detect enemy mortar fire. The Unit proceeded to France for immediate training. While in North West Europe the Radar Battery served with all the advancing fronts. The radar units picked up enemy mortar bomb signals and relayed this information to the Artillery, which would attempt to silence the enemy mortars. This they did through Belgium, Holland and into Germany until the war ended officially on 8 May 1945.

1st Canadian Infantry Division

1st Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Horse Artillery

2nd Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

3rd Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

1st Anti-Tank Regiment

2nd Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment

2nd Canadian Infantry Division

4th Field Regiment

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3222766)

A Universal Carrier of the 4th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), Vaucelles, France, 18 or 20 July 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3209327)

Lieutenant L.W. Spurr directing the fire of the 25-pounder guns of the 4th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), near Antwerp, Belgium, 30 September 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3202160)

Gunner O.R. Weisner and Sergeant S.C. Mitchell, 4th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), washing their clothes, Ossendrecht, Netherlands, 23 October 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3202163)

Gunner E.G Westover, 4th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), Ossendrecht, Netherlands, 23 October 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3202165)

Sergeant E.F. Offord, 4th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), piling empty shell cartridges, Ossendrecht, Netherlands, 23 October 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3202162)

Gunner D. Hendry, 4th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (R.C.A.), checking cordite which has been sitting in the rain for a number of days, Ossendrecht, Netherlands, 23 October 1944.

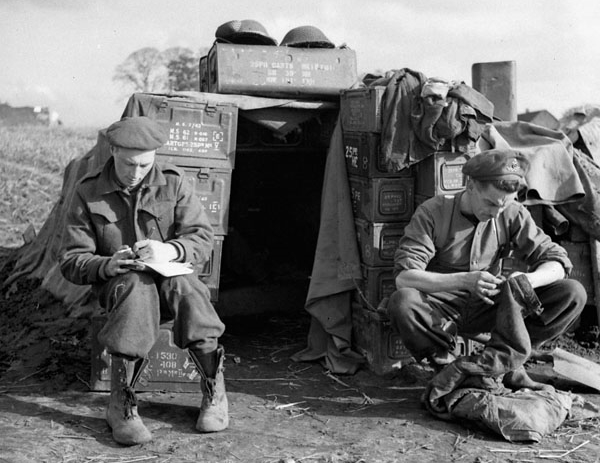

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3202168)

Bombardiers J.H. Wilson and G.M. Hart, 4th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (R.C.A.), writing and sewing in front of their house, which is made of sand-filled ammunition boxes, Ossendrecht, Netherlands, 23 October 1944.

5th Field Regiment

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3192317)

Gunners of “B” Troop, 5th Battery, 5th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, firing a 25-pounder gun, 1 February 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3224152)

Captain Ronald Leathen of the 5th Field Regiment giving “Fire” order on the phone, 1-2 February 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3224151)

Lieutenant Malcolm Taylor (left) and Major Dick Walkem of 5th Field Regiment looking over the intelligence map, 1-2 February 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3240700)

Personnel of the 5th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), with one of the regiment’s 25-pounder guns, Malden, Netherlands, 1 February 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3224160)

Officers of the 5th Field Regiment in the underground cook house – Gunner Art McCullough (left) and Gunner Bill Roy preparing lunch, 1-2 February 1945.

6th Field Regiment

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3227262)

Lieutenant Aaron Churchill of 6th Field Regiment, RCA, in a Sherman tank in Normandy talking on his wireless set, 16-17 August 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3250965)

Gunner M. Lupton of the 6th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), cleaning the breach of a French 155mm coastal gun which had been used by a German coastal artillery unit north of Nieuport, Belgium, 13 September 1944.

2nd Anti-Tank Regiment

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3202240)

Despatch rider Frank Shaughnessy of the 2nd Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), Ju;ly 1943.

