First Canadian Army in the North West Europe, Battle Honours

It can be difficult to chase down specific photographs of the Canadian units that served in the campaign in North West Europe that involved formations of the First Canadian Army during the Second World War. The campaign included Canadian participation in several major periods of action, including the Raid on Dieppe, 19 August 1942, the Battle of Normandy, from 5 June 1944 through to 25 August 1944, the battles to seize the Channel Ports in September 1944, the Battle of the Scheldt in the Netherlands in October 1944, the battles in the Nijmegen Salient from November 1944 to February 1945, the Battle of the Rhineland from February 1945 to March 1945 and the battles in the Final Phase of the war from March 1945 to May. 1945

The Battle Honour North-West Europe was granted to regiments who served in any of these major periods of action. The Battle Honour’s title is suffixed with the addition of the years of service, i.e. North-West Europe, 1944-45 for a unit engaged in combat in phases of the campaign during both 1944 and 1945. The First Special Service Force was also awarded this battle honour as the only Canadian ground unit to serve in Southern France.

The following units were awarded the Battle Honour “North-West Europe”:

“NORTH-WEST EUROPE, 1942, 1944-1945”

2nd Canadian Division

The Toronto Scottish Regiment (MG)

The Toronto Scottish Regiment (Machine Gun)

During the Second World War, the regiment initially mobilized a machine gun battalion for the 1st Canadian Infantry Division. Following a reorganization early in 1940, the battalion was reassigned to the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, where it operated as a support battalion, providing machine-gun detachments for the Operation Jubilee force at Dieppe in 1942, and then with an additional company of mortars, it operated in support of the rifle battalions of the 2nd Division in northwest Europe from July 1944 to VE Day. In April 1940, the 1st Battalion also mounted the King’s Guard at Buckingham Palace. The 2nd Battalion served in the reserve army in Canada.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3262696)

Soldiers of the Toronto Scottish Regiment in their Universal Carrier waiting to move forward, Nieuport, Belgium, 9 September 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3204241)

A German armoured car dug into the ground and used as a pillbox fortification, Nieuport, Belgium, 9 September 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524442)

Private L.P. McDonald and Lance-Corporals W. Stevens and R. Dais, all of the Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA), manning a six-pounder anti-tank gun, Nieuport, Belgium, 9 September 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3199687)

Personnel of The Toronto Scottish Regiment (M.G.) aboard a motorboat en route from Beveland to North Beveland, Netherlands, 1 November 1944.

4th Canadian Infantry Brigade

The Royal Regiment of Canada

The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry

The Essex Scottish Regiment

The Royal Regiment of Canada

The regiment mobilized the Royal Regiment of Canada, CASF (Canadian Active Service Force), for active service on 1 September 1939. It embarked for garrison duty in Iceland with “Z” Force on 10 June 1940, and on 31 October 1940 it was transferred to Great Britain. It was redesignated the 1st Battalion, the Royal Regiment of Canada, CASF, on 7 November 1940 when a 2nd Battalion was formed to provide reinforcements to the Regiment in Europe. The 1st battalion took part in the raid on Dieppe on 19 August 1942. It landed again in France on 7 July 1944, as part of the 4th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, and continued to fight in North West Europe until the end of the war. The 1st battalion was disbanded on 31 December 1945 when it amalgamated with the 2nd Battalion back home.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3209320)

Infantrymen of “D” Company, Royal Regiment of Canada, supported by a Sherman tank of the Fort Garry Horse, advance from Hatten to Dingstede, Germany, 24 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3209746)

A signalman of The Royal Regiment of Canada with a No.18 wireless set near Dingstede, Germany, 25 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3209321)

Infantrymen of “D” Company, Royal Regiment of Canada, examine equipment taken from surrendering German soldiers during the advance from Hatten to Dingstede, Germany, 24 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3299067)

Corporal W.E. Oliver, Royal Regiment of Canada, directing mortar fire, watched by Private J. Keller, driver of their Universal Carrier, France, 28 September 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3525067)

Infantrymen of The Royal Regiment of Canada resting after a long march, Blankenberghe, Belgium, 11 September 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3209320)

Infantrymen of “D” Company, Royal Regiment of Canada, supported by a Sherman tank of the Fort Garry Horse, advance from Hatten to Dingstede, Germany, 24 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3209321)

Infantrymen of “D” Company, Royal Regiment of Canada, examine equipment taken from surrendering German soldiers during the advance from Hatten to Dingstede, Germany, 24 April 1945.

(Stuart Phillips Photo)

The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry (Wentworth Regiment)

The regiment mobilized the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, CASF for active service on 1 September 1939. It was redesignated as the 1st Battalion, the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, CASF on 7 November 1940. It embarked for Britain on 22 July 1940. The battalion took part in Operation Jubilee on 19 August 1942. (General Denis Whitaker, who fought as a captain with the RHLI at Dieppe, in a 1989 interview stated, “The defeat cleared out all the dead weight. It was the best thing that ever happed to the regiment.) The RHLI returned to France on 5 July 1944 as part of the 4th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, and continued to fight in North West Europe until the end of the war. The overseas battalion was subsequently disbanded on 31 December 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3205115)

Infantrymen of The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry in General Motors C15TA armoured trucks, Krabbendijke, Netherlands, 27 October 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524891)

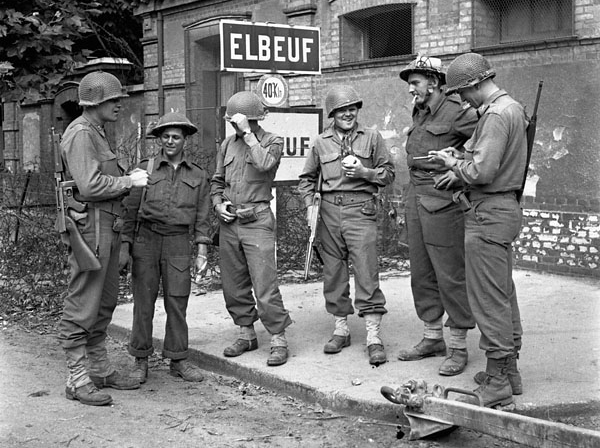

Infantrymen of The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry passing wrecked German wagons, Elbeuf, France, 27 August 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3577399)

Canadians of the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry meeting Americans of the U.S. Army’s 2nd Armoured Division, Elbeuf, France, 27 August 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3199698)

Infantrymen of The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry riding in a Universal Carrier, Krabbendijke, Netherlands, 27 October 1944.

(Stuart Phillips Photo)

The Essex Scottish Regiment

During the Second World War, the regiment was among the first Canadian units to see combat in the European theatre during the invasion of Dieppe. By the end of The Dieppe Raid, the Essex Scottish Regiment had suffered 121 fatal casualties, with many others wounded and captured. The Essex Scottish later participated in Operation Atlantic and was slaughtered attempting to take Verrières Ridge on 21 July. By the war’s end, the Essex Scottish Regiment had suffered over 550 war dead; its 2,500 casualties were the most of any unit in the Canadian army during the Second World War.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3205594)

The Essex Scottish Regiment in Universal Carriers, ready for loading onto Buffalo amphibious vehicles, 13 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3208311)

Private L. Wilkins of the Essex Regiment resting on his motorcycle, 14 April1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524539)

Lance-Corporal J.E. Cunningham of The Essex Scottish Regiment practices firing a Lifebuoy flamethrower near Xanten, Germany, 10 March 1945

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396411)

Infantrymen of The Essex Scottish Regiment lying in a ditch to avoid German sniper fire en route to Groningen, Netherlands, 14 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3224251)

Fifteen German prisoners of war captured by the Essex Scottish Regiment during the attack on Zetten and Hemmen, the Netherlands.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524165)

Captain Fred A. Tilston of The Essex Scottish Regiment near Caen, France, 5 August 1944. He was a Canadian recipient of the Victoria Cross.

On 1 March 1945, near Uedem, Germany, he led “C” Company in a 500-yard attack across muddy terrain soaked by recent rain and snow, through barbed wire and enemy automatic weapons fire. After being slightly wounded by shell fragments in the head, he personally destroyed one enemy machine gun position with a hand grenade, and led the men of C company on to a second German line of resistance when he was wounded for the second time in the hip. He struggled to his feet and led his men forward where the Essex Scottish overran the enemy positions with rifle butts, bayonets and knives in close hand-to-hand combat. While consolidating the Canadian position against German counterattacks and on his 6th trip from a neighbouring unit bringing ammunition and grenades to his company, which had been depleted to about 25% of its usual strength or 40 men, Tilston was wounded for the 3rd time in the leg. He was found almost unconscious in a shell hole and refused medical attention while he organized his men for defence against German counter-attacks, emphasized the necessity of holding the position at all cost, and ordered his one remaining officer to take command. For conspicuous gallantry and steadfast determination in the face of battle, Tilston was awarded the Victoria Cross.

6th Canadian Infantry Brigade

The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada

The South Saskatchewan Regiment

Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal

The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada

The regiment mobilized The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, CASF for active service on 1 September 1939. It was redesignated as the 1st Battalion, The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, CASF on 7 November 1940. It embarked for Great Britain on 12 December 1940. The battalion took part in Operation Jubilee, the Dieppe Raid, on 19 August 1942. It returned to France on 7 July 1944, as part of the 6th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, and it continued to fight in North West Europe until the end of the war. The overseas battalion disbanded on 30 November 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3230012)

Universal Carriers of The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada preparing to move from Germany to the Netherlands. Leer, Germany, 11 July 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 5180146)

Pte. J.E. Kirby of The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada stands guard over a V-2 rocket motor near the Antwerp Docks, Netherlands, 15 Oct 1942.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3199694)

Scouts of The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, Camp de Brasschaet, Belgium, 9 October 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3209748)

Infantrymen of Support Company, The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, supported by a Sherman tank of The Fort Garry Horse, advancing south of Hatten, Germany, 22 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524541)

Wounded infantrymen of Support Company, The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, being helped to cover south of Kirchatten, Germany, ca. 22 April 1945.

(Stuart Phillips Photo)

The South Saskatchewan Regiment

During the Second World War, The South Saskatchewan Regiment participated in many major Canadian battles and operations, as part of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division. The South Saskatchewan Regiment fought in the Dieppe Raid of 1942, Operation Atlantic, Operation Spring, Operation Totalize, Operation Tractable, and the recapture of Dieppe in 1944. They, along with the 8th Reconnaissance Regiment liberated the Westerbork transit camp on 12 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3520709)

Infantrymen of The South Saskatchewan Regiment firing through a hedge during mopping-up operations along the Oranje Canal, Netherlands, 12 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 49358)

Regimental Aid Party of The South Saskatchewan Regiment resting on the southern bank of a canal north of Laren, Netherlands, 7 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396365)

Infantrymen of The South Saskatchewan Regiment during mopping-up operations along the Oranje Canal, 12 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3205112)

German prisoners guarded by infantrymen of The South Saskatchewan Regiment, Hoogerheide, Netherlands, 15 October 1944

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396197)

Personnel of the South Saskatchewan Regiment in captured Germany. ‘Schwimmwagen’ amphibious car of the Wehrmacht, Rocquancourt, France, 11 August 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396200)

Private G.O. Parenteau of The South Saskatchewan Regiment, Rocquancourt, France, 11 August 1944.

Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal

The regiment mobilized the Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, CASF for active service on 1 September 1939. It was redesignated as the 1st Battalion, Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, CASF on 7 November 1940. It embarked for garrison duty in Iceland with “Z” Force on 1 July 1940. On 31 October 1940 it was transferred to Great Britain. The regiment took part in OPERATION JUBILEE, the raid on Dieppe on 19 August 1942. It returned to France on 7 July 1944, as part of the 6th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, and it continued to fight in North West Europe until the end of the war. The overseas battalion was disbanded on 15 November 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3209740)

Tactical Headquarters of Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, 29 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524542)

Infantry of Les Fusiliers de Mont-Royal Regiment taking cover between two tanks during attack in the vicinity of Oldenburg, Germany, 29 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3228083)

Sherman tanks of “C” Squadron, The Fort Garry Horse, passing infantrymen of Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, Munderloh, Germany, 29 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3226042)

Infantrymen of Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal loading Sten gun magazines, Munderloh, Germany, 29 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3262650)

Infantrymen of Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal in front of a statue of Frederick the Great, Berlin, Germany, 14 July 1945.

“NORTH-WEST EUROPE, 1942, 1945”

1st Canadian Armoured Brigade

14th Canadian Armoured Regiment (The Calgary Regiment)

(Stuart Phillips Photo)

14th Armoured Regiment (The Calgary Regiment)

On 16 February 1941, the 14th Army Tank Battalion (Calgary Regiment) was mobilized at Mewata Barracks.[5] When the Canadian Armoured Corps was created, the Calgary Regiment lost its status as an infantry regiment and transferred to the new corps. A reserve regiment remained in Calgary. The regiment was composed of 400 members of the reserve battalion, drawing also from reinforcement personnel from The Seaforth Highlanders of Canada and the Edmonton Regiment. The original ‘A’ Squadron was drawn from Olds and district, ‘B’ Squadron from Stettler area, ‘C’ Squadron from Red Deer, and Headquarters from Calgary, High River, and Okotoks district. In March 1941 the regiment moved to Camp Borden, becoming part of the First Army Tank Brigade and in June 1941 sailed for Great Britain. Matilda tanks were initially used on the Salisbury Plains, but these were replaced later in the year by the first manufactured Churchills.

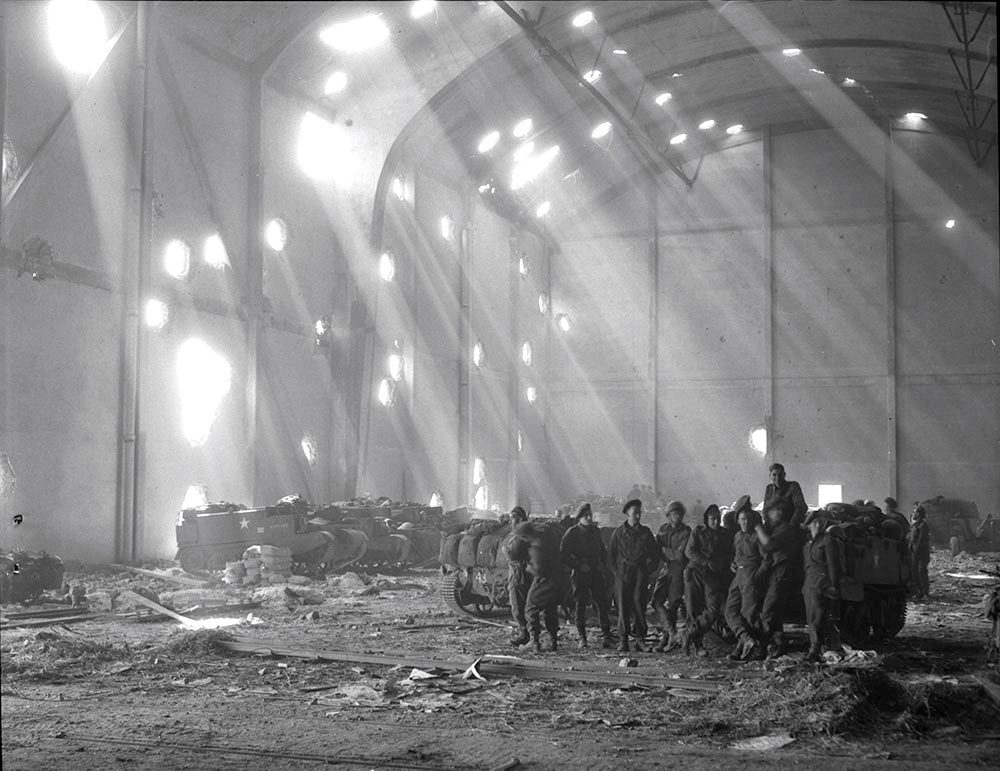

The overseas unit trained on various vehicles in Canada and the United Kingdom, and in August 1942 took the Churchill tank into battle for the first time at Dieppe. During the battle, the Battalion suffered casualties: two officers and eleven men were killed, 33 men and officers were wounded and taken prisoner with 143 other men; Only five of 181 men returned to England after the battle. A notable casualty was Lieutenant Colonel “Johnny” Andrews, who was killed in action. In the spring of 1943, Lieutenant-Colonel C.H. Neroutsos took command of the regiment. The new unit went to Sicily in 1943 with the First Canadian Army Tank Brigade, re-equipped with the Sherman tank.

In late February 1945 the regiment was moved to Leghorn and embarked to Marseilles, France, where it moved by rail to the North West Europe theatre. The regiment moved to the Reichswald Forest and on 12 April 1945 fought in the Second Battle of Arnhem, supporting the 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division to Ede, the Netherlands. The regiment’s final actions of the Second World War were in support of the 1st Belgium Brigade in clearing the resistance between the Nederrijn and Waal Rivers. When the overseas unit returned to Canada in 1945, it was disbanded, and the Calgary Regiment continued its service as a reserve armoured unit.

“NORTH-WEST EUROPE, 1944-1945”

1st Canadian Army

The Elgin Regiment

The Royal Montreal Regiment

The Lorne Scots (Peel, Dufferin and Halton Regiment

25th Armoured Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment) Canadian Armoured Corps (CAC).

Headquarters and F Squadron.

In 1942 it was designated as the 25th Armoured Regiment (The Elgin Regiment). In 1943 it became the1st Canadian Tank Delivery Regiment, laterthatsme year renamed the 25th Canadian Tank Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment). From 1943 to 1945 it served as the 25th Armoured Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment). “A” & “B” Squadrons were attached to 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade. “C” Squadron was attached to 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade. “D” Squadron was attached to 4th Canadian Armoured Division. “E” Squadron was attached to II Canadian Corps. “F” Squadron was attached to First Canadian Army. “G” Squadron was attached to 5th Canadian Armoured Division, and “H” Squadron was attached to I Canadian Corps.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No.)

A Sherman from the Canadian 25th Armoured Delivery Regiment (The Elgin Regiment) rolls down the road in France, 1944.

Canadian Infantry Corps, First Canadian Army Defence Battalion – Royal Montreal Regiment.

The regiment mobilized as The Royal Montreal Regiment (Machine Gun), CASF for active service on 1 September 1939. It was redesignated 1st Battalion, The Royal Montreal Regiment (Machine Gun), CASF on 7 November 1940. The regiment converted to armour on 25 January 1943 and was redesignated the 32nd Reconnaissance Regiment (Royal Montreal Regiment), CAC, CASF. It was reconverted back to infantry on 12 April 1944 and redesignated as the First Army Headquarters Defence Company (Royal Montreal Regiment), CASF, and on 5 April 1945 as the First Canadian Army Headquarters Defence Battalion (Royal Montreal Regiment), CASF.

The Royal Montreal Regiment (Machine Gun) embarked for the Great Britain on 7 December 1939. On 28 July 1944, the First Army Headquarters Defence Company (Royal Montreal Regiment), CASF, landed in France as a unit of First Canadian Army Troops, and it continued to serve in North West Europe until the end of the war. The overseas battalion disbanded on 30 September 1945.