(IWM Photo, B 14435)

An Archer 17-pdr self-propelled gun near Nutterden, 9 February 1945. The Archer was a variant of the Valentine tank armed with a 17-pounder gun. The vehicle was unique in having a rear-facing main armament, allowing the vehicle to be driven directly out of a firing position. The vehicle was small, but cramped (the driver had to vacate his seat when the gun was in operation lest he be seriously injured by the gun’s recoil). The first production models were issued in Mar 1944, and a total of 665 were built. The gun had 11° of traverse, 15° of elevation and 7½° of depression. The vehicle had stowage for 39 rounds of ammunition. Armour ranged from 60-80mm and the vehicle had a crew of 4.

(IWM Photo, B 14529)

Archer 17-pdr self-propelled gun in the flooded streets of Kranenburg, 11 February 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3563575)

Archers of the 2nd Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, taking part in a parade marking the handing-in of the guns of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division near Oldenburg, Germany, 15 May 1945.

3rd Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3230704)

Lance-Bombardier R.G. Laidman and Gunner D. Rodgers of the 3rd Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), playing cribbage near Antwerp, Belgium, 30 September 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3216429)

Lieutenant Ken Guy of the 3rd Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (R.C.A), taking part in Operation SPRING, Fleury-sur-Orne, France, 25 July 1944.

3rd Canadian Infantry Division

12th Field Regiment

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3526089)

Gunners of the 12th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (R.C.A.), with the Victory issue of the Maple Leaf newspaper, Aurich, Germany, 20 May 1945.

13th Field Regiment

14th Field Regiment

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3191596)

H.M. King George VI inspecting ‘Priest’ SP guns of the 12th, 13th or 14th Field Regiments, RCA, in England, 25 April 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396094)

Gunner C.F. Bolderstone in a Priest M-7 self-propelled gun of the 14th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), France, 20 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3205227)

Gunners with a Priest M-7 105-mm. self-propelled howitzer of 34 Battery, 14th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), France, 20 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3231482)

Gunners J.R. Robinson and L.T. Groves, both of 34 Battery, 14th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), stacking 105mm. shells in Normandy, France, 20 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3526098)

Bombardier L.A. Boyle, 34 Battery, 14th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), inserting a cartridge in a 105-mm. shell, France, 20 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396099)

Personnel of the 34th Battery, 14th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA) with a ‘Priest’ self-propelled gun, France, 20 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3202991)

Sergeant D. Mills and Gunner H.W. Embree checking the gunsight of a Priest M-7 105mm. self-propelled gun of the 14th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), France, 20 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3526084)

Gunners of 34 Battery, 14th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (R.C.A.), taking part in Exercise MANNER II near Salisbury, England, 20 April 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3526089)

Lieutenant John MacIsaac (left), 14th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (R.C.A.), discussing D-Day fire plan tactics with Bombardier Charles Zerowel aboard a Landing Ship Tank, Southampton, England, 4 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3230157)

Gunners of the 81st Battery, 14th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (R.C.A.), on the Ems River south of Emden, Germany, 26 April 1945.

3rd Anti-Tank Regiment

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3208270)

Canadian tank crews removing water-proofing from their M10 Tank Destroyers, with a Centaur forward and off to the right, on the Normandy beachhead, 6 June 1944. The metalwork items at the bottom of the image are deep wading ducts that were fitted to Shermans and other tanks to allow them to get ashore. (Philip Moor). These were 3inch M10s of the 3rd Canadian Anti-Tank Regiment. They did land on Juno but some were in support of the Royal Marines as they moved East to connect with the British forces on Sword beach. The Marines did have their own Centaur armored vehicles but the M10s seem to have been tasked as anti-tank support. (Ron Volstad). The 17 pounder modification for the M10 was not yet available in sufficient numbers so the RCA anti-tank units made do with the US mounted gun. (Benjamin Moogk)

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3520748)

Infantrymen of Le Régiment de la Chaudière riding on an M-10 A1 tank destroyer vehicle of the 3rd Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (R.C.A.) during the attack on Elbeuf, France, 26 August 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3203098)

A Universal Carrier towing a six-pounder anti-tank gun of the 3rd Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), Gouy, France, 30 August 1944.