On 24 May 1944, a sub-unit of the regiment, designated as the No. 9 Defence and Employment Platoon (Royal Montreal Regiment), CIC, CASF, was mobilized in England. On 27 June 1944, it landed in France as a unit of First Canadian Army Troops, and it continued to serve in North West Europe until the end of the war. This overseas platoon disbanded on 16 October 1945.

On 1 June 1945, a second Active Force component of the regiment mobilized for service in the Pacific theatre of operations as the 6th Canadian Infantry Division Reconnaissance Troop (The Royal Montreal Regiment), CAC, CASF. It was redesignated the 6th Canadian Infantry 2-2-262 Division Reconnaissance Troop (The Royal Montreal Regiment), RCAC, CASF on 2 August 1945. The troop disbanded on 1 November 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4233426)

General H.D.G. Crerar, General Officer Commanding-in-Chief First Canadian Army, in the turret of a Daimler armoured car, with Lt. Clifford Smith of the Royal Montreal Regiment.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3227968)

General H.D.G. Crerar, General Officer Commanding-in-Chief First Canadian Army, with personnel of The Royal Montreal Regiment, in front of a Daimler armoured car, Grave, Netherlands, 11 April 1945.

First Canadian Army Defence Battalion – Lorne Scots (until April 1944) replaced by the Royal Montreal Regiment.

The Lorne Scots (Peel, Dufferin and Halton Regiment) mobilized the No. 1 Infantry Base Depot, CASF, for active service on 1 September 1939. This unit was disbanded in England on 11 July 1940, following the formation of the No. 1 Canadian Base Depot on 1 May 1940 as the No. 1 Canadian General Base Depot, CASF. It was re-designated No. 1 Canadian Base Depot, CASF, the same day. It was stationed in Liverpool, England for the convenience of disembarkation and embarkation of Canadian soldiers. The depot was disbanded on 18 July 1944.

On the eve of the fall of France, the War Cabinet resolved to send every available division, including the 1st Canadian Infantry Division, to Brittany in a forlorn hope of stemming the German advance. An advance party from the Depot––Major W.H. Lent, CSM E Ching and Corporal Hiscock–went to establish a base depot at Isse near Chateaubriand. On their arrival, the expeditionary force heard of the surrender of Paris, and started to return. Major Lent’s party, who had set foot on French soil on June 12, were back in Barossa Barracks by the 18th.

The regiment subsequently mobilized the 1st Battalion, The Lorne Scots (Peel, Dufferin and Halton Regiment), CASF for active service on 6 February 1941, to “provide personnel and reinforcements for all ‘Defence and Employment’ requirements of The Canadian Army. As a result, numerous Lorne Scots defence and employment units served in the Mediterranean, North West Europe and Canada. The overseas battalion was disbanded on 21 February 1947, when its last unit, No. 1 Non- Effective Transit Depot, CASF was disbanded.

At Dieppe, No. 6 Defence Platoon (6th Canadian Infantry Brigade) were brought by LST (Landing Ship Tank), touching down on White Beach at 1605 hours on the 19th. It was split into two parts. CSM Irvine, with Privates Breault[?], Dubois, Rosenberger and Seed waded ashore with Brigadier Southern—all were reported missing. Lieutenant E.J. Norris, with Privates Hancock, Lane, Moor and Keith Spence accompanied the brigade major and signals. Their LST carried three Churchill tanks from the Calgary Regiment and a signal cart. The tanks were to lead off and clear an area to set up the headquarters. Spence was to engage enemy aircraft, but had no tracers so could not observe his fire, and ran out of ammunition since the craft carrying the stores had been hit. Most if his group were dead or wounded, and when a serviceable craft came alongside, he helped Hancock, Moore and Lane on board. As they pulled away, the LST that had brought them in sank. The Germans concentrated their fire on the craft in the water, leaving those on the shore till later, and the group pulled many soldiers of the from the water. On the return to Newhaven, the platoon commander and Privates Lane and Hancock were sent to hospital.

Corporal Larry Guator, with Privates McDougall and Stephen Prus, were to act as bodyguard for Brigadier Leth (4th Brigade). They landed on Red Beach at 0550. Prus was beside the brigadier when the latter was wounded in the arm, and carried him on a stretcher to the evacuation craft. Ashore, they fought until 1300 hours, when they were ordered to retreat.

The company was disbanded in April 1944, when its duties were taken over by the Royal Montreal Regiment.

the invasion of Sicily in July 1943, by British, Canadian and American forces; the 1st Canadian Infantry Division and the First Canadian Army Tank Brigade were part of General Montgomery’s force.

McNaughton had only committed Canadians to Sicily for battle experience, and had not planned to break up the army he had forged for the last great battle in Europe. But Ottawa had agreed, not only to leave the Canadians already there in the campaign, but to augment them with the 5th Armoured Division and First Corps Headquarters.

On 26 October 1943, the Edmund B. Alexander pulled out of Gourock with 4,700 troops, including the Headquarters I Canadian Corps and its Defence Company. The men had thought that they were going on an exercise, and as the ship joined a convoy of 24, they realised they were going into action, although even on the voyage they were unsure of their destination. It was in Sicily, at Augusta, that the Alexander disembarked, the men going ashore in landing craft. Their record in Italy is documented on a separate page.

When Italy was secured, the Canadians began in February 1945, in great secrecy, to move to Norfth West Europe. The I Canadian Corps moved to Marseille, then Antwerp, and on 15 March took over the Nijmegen area in the Netherlands.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524866)

Lieutenant J.E.R. Bingeman and a guard of honour consisting of infantrymen of The Lorne Scots (Peel, Dufferin and Halton Regiment) at a plaque unveiling ceremony outside the Hotel Der Wereld, Wageningen, Netherlands, 9 July 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524567)

An officer serving with the The Lorne Scots (Peel, Dufferin and Halton Regiment) stencilling the regiment’s identification number on a jeep, England, ca. 30 May-1 June 1943.

II Canadian Corps

12th Manitoba Dragoons

18th Armoured Car Regiment (12th Manitoba Dragoons)

During the Second World War the Regiment mobilized the 18th (Manitoba) Reconnaissance Battalion, CAC, CASF, for active service on 10 May 1941. It was redesignated the 18th (Manitoba) Armoured Car Regiment, CAC, CASF, on 26 January 1942; the 18th Armoured Car Regiment (12th Manitoba Dragoons), CAC, CASF, on 16 December 1942; and 18th Armoured Car Regiment (12th Manitoba Dragoons), RCAC, CASF on 2 August 1945. It embarked for Great Britain on 19 August 1942. On 8 and 9 July 1944 it landed in Normandy, France as a unit attached directly to II Canadian Corps, where it fought in North West Europe until the end of the war.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3202099)

General Motors T17E1 Staghound armoured cars of “A” Squadron, 12th Manitoba Dragoons, in the Hochwald, Germany, 2 March 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3224497)

General Motors T17E1 Staghound armoured cars of “A” Squadron, 12th Manitoba Dragoons, 30 December 1943.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524437)

A General Motors Staghound T-17E1 armoured car of the 12th Manitoba Dragoons crossing a Bailey bridge, Elbeuf, France, 28 August 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3191574)

General Motors T17E1 Staghound armoured cars of “A” Squadron, 12th Manitoba Dragoons, crossing the Seine River, 28 August 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3224495)

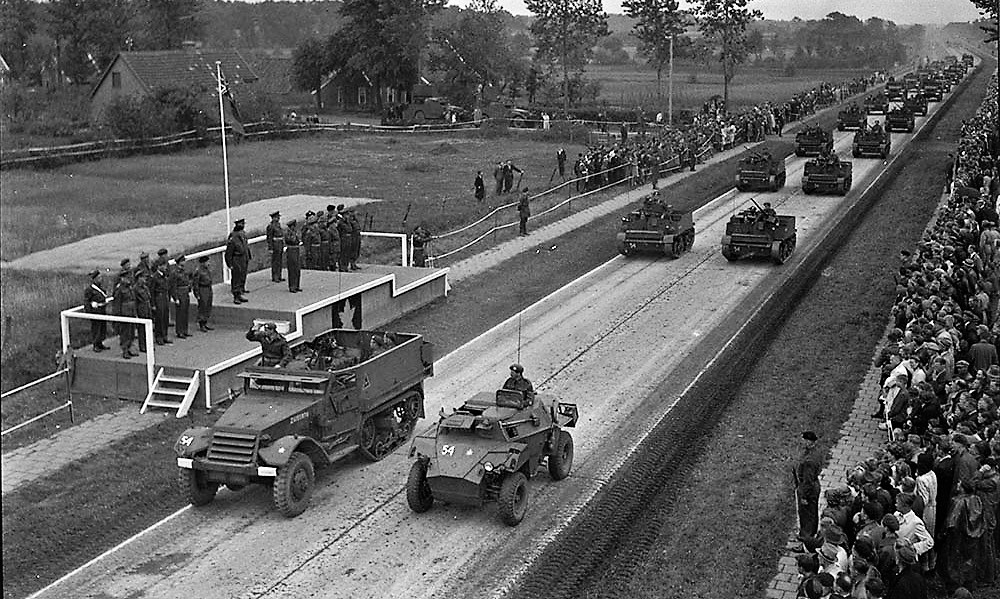

2 Canadian Infantry Division parade in front of Queen Wilhelmina. Scout cars of the12thManitoba Dragoons pass the base, 28 June 1945.