4th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment

4th Canadian (Armoured) Division

15th Field Regiment

23rd Field Regiment (Self-Propelled)

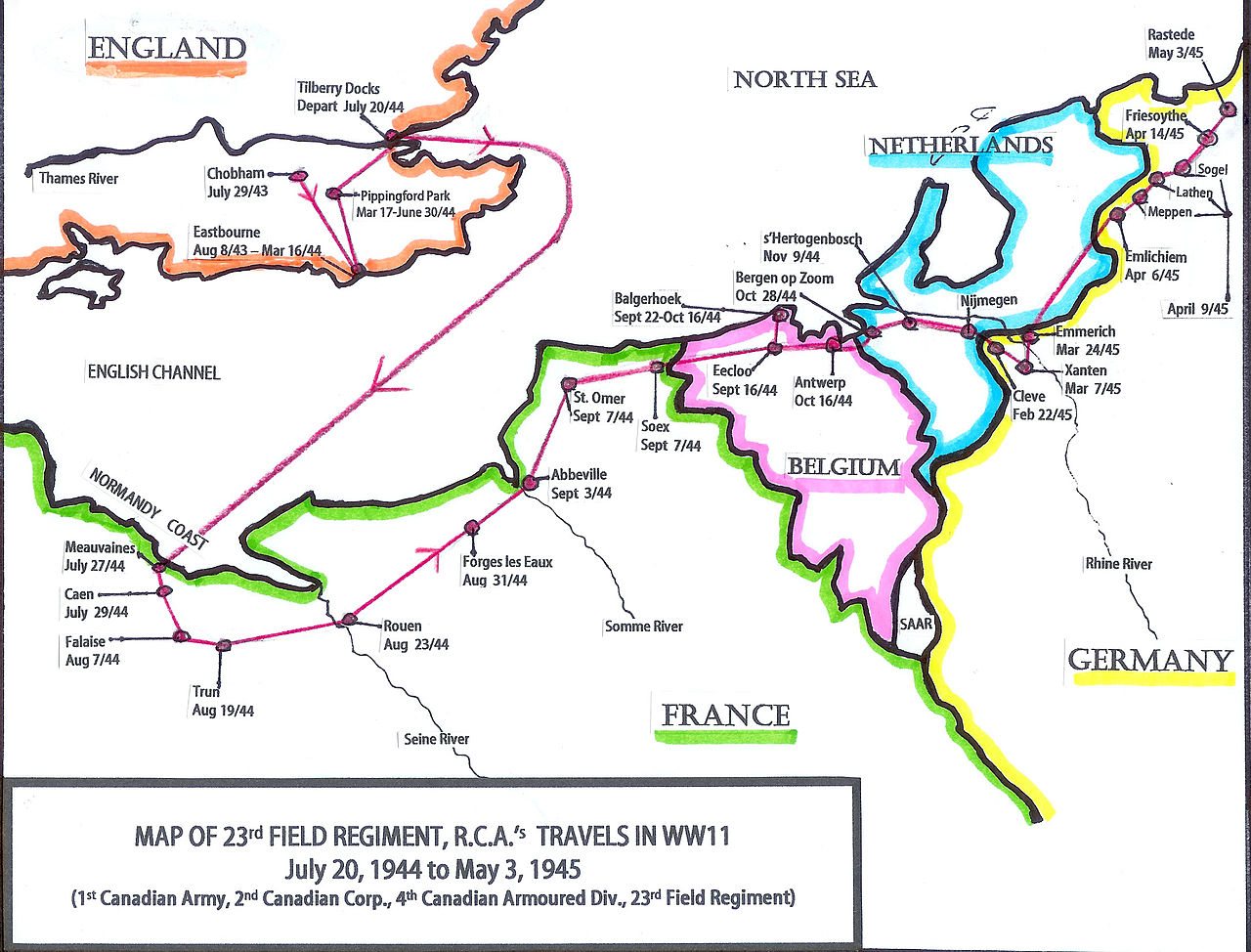

Formed in Canada in 1942, the regiment consisted of three batteries that were recruited mainly from Ontario. After a period of training in Canada the unit deployed to the United Kingdom in July 1943. The month after D-Day, the regiment landed in France and subsequently participated in the breakout campaign from Normandy into Belgium and the Netherlands, before seeing their final actions of the war in Germany.