2nd Canadian Division

8th Canadian Reconnaissance Regiment (14th Canadian Hussars)

(Stuart Phillips Photo)

8th Reconnaissance Regiment (14th Canadian Hussars) (8 Recce)

8 Recce was formed at Guillemont Barracks, near Aldershot in southern England, on 11 March 1941, by merging three existing squadrons within the division. Its first commanding officer was Lieutenant Colonel Churchill C. Mann. Mann was succeeded as commanding officer on 26 September 1941, by Lieutenant Colonel P. A. Vokes, who was in turn followed on 18 February 1944, by Lieutenant Colonel M. A. Alway. The last commanding officer was Major “Butch” J. F. Merner, appointed to replace Alway a couple of months before the end of the fighting in Europe.

8 Recce spent the first three years of its existence involved in training and coastal defence duties in southern England. It was not involved in the ill-fated Dieppe Raid on 19 August 1942, and thus avoided the heavy losses suffered that day by many other units of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division. The regiment landed with its division in Normandy on 6 July 1944, one month after D-Day, and first entered combat as infantry in the ongoing Battle of Normandy. The regiment’s first three combat deaths occurred on 13 July, two of which when a shell struck a slit trench sheltering two men near Le Mesnil. Another Trooper was killed during the Battle of Caen the same day from a mortar shell.

Following the near-destruction of the German Seventh Army and Fifth Panzer Army in the Falaise Pocket in August 1944, the remaining German forces were compelled into a rapid fighting retreat out of Northern France and much of Belgium. 8 Recce provided the reconnaissance function for its division during the advance of the First Canadian Army eastward out of Normandy, up to and across the Seine River, and then along the coastal regions of northern France and Belgium. The regiment was involved in spearheading the liberation of the port cities of Dieppe and Antwerp; it was also involved in the investment of Dunkirk, which was then left under German occupation until the end of war. 8 Recce saw heavy action through to the end of the war including the costly Battle of the Scheldt, the liberation of the Netherlands and the invasion of Germany.

An early demonstration of the mobility and power of the armoured cars of 8 Recce occurred during the liberation of Orbec in Normandy. Over the period 21-23 August, the infantry of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division had succeeded in pushing eastward up to the west bank of the River Tourques, but they were unable to expand an initial bridgehead across the river because of the presence of enemy positions in Orbec on the east bank. Humbers of 8 Recce had meanwhile scouted out possible river crossings northwest of the town. They succeeded in crossing the Tourques, then circled back to Orbec and attacked the German defenders unexpectedly from the north and east. Enemy resistance in the town was rapidly overcome and the division’s advance towards the Seine could resume.

The reconnaissance role of 8 Recce often put its members well ahead of the main body of the division, especially during the pursuit of the retreating German army across northern France and Belgium in late August and September 1944. For example, elements of 8 Recce entered Dieppe on the morning of 1 September 1944, scene of the disastrous Dieppe Raid of 1942, a full 12 hours before the arrival of truck-borne Canadian infantry. The liberation of Dieppe was facilitated by the withdrawal of the German occupying forces on the previous day. The unexpectedly early liberation allowed a planned and likely devastating Allied bombing raid on the city to be called off. 8 Recce was responsible for liberating many other towns in the campaign across Northwest Europe.

During the Battle of the Scheldt, 8 Recce advanced westwards and cleared the southern bank of the West Scheldt river. In one notable action, armoured cars of ‘A’ Squadron were ferried across the river; on the other side the cars then proceeded to liberate the island of North Beveland by 2 November 1944. Bluff played an important role in this operation. The German defenders had been warned that they would be attacked by ground support aircraft on their second low-level pass if they did not surrender immediately. Shortly thereafter 450 Germans surrendered after their positions were buzzed by 18 Typhoons. Unbeknownst to the Germans, the Typhoons would not have been able to fire on their positions since the aircraft’s munitions were already committed to another operation.

Shortly after midnight on the night 6–7 February 1945 (Haps, Holland), when 11 and 12 troops of C Squadron patrolled and contacted each other and started back – 11 troop patrol was challenged with halt from, the ditch. L/Cpl. Bjarne Tangen fired a sten magazine into the area from which the challenge came and then he and the others quickly took-up positions in the ditch, while the 3rd member of their patrol ran back and collected the 12 troop patrol, together with reinforcements from 12 troop and returned to the scene of firing. The evening ended with the patrol taking one German prisoner and one deceased. The German prisoner, Lt. Gunte Finke, was interrogated and he disclosed that he gave himself up after seeing the response of an estimated 30 men from the skirmish. The German intention was to verify information that armoured cars were in the area; not to bother with foot patrol or prisoners, but to attempt to “Bazooka one of our vehicles with the 2 Panzerfaust that their patrols carried”. L/Cpl.Tangen was awarded the Dutch Bronze Cross, and Mentioned in dispatches, for this event.

On 12 April 1945, No. 7 Troop of ‘B’ Squadron liberated Camp Westerbork, a transit camp built to accommodate Jews, Romani people and other people arrested by the Nazi authorities prior to their being sent into the concentration camp system. Bedum, entered on 17 April 1945, was just one of many Dutch towns liberated by elements of 8 Recce in the final month of the war.

8 Recce’s last two major engagements were the Battle of Groningen over 13–16 April and the Battle of Oldenburg, in Germany, over 27 April to 4 May. Three members of 8 Recce were killed on 4 May, just four days before VE Day, when their armoured car was struck by a shell.

During the war 79 men were killed outright in action while serving in 8 Recce, and a further 27 men died of wounds.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524797)

8th Reconnaissance Regiment Recce vehicles of the 2 Canadian Infantry Division on barges performing an amphibious operation, from Beveland Peninsula to North Beveland Island from just north of Oostkerke, Netherlands, 1 November 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3237870)

A Universal Carrier of the 8th Reconnaissance Regiment (14th Canadian Hussars), being loaded aboard a barge en route from South Beveland to North Beveland, Netherlands, 1 November 1944.

3rd Canadian Division

7th Canadian Reconnaissance Regiment (17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars)

The Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa (MG)

7th Reconnaissance Regiment (17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars)

On May 24, 1940 the 17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars were mobilised becoming successively the 3rd Canadian Motorcycle Regiment. In February 1941 the 3rd Canadian Motorcycle Regiment became the 7th Reconnaissance Regiment (17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars) of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division (later in 1944 to be nicknamed The Water Rats) and it embarked for the United Kingdom on 23 August 1941.

The 7th Reconnaissance Regiment (17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars) landed in England on September 7, 1941. In 1941 the 6th Duke of Connaught’s Royal Canadian Hussars were called upon to furnish the Headquarters Squadron of the 5th Canadian Armoured Division and were designated 15th Armoured Regiment (6th Duke of Connaught’s Royal Canadian Hussars). In October 1943 the 5th Canadian Armoured Division landed in Italy going into action in mid-January 1944. The 15th Armoured Regiment (6th Duke of Connaught’s Royal Canadian Hussars) later moved to France in February 1945.

On June 6, 1944 the 7th Reconnaissance Regiment (17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars) participated in D-Day when members of B Squadron tasked as Beach Exit Parties and Brigade Contact Detachments landed on Juno Beach in Normandy. By July 17, 1944 the entire regiment was functioning as a Unit and continued to do so until the German surrender in 1945. The 7th Reconnaissance Regiment (17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars) campaigned through Europe winning eleven Battle Honours.

In 1945 a reconnaissance regiment was required for the occupation troops remaining in Europe. This unit was designated as the Second 7th Reconnaissance Regiment (17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars) and consisted of volunteers from several other units. The original 7th Reconnaissance Regiment (17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars) returned to Montreal. The Second 7th Reconnaissance Regiment (17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars) remained on occupation duty in Germany until relieved and sent home beginning in May 1946.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3191645)

Dutch civilians on a WASP of 7th Reconnaissance Regiment (17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars), 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, celebrating the liberation of Zwolle, Netherlands, 14 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3378681)

Personnel of the 17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars in their Humber Mk. IV armoured car in Normandy, France, 18-20 July 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3405642)

Personnel of the 17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars with the unit’s Humber IIIA armoured cars, Vaucelles, France, 18 July 1944.

The Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa (Machine Gun)

In July 1940, the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa’s active service battalion left for garrison duty in Iceland, which ended in April 1941 when they sailed to England. On 6 June 1944, the Camerons were the only Ottawa unit to land on D-Day at Juno Beach. The 1st Battalion consisted of three machine gun companies and one mortar company. Following the landing on D-Day, the battalion fought in almost every battle in the northwestern Europe campaign. However, the battalion’s soldiers were often attached as platoons and companies in support of other units, so the battalion never fought as an entire entity. During this time, the 2nd Battalion recruited and trained soldiers in Canada for overseas duty. The 3rd Battalion was formed in July 1945 as a part of the Canadian Army Occupation Force in Germany.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3238874)

Soldiers of the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa (MG), cleaning Vickers machine guns during a training exercise, England, 14 April 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3238875)

Soldiers of the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa laying down fire with a Vickers machine gun during a training exercise, England, 14 April 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3199873)

The Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa (MG) machine gunners in action firing through hedge in Normandy, 4 July 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3199857)

Personnel of the Machine Gun Platoon, Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa (M.G.), with a Universal Carrier, on the Rhine River west of Rees, Germany, 26 March 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3206448)

Members of the Regimental Aid Party of the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa (MG) treating a wounded soldier near Caen, France, 15 July 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3405375)

Lieutenant-Colonel P.C. Klaehn (centre), Commanding Officer of The Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa (MG), holding a map session with officers of the regiment near Caen, France, 15 July 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524179)

A Universal Carrier of The Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa (M.G.) passing through Holten, Netherlands, 9 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3224314)

Canada and the USA have worked together in the past to deal with war crimes issues after the battle. Here we have a soldier of the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa guarding internees at Esterwegen internment camp. U.S. Army Major A. Levine, Commanding Officer of the War Crimes Investigation Team on the Borkum Island case questions a German prisoner about the fate of seven missing American fliers, 30 October 1945.

4th Canadian Division

29th Canadian Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment (The South Alberta Regiment)

The New Brunswick Rangers

The Lake Superior Regiment (Motor)

29th Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment (The South Alberta Regiment)

The South Alberta Regiment mobilized in 1940 as part of the 4th Canadian Infantry Division. When the division was reorganized as an armoured formation to satisfy demand for a second Canadian armoured division, the South Alberta Regiment was named 29th Armoured Regiment (The South Alberta Regiment) and received Ram tanks in February 1942. The unit was again renamed as 29th Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment (The South Alberta Regiment) in January 1943.

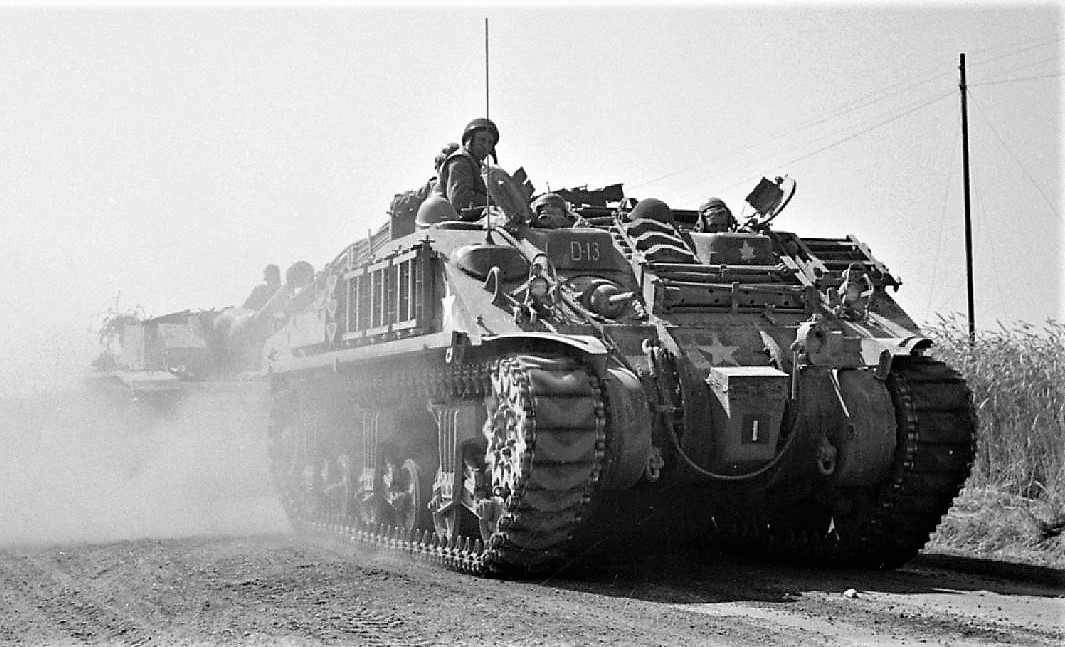

The SAR was deployed to northern France in mid-June 1944 (Normandy landings, D-Day was 6 June 1944), replacing their Ram tanks to be equipped with Stuart and Sherman tanks. They participated in the later battles of the Invasion of Normandy, taking part in Operation Totalize and finally closing the Falaise pocket in Operation Tractable. The South Albertas went on to participate in the liberation of the Netherlands and the Battle of the Scheldt.

In January 1945, they took part in the Battle for the Kapelsche Veer. They spent the last weeks of the war fighting in northern Germany

Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396233)

Major David V. Currie (left, with pistol in hand) of The South Alberta Regiment accepting the surrender of German troops at St. Lambert-sur-Dives, France, 19 August 1944. This photo captures the very moment and actions that would lead to Major Currie being awarded the Victoria Cross. Battle Group Commander Major D.V. Currie at left supervises the round up of German prisoners. Reporting to him is trooper R.J. Lowe of “C” Squadron.

Major David Vivian Currie of the SAR received the Victoria Cross for his actions near Saint-Lambert-sur-Dives, as the allies attempted to seal off the Falaise pocket. Currie was one of only 16 Canadians to receive the Victoria Cross during the Second World War. It was the only Victoria Cross awarded to a Canadian soldier during the Normandy campaign, and the only Victoria Cross ever awarded to a member of the Royal Canadian Armoured Corps. Lieutenant Donald I. Grant took a photograph of the event that would become one of the most famous images of the War. Historian C. P. Stacey called it “as close as we are ever likely to come to a photograph of a man winning the Victoria Cross.”

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3191555)

Sherman V tanks of the South Alberta Regiment (SAR) and M5A1 Stuart tanks of the 5th Canadian Armoured Division, a Ram II Observation (OP) tank with false wooden gun, Willys jeeps, Canadian Military Pattern (CMP) trucks and a Humber armoured car in the centre, laagered in the village square of Bergen-op-Zoom in the Netherlands, 31 Oct 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3228469)

Trooper J.C. McEachern hooking a cable between two Sherman tanks of The South Alberta Regiment, Louisendorf, Germany, 26 February 1945.

.

(NBMHM Collection, Author Photo)

The New Brunswick Rangers

The 1st Battalion, The New Brunswick Rangers, CASF, was mobilized on 1 January 1941. It was redesignated as The 10th Canadian Infantry Brigade Support Group (The New Brunswick Rangers), CIC, CASF on 1 November 1943 and as The 10th Independent Machine Gun Company (The New Brunswick Rangers), CIC, CASF on 24 February 1944. The unit served at Goose Bay, Labrador in a home defence role as part of Atlantic Command from June 1942 to July 1943. It embarked for Britain on 13 September 1943. On 26 July 1944, the company landed in France as part of the 10th Infantry Brigade, 4th Canadian Armoured Division, and it continued to fight in North West Europe until the end of the war. The overseas company was disbanded on 15 February 1946.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3224767)

New Brunswick Rangers on exercise, May 1943.

5th Canadian Infantry Brigade

The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada

Le Régiment de Maisonneuve

The Calgary Highlanders

(Stuart Phillips Photo)

The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada

The regiment mobilized the 1st Battalion, The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada, CASF, on 1 September 1939. This unit, which served in Newfoundland from 22 June to 11 August 1940, embarked for Great Britain on 25 August 1940. Three platoons took part in the raid on Dieppe on 19 August 1942. On 6 July 1944, the battalion landed in France as part of the 5th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, and it continued to fight in North West Europe until the end of the war. The overseas battalion was disbanded on 30 November 1945.

The 1st Battalion suffered more casualties than any other Canadian infantry battalion in Northwest Europe according to figures published in The Long Left Flank by Jeffrey Williams. On the voyage to France on the day of the Dieppe Raid, casualties were suffered by the unit during a grenade priming accident on board their ship, HMS Duke of Wellington. During the Battle of Verrières Ridge on 25 July 1944, 325 men left the start line and only 15 made it back to friendly lines, the others being killed or wounded by well-entrenched Waffen SS soldiers and tanks. On 13 October 1944 – known as Black Friday by the Black Watch – the regiment put in an assault near Hoogerheide during the Battle of the Scheldt in which all four company commanders were killed, and one company of 90 men was reduced to just four survivors.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3590885)

Infantrymen of “B” Company, The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada, firing a three-inch mortar, Groesbeek, Netherlands, 3 February 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3613491)

Soldiers with the Black Watch of Canada training with a 6-pounder anti-tank gun. Note the Lee-Enfield rifle used as a small calibre aiming device.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3203511)

Infantrymen of “C” Company, The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada, gathered around a slit trench in the woods near Holten, Netherlands, 8 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396388)

Infantry of the Black Watch of Canada (Royal Highland Regiment) crossing the river Regge south of Ommen, Netherlands, 10 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3230698)

American-born members of Support Company, The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada, South Beveland, Netherlands, 30 September 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4232588)

Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, inspecting the The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada, 1943.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3205164)

C Company commander, 5 Brigade Black Watch, Captain W.L. Barnes checks map reference with signalman Pte H. Howard, 8 April 1945.

(Stuart Phillips Photo)

Le Régiment de Maisonneuve

The regiment mobilized Le Régiment de Maisonneuve, CASF, on 1 September 1939. It embarked for Great Britain on 24 August 1940. It was redesignated as the 1st Battalion, Le Régiment de Maisonneuve, CASF, on 7 November 1940. 17 On 7 July 1944, the battalion landed in France as part of the 5th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Infantry Division. It suffered heavy casualties in the Battle of the Scheldt, and was notably depleted by the time of the Battle of Walcheren Causeway. The unit recovered during the winter and was again in action during the Rhineland fighting and the final weeks of the war, taking part in the final campaigns in northern Netherlands, the Battle of Groningen, and the final attacks on German soil. The overseas battalion was disbanded on 15 December 1945.

.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3207886)

Lieutenant Louis Woods of Le Régiment de Maisonneuve observing a German position during Operation VERITABLE near Nijmegen, Netherlands, 8 February 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524835)

Privates Arthur Richard and Aurele Nantel of the Regimental Aid Party, Le Régiment de Maisonneuve, treating a wounded soldier near the Maas River, Cuyk, Netherlands, 23 January 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3392829)

GM C15TA Armoured Truck CZ428917 ‘Aristocrat’ near Nijmegen, Netherlands, 5 December 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. )

Corporal C. Robichaud of Le Régiment de Maisonneuve examining a disabled German Sturmhaubitz 42 105-mm self-propelled gun, Woensdrecht, Netherlands, 27 October 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3210492)

A two inch mortar crew in action – Privates Raoul Archambault and Albert Harvey of Le Régiment de Maisonneuve, 23 January 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3225204)

Regiment de Maisonneuve during the attack on the Western Front, 8 Feb 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524187)

Infantrymen of Le Régiment de Maisonneuve riding on a Sherman tank of The Fort Garry Horse entering Rijssen, Netherlands, 9 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3205241)

Infantry of the Regiment de Maisonneuve moving through Holten to Rijssen, both towns in the Netherlands, 9 April 1945.