The regiment participated in the breakout campaign, on the “Green Up – Maple Leaf Up” route from Normandy, France, into Belgium and the Netherlands, and they ended action in Germany.

The three batteries that made up the 23rd Field Regiment were:

“The 31st”, which had formed part of the 7th (Toronto) Field Regiment (Reserve) mostly from Toronto, Ontario. Its company name was “Peter” and the troops’ initials were A (Abel) and B (Baker).

“The 36th”, which was from the areas of Cobourg, Port Hope, and Peterborough, Ontario. Its company name was “Queen” & the troops’ initials were C (Charlie) & D (Dog).

“The 83rd”, from the 8th Field Brigade (Reserve) from the areas of Hamilton, Brantford, and St. Catharines, Ontario. Its company name was “Roger” and the troops’ initials were E (Easy) and F (Fox).

26 July 1944 – Disembarked at Arromanches and moved inland to Banville area, near Caen.

July to September 1944 – activity in areas of Meauvaines, south of Caen near Ifs, Mondeville, Four, Soliers, Grentheville, LaHogue, Tilly, Operation Totalize (the breakout from Caen perimeter and push down Route Nationale 158 to Falaise), Hill 180, 195 and 206 – south of Bretteville-le-Rabet, Saint-André-sur-Orne and south of Ifs, Verrières, Gausmesnil, Roquancourt, Caillouet, River Laize, Bretteville-le-Rabet, Hautmesnil, St. Aignon de Cramesnil, Renemesnil, Operation Tallulah — then changed to Operation Tractable (intention of smashing through the anti-tank screen between Quesnay Woods and Potigny along the River Laison, crossing the river and striking on to Falaise, at the same time seizing crossing of the Rivers Ante and Dives), River Laison at Rouvres, Olendon, Perrières, Le Moutiers-en-Auge, Le Menil Girard (north-east of Trun), 31st battery – River La Vie and River Touques, Rouen, Coudehard, Monnai, Bernay, (liberated) Bout de la Ville, St. Pierre les Elbeuf, River Seine, Criqueboeuf-sur-Seine just north-west of Pont de L’Arche, Ymaro, Le Hamel aux Batiers, Grainville-sur-Ry, 36th Battery to Crenon River, Boissay, 83rd Battery to Forges-les-Eaux, Orival, Airaines, Wanel, Sorel just west of the Somme, high ground overlooking Abbeville, Wisquesm just this side of St. Omer, Soex and crossing the border into Belgium on 7 September 1944.

Action in Belgium

September – October 1944 – activity in areas of Leysele, St. Riquiers, southwest of Bruges/Brugge just west of Den Daelo, Holding of the Leopold, Canal de Ghent, Moerbrugge, Oedelem, Syssele, over Leopold Canal, Cliet, Balgerhoek, Eecloo, Caprycke, Bouchante, Assenede, Sas van Gent, Philippe, north-west of Maldegem, near Balgerhoek, Eecloo, via Ghent to Antwerp, north of Schildt, Operation Suitcase, Putte, Pont Heuvel, Wildert near Roosendaal Canal and Wousche Plantage.

Action in Netherlands

October 1944 to February 1945 – activity in areas of Spillebeek, Heimolen, Bergen-op-Zoom, Halsteren, Steenbergen, Dinteloord, Willemstad, Halsteren, end of Operation Suitcase, Roosendaal, Breda, Tilburg, Vught, east of ‘s-Hertogenbosch, (31st at Nulands, 83rd at Rosmalen and 36th in between), Boxtel, 36th in Gemonde, Hedikuizen, Breda area, 36th to St. Philipsland Peninsula, Operation Trojan,(simulate crossing of the Maas), Operation Schultz (intention of getting prisoners from other side of the river), Sprang north-east of Tilburg, s’Hertogenbosch, Vught and then off to Germany on 22 February 1945.

Action in Germany and the Netherlands

February, March 1945 — activity in areas of Hau (near Cleve), Operation Blockbuster, Louisendorf, Keppeln, Uedemerbruch, The Hochwald Gap, Sonsbeck, Veen, Xanten, Winnenthal and headed back to Netherlands on 12 March 1945.

12 to 22 March 1945 – In Tilburg, in the Netherlands, for rest period.