The Calgary Highlanders

The regiment mobilized for active service as The Calgary Highlanders, Canadian Active Service Force (CASF) on 1 September 1939. It was re-designated as the 1st Battalion, The Calgary Highlanders, CASF, on 7 November 1940. On 27 August 1940, it embarked for Britain. The battalion’s mortar platoon took part in the Dieppe Raid on 19 August 1942. On 6 July 1944, the battalion landed in France as part of the 5th Canadian Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, and it continued to fight in North West Europe until the end of the war. The regiment selected the Battle of Walcheren Causeway for annual commemoration after the war. The overseas battalion disbanded on 15 December 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3358102)

Corporal Frank Maguire of The Calgary Highlanders manning a machine gun in a Universal Carrier near Doetinchem, Netherlands, 1 April 1945.

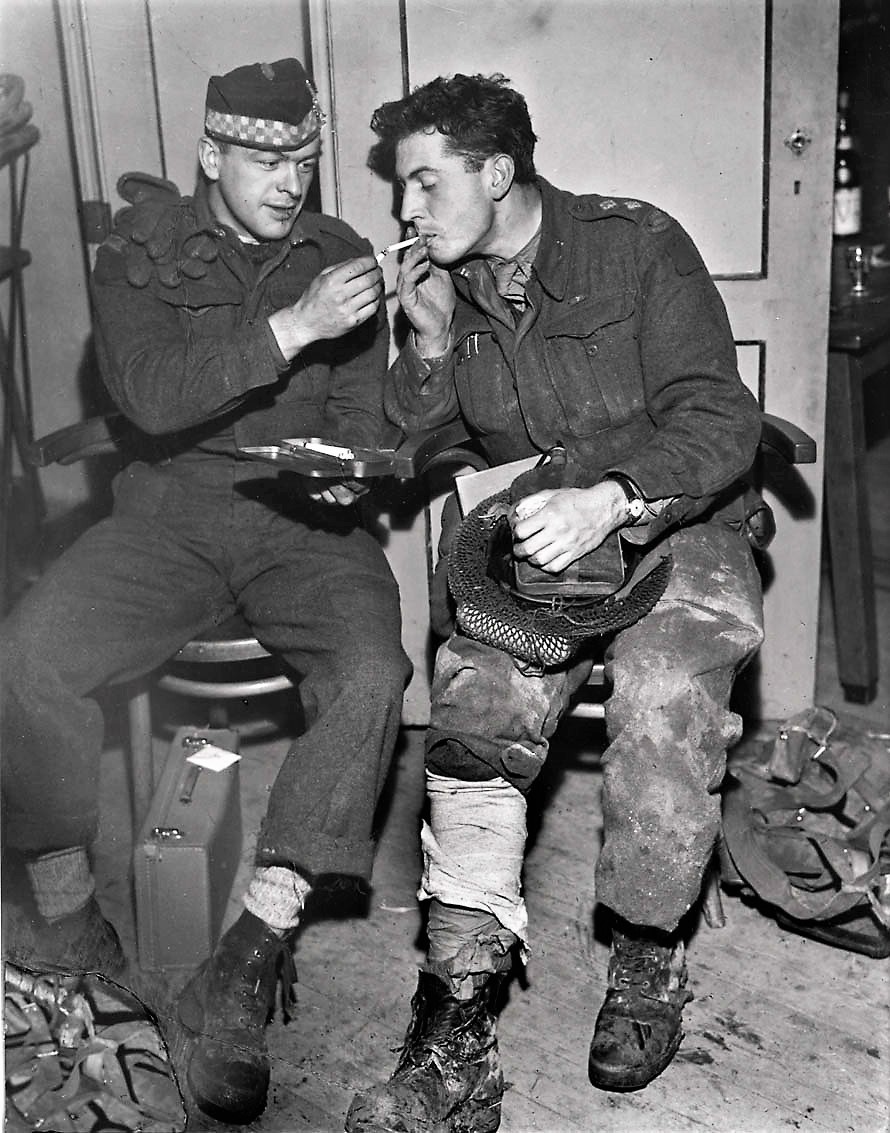

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3227193)

Private D. Tillick of the Toronto Scottish Regiment (M.G.) and Lieutenant T.L. Hoy of the Calgary Highlanders, who both were wounded on the causeway between Beveland and Walcheren, waiting for treatment at the Casualty Clearing Post of the 18th Field Ambulance, Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps (RCAMC), Netherlands, 1 November 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3405373)

Infantrymen of The Calgary Highlanders, Doetinchem, Netherlands, 1 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3358102)

Corporal Frank Maguire of The Calgary Highlanders manning a machine gun in a Universal Carrier near Doetinchem, Netherlands, 1 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3231598)

Private M. Voske and Private H. Browne of The Calgary Highlanders examinea captured German radio-controlled Goliath remote controlled demolition vehicle, Goes, Netherlands, 30 October 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3596657)

Corporal S. Kormendy and Sergeant H.A. Marshall of The Calgary Highlanders cleaning the telescopic sights of their No. 4 Mk. I(T) rifles during a scouting, stalking and sniping course, Kapellen, Belgium, 6 October 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3206370)

Sergeant Harold Marshall, of the Calgary Highlanders Scout and Sniper Platoon, posing for Army photographer Ken Bell near Fort Brasschaet, Belgium, September 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3521073)

A Calgary Highlanders soldier servicing a No. 18 wireless set, Pagham, England, 20 January 1943.

7th Canadian Infantry Brigade

The Royal Winnipeg Rifles

The Regina Rifle Regiment

The Canadian Scottish Regiment

The Royal Winnipeg Rifles

The regiment landed in England in September 1940. As part of the 7th Infantry Brigade, 3rd Canadian Division, the Rifles were in the first wave of landings on D Day, 6 June 1944. The Royal Winnipeg Rifles fought throughout the Normandy campaign, fighting in famous battles such as Caen and the Falaise Gap. After helping liberate several of the Channel Ports, the regiment fought to clear the Scheldt Estuary to allow the re-opening of the Antwerp harbour. After helping to liberate the Netherlands, the regiment ended the war preparing to assault the northern German town of Aurich. Three battalions of the regiment served during the Second World War. The 1st Battalion served in the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, the 2nd Battalion was a reserve unit that remained on part-time duty in Winnipeg, and a 3rd Battalion served in the Canadian Army Occupation Force. The 1st Battalion were among the first Allied troops to land on the Normandy beaches on D-Day. They served throughout the Northwest Europe campaign, including the Battle of the Scheldt, the Rhineland, and the final battles across the Rhine, before returning to Canada in 1945. The 3rd Battalion was raised in 1945 and remained in Germany until 1946.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3191681)

Infantrymen of The Royal Winnipeg Rifles in Landing Craft Assault (LCAs) en route to land at Courseulles-sur-Mer, France, 6 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524573)

H/Captain J.L. Steele, Chaplain of The Royal Winnipeg Rifles, talking with his driver, Rifleman J.L. Simard, France, 16 July 1944

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3227215)

Infantrymen of The Royal Winnipeg Rifles searching German prisoners, Aubigny, France, ca.16-17 August 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3513060)

Ram Kangaroo armoured troop carrier transporting personnel of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, 16 February 1945.

The Regina Rifle Regiment

The Regina Rifle Regiment, CASF, was mobilized for active service on 24 May 1940. It was redesignated the 1st Battalion, The Regina Rifle Regiment, CASF, on 7 November 1940 and embarked for Britain on 24 August 1941. On D-Day, 6 June 1944, it landed in Normandy, France as part of the 7th Infantry Brigade, 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, and it continued to fight in North West Europe until the end of the war. The 1st Battalion was disbanded on 15 January 1946.

On 1 June 1945, a third Active Force component of the regiment, the 4th Battalion, The Regina Rifle Regiment, CIC, CAOF, was mobilized for service with the Canadian Army Occupation Force in Germany. The 4th Battalion was disbanded on 4 April 1946. The 2nd (Reserve) Battalion did not mobilize. During the Second World War members of the regiment received 14 Military Medals with one bar to that award, seven Distinguished Service Orders, seven Military Cross awards, a British Empire Medal, an Africa Star, three French Croix de Guerre, and a Netherlands Bronze Lion. Many more were Mentioned in Dispatches. The regiment suffered 458 fatal casualties by 7 May 1945.

Its first taste of combat came in Normandy, landing on Juno Beach on D-Day, during which it was the first Canadian regiment to successfully secure a beachhead. It later faced the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend, which was almost completely annihilated by the British and Canadian forces. The regiment later entered Caen.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3405774)

PIAT anti-tank gunners of The Regina Rifle Regiment who knocked out a German PzKpfW V Panther tank thirty yards from Battalion Headquarters, Bretteville-l’Orgeuilleuse, France, 8 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3394461)

Infantrymen of The Regina Rifle Regiment manning a Bren gun position inside a captured German barracks, Vaucelles, France, 23 July 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3205216)

Infantrymen of The Regina Rifle Regiment and a dispatch rider firing into a damaged building, Caen, France, 10 July 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3225986)

Allied vehicles entering Caen, 10 July1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3409521)

Infantrymen of the Regina Rifle Regiment, Zyfflich, Germany, 9 February 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3256086)

A three-inch (7.62 cm) mortar crew of Support Company, The Regina Rifle Regiment, Bretteville-l’Orgueilleuse, France, ca. 9 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3582821)

Three soldiers of the Regina Rifles Regiment who landed in France on June 6, 1944, in Ghent, Belgium, November 8, 1944

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 4558334)

Lieutenant R.R. Smith briefing his Regina Rifles NCOs with a sketch of their objective, Courseulles-Sur-Mer, 4 June 1944.

(Stuart Phillips Photo)

1st Battalion The Canadian Scottish Regiment

The Canadian Scottish were unusual in 1939 in having two battalions on the strength of the Canadian Militia. The 1st Battalion was mobilized for overseas service in 1940 and trained in Debert, Nova Scotia, until August 1941, from where it moved to the United Kingdom as part of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division. On 6 June 1944 C Company was in the first wave ashore in Normandy on Juno Beach, the rest of the battalion following in the second wave. The battalion proceeded to advance a total of six miles inland – farther than any other assault brigade of the British Second Army that day. The regiment went on to earn 17 battle honours, including one for the liberation of Wagenborgen, a Dutch village; this last honour was not awarded until the 1990s.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3225491)

Captain Albert Johnson and Captain Gordon, both of the 1st Battalion, The Canadian Scottish Regiment, taking part in a house-clearing training exercise, England, 22 April 1944.

Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3191554)

H/Captain Robert Seaborn, Chaplain of the 1st Battalion, The Canadian Scottish Regiment, giving absolution to a soldier of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division near Caen, France, 15 July 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3198877)

Major C. Wightman (left) of the 1st Battalion, The Canadian Scottish Regiment, talking with Captain J.C.G. Young, a medical officer, France, 15 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3199981)

Lieutenant-Colonel D.G. Crofton, Commanding Officer of the 1st Battalion, The Canadian Scottish Regiment, examining the wreckage of a German 155mm. gun, Breskens, Netherlands, 28 October 1944.

8th Canadian Infantry Brigade

The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada

Le Régiment de la Chaudière

The North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment

(Fredericton Region Museum Collection, Author Photo)

The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada

After a build-up and training period, the unit embarked for Britain on 19 July 1941. The regiment mobilized the 3rd Battalion, The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, CASF for active service on May 12, 1942. It served in Canada in a home defence role as part of the 20th Infantry Brigade, 7th Canadian Infantry Division. The battalion was disbanded on 15 August 1943.

For the Invasion of Normandy, the regiment landed in Normandy, France, as part of the 8th Infantry Brigade, 3rd Canadian Infantry Division. The first major combat operations were on D-day 6 June 1944. The Queen’s Own Rifles landed on “Nan” sector of Juno Beach and with the support of tanks of the Fort Garry Horse captured the strategic seaside resort town of Bernières-sur-Mer. The battalion fought its way to its D-Day objective – the village of Anisy 13.5 km (8.4 mi) inland, the only Regiment to reach its assigned objective that day. The QOR had the highest casualties amongst the Canadian regiments, with 143 killed, wounded or captured. As well as losses in the initial landing, the reserve companies’ landing craft struck mines as they approached the beach.

In the battle for Caen, the QOR – as part of the 8th Infantry Brigade – participated in Operation Windsor to capture the airfield at Carpiquet which was defended by a detachment from the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend. The Germans inflicted heavy casualties and Panzer-grenadiers attempted to recapture the village.

During the war, 463 riflemen were killed in action and almost 900 were wounded as they fought through Normandy, Northern France, and into Belgium and the Netherlands, where they liberated the crucial Channel ports. Sixty more members of the regiment were killed while serving with other units in Hong Kong, Italy and northwest Europe. The overseas battalion was disbanded on 30 November 1945.

On 1 June 1945, a third Active Force battalion, designated the 4th Battalion, The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, CIC, CAOF, was mobilized for service with the Canadian Army Occupation Force in Germany. The battalion was disbanded on 14 May 1946.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3205139)

Lieutenant Stan Biggs briefing Universal Carrier flamethrower crews of The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, Vaucelles, France, 29 July 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3525803)

Officers of the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada discussing tactics, Carpiquet, France, 8 July 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3525804)

Lieutenant E.M. Peto (left), 16th Field Comapny, Royal Canadian Engineers (RCE), with Company Sergeant-Major Charlie Martin and Rifleman N.E. Lindenas, both of “A” Company, Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, planning where to lay a minefield, Bretteville-Orgueilleuse, France, 20 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3225655)

Queen’s Own Rifles demonstrate flame throwers in action against dugouts among the trees in Normandy, 29 July 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3205245)

Queen’s Own Rifles moving up to extreme front action; attack on German airport and the village of Carpiquet, 4 July 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3262647)

Infantrymen of the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, who wear full British snow camouflage kit, go on patrol near Nijmegen, Netherlands, 22 January 1945.

Le Régiment de la Chaudière

The battalion was sent to England in August 1941. The unit was assigned to the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division as a standard rifle battalion and was designated as a reserve battalion during the D-Day landings in June 1944. Le Régiment de la Chaudière came ashore on the second wave at Bernières-sur-Mer after The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, surprising the locals who hadn’t expected to find francophone troops in the liberating forces. It was the only French-Canadian regiment to participate in Operation Overlord, and one of the few French-speaking units to come ashore that day alongside the bilingual The North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment and the Free-French Commando Kieffer.

The regiment participated in the Battle for Caen, suffering several casualties in the fight at Carpiquet airfield on 4 July 1944. With the rest of the division, the regiment fought in the Battle of the Scheldt, notably in actions in the Breskens Pocket between 6 October and 3 November 1944. The unit wintered in the Nijmegen Salient and was again active in the Rhineland fighting in February 1945, and finished the war on German soil in May. A 2nd Battalion served in the Reserve Army. A 3rd Battalion was raised for the Canadian Army Occupation Force.

3rd Division’s operation to clear the Breskens Pocket was an amphibious assault by 9th Infantry Brigade from the area of Terneuzen, westward along the south shore of the Scheidt, west across the Braakman Inlet, and landing in the rear of the main German defences.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3405729)

Infantrymen of Le Régiment de la Chaudière in a Landing Craft Assault (LCA) alongside HMCS Prince David off Bernières-sur-Mer, France, 6 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3194343)

Lieutenant Jack Beveridge, who was wounded by an exploding mine, being brought aboard HMCS Prince David off Bernières-sur-Mer, France, 6 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3405729)

Infantrymen of Le Régiment de la Chaudière moving through Bernières-sur-Mer, France, 6 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 5180127)

Personnel of le Régiment de la Chaudière, Normandy, France, 8 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3520748)

Infantrymen of Le Régiment de la Chaudière riding on an M-10 A1 tank destroyer vehicle of the 3rd Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA) during the attack on Elbeuf, France, 26 August 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3203114)

Infantrymen of Le Régiment de la Chaudière talking with French civilians, Bernières-sur-Mer, France, 6 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3223932)

Infantry of the Chaudière Regiment marching German prisoners (including two civilians) back along dyke, 10 February 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3526093)

Lance-Corporal George Gagnon, Le Régiment de la Chaudière, aboard a Landing Ship Tank fusing hand grenades to be used on D-Day. Southampton, England, 4 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3942419)

Parade in Amsterdam for Queen Wilhelmina’s return by Canadian Troops and Dutch organizations. Regiment de Chaudières march past, 28 June 1945.

9th Canadian Infantry Brigade

The Highland Light Infantry of Canada

The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders

The North Nova Scotia Highlanders

(Stuart Phillips Photo)

The Highland Light Infantry of Canada

On 8 July 1944, Soldiers of the Highland Light Infantry of Canada (HLI of C), 9th Brigade, 3rd Canadian Infantry Division assaulted the German positions within the town of Buron, supported by tanks of the Sherbrooke Fusiliers and Royal Artillery. The HLI of C faced stiff opposition from members of the 25th Panzer Grenadiers of the 12th SS Panzer Div. The Battalion suffered 262 casualties, including 62 killed while liberating the town. It continued to fight in North West Europe until the end of the war. The battalion was disbanded on 1 May 1946.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3227614)

Private W. Smith of The Highland Light Infantry of Canada training to operate a Lifebuoy flamethrower, Nijmegen, Netherlands, 14 December 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3198835)

Platoon commander Lieutenant J.H. Chrystler (centre) issuing patrol instructions to Sergeant F.C. Edminston and Private L.J.L. Coté, all of The Highland Light Infantry of Canada, France, 20 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3205036)

Personnel of the Highland Light Infantry of Canada boarding LCI(L)s 252, 276 and 277 of the 1st and 2nd Canadian (260th and 262nd RN) Flotillas during Exercise ‘Fabius III’, 1 May 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3205647)

Troops of the Highland Light Infantry of Canada (Kitchener, Galt) going aboard a Canadian L.C.I.(L.) at dawn, 7 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524486)

Infantrymen of the Highland Light Infantry of Canada aboard LCI 306 of the 2nd Canadian (262nd RN) Flotilla on D-Day. The photographer standing in bows of landing craft is Lieutenant Gilbert A. Milne, 65 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3205609)

Infantrymen of The Highland Light Infantry of Canada passing Sherman tanks en route to cross the Orne River near Caen, France, 18 July 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3397598)

Infantrymen of The Highland Light Infantry of Canada attaching drag ropes to a six-pounder anti-tank gun, Thaon, France, 6 August 1944

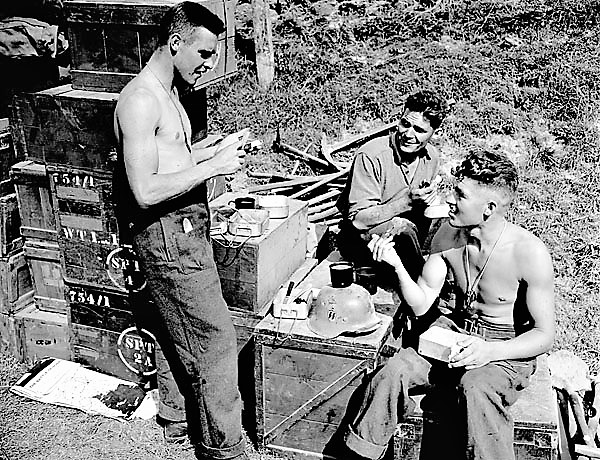

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3599865)

Privates H.A. Fraser, G.R. Wood and W.F. Sager, all of the Highland Light Infantry of Canada, eating lunch on a makeshift table, on which can be seen a German Waffen SS helmet, Thaon, France, 6 August 1944.