March 1945 – return to Germany, activity in areas of Huibsberden (practically on banks of the Rhine), Operation Plunder, Emmerich and Rees near Millingen (across Rhine).

2–4 April 1945 – activity in the Netherlands in the areas between Gelselaar and Diepenheim, Twente Canal, Wegdam and north of Delden.

April, May 1945 – return to Germany, activity in areas of near Wilsum, Emmlicheim, Coevorden, Ruhle, Dortmund-Ems Canal, Meppen, north along canal to Lathen, Sogel, Werlte, Lorup, Neuvrees, Friesoythe, Kusten Canal, Edewecht, Bad Zwischenahn, Rorbeck, Rastede, & on 3 May 1945, to their last gun position of the war, midway between Rastede and Nutte.

4 May 1945 — During evening it was heard on the Regiment’s radio that all German forces in northwest Germany, Denmark and the occupied part of the Netherlands had surrendered to the 21st Army Group.

5 May 1945 — Cease fire was officially proclaimed at 8:00 am[42]

War’s end and after

7 May 1945 – VE Day – On 7 May 1945 at SHAEF headquarters in Reims, France, the Chief of Staff of the German Armed Forces High Command (OKW), General Alfred Jodl, signed the unconditional surrender documents for all German forces to the Allies.[43]

14 May 1945 – Major-General Christopher Vokes, GOC, 4th Canadian Armoured Division, addressed the Regiment at Ocholt, Germany.

8 June 1945 – “Last Parade” of armour in the Netherlands. Giving the salute during the march past was Major G.H.V. Naylor (temporary Commanding Officer) and taking the salute from the reviewing stand was Major-General Christopher Vokes.

29 June 1945 – Armoured guns turned in at Nijmegen, in a “Farewell to the Guns” ceremony.

Battle casualties

The regiment suffered the following casualties:

25 Killed

64 Wounded

6 Prisoners of War (Wikipedia)

Map of the 23rd Field Regiment’s travels during the campaign inNorth West Europe.

5th Anti-Tank Regiment

8th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3206595)

Gunners of the 8th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), Vught, Netherlands, 9 December 1944.

5th Canadian (Armoured) Division

8th Field Regiment (Self-Propelled)

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3197576)

Sexton 25-pounder self-propelled gun in North West Europe, November 1944.

4th Anti-Tank Regiment

5th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment

I Canadian Corps Troops

7th Anti-Tank Regiment

1st Survey Regiment

II Canadian Corps Troops

6th Anti-Tank Regiment

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3203401)

Private W.G. Lourie examining a German Jagdpanther 8.8cm. self-propelled gun which was put out of action by the first shot from a 17-pounder gun of the 6th Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), in the Reichswald, Germany, 16 March 1945.

2nd Survey Regiment

6th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment

2nd Anti-Tank Regiment

3rd Canadian Infantry Division

12th Field Regiment

13th Field Regiment

3rd Anti-Tank Regiment

4th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment

4th Canadian (Armoured) Division

15th Field Regiment

23rd Field Regiment (Self-Propelled)

5th Anti-Tank Regiment

8th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment

5th Canadian (Armoured) Division

17th Field Regiment

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3526655)

Gunners S.S. Lott and J.G. Spear, 17th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), overhauling a jeep motor, 11th Infantry Brigade, Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (RCEME), Groningen, Netherlands, 28 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396300)

The concrete defences of the Materborn weresubjected to the fire of the 8-inch and 240-mm guns of the 3rd Super Heavy Regiment RA located in the 1st British Corps area to the South. Shown here are 240-mm Artillery shells being unloaded for the 3rd Super Heavy Regt, RA, Haps, Netherlands, Feb 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3520587)

A 7.2-inch howitzer of a Heavy Regiment of the Royal Artillery (British Army) supporting the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade, France, 28 June 1944.

The RCA in the Second World War 1939-45

The outbreak of war found Canadian Gunners still training on the weapons that their fathers had used in 1918. The forces that were mobilized with commendable speed and efficiency when hostilities commenced would have to wait many months before they could be fully re-armed with modern equipment.