(Stuart Phillips Photo)

The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders (Fencibles)

The regiment mobilized The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders, CASF for active service on 24 May 1940. It was redesignated as the 1st Battalion, The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders, CASF on 7 November 1940. The unit embarked for Great Britain on 19 July 1941. On D-Day, 6 June 1944, it landed in Normandy, France, as part of the 9th Infantry Brigade, 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, and it continued to fight in North West Europe until the end of the war. The overseas battalion was disbanded on 15 January 1946. The regiment mobilized the 3rd Battalion, The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders, CIC, CAOF on 1 June 1945 for service with the Canadian Army Occupation Force in Germany. This battalion was disbanded on 24 May 1946.

The SD&G Highlanders landed in Normandy on D Day and was the first regiment to enter Caen, reaching the centre of the city at 1300 hours, 9 July 1944.

Fifty-five days later, 112 SD&G Highlanders had been killed in action and 312 more wounded in the Falaise Gap. The Regiment fought across France via Rouen, Eu, Le Hamel and Boulogne, moved into the Netherlands and took part in the amphibious landing across the Savojaardsplaat, and advanced to Knokke by way of Breskens. It moved next to Nijmegen to relieve the airborne troops, and helped guard the bridge while the Rhine crossing was prepared. The Regiment then fought through the Hochwald and north to cross the Ems-River and take the city of Leer. At dawn on 3 May 1945, German marine-units launched an attack on two forward companies of the SD&G Highlanders, occupying the village of Rorichum, near Oldersum, that was the final action during the war, VE Day found the SD&G Highlanders near Emden. It was said of the Regiment that it “never failed to take an objective; never lost a yard of ground; never lost a man taken prisoner in offensive action.”

Altogether 3,342 officers and men served overseas with the SD&G Highlanders, of whom 278 were killed and 781 wounded; 74 decorations and 25 battle honours were awarded. A total of 3,418 officers and men served in the 2nd Battalion (Reserve); of them, 1,882 went on active service and 27 were killed. A third battalion raised in July 1945 served in the occupation of Germany and was disbanded in May 1946.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3225495)

Lieutenant J. McKinnell (third from right) briefing infantrymen of The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders during a training exercise, England, 14 April 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3204914)

Infantrymen of The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders loading supplies aboard LCI(L) 252 of the 2nd Canadian (262nd RN) Flotilla during Exercise FABIUS III, Southampton, England, ca. 1 May 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3225642)

Infantrymen of the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders crossing the Orne River on a Bailey bridge built by the Royal Canadian Engineers (RCE) en route to Caen, France, 18 July 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3225644)

Infantrymen of the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders crossing the Orne River on a Bailey bridge built by the Royal Canadian Engineers (RCE) en route to Caen, France, 18 July 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3225643)

Infantrymen of the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders with a truck-mounted 40-mm Bofors anti-aircraft gun, crossing the Orne River on a Bailey bridge built by the Royal Canadian Engineers (RCE) en route to Caen, France, 18 July 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396194)

Infantryman of the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders armed with a German MP40 sub-machine gun, searching through the rubble for isolated pockets of resistance after the capture of Caen, France, 10 July 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524780)

Personnel of the Stormont Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders of Canada advancing through Bathmen, Netherlands, 9 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3524679)

Civilians waiting to be moved back from the front; members of the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders of the 9th Infantry Brigade, 3 Infantry Division are in evidence. Rhine River, Germany, 25 March 1945.

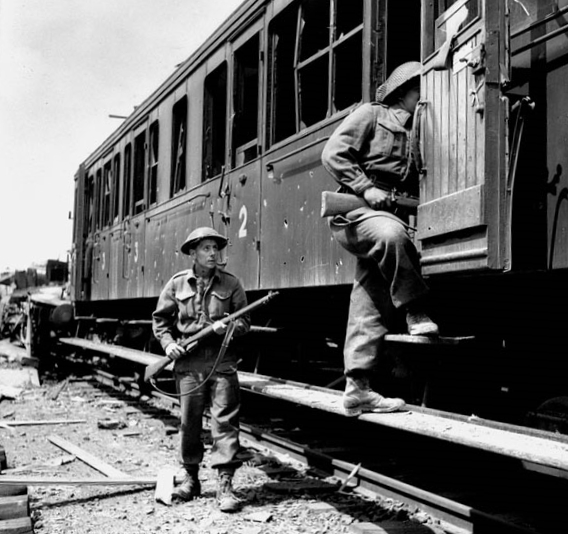

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3396132)

Infantrymen of the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders searching railway cars, Vaucelles, France, 18 July 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3521663)

Infantrymen of The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders eating lunch outside the railroad station, Caen, France, 20 July 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3194299)

Crowd welcoming Infantrymen of The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders to Leeuwarden, Netherlands, 16 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3194299)

Crowd welcoming the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders of Canada, on board a Ram Kangaroo, Leeuwarden, Netherlands, 16 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3237904)

Infantrymen of the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders aboard a Buffalo amphibious vehicle near Mehr, Germany, 11 February 1945.

(Stuart Phillips Photo)

The North Nova Scotia Highlanders

The North Nova Scotia Highlanders, CASF were mobilized for active service on 24 May 1940. The regiment embarked for England on 18 July 1941. On D-Day, 6 June 1944, the Highlanders landed in Normandy, France, as part of the 9th Infantry Brigade, 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, and continued to fight in North West Europe until the end of the war. The overseas battalion was disbanded on 15 January 1946. On 1 June 1945, the regiment mobilized the ‘3rd Battalion, The North Nova Scotia Highlanders, CIC, CAOF’ for service with the Canadian Army Occupation Force in Germany. The battalion was disbanded on 1 May 1946.

Shortly after the D-Day landings in Normandy, German soldiers under the command of Waffen SS Major General Kurt Meyer, murdered captured soldiers from the North Nova Scotia Highlanders regiment. After the war he was tried and convicted in Canada. Sentenced to death on 28 December 1945, his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment on 14 January 1946. After serving nearly nine years in prison, Meyer was released on 7 September 1954.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3191503)

The Highland Light Infantry of Canada and the North Nova Scotia Highlanders aboard LCI(L) en route to France, 6June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3205046)

Landing Craft Infantry (LCI) 135 of the 2nd Canadian (262nd RN) Flotilla carrying personnel of the North Nova Scotia Highlanders and the Highland Light Infantry of Canada en route to France on D-Day, 6 June 1944. On approaching the beach most troops closed up as far aft as possible to raise the bow to get as close aground as possible and avoid beach obstacles before lowering ramps . .a stern anchor was dropped to assist later winching off the beach. This photo of LCI 135 photo was taken sometime between 9 and 11 am when the flotilla was circling off the beaches awaiting orders to go in. The troops are “standing to” since “beaching stations” was given at 0905. At 1114, orders were given to land at Nan White. At 1129, LCI 135 touched down on Juno beach.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3614538)

French Front Line – North Nova Scotia Regiment, 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade – Furthermost Canadian outpost – ‘Arty’ O Pip sighting for a shoot, 1,000 yds from the enemy, 22 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3203205)

Major C.F. Kennedy and Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Petch of The North Nova Scotia Highlanders, France, 22 June 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3192177)

Infantrymen of the North Nova Scotia Highlanders advancing along the Orne River towards Vaucelles, France, 18 July 1944.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3209513)

The North Nova Scotia Highlanders advancing towards Zutphen. Dorterhoek, Netherlands, 8 April 1945.

10th Canadian Infantry Brigade

The Lincoln and Welland Regiment

The Algonquin Regiment

The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada (Princess Louise’s)

The Lincoln and Welland Regiment

On 16 July 1943 the 1st Battalion it embarked for Britain. On 25 July 1944 it landed in France as a part of the 10th Infantry Brigade, 4th Canadian Armoured Division, and it continued to fight in North West Europe until the end of the war. The overseas battalion was disbanded on 15 February 1946.

From Tilly-la-Campagne on 31 July 1944 until Bad Zwischenahn on 1 May 1945, the regiment distinguished itself in many actions. Over 1500 men of the regiment were casualties. Of the original men who enlisted in 1940, only three officers and 22 men were on parade in St. Catharines in 1946 when the 1st Battalion was dismissed.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3223902)

Personnel of the Lincoln and Welland Regiment with an M5A1 Stuart tank of the 4th Canadian Armoured Division awaiting orders to go through a roadblock, 11 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3224032)

Soldiers of the Lincoln and Welland Regiment advance through the streets chasing the German paratroopers out of the town, 11 April 1945.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3202801